Water Resources Manager

Water Resources Manager: A Comprehensive Career Guide

Water Resources Management is a critical field focused on the planning, developing, distributing, and managing the optimal use of water resources. Professionals in this area tackle complex challenges related to water availability, quality, and accessibility. They work at the intersection of environmental science, engineering, policy, and economics to ensure water resources are used sustainably and equitably for current and future generations.

Working as a Water Resources Manager often involves engaging with diverse stakeholders, from government agencies and private companies to local communities and environmental groups. The role demands a blend of technical expertise, strategic thinking, and strong communication skills. It's a career path that offers the chance to make a tangible impact on environmental health and community well-being, addressing some of the most pressing global issues like water scarcity and climate change adaptation.

Understanding the Role

Definition and Scope of Water Resources Management

Water Resources Management encompasses the multifaceted task of overseeing the entire lifecycle of water – from its source to its use and return to the environment. This includes managing surface water like rivers and lakes, groundwater aquifers, and even atmospheric water in some contexts. The scope involves not just the quantity of water but also its quality, ensuring it's fit for various purposes, including drinking, agriculture, industry, and maintaining healthy ecosystems.

The field integrates principles from hydrology, environmental science, engineering, economics, law, and social sciences. Managers must understand complex water systems, predict future demands and supplies under various scenarios (like population growth or climate change), and develop strategies that balance competing needs. This often requires navigating intricate legal frameworks and policy landscapes governing water rights and usage.

Ultimately, the goal is to achieve sustainable water use, which means meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own water needs. This involves protecting water sources from pollution, promoting water conservation, and ensuring fair access for all users.

Key Responsibilities of a Water Resources Manager

A Water Resources Manager wears many hats. Core responsibilities often include developing long-term water management plans for a region, watershed, or organization. This involves analyzing water availability, projecting future needs, and identifying potential challenges like drought or declining water quality. They evaluate various management options, considering their technical feasibility, economic cost, environmental impact, and social acceptability.

Implementing these plans is another key function. This might involve overseeing the construction or maintenance of water infrastructure (like dams, reservoirs, or treatment plants), coordinating water allocation among different users, or implementing water conservation programs. They monitor water systems, collect and analyze data on water levels, flow rates, and quality parameters to ensure plans are effective and regulations are met.

Communication and stakeholder engagement are crucial. Managers must liaise with government agencies, elected officials, industry representatives, agricultural users, environmental organizations, and the public. They present findings, advocate for specific policies or projects, mediate conflicts over water use, and educate stakeholders about water issues and conservation practices.

These books provide a solid overview of the principles and practices involved in managing water resources effectively.

Importance in Addressing Global Water Challenges

Water is fundamental to life, economic development, and environmental health, yet it faces unprecedented pressures globally. Population growth, urbanization, industrialization, and changing consumption patterns are increasing demand. Simultaneously, climate change is altering precipitation patterns, intensifying droughts and floods, and impacting water quality, making effective management more critical than ever.

Water Resources Managers are at the forefront of addressing these challenges. They develop strategies for adapting to climate change, such as building more resilient infrastructure or promoting water-saving technologies in agriculture. They work to combat water scarcity by exploring alternative water sources like desalination or reclaimed wastewater and implementing demand management measures.

Furthermore, ensuring equitable access to clean water and sanitation is a key aspect of the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 6). Water Resources Managers play a vital role in achieving this goal by designing and implementing policies and projects that prioritize vulnerable populations and promote fair allocation of water resources. Their work directly contributes to public health, poverty reduction, and environmental sustainability.

Understanding the global context of water challenges is essential. These courses offer insights into the complexities of global water issues and sustainable development goals.

Historical Evolution of the Role

Water management is not a new concept; civilizations have managed water resources for millennia, building canals for irrigation, aqueducts for supply, and levees for flood control. However, the focus and complexity have evolved significantly. Early efforts often centered purely on harnessing water for specific purposes, primarily agriculture and domestic supply, often with limited consideration for environmental impacts or long-term sustainability.

The 20th century saw large-scale infrastructure development, with the construction of major dams, reservoirs, and distribution networks driven by engineering capabilities and growing demands. Management was often fragmented, with different agencies handling different aspects like water supply, flood control, or hydropower, sometimes leading to conflicting objectives and unintended consequences.

More recently, there has been a paradigm shift towards Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM). This approach recognizes the interconnectedness of water systems and promotes coordinated development and management of water, land, and related resources. It emphasizes stakeholder participation, environmental sustainability, and the consideration of water's economic value, moving beyond purely technical solutions to incorporate social, economic, and ecological dimensions. The role of the Water Resources Manager has thus become more holistic, requiring a broader skillset and a collaborative approach.

Core Responsibilities of a Water Resources Manager

Planning and Implementing Water Conservation Strategies

A key function of a Water Resources Manager is developing and executing strategies to promote efficient water use. This involves analyzing current water consumption patterns across different sectors – residential, agricultural, industrial – and identifying opportunities for reduction. Managers might design public awareness campaigns, advocate for water-wise landscaping ordinances, or work with industries to adopt water-saving technologies.

Implementation often requires collaboration. For instance, promoting efficient irrigation techniques in agriculture might involve working with farmers, extension services, and technology providers. In urban areas, managers might oversee programs offering rebates for water-efficient appliances or conduct water audits for large consumers. Monitoring the effectiveness of these programs through data collection and analysis is crucial for adaptive management.

Developing robust water conservation plans helps communities and ecosystems become more resilient, especially in the face of drought and growing demand. It's a proactive approach that reduces the need for costly new water supply infrastructure and minimizes environmental strain.

Regulatory Compliance and Policy Advocacy

Water management operates within a complex web of local, state, federal, and sometimes international laws and regulations. Water Resources Managers must ensure their organization's or jurisdiction's activities comply with standards related to water quality (like the Clean Water Act in the US), water rights allocation, environmental protection (e.g., endangered species), and infrastructure safety.

This involves staying abreast of evolving regulations, obtaining necessary permits, conducting required monitoring and reporting, and implementing measures to meet compliance standards. Managers often work closely with legal counsel and regulatory agencies. Non-compliance can result in significant fines, legal action, and damage to public trust.

Beyond compliance, managers often engage in policy advocacy. They may provide technical expertise to policymakers developing new water laws or regulations, advocate for funding for water projects, or participate in stakeholder forums to shape water policy decisions. Their understanding of both the technical and practical aspects of water management is invaluable in crafting effective and equitable water policies.

These courses and books provide insights into the legal and policy frameworks governing water resources.

Crisis Management (Droughts, Floods, Contamination)

Water-related crises, such as severe droughts, major floods, or contamination events, demand swift and effective responses. Water Resources Managers play a critical role in preparing for and managing these situations. This includes developing emergency response plans, establishing communication protocols, and coordinating actions with emergency services, public health officials, and other agencies.

During a drought, managers might implement mandatory water restrictions, secure emergency water supplies, and communicate conservation messages to the public. In flood situations, they might be involved in operating flood control structures, issuing warnings, and assessing damage to water infrastructure post-event. If water contamination occurs, they coordinate testing, identify the source, implement treatment solutions, issue public health advisories, and oversee remediation efforts.

Effective crisis management requires foresight, clear decision-making under pressure, and excellent communication skills. Lessons learned from past events are often incorporated into future planning to improve resilience and response capabilities.

Collaboration with Environmental Scientists and Engineers

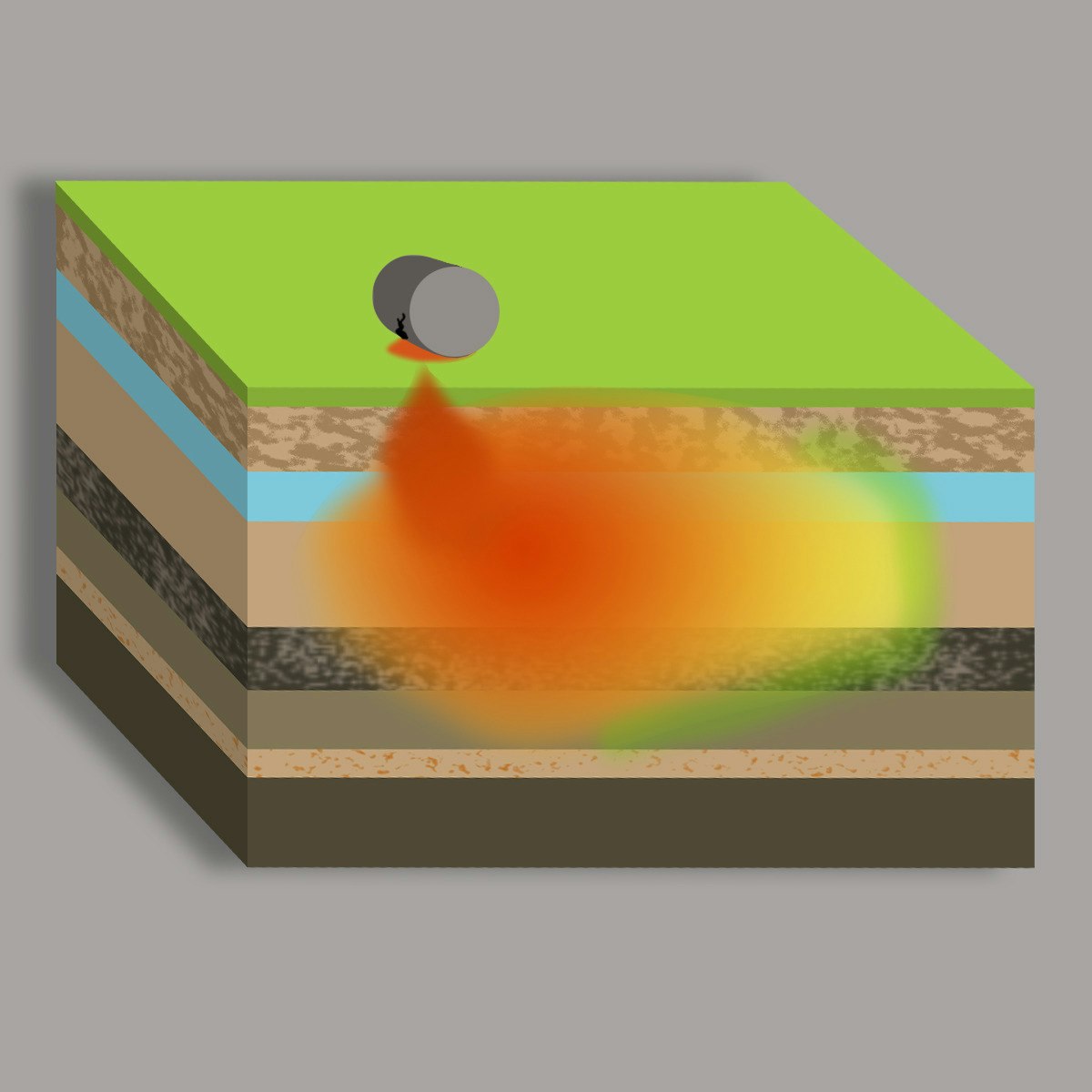

Water Resources Management is inherently interdisciplinary. Managers work closely with a range of specialists, particularly environmental scientists and engineers. Environmental scientists provide expertise on ecosystem health, water quality monitoring, contaminant fate and transport, and the ecological impacts of water projects.

Environmental scientists contribute vital data and analysis for planning and decision-making. They might conduct environmental impact assessments, monitor wetland health, or study the effects of pollution on aquatic life. Their insights help ensure that management strategies protect and restore natural systems.

Civil engineers, particularly those specializing in water resources or environmental engineering, design and oversee the construction of water infrastructure. This includes dams, pipelines, treatment plants, levees, and stormwater management systems. Managers collaborate with engineers on project planning, design review, operational strategies, and infrastructure maintenance, ensuring projects are technically sound, cost-effective, and meet management objectives.

This close collaboration ensures that management decisions are grounded in sound science and engineering principles, leading to more effective and sustainable outcomes.

Formal Education Pathways

Undergraduate Degrees

A bachelor's degree is typically the minimum educational requirement for entry-level positions in water resources. Relevant fields include Environmental Science, Civil Engineering (with a water resources or environmental focus), Hydrology, Geology, Environmental Studies, or Agricultural Engineering. These programs provide foundational knowledge in physical sciences, mathematics, and core principles related to water.

Coursework often covers topics like fluid mechanics, hydrology, water chemistry, ecology, environmental policy, statistics, and geographic information systems (GIS). Engineering programs emphasize design and analysis of water systems, while science programs focus more on environmental processes and assessment. Strong analytical and problem-solving skills are developed through coursework and lab exercises.

Choosing a program with a specific water resources track or concentration can be advantageous. Look for universities with strong programs in environmental science or civil/environmental engineering, often listed under Engineering or Environmental Sciences categories.

Graduate Programs and Research Opportunities

For many specialized roles, particularly in research, policy analysis, or management positions requiring advanced technical expertise, a graduate degree (Master's or Ph.D.) is often preferred or required. Master's programs offer deeper specialization in areas like hydrogeology, water quality modeling, water policy and economics, or environmental engineering.

Ph.D. programs are research-intensive and prepare individuals for academic careers or high-level research positions in government agencies or consulting firms. Graduate studies typically involve advanced coursework, independent research culminating in a thesis or dissertation, and opportunities to publish findings and present at conferences. This advanced training develops critical thinking, sophisticated analytical skills, and expertise in a specific niche within water resources.

Pursuing graduate studies allows for in-depth exploration of complex water issues and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in the field. Many universities offer specialized graduate programs in water resources management or related disciplines.

Certifications and Licensure

While not always mandatory for all roles, professional certifications and licenses can significantly enhance career prospects and credibility. For those with engineering backgrounds, obtaining a Professional Engineer (PE) license is highly valuable, particularly for roles involving the design and oversight of public infrastructure projects. Requirements vary by state but typically involve education, experience, and passing exams.

Other relevant certifications exist for specific areas. For example, professionals involved in project management might pursue the Project Management Professional (PMP) certification. There are also specialized certifications related to water treatment plant operation, stormwater management, erosion control, or floodplain management offered by various professional organizations.

These credentials demonstrate a commitment to the profession and a verified level of expertise. Employers often view certifications favorably as they indicate a high standard of competence and adherence to ethical practices.

Internships and Co-op Programs

Practical experience is invaluable in the water resources field. Internships and cooperative education (co-op) programs provide students with hands-on experience, allowing them to apply classroom knowledge in real-world settings. These opportunities expose students to the day-to-day tasks of water professionals, whether in government agencies, consulting firms, non-profits, or utilities.

Internships help build technical skills, develop professional networks, and gain insights into different career paths within the field. Experiences might involve fieldwork (water sampling, site assessments), data analysis, assisting with report writing, using modeling software, or attending stakeholder meetings. Many employers prefer candidates with internship or co-op experience, as it demonstrates initiative and practical understanding.

Students should actively seek out these opportunities through university career services, professional organizations, and direct outreach to potential employers. Starting early and gaining diverse experiences can provide a significant advantage when entering the job market.

Online and Self-Directed Learning

Key Skills Taught by Online Courses

The digital age offers unprecedented access to learning resources, making online courses an excellent way to acquire or enhance skills crucial for water resources management. Key technical skills often targeted include Geographic Information Systems (GIS) for spatial analysis and mapping, hydrological modeling software (like HEC-RAS, SWAT, or MODFLOW) for simulating water systems, and data analysis techniques for interpreting monitoring data and forecasting trends.

Online platforms also offer courses in relevant theoretical areas like environmental policy, water law, climate science, sustainability principles, and project management. Soft skills, such as communication, negotiation, and stakeholder engagement, are also increasingly covered in online formats. These platforms allow learners to study at their own pace and often focus on practical application.

OpenCourser provides a vast catalog where you can search for courses covering these essential skills from various providers. Features like summarized reviews and syllabi help learners choose the best fit for their needs.

These online courses cover foundational skills like GIS and remote sensing, often crucial for water resource analysis.

Portfolio-Building Through Personal Projects

Supplementing formal or online learning with personal projects is an excellent way to solidify skills and demonstrate capabilities to potential employers. Aspiring Water Resources Managers can undertake projects like analyzing local water quality data, modeling a small watershed's hydrology using publicly available data and software, or developing a hypothetical water conservation plan for their community.

These projects allow learners to apply theoretical knowledge, troubleshoot problems, and produce tangible outputs (maps, reports, models). Documenting these projects, perhaps on a personal website or platform like GitHub, creates a portfolio that showcases practical skills and initiative beyond coursework or certifications.

Presenting a well-documented project during interviews can be highly effective. It provides concrete evidence of technical proficiency, problem-solving ability, and passion for the field, setting candidates apart.

Balancing Online Learning with Formal Education

Online courses can effectively supplement traditional degree programs or serve as a pathway for career pivoters. University students can use online resources to deepen their understanding of specific topics not covered extensively in their curriculum or to gain proficiency in software tools before entering the job market. Professionals can use them for continuing education, skill updates, or exploring new specializations within water resources.

For those transitioning into the field without a directly relevant degree, online courses and certificate programs can provide essential foundational knowledge and technical skills. However, it's important to be realistic; while online learning is powerful, it may not fully substitute for the comprehensive education and networking opportunities of a formal degree program, especially for roles requiring licensure like a PE.

A balanced approach often works best, combining the structured learning of formal education (if pursued) with the flexibility and targeted skill development offered by online platforms. OpenCourser's Learner's Guide offers tips on creating self-structured curricula and maximizing the value of online learning.

Recognized Platforms for Skill Validation

While acquiring skills is paramount, demonstrating that knowledge to employers is equally important. Many online course platforms offer certificates upon completion, which can be added to resumes or LinkedIn profiles. Some platforms partner with universities or industry bodies, adding weight to their credentials.

Beyond course completion certificates, look for platforms offering assessments or projects that are graded or reviewed, providing more robust validation. Industry-recognized certifications (like GISP for GIS professionals or specialized water treatment operator licenses) obtained through dedicated programs often carry more weight than general course certificates.

When choosing online learning options, consider the reputation of the provider and the potential for skill validation. Focus on building a portfolio of projects alongside certifications to provide concrete proof of your abilities.

Career Progression and Opportunities

Entry-Level Roles

Graduates typically start in entry-level positions that provide foundational experience. Titles might include Water Quality Analyst, Hydrologic Technician, Environmental Scientist (entry-level), Junior Engineer, or GIS Technician. These roles often involve fieldwork (sampling, monitoring), data collection and management, basic analysis, report preparation, and supporting senior staff.

These positions offer opportunities to learn practical skills, understand regulatory processes, and become familiar with specific water systems or challenges. Working under the guidance of experienced professionals helps build technical competence and professional judgment. This phase is crucial for developing a strong base for future advancement.

Mid-Career Advancement

With several years of experience and demonstrated competence, professionals can advance to mid-career roles. These might include Water Resources Planner, Project Manager, Senior Environmental Scientist, or Water Resources Engineer. Responsibilities typically expand to include leading smaller projects, managing budgets and schedules, supervising junior staff, conducting more complex analyses, and interacting more directly with clients or stakeholders.

At this stage, specialization often deepens. Individuals might focus on areas like groundwater modeling, watershed management, water rights, or specific types of infrastructure projects. Obtaining professional licensure (like the PE) or relevant certifications often facilitates advancement to these levels. Strong technical skills combined with effective communication and project management abilities are key.

Leadership Positions

Seasoned professionals with extensive experience, proven leadership capabilities, and often advanced degrees or certifications can progress to senior leadership roles. Titles could include Director of Water Resources, Chief Hydrologist, Principal Engineer/Scientist, Sustainability Manager, or Water Utility Director. These positions involve significant strategic planning, policy development, large-scale program management, budget oversight, and representing the organization externally.

Leadership roles require a broad understanding of technical, financial, political, and social aspects of water management. Strong leadership, strategic vision, negotiation skills, and the ability to manage complex teams and initiatives are essential. These individuals often play a key role in shaping the future direction of water management within their organization or region.

Sector-Specific Opportunities

Water Resources Managers work across various sectors, each offering distinct opportunities and work environments. Public sector roles are found in federal agencies (e.g., EPA, USGS, Army Corps of Engineers), state water resource departments, regional water authorities, and municipal water utilities. These roles often focus on regulation, long-term planning, public infrastructure, and resource protection.

The private sector employs managers in environmental consulting firms, engineering companies, and industries with significant water footprints (e.g., agriculture, energy, manufacturing). Consultants advise clients on compliance, project design, and management strategies. Industry roles focus on optimizing water use, managing wastewater, and ensuring environmental stewardship.

Non-profit organizations and academic institutions also employ water resources professionals. Non-profits often focus on advocacy, conservation projects, and community-based initiatives. Academia involves research, teaching, and training the next generation of water professionals. Each sector provides unique pathways and contributions to the field.

Industry Trends and Challenges

Climate Change Adaptation Strategies

Climate change poses significant challenges to water resources management globally. Changing precipitation patterns, rising temperatures, increased frequency of extreme weather events (droughts and floods), and sea-level rise directly impact water availability, quality, and demand. Water Resources Managers are increasingly focused on developing and implementing adaptation strategies to build resilience.

These strategies include diversifying water supply sources (e.g., water reuse, desalination), updating infrastructure design standards to withstand extreme events, implementing advanced water conservation measures, restoring natural infrastructure like wetlands and floodplains, and developing flexible water allocation systems. Scenario planning using climate model projections is becoming standard practice to inform long-term investments.

Integrating climate change considerations into all aspects of water planning and management is crucial for ensuring sustainable water futures. According to the World Bank, water is the primary medium through which climate change impacts will be felt by people, ecosystems, and economies.

These courses delve into the intersection of climate change, adaptation, and water resources.

Technological Innovations

Technology is rapidly transforming water resources management. Innovations like remote sensing (satellites, drones) provide enhanced data for monitoring large areas. Advanced sensor networks enable real-time monitoring of water quality and quantity in distribution systems ("smart water grids"). Sophisticated modeling software allows for more accurate simulation and prediction of water system behavior.

Data analytics and machine learning are being used for improved demand forecasting, leak detection, and optimizing treatment processes. Advances in water treatment technologies, such as membrane filtration and advanced oxidation processes, allow for the treatment of more challenging water sources and enhance water reuse possibilities. These technological advancements improve efficiency, reduce costs, and enhance decision-making capabilities.

Staying abreast of relevant technological developments is important for professionals in the field. Continued learning, often facilitated by online courses or professional workshops, is necessary to leverage these new tools effectively.

Funding and Political Barriers

Despite the critical importance of water resources, securing adequate funding for infrastructure maintenance, upgrades, and new projects remains a significant challenge. Many water systems face aging infrastructure and deferred maintenance backlogs. Political cycles and competing budget priorities can make long-term investment difficult to secure.

Water pricing that reflects the true cost of service and resource scarcity can be politically sensitive but is often necessary for financial sustainability. Navigating political landscapes, building consensus among diverse stakeholders with competing interests, and effectively communicating the value of water investments are crucial skills for managers. Overcoming these financial and political hurdles is essential for implementing needed management strategies.

Understanding the economics and financing mechanisms related to water is becoming increasingly important for managers.

Public-Private Partnership Models

Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) are increasingly explored as a mechanism to finance, design, build, and operate water infrastructure and services. In a PPP arrangement, public sector entities collaborate with private companies, leveraging private sector capital, expertise, and efficiency while retaining public oversight and ensuring public interest goals are met.

PPPs can take various forms, from simple service contracts to long-term concessions. They can potentially accelerate project delivery and introduce innovation. However, they also require careful structuring, robust contracts, and strong regulatory oversight to ensure accountability, affordability, and equitable service delivery.

Water Resources Managers may be involved in evaluating the feasibility of PPPs, negotiating contracts, and overseeing partnership performance. Understanding the potential benefits and risks associated with different PPP models is becoming an important aspect of modern water management.

Ethical and Sustainability Considerations

Equitable Water Distribution

Ensuring fair and equitable access to water resources is a fundamental ethical challenge in water management. Historically and currently, disparities exist in access to safe drinking water and sanitation, often disproportionately affecting low-income communities, marginalized groups, and rural populations. Management decisions regarding water allocation, infrastructure investment, and pricing policies can either exacerbate or alleviate these inequities.

Water Resources Managers have an ethical responsibility to promote fairness. This involves considering the needs of all users, ensuring transparent and participatory decision-making processes, and designing policies that protect vulnerable populations. Addressing historical injustices and ensuring affordability are key components of equitable water distribution.

The concept of water as a human right underscores the importance of prioritizing access for basic needs. Managers must navigate complex trade-offs between competing demands while upholding principles of fairness and justice.

Environmental Justice Implications

Water management decisions can have significant environmental justice implications. Environmental justice refers to the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies. Historically, polluting facilities and environmental hazards have often been sited disproportionately in or near low-income communities and communities of color.

In the water context, this can manifest as unequal exposure to water pollution, inadequate flood protection, or lack of investment in water infrastructure in disadvantaged areas. Water Resources Managers must actively consider the potential environmental justice impacts of their decisions, engage with affected communities, and strive for outcomes that distribute environmental benefits and burdens fairly.

This requires incorporating social equity considerations into environmental assessments and planning processes, ensuring that the voices of vulnerable communities are heard and their concerns addressed.

Conflict Resolution in Transboundary Water Management

Many rivers, lakes, and aquifers cross political boundaries, creating shared water resources known as transboundary waters. Managing these resources requires cooperation between different jurisdictions (states or countries) and can be a source of tension or conflict, especially in water-scarce regions. Different users may have conflicting needs and priorities regarding water quantity, quality, and infrastructure development.

Water Resources Managers involved in transboundary issues often engage in water diplomacy, facilitating dialogue, negotiation, and the development of cooperative agreements or treaties. This requires strong negotiation skills, cultural sensitivity, and an understanding of international water law and institutional frameworks. The goal is to find mutually beneficial solutions that promote peaceful cooperation and sustainable management of shared resources.

These courses and topics explore the complexities of governing shared water resources.

Balancing Economic and Ecological Priorities

A central challenge in water resources management is balancing the economic demands for water (for agriculture, industry, energy, urban supply) with the ecological needs of aquatic ecosystems. Over-abstraction or pollution can severely damage rivers, wetlands, and groundwater-dependent ecosystems, leading to biodiversity loss and impairing essential ecosystem services.

Managers must often make difficult trade-offs. This involves assessing the economic benefits of water use against the environmental costs of degradation. Tools like environmental flow assessments help determine the quantity, timing, and quality of water flows required to sustain freshwater ecosystems. Implementing policies that incentivize water conservation, protect critical habitats, and manage pollution sources are key strategies.

Achieving sustainability requires integrating economic development goals with environmental protection, recognizing that healthy ecosystems underpin long-term water security and human well-being. This often involves innovative approaches that seek synergies, such as nature-based solutions for flood management or water treatment.

Water Resources Management in a Changing Climate

Role in Mitigating Flood and Drought Risks

Climate change is intensifying the water cycle, leading to more frequent and severe floods and droughts in many regions. Water Resources Managers are crucial in developing strategies to mitigate these risks. For flood risk reduction, this involves a combination of structural measures (levees, dams, floodwalls) and non-structural approaches (land-use planning, early warning systems, floodplain restoration).

Drought risk management involves improving water storage (surface and groundwater), promoting water conservation and efficiency across all sectors, developing drought contingency plans, and exploring alternative water supplies like reuse or desalination. Managers analyze climate projections to understand future risks and design adaptive strategies that can function under a range of potential climate scenarios.

Effective risk mitigation requires integrated planning that considers the entire watershed and involves collaboration across multiple agencies and stakeholder groups. It's about building resilience in both physical infrastructure and management systems.

Integration with Renewable Energy Systems

The water and energy sectors are deeply interconnected (the "water-energy nexus"). Traditional energy production often requires significant amounts of water for cooling or extraction, while water treatment and distribution consume substantial energy. Climate change mitigation efforts, particularly the shift towards renewable energy, present both challenges and opportunities for water management.

Hydropower remains a major renewable energy source, requiring careful management to balance energy production with environmental flows and other water uses. Other renewables like solar and wind generally have lower water footprints than thermal power plants, but their deployment might still interact with land and water resources. Managers may be involved in assessing the water implications of energy projects or exploring opportunities for co-locating renewable energy installations (e.g., floating solar panels on reservoirs) with water infrastructure.

Understanding these interdependencies is crucial for integrated planning that optimizes both water and energy sustainability in a changing climate.

Case Studies of Climate-Resilient Projects

Examining real-world examples provides valuable insights into effective climate adaptation in water management. Case studies might showcase projects like Singapore's "Four National Taps" strategy (local catchment, imported water, NEWater reuse, desalination) for water security, the Netherlands' "Room for the River" program creating space for floodwaters, or California's efforts in groundwater recharge and demand management during prolonged droughts.

Other examples could include community-based rainwater harvesting initiatives in India, the use of nature-based solutions like mangrove restoration for coastal flood protection in Vietnam, or advanced water recycling projects in arid regions like Israel or Namibia. Analyzing these cases helps identify successful approaches, challenges encountered, and lessons learned that can inform future projects.

Learning from these diverse experiences fosters innovation and helps managers adapt strategies to their specific local contexts.

Funding Mechanisms for Adaptation Initiatives

Implementing climate adaptation projects requires significant investment. Traditional funding sources like government budgets and user fees may not be sufficient. Water Resources Managers often need to explore and secure funding from diverse sources, including international climate funds (e.g., Green Climate Fund), development banks, national adaptation funds, private sector investment, and innovative financing mechanisms.

Developing compelling business cases that demonstrate the long-term economic benefits of adaptation (e.g., avoided damages from floods or droughts) is crucial for attracting investment. Blended finance models, combining public and private capital, are also gaining traction. Managers need skills in financial planning, grant writing, and navigating complex funding application processes to secure the resources needed for climate resilience.

Understanding landscape finance and investment strategies can be beneficial.

Tools and Technologies

Hydrological Modeling Software

Hydrological models are essential tools for understanding and predicting the behavior of water systems. Software packages like HEC-HMS and HEC-RAS (developed by the US Army Corps of Engineers), SWAT (Soil and Water Assessment Tool), or MODFLOW (for groundwater) allow managers to simulate rainfall-runoff processes, river hydraulics, water quality transport, and groundwater flow.

These models are used for various applications, including flood forecasting, water supply planning, assessing the impacts of land-use change or climate change, designing hydraulic structures, and evaluating different management scenarios. Proficiency in selecting, calibrating, and interpreting the results of these models is a valuable skill for Water Resources Managers and Analysts.

Online courses and workshops are widely available to learn these specific software tools.

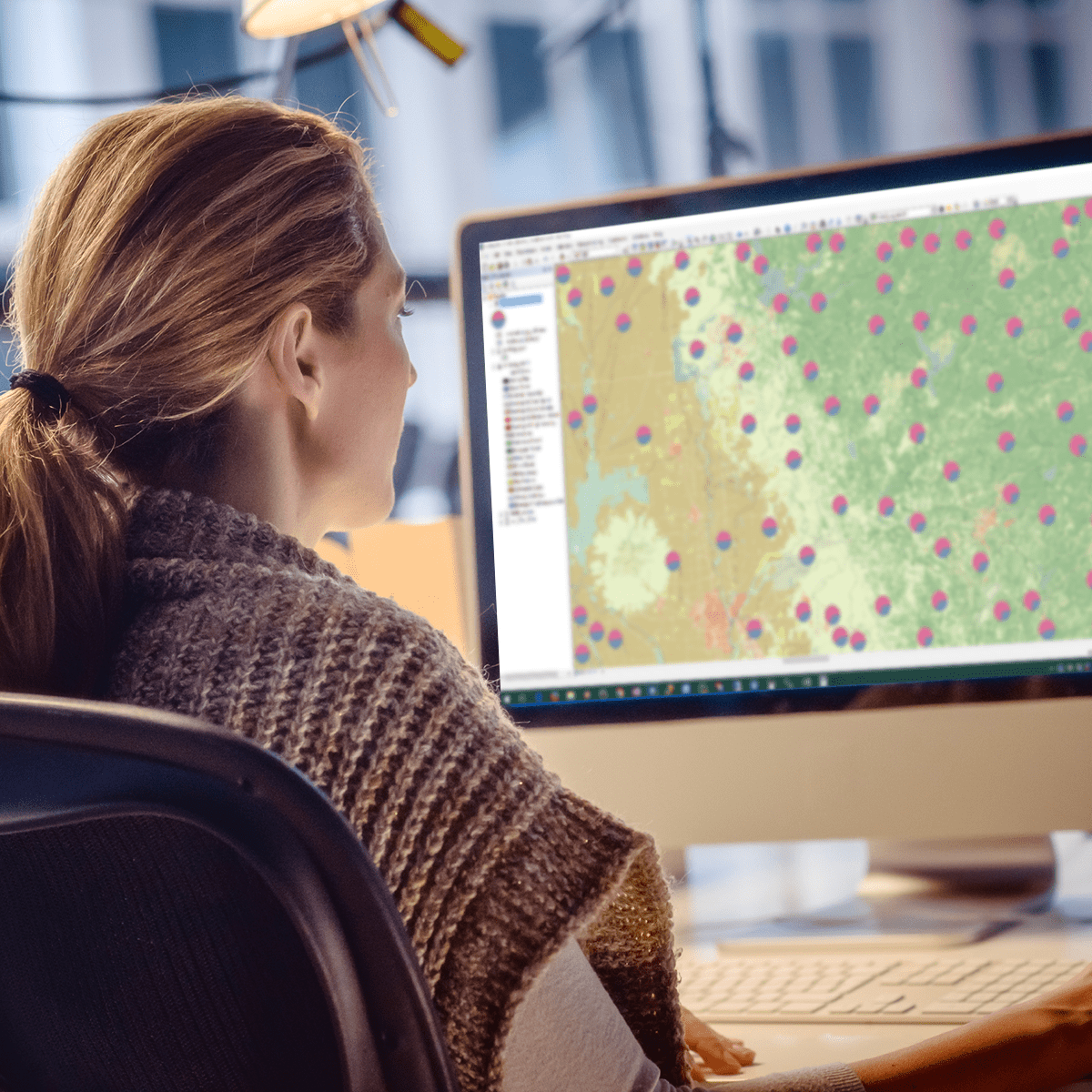

Remote Sensing and GIS Applications

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and remote sensing technologies provide powerful capabilities for spatial analysis and data visualization in water resources management. GIS is used to manage, analyze, and map geographic data related to watersheds, infrastructure, land use, soil types, and water quality monitoring sites.

Remote sensing, using data from satellites or aircraft, allows for monitoring environmental conditions over large areas. Applications include mapping flood inundation, assessing vegetation health (related to drought stress), monitoring snowpack, estimating evapotranspiration, and detecting changes in water bodies or land cover over time. Tools like Google Earth Engine provide cloud-based platforms for large-scale geospatial analysis.

Expertise in GIS software (like ArcGIS or QGIS) and remote sensing techniques enables managers to better understand spatial patterns, assess environmental conditions, and communicate information effectively through maps and visualizations.

These courses offer training in relevant GIS and remote sensing tools.

Data Analytics in Water Demand Forecasting

Accurate water demand forecasting is critical for effective planning and operation of water supply systems. Traditional forecasting methods are being enhanced by modern data analytics techniques. Statistical analysis, time series modeling, and machine learning algorithms can analyze historical consumption data, weather patterns, demographic trends, and economic factors to produce more accurate short-term and long-term demand predictions.

Improved forecasts help optimize water treatment and distribution, plan infrastructure investments more effectively, and design targeted conservation programs. Managers increasingly need skills in data management, statistical analysis, and potentially programming languages like R or Python used in data science to leverage these analytical tools.

Understanding statistical methods applied to water resources is fundamental.

Emerging AI-Driven Solutions

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are beginning to offer innovative solutions across various aspects of water management. AI can be used to optimize the operation of water treatment plants, predict equipment failures in distribution networks, improve the accuracy of flood or drought forecasts, and analyze complex datasets to identify patterns related to water quality or consumption.

While still an emerging area, AI holds potential for enhancing efficiency, improving predictive capabilities, and supporting more sophisticated decision-making. Water professionals who understand the potential applications and limitations of AI/ML will be well-positioned to leverage these technologies as they mature. Familiarity with data science principles provides a good foundation.

Explore related fields on OpenCourser through the Data Science category.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is a graduate degree mandatory for this career?

A graduate degree (Master's or Ph.D.) is not strictly mandatory for all positions, but it is often preferred or required for more specialized, research-oriented, or senior management roles. A bachelor's degree in a relevant field like environmental science, civil engineering, or hydrology is typically the minimum requirement for entry-level positions. However, an advanced degree provides deeper expertise and can significantly enhance competitiveness and career advancement opportunities, particularly in policy, research, and specialized consulting.

How competitive is the job market?

The job market competitiveness can vary depending on geographic location, specific specialization, and economic conditions. However, the overall outlook is generally positive. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), employment for environmental scientists and specialists (a category that includes many water resource professionals) is projected to grow about as fast as the average for all occupations. Growing awareness of water scarcity, climate change impacts, and environmental regulations drives demand for qualified professionals. Candidates with strong technical skills, practical experience (internships), and advanced degrees or certifications often have a competitive edge.

Can this role transition to other sustainability fields?

Yes, the skills and knowledge gained as a Water Resources Manager are highly transferable to broader sustainability roles. Water is a core element of environmental sustainability, and experience in managing this resource provides a strong foundation for addressing other environmental challenges. Potential transition areas include corporate sustainability management, climate change adaptation planning, renewable energy development, environmental policy analysis, or sustainable agriculture. The interdisciplinary nature of water management, involving science, engineering, policy, and economics, equips professionals with a holistic perspective valuable across the sustainability sector.

What soft skills are most valued?

Beyond technical expertise, several soft skills are crucial for success. Strong communication skills (both written and verbal) are essential for writing reports, presenting findings, and engaging with diverse stakeholders. Collaboration and teamwork are vital, as managers work closely with scientists, engineers, policymakers, and the public. Problem-solving and critical thinking are needed to address complex water challenges. Negotiation and conflict resolution skills are important for mediating competing water demands. Leadership and project management abilities become increasingly important for career advancement.

Impact of automation on the profession?

Automation and technology are changing aspects of the profession but are unlikely to replace the core functions of Water Resources Managers entirely. Automation can enhance efficiency in data collection (sensors), monitoring (remote sensing), and routine analysis. AI may improve modeling and forecasting. However, the role requires critical thinking, judgment, stakeholder engagement, policy interpretation, and strategic planning – tasks that are difficult to fully automate. Professionals will need to adapt by learning to use new technologies effectively, focusing on higher-level analysis, interpretation, and decision-making rather than routine data processing.

Global demand for water resources professionals?

There is significant global demand for water resources professionals. Water scarcity, pollution, and the impacts of climate change are global challenges affecting nearly every country. Developing nations often face critical needs for expertise in building water infrastructure, improving sanitation, and establishing sustainable management practices. International organizations, development banks, NGOs, and consulting firms actively recruit professionals for projects worldwide. Expertise in transboundary water issues, climate adaptation, and integrated water resources management is particularly valuable in the international arena.

Embarking on a career as a Water Resources Manager is a challenging yet deeply rewarding path. It offers the opportunity to apply scientific and technical knowledge to solve critical real-world problems, contributing directly to environmental health and human well-being. While the journey requires dedication to continuous learning and navigating complex issues, the chance to ensure the sustainable management of our most precious resource makes it a vital and fulfilling profession for those passionate about water and the environment.