IT Analyst

The IT Analyst Career Path: Bridging Technology and Business Needs

An Information Technology (IT) Analyst plays a pivotal role in modern organizations, acting as a crucial bridge between technical possibilities and business objectives. At its core, the role involves analyzing an organization's IT systems, infrastructure, and processes to identify areas for improvement, solve problems, and ultimately help the business operate more efficiently and effectively through technology.

Working as an IT Analyst can be deeply engaging. You'll often find yourself dissecting complex systems, much like a detective solving a puzzle, to understand how things work and where they can be enhanced. Furthermore, the role offers the satisfaction of seeing your recommendations translate into tangible improvements, whether it's streamlining a workflow, implementing a new software solution, or enhancing cybersecurity measures, directly contributing to the organization's success.

Introduction to the IT Analyst Role

What is an IT Analyst?

An IT Analyst, sometimes referred to as a Systems Analyst or Business Systems Analyst depending on the organization's structure, is primarily concerned with understanding how technology can best serve the needs of a business. Their main objective is to evaluate current IT systems, identify requirements for new systems or modifications, and design solutions that align with strategic goals.

This involves a deep dive into existing computer systems, procedures, and organizational structures. They assess the suitability of information systems in terms of intended outcomes and liaise with end-users, software developers, and other stakeholders to achieve these outcomes. Essentially, they ensure that the technology employed is fit for purpose and delivers value.

The analyst must possess a blend of technical knowledge and business acumen. They need to understand the capabilities and limitations of technology while also grasping the operational needs and strategic direction of the business units they support. This dual focus allows them to translate business requirements into technical specifications effectively.

The Crucial Link: Bridging Technical and Business Teams

One of the most critical functions of an IT Analyst is acting as an interpreter and facilitator between technical teams (like developers, network engineers, database administrators) and business stakeholders (like department managers, end-users, executives). Miscommunication between these groups can lead to projects failing or systems not meeting user needs.

The IT Analyst translates complex technical jargon into understandable business language and converts business needs into precise technical requirements that development teams can act upon. This ensures everyone involved has a clear understanding of the project's goals, scope, and constraints.

This bridging role requires strong communication, negotiation, and interpersonal skills. Analysts must be adept at active listening to truly understand user needs and skilled at presenting technical information clearly and concisely to non-technical audiences. They often facilitate meetings, workshops, and presentations to ensure alignment.

Adapting to Change: The Evolution of the IT Analyst

The role of the IT Analyst has evolved significantly alongside rapid technological advancements. Initially focused on mainframe systems and process automation, the scope now encompasses areas like cloud computing, data analytics, cybersecurity, mobile applications, and artificial intelligence.

Modern IT Analysts must continually update their skills to keep pace with new technologies and methodologies. Agile development practices, for instance, have changed how requirements are gathered and managed, requiring analysts to be more adaptable and collaborative throughout the project lifecycle.

The increasing importance of data means analysts are often involved in data analysis, visualization, and ensuring data integrity within systems. Furthermore, with the rise of digital transformation initiatives, IT Analysts are key players in helping organizations leverage technology for competitive advantage and innovation.

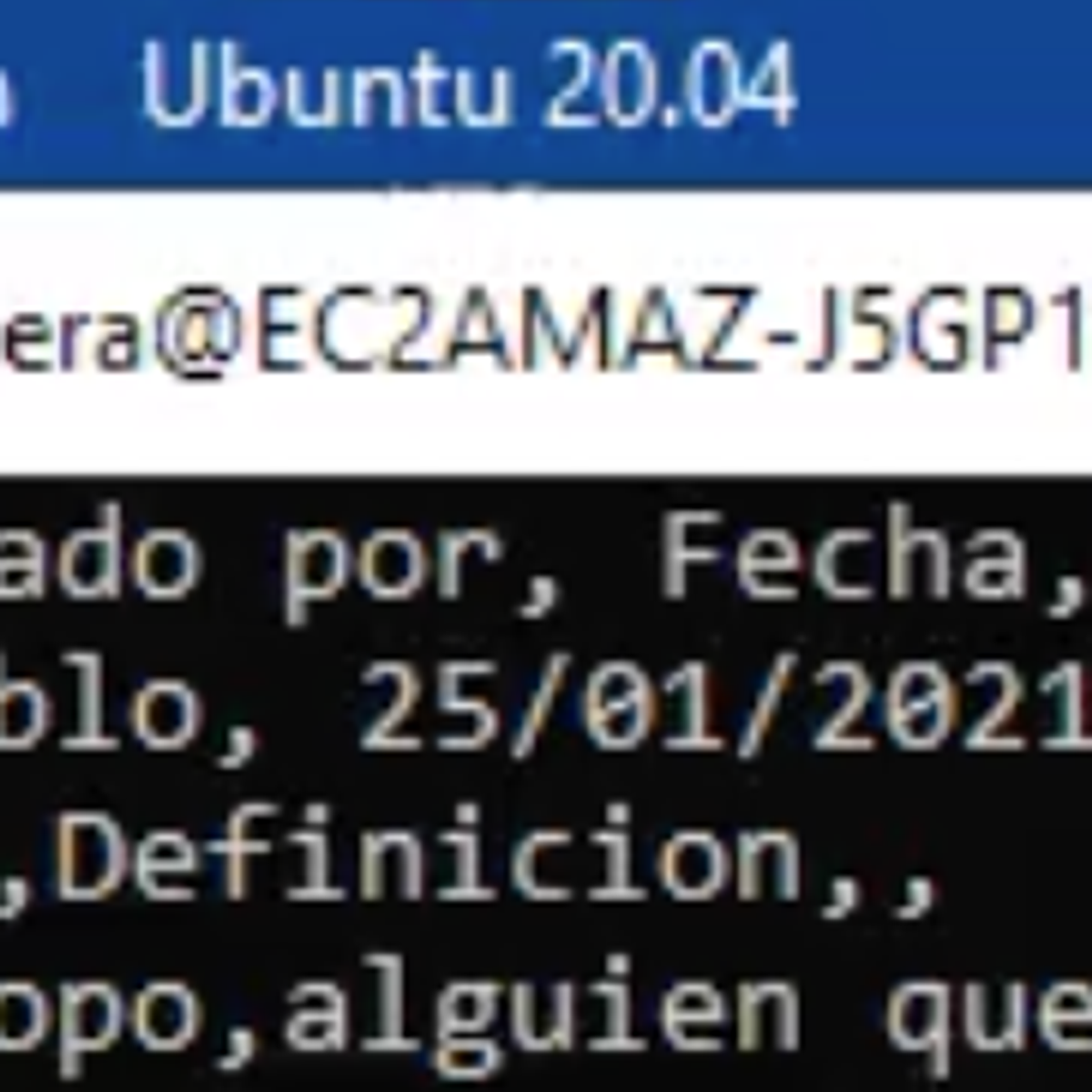

Understanding cloud platforms is increasingly vital. These courses provide foundational knowledge and practical skills for working with major cloud providers like AWS.

Where Do IT Analysts Work? Key Industries

IT Analysts are in demand across virtually every industry, as technology is integral to the operations of most modern organizations. Finance, healthcare, retail, manufacturing, government, education, and technology sectors all rely heavily on IT Analysts.

In finance, analysts might focus on trading systems, risk management platforms, or regulatory compliance software. In healthcare, they could work on electronic health record (EHR) systems, patient portals, or medical imaging software, ensuring compliance with regulations like HIPAA.

Retail analysts might optimize point-of-sale (POS) systems, inventory management software, or e-commerce platforms. Manufacturing analysts could focus on supply chain management systems, enterprise resource planning (ERP) software, or production control systems. The specific focus varies, but the core analytical and problem-solving skills remain constant.

Day-to-Day: Responsibilities of an IT Analyst

Understanding Needs: Systems Analysis and Requirements Gathering

A significant portion of an IT Analyst's time is spent on systems analysis. This involves studying existing IT systems, business processes, and user workflows to understand their strengths, weaknesses, and how they support (or hinder) business objectives. Techniques like observation, interviews, surveys, and document analysis are commonly used.

Based on this analysis, the IT Analyst identifies needs for improvement or entirely new solutions. They then work closely with stakeholders to gather detailed requirements. This process clarifies what the system must do, defining functional requirements (specific features) and non-functional requirements (performance, security, usability).

Effective requirements gathering is crucial for project success. It requires meticulous attention to detail, the ability to ask probing questions, and techniques like use case modeling or user story creation to capture needs accurately. Tools like Jira or specialized requirements management software are often employed.

Making Sense of Data: Interpretation and Workflow Optimization

IT Analysts often analyze data generated by systems to identify trends, patterns, inefficiencies, or potential problems. This could involve analyzing system logs, performance metrics, user activity data, or business transaction data to gain insights that inform system improvements.

A key outcome of analysis is workflow optimization. By mapping out existing business processes (business process modeling), often using notations like BPMN (Business Process Model and Notation), analysts can pinpoint bottlenecks, redundant steps, or areas ripe for automation. They then design improved workflows that leverage technology more effectively.

This requires strong analytical skills and familiarity with process mapping tools. The goal is to make processes faster, more accurate, less costly, and more user-friendly, ultimately improving productivity and efficiency. Tools like Microsoft Visio or dedicated BPM software are frequently used.

These books delve into the specifics of BPMN, a standard notation crucial for process modeling and analysis.

Teamwork Makes the Dream Work: Collaborating with Developers and Stakeholders

Collaboration is central to the IT Analyst role. Daily interactions often involve meetings with software developers to clarify requirements, discuss technical feasibility, and review proposed solutions. They act as the primary point of contact for developers regarding functional questions.

Simultaneously, analysts maintain constant communication with business stakeholders. This includes presenting findings, validating requirements, demonstrating prototypes or system functionalities, managing expectations, and providing updates on project progress. They ensure the solution being built remains aligned with business needs.

Managing these diverse relationships requires adaptability and excellent communication skills. Analysts must be able to mediate disagreements, build consensus, and ensure smooth information flow between all parties involved in a project.

Tools like Microsoft Teams are often central to this collaborative effort.

Documenting Success: Reporting and Post-Implementation Reviews

Thorough documentation is a critical, though sometimes overlooked, aspect of the IT Analyst's job. This includes creating detailed requirements specifications, system design documents, process flow diagrams, use cases, user manuals, and training materials.

Clear documentation serves multiple purposes: it guides the development team, provides a basis for testing, helps users understand the system, and serves as a reference for future maintenance or enhancements. Maintaining accurate and up-to-date documentation throughout the project lifecycle is essential.

After a system is implemented, the IT Analyst often participates in post-implementation reviews. This involves assessing whether the system meets the original objectives and requirements, gathering user feedback, identifying any issues or necessary adjustments, and documenting lessons learned for future projects.

Understanding monitoring tools and techniques helps in evaluating system performance post-implementation.

Building Your Toolkit: Essential Skills for IT Analysts

Technical Foundations: SQL, UML, and System Knowledge

While not always needing deep coding expertise, IT Analysts require a solid technical foundation. Proficiency in SQL (Structured Query Language) is often essential for querying databases to extract and analyze data directly.

Understanding modeling languages like UML (Unified Modeling Language) helps in visually representing system designs, use cases, and data structures, facilitating communication with technical teams. Familiarity with system architecture concepts, networking basics, and database design principles is also crucial.

Knowledge of specific business systems, particularly ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) systems (like SAP or Oracle) or CRM (Customer Relationship Management) systems (like Salesforce), is highly valuable in many roles, as analysts often work on configuring, customizing, or integrating these platforms.

These books offer insights into managing and leveraging IT resources effectively within an organization.

Analytical Acumen: From Gap Analysis to Cost-Benefit Modeling

Strong analytical and problem-solving skills are the bedrock of the IT Analyst profession. This involves the ability to break down complex problems into manageable components, identify root causes, and evaluate potential solutions systematically.

Techniques like gap analysis (comparing current state vs. desired future state), SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats), and root cause analysis are frequently used. Analysts must critically evaluate information from various sources and synthesize it into actionable insights.

Financial acumen is also important, particularly the ability to perform cost-benefit analysis. Analysts often need to justify proposed solutions by demonstrating their potential return on investment (ROI) or contribution to business value, comparing the costs of development and implementation against the expected benefits.

Developing skills in business intelligence tools can enhance analytical capabilities.

These books provide frameworks and tools often used in analysis and consulting contexts.

The Human Element: Communication and Stakeholder Management

Technical and analytical skills are essential, but soft skills truly differentiate effective IT Analysts. Clear communication, both written and verbal, is paramount for conveying complex ideas to diverse audiences, writing documentation, and presenting findings.

Active listening, empathy, and the ability to build rapport are crucial for understanding user needs and managing stakeholder relationships. Facilitation skills are needed for leading meetings and workshops effectively, ensuring all voices are heard and objectives are met.

Negotiation and conflict resolution skills are also valuable, as analysts often need to balance competing priorities, manage scope changes, and mediate disagreements between technical teams and business users. Building trust and maintaining positive working relationships is key to success.

Staying Ahead: Embracing Emerging Skills like AI Literacy

The technology landscape is constantly evolving, and IT Analysts must be lifelong learners. Understanding emerging technologies and their potential business applications is increasingly important. AI literacy, for example, involves understanding the basics of artificial intelligence and machine learning and how they can be applied to automate tasks, improve decision-making, or enhance user experiences.

Familiarity with cloud computing platforms (AWS, Azure, Google Cloud) is now almost a standard requirement, as more organizations migrate their infrastructure and applications to the cloud. Understanding cybersecurity principles is also vital for ensuring systems are designed securely.

Agile methodologies (like Scrum or Kanban) are widely adopted, so familiarity with agile principles and practices, including writing user stories and participating in sprint cycles, is highly beneficial. Continuous learning through online courses, certifications, and industry publications is essential for staying relevant.

These courses explore the practical application of AI tools in business processes and managing solutions involving the Power Platform.

Charting Your Course: Formal Education for IT Analysts

Laying the Groundwork: Relevant Bachelor's Degrees

A bachelor's degree is often the standard entry requirement for IT Analyst positions. Common fields of study include Computer Science (CS), Management Information Systems (MIS), Information Technology (IT), Business Administration (often with an IT concentration), or related engineering fields.

A Computer Science degree provides a strong technical foundation in programming, algorithms, data structures, and systems architecture. An MIS degree typically offers a blend of technical skills and business knowledge, focusing on how technology solves business problems.

Business degrees can also be a pathway, especially if supplemented with relevant IT coursework or minors. The key is acquiring a combination of technical understanding and business process knowledge. Regardless of the major, strong analytical and communication skills developed through coursework are crucial.

Core Curriculum: Essential Coursework

Regardless of the specific degree program, certain types of coursework are particularly beneficial for aspiring IT Analysts. Courses in systems analysis and design are fundamental, teaching methodologies for understanding requirements and designing solutions.

Database design and management courses (including SQL) provide essential skills for working with data, a core component of many IT systems. Courses covering networking concepts, operating systems, and basic programming principles (e.g., in Python or Java) build necessary technical literacy.

Business-oriented courses such as project management, business process management, organizational behavior, and principles of management provide context for how technology fits within the larger organization and how projects are managed.

These courses offer practical introductions to relevant programming languages and tools often encountered by IT Analysts.

Advancing Your Knowledge: Graduate Studies and Specialization

While not always required for entry-level roles, a master's degree can provide deeper specialization and accelerate career advancement. Master's degrees in Information Systems, Business Analytics, Data Science, or an MBA with an IT focus can be particularly valuable.

Graduate programs often allow students to specialize in areas like cybersecurity, data analytics, cloud computing, project management, or enterprise systems. This specialized knowledge can open doors to more senior or specialized analyst roles.

Advanced degrees can also be beneficial for those seeking leadership positions or roles in research or academia. They often involve more in-depth projects and research, further honing analytical and critical thinking skills.

Gaining Experience: The Role of Capstone Projects and Internships

Practical experience is highly valued by employers. Internships undertaken during undergraduate or graduate studies provide invaluable real-world exposure to IT environments, allowing students to apply classroom learning and develop professional skills.

Many degree programs include capstone projects where students work individually or in teams to solve a real-world problem, often for an external client. These projects simulate the work of an IT Analyst, involving analysis, design, implementation (or prototyping), and presentation of a solution.

Building a portfolio of projects, whether through coursework, internships, or personal initiatives, demonstrates practical skills and initiative to potential employers. This hands-on experience is often as important as the degree itself when seeking initial employment.

Beyond the Degree: Alternative Routes to Becoming an IT Analyst

Pivoting Your Career: Transitioning from Related IT Roles

Many successful IT Analysts transition from other roles within the IT field. Individuals working in technical support, help desk, network administration, quality assurance (testing), or even junior development roles often possess valuable technical knowledge and user interaction experience.

These roles provide exposure to business processes, user challenges, and system functionalities. By proactively seeking opportunities to assist with requirements gathering, documentation, or system testing, individuals in these roles can build relevant skills and demonstrate aptitude for an analyst position.

Highlighting transferable skills, such as problem-solving, communication gained from user support, or system knowledge gained from administration, is key when applying for analyst roles. Pursuing relevant certifications or targeted online courses can further strengthen a transition candidate's profile.

These courses cover system administration skills valuable for those transitioning into analyst roles.

Certifications that Count: Boosting Your Credentials

For those without a traditional degree or seeking to formalize their skills, industry certifications can be a powerful alternative or supplement. Certifications demonstrate specific knowledge and competencies valued by employers.

Certifications like the IIBA's Entry Certificate in Business Analysis (ECBA) or Certified Business Analysis Professional (CBAP), or PMI's Professional in Business Analysis (PMI-PBA) are highly respected in the field. CompTIA certifications like A+, Network+, or Security+ can validate foundational IT knowledge.

Vendor-specific certifications related to widely used platforms (e.g., Salesforce Administrator, Microsoft Power Platform Fundamentals, AWS Certified Cloud Practitioner) can also be beneficial, especially if targeting roles involving those technologies. Preparing for and passing these exams requires dedicated study, often aided by online courses and practice tests.

This course specifically prepares learners for the ECBA certification, a great starting point for aspiring analysts.

These courses provide practice for the AWS Cloud Practitioner certification, demonstrating foundational cloud knowledge.

Show, Don't Just Tell: Building a Portfolio with Projects

Regardless of your educational background, a portfolio showcasing practical skills is essential. This is particularly true for career changers or those relying on self-study. A portfolio provides tangible evidence of your abilities.

Projects can range from analyzing a small business's workflow and proposing improvements, designing a database schema for a hypothetical application, creating process maps for a familiar task, or even developing a simple application or website that solves a specific problem.

Include documentation artifacts like requirements documents, use cases, wireframes, or analysis reports in your portfolio. Freelance work, volunteer projects for non-profits, or contributions to open-source projects can also be excellent ways to gain experience and build portfolio pieces.

Online platforms like GitHub can be used to host code or documentation, providing easily shareable proof of your work. Clearly describe the problem, your process, the tools used, and the outcomes for each project.

Even smaller, focused projects using specific tools can demonstrate valuable skills.

Leveraging Your Background: Transferable Skills from Other Fields

Individuals from non-technical backgrounds can successfully transition into IT analysis by leveraging transferable skills. Strong analytical thinking, problem-solving, communication, research, and project management skills developed in fields like law, finance, research, education, or customer service are highly relevant.

The key is to identify how skills from your previous career map onto the requirements of an IT Analyst role. For example, a teacher's ability to explain complex concepts clearly is analogous to an analyst explaining technical solutions to business users. A researcher's analytical rigor is directly applicable to systems analysis.

Making this transition requires dedication. You'll need to supplement your existing skills with foundational IT knowledge, perhaps through targeted online courses, bootcamps, or certifications. Networking with professionals in the field and clearly articulating your transferable skills during interviews is crucial. It's a challenging path, but achievable with persistence and a clear learning plan. OpenCourser offers a vast library of IT & Networking courses to help bridge knowledge gaps.

Climbing the Ladder: Career Progression and Growth Opportunities

Starting Out: Entry-Level Roles

Most IT Analysts begin their careers in entry-level or junior positions. Titles might include Junior IT Analyst, Junior Business Analyst, Systems Support Analyst, or Technical Support Specialist with analytical responsibilities. These roles typically involve supporting senior analysts, focusing on specific tasks like documentation, basic data analysis, requirements elicitation support, or system testing.

Entry-level positions provide essential exposure to the tools, methodologies, and collaborative dynamics of IT projects. It's a crucial period for learning from experienced colleagues, understanding the organization's specific systems and processes, and building foundational skills.

The focus during this stage should be on mastering core competencies, demonstrating reliability and a willingness to learn, and gradually taking on more complex tasks under supervision.

Gaining Expertise: Mid-Career Paths

After gaining a few years of experience, analysts typically progress to mid-level roles like IT Analyst, Systems Analyst, or Business Systems Analyst. At this stage, they take on more responsibility, often leading smaller projects or managing specific modules of larger systems.

Mid-career analysts conduct independent analysis, lead requirements workshops, develop comprehensive solution designs, and work more autonomously with stakeholders and development teams. They possess a deeper understanding of both business domains and technical solutions.

Salaries and responsibilities increase significantly at this level. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median annual wage for computer systems analysts was $103,800 in May 2023. Continued professional development, such as earning advanced certifications or specializing in a particular technology or industry, is common at this stage.

Reaching the Top: Leadership and Management Roles

Experienced IT Analysts with strong leadership potential can advance into senior and management positions. Titles might include Senior IT Analyst, Lead Analyst, IT Project Manager, Solutions Architect, or IT Manager/Director.

Senior analysts often tackle the most complex challenges, mentor junior staff, and play a strategic role in technology decisions. Those moving into project management focus on overseeing project scope, timelines, budgets, and resources. Solutions architects design high-level technical blueprints for major systems.

IT management roles involve overseeing teams of analysts or broader IT functions, setting strategic direction, managing budgets, and liaising with executive leadership. These roles require a blend of deep technical and business understanding, strong leadership skills, and strategic thinking.

These books provide insights relevant to project management and IT leadership.

Finding Your Niche: Specialization Areas

As IT Analysts gain experience, many choose to specialize in specific areas. This allows them to develop deep expertise and become highly sought-after professionals in particular domains.

Common specializations include Cybersecurity Analysis (focusing on security systems and threat analysis), Business Intelligence (BI) Analysis (focusing on data warehousing, reporting, and analytics tools), Cloud Solutions Analysis (specializing in platforms like AWS, Azure, or Google Cloud), ERP/CRM Analysis (deep expertise in specific enterprise systems), or focusing on a particular industry like healthcare or finance.

Specialization often involves targeted training, certifications, and hands-on experience within that niche. It can lead to higher earning potential and more focused career opportunities. Exploring different areas during the early to mid-career stages can help identify interests for potential specialization.

These courses offer deeper dives into cloud platforms and architecture, supporting specialization.

This book provides valuable context on private cloud environments.

Driving Change: The IT Analyst's Role in Modernization

Navigating the Cloud: Involvement in Cloud Migration and Strategy

Cloud computing has fundamentally changed how organizations manage IT infrastructure and applications. IT Analysts play a critical role in planning, executing, and managing cloud migration projects.

This involves assessing existing applications and infrastructure for cloud readiness, identifying suitable cloud services (IaaS, PaaS, SaaS), and developing migration strategies. Analysts help evaluate different cloud providers (like AWS, Azure, Google Cloud) based on cost, performance, security, and business requirements.

Post-migration, analysts may be involved in optimizing cloud resource usage, monitoring performance and costs, and ensuring security configurations are appropriate. Understanding cloud architecture principles and services is essential for analysts involved in these initiatives.

The Expanding Edge: Impact of IoT and Edge Computing

The Internet of Things (IoT) – the network of physical devices embedded with sensors and software – generates vast amounts of data. Edge computing processes this data closer to where it's generated, rather than sending it all back to a central cloud or data center.

IT Analysts may be involved in designing systems that collect, process, and analyze data from IoT devices. This could involve selecting appropriate IoT platforms, defining data flows, and ensuring security for connected devices.

Understanding the implications of edge computing for network bandwidth, data latency, and system architecture is becoming increasingly relevant as these technologies become more prevalent in industries like manufacturing, logistics, and healthcare.

Measuring Success: Quantifying the ROI of Technology Initiatives

A key responsibility for IT Analysts, especially at senior levels, is demonstrating the business value of technology investments. This involves quantifying the potential or actual Return on Investment (ROI) for new systems or improvements.

Analysts build business cases for proposed projects, outlining expected costs (development, implementation, ongoing maintenance) and quantifiable benefits (cost savings, revenue increases, efficiency gains, risk reduction). This often requires working closely with finance departments and business stakeholders.

Post-implementation, analysts may track key performance indicators (KPIs) to measure the actual impact of the solution against the initial projections. Strong analytical skills and an understanding of financial metrics are crucial for effectively quantifying technology's contribution to the bottom line.

Real-World Impact: Case Studies

The impact of IT Analysts is best understood through examples. Consider a company struggling with inefficient manual processes for order fulfillment. An IT Analyst would study the existing workflow, identify bottlenecks, gather requirements from sales and logistics teams, and research potential software solutions (perhaps an ERP module or a dedicated order management system).

The analyst would then design the integration of the chosen system, work with developers on customization, oversee testing, train users, and document the new process. The result could be faster order processing, fewer errors, improved inventory tracking, and better customer satisfaction – tangible benefits driven by the analyst's work.

Similarly, an analyst might lead the overhaul of an outdated CRM system, resulting in improved sales tracking and customer engagement, or implement a new business intelligence platform enabling data-driven decision-making across the organization. These projects highlight the analyst's role in driving significant business improvements.

This book discusses transforming business processes, a core area where IT Analysts contribute.

Navigating the Gray Areas: Ethical Responsibilities

Protecting Information: Data Privacy and Compliance

IT Analysts often work with systems that handle sensitive personal or corporate data. Consequently, understanding and ensuring compliance with data privacy regulations like the EU's GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation) or California's CCPA (California Consumer Privacy Act) is a critical ethical responsibility.

This involves designing systems with privacy considerations in mind ('privacy by design'), ensuring appropriate security measures are in place, documenting data processing activities, and understanding user rights regarding their data.

Analysts must stay informed about relevant regulations in their industry and jurisdiction and ensure the systems they design or recommend adhere to these legal and ethical standards. Failure to do so can result in significant fines and reputational damage for the organization.

This book provides a foundational understanding of information security principles relevant to data protection.

Fairness in Systems: Addressing Algorithmic Bias

As AI and machine learning become more integrated into IT systems (e.g., for decision support, automation, or personalization), the potential for algorithmic bias becomes a significant ethical concern. Biased algorithms can lead to unfair or discriminatory outcomes.

IT Analysts involved in projects utilizing AI/ML need to be aware of this potential. While they may not be building the algorithms themselves, they play a role in defining requirements, selecting vendors, and testing systems.

This includes questioning data sources for potential biases, advocating for transparency in how algorithms work, and ensuring testing procedures check for fairness across different demographic groups. Promoting ethical AI development and deployment is an emerging responsibility for analysts.

Building Sustainably: Environmental Considerations in IT

The environmental impact of technology, particularly data centers and electronic waste, is gaining attention. 'Green IT' focuses on designing, using, and disposing of technology in an environmentally responsible manner.

While not always a primary focus, IT Analysts can contribute to sustainability efforts. This might involve recommending energy-efficient hardware, supporting cloud solutions (which can be more energy-efficient due to economies of scale), designing systems that minimize unnecessary data processing or storage, or considering the lifecycle management of IT assets.

As organizations increasingly focus on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria, analysts may find themselves evaluating the sustainability aspects of technology solutions as part of their analysis.

Speaking Up: Understanding Whistleblowing and Reporting Protocols

IT Analysts may sometimes encounter situations involving unethical practices, security vulnerabilities, or non-compliance within projects or systems. Understanding the organization's protocols for reporting concerns is crucial.

This includes knowing the established channels for raising ethical issues or security concerns, whether it's through management, an internal compliance office, or a dedicated ethics hotline. Understanding whistleblower protections can also be important.

Acting ethically often means having the courage to speak up when something is wrong, even if it's uncomfortable. Professional integrity requires analysts to prioritize ethical conduct and compliance in their work.

The Global Landscape: Opportunities and Considerations

Where the Jobs Are: Regional Demand for IT Analysts

Demand for IT Analysts is generally strong globally, driven by ongoing digital transformation across industries. However, specific demand hotspots can vary based on regional economic factors and the concentration of certain industries.

Major technology hubs (like Silicon Valley, Seattle, Austin in the US; London, Berlin, Dublin in Europe; Bangalore, Singapore in Asia) naturally have high concentrations of IT Analyst roles. However, opportunities exist in most metropolitan areas worldwide as organizations everywhere need to manage and optimize their IT systems.

Researching job market trends in specific regions using resources like LinkedIn, local job boards, or government labor statistics (such as the BLS OOH for Computer Occupations) can provide insights into local demand and salary expectations.

Working Across Borders: Offshore Teams and Collaboration

Globalization has led many organizations to utilize offshore or nearshore teams for IT development and support. IT Analysts often find themselves collaborating with colleagues located in different countries and time zones.

This requires strong cross-cultural communication skills, flexibility in scheduling meetings, and proficiency with collaboration tools that bridge geographical distances. Understanding potential cultural differences in communication styles or work practices can enhance collaboration.

Analysts may also be involved in vendor management when working with outsourced teams, requiring skills in defining clear requirements, managing contracts, and overseeing the quality of deliverables from external partners.

This book explores various aspects of IT outsourcing, relevant when working with global teams.

Understanding Diverse Needs: Cross-Cultural Requirements Gathering

When working on systems intended for a global audience or collaborating with international stakeholders, IT Analysts must be adept at cross-cultural requirements engineering. User needs, expectations, and technological contexts can vary significantly across different cultures and regions.

This requires sensitivity to cultural nuances during interviews and workshops, potentially using visual aids or prototypes to overcome language barriers, and validating requirements with representatives from different target user groups.

Assumptions based on one cultural context may not hold true elsewhere. Analysts need to actively seek out diverse perspectives to ensure the final system is usable and effective for all intended users, regardless of their location or cultural background.

Adapting Solutions: Localization and Internationalization

Related to cross-cultural requirements is the need for localization (adapting a product for a specific locale, including language, date formats, currency, cultural conventions) and internationalization (designing a product so it *can* be easily localized).

IT Analysts are often involved in specifying requirements for internationalization during the initial design phase. This might include ensuring the system supports multiple languages (e.g., using Unicode), designing user interfaces that can accommodate text expansion in different languages, and avoiding hard-coded text or culturally specific icons.

They may also oversee the localization process itself, working with translators and regional experts to ensure the adapted version is accurate and culturally appropriate. This requires attention to detail and coordination across multiple teams.

Your Questions Answered: FAQs about the IT Analyst Career

IT Analyst vs. Data Scientist/Business Analyst: What's the Difference?

While there's overlap, these roles have distinct focuses. An IT Analyst primarily focuses on *IT systems* – how they function, how they can be improved, and how they meet business needs. They bridge IT and business processes.

A Business Analyst (BA) focuses more broadly on *business problems and opportunities*, which may or may not involve an IT solution. They analyze business processes, identify needs, and define requirements, but the solution might be process changes, policy updates, or organizational restructuring, not just technology. The Business category on OpenCourser offers relevant courses.

A Data Scientist focuses specifically on extracting insights from *data*, often using complex statistical modeling, machine learning, and programming skills (like Python or R). Their goal is typically prediction, pattern discovery, or data-driven decision support, requiring deeper mathematical and statistical expertise than usually expected of an IT Analyst. Explore Data Science courses for comparison.

Can I Become an IT Analyst with a Non-Technical Degree?

Yes, absolutely. While degrees in CS, MIS, or IT are common, many successful IT Analysts come from diverse academic backgrounds, including business, humanities, social sciences, or liberal arts. The key is demonstrating the required analytical, problem-solving, and communication skills.

If you have a non-technical degree, you'll likely need to supplement it with targeted learning in foundational IT concepts, systems analysis methodologies, database basics (SQL), and possibly specific tools or platforms relevant to the jobs you're targeting. Online courses, certifications (like ECBA), and building a project portfolio are crucial steps.

Highlight your transferable skills – critical thinking, research abilities, writing proficiency, presentation skills – and clearly articulate your passion for technology and your commitment to learning the necessary technical skills. Networking and informational interviews can also be very helpful.

How is AI Changing the IT Analyst Role?

AI is augmenting, not replacing, the IT Analyst role. AI tools can automate certain tasks like analyzing system logs, identifying patterns in requirements, or even generating basic code or documentation. This frees up analysts to focus on more complex, strategic, and human-centric aspects of the role.

Analysts need to become proficient in leveraging AI tools to enhance their productivity and analysis capabilities (AI literacy). They will also be increasingly involved in projects implementing AI solutions, requiring them to understand AI concepts, evaluate AI vendors, define requirements for AI systems, and consider the ethical implications (like bias).

The core skills of critical thinking, problem-solving, stakeholder communication, and understanding business context remain essential and are areas where human analysts provide unique value that AI currently cannot replicate.

What's a Realistic Timeline for a Career Change?

The timeline for transitioning into an IT Analyst role varies greatly depending on your starting point (existing skills, background) and the intensity of your efforts. For someone with a related background (e.g., tech support) proactively learning and seeking opportunities, it might take 6-18 months to land a junior analyst role.

For someone from a completely unrelated field, it might take 1-3 years. This typically involves dedicated self-study (online courses, books), potentially a formal bootcamp or certification program, building a portfolio through personal or freelance projects, networking, and applying for entry-level positions.

It's important to set realistic expectations. It requires sustained effort to acquire the necessary knowledge and skills. Start by focusing on foundational concepts and gradually build expertise and practical experience. Utilize resources like the OpenCourser Learner's Guide for tips on effective self-study.

Freelance vs. Full-Time: Which Path is Right?

Both freelance (contracting) and full-time employment are viable options for IT Analysts. Full-time roles typically offer more stability, benefits (health insurance, retirement plans), structured career progression within a single organization, and potentially deeper immersion in a specific industry or system.

Freelancing offers greater flexibility, variety in projects and clients, potentially higher hourly rates (though income can be less predictable), and the autonomy of being your own boss. However, freelancers are responsible for finding their own work, managing finances (including taxes and insurance), and may lack the consistent team environment of a full-time role.

The choice depends on individual priorities regarding stability, autonomy, benefits, and work-life balance. Some analysts transition to freelancing after gaining significant experience in full-time roles, leveraging their expertise and network.

Setting Up for Success: Essential Tools for a Home Lab?

While not strictly mandatory, setting up a simple home lab can be beneficial for learning and experimenting, especially for those new to IT. You don't need expensive hardware initially.

Start with virtualization software like VirtualBox (free) or VMware Workstation Player (free for non-commercial use) on your existing computer. This allows you to install and run different operating systems (like Linux distributions or Windows Server evaluation editions) in virtual machines (VMs) without affecting your main system.

Within these VMs, you can practice installing software, configuring networks (virtual networking), setting up basic databases (like MySQL or PostgreSQL), experimenting with scripting (Bash, Python, PowerShell), or even exploring web server software (like Apache or Nginx). Access to cloud platforms (AWS Free Tier, Azure Free Account, Google Cloud Free Tier) also provides excellent opportunities to experiment with cloud services at little to no cost.

The journey to becoming an IT Analyst is one of continuous learning and adaptation, blending technical understanding with sharp business insight. It's a challenging but rewarding career path that places you at the intersection of technology and organizational strategy, offering numerous opportunities to solve complex problems and drive meaningful change. Whether you're starting with a formal degree, pivoting from another field, or building skills through online learning, the key lies in cultivating analytical rigor, mastering communication, and embracing the ever-evolving world of technology. Resources like OpenCourser provide access to thousands of courses to support your learning journey every step of the way.