Building Inspector

Building Inspector: A Comprehensive Career Guide

Building inspectors play a crucial role in ensuring the safety and integrity of the structures where we live, work, and gather. They are the professionals responsible for examining buildings during various stages of construction and remodeling, as well as existing structures, to verify compliance with local and national building codes, ordinances, and regulations.

Working as a building inspector involves a unique blend of technical knowledge, attention to detail, and communication skills. It offers the satisfaction of contributing directly to public safety and community well-being. For those interested in construction, architecture, and regulation, this field provides a dynamic and essential career path.

What is a Building Inspector?

Defining the Role and Its Purpose

A building inspector is fundamentally a guardian of public safety within the built environment. Their core purpose is to enforce building codes and standards designed to protect occupants from hazards like structural failure, fire, improper electrical wiring, or unsanitary plumbing. They achieve this through systematic inspections at different project phases.

Inspectors review plans, visit construction sites, and meticulously check workmanship and materials. They look for compliance with zoning regulations, contract specifications, and established safety standards. If violations are found, they issue notices and may halt work until corrections are made, ensuring that structures are sound, safe, and legally compliant.

This role requires a deep understanding of construction processes, materials, and the complex web of regulations governing them. Inspectors act as an impartial authority, mediating between builders, owners, and regulatory bodies to uphold standards.

For those interested in the technical aspects of how buildings come together, these courses offer foundational knowledge.

A Brief History of Building Inspection

The concept of ensuring building safety dates back centuries, with early examples like the Code of Hammurabi mentioning consequences for builders whose structures collapsed. However, modern building inspection as a formal profession evolved significantly with urbanization and industrialization, particularly after major urban fires like the Great Fire of London (1666) and the Great Chicago Fire (1871).

These events highlighted the catastrophic potential of unregulated construction and led to the development of more comprehensive building codes. The early 20th century saw the formation of organizations dedicated to standardizing codes, such as predecessors to the modern International Code Council (ICC). This standardization paved the way for the professionalization of building inspection.

Technological advancements in materials and construction methods continuously shape the role, requiring inspectors to stay updated on new challenges and regulations. The focus has expanded beyond basic structural safety to include energy efficiency, accessibility, and environmental sustainability.

Where Building Inspectors Work

Building inspectors are employed across various sectors, primarily within government agencies. Municipal, county, and state governments hire inspectors to enforce local building codes and zoning laws for residential, commercial, and industrial properties within their jurisdictions.

Beyond government roles, some inspectors work for private inspection companies, often contracted by lenders, insurance companies, or prospective homebuyers to assess property conditions. Others might work directly for large construction firms or developers in quality control roles, ensuring internal standards are met before official inspections occur.

Specialized inspectors might focus on specific areas like electrical systems, plumbing, mechanical systems (HVAC), or fire safety. Opportunities exist in diverse settings, from bustling urban centers overseeing high-rise construction to rural areas inspecting residential homes and agricultural structures.

Understanding the broader context of construction management can be beneficial.

Day-to-Day Life of a Building Inspector

Core Responsibilities and Tasks

The daily routine of a building inspector often involves a mix of fieldwork and office tasks. A significant portion of the day is spent on-site, conducting inspections at various construction phases, from foundation work to final walkthroughs. This requires navigating active construction sites, climbing ladders, and accessing tight spaces like crawl spaces or attics.

Inspectors meticulously examine structural elements, electrical wiring, plumbing installations, insulation, roofing, and fire protection systems. They compare the ongoing work against approved plans and relevant building codes. Documentation is key; inspectors record their findings, take photographs, and write detailed reports outlining compliance or identifying violations.

Office duties include reviewing construction plans and permit applications before work begins, scheduling inspections, communicating findings to contractors and property owners, and maintaining records. They may also need to research specific code requirements or consult with colleagues or supervisors on complex issues.

Understanding and Enforcing Building Codes

A central part of the job is interpreting and applying a wide array of building codes. These codes cover aspects like structural integrity, fire safety, electrical systems, plumbing, mechanical systems (HVAC), energy efficiency, and accessibility. Inspectors must be proficient in the specific codes adopted by their jurisdiction, which often include model codes like the International Building Code (IBC) or National Electrical Code (NEC), potentially with local amendments.

Enforcement involves identifying deviations from these codes during inspections. When non-compliance is found, inspectors must clearly communicate the issue to the responsible parties (contractors, owners) and specify the required corrective actions. This often requires diplomacy and clear explanation of technical requirements.

These book resources provide comprehensive guides to major building codes.

Inspectors may issue stop-work orders for serious violations until issues are resolved. They conduct follow-up inspections to verify that corrections have been made properly before allowing construction to proceed or issuing certificates of occupancy.

These courses cover specific code areas like fire safety and plumbing.

Collaboration and Communication

Building inspectors rarely work in isolation. Effective communication and collaboration are essential. They interact daily with architects, engineers, contractors, construction workers, property owners, and other government officials (like zoning officers or fire marshals).

Clear communication is needed to explain code requirements, detail violations, and discuss solutions. Inspectors must be able to translate technical jargon into understandable terms for non-experts. They also need strong negotiation and conflict resolution skills when disagreements arise regarding code interpretations or required corrections.

Building positive working relationships based on professionalism and fairness helps facilitate compliance and smoother project progression. Inspectors often serve as a resource, providing guidance on code requirements during the design and planning stages to help prevent issues later in construction.

Becoming a Building Inspector: Education and Training

Formal Education Routes

While requirements vary, a high school diploma or equivalent is typically the minimum educational prerequisite. Post-secondary education in fields like construction management, architecture, civil engineering technology, or building inspection technology is highly advantageous and increasingly preferred or required by employers.

Associate's degrees or vocational programs specifically focused on building codes and inspection provide targeted training. Courses often cover blueprint reading, construction materials and methods, specific codes (structural, electrical, plumbing, mechanical), and inspection procedures. Some roles, particularly specialized or supervisory positions, may require a bachelor's degree in engineering or architecture.

Understanding construction fundamentals is key. These courses offer insight into structural engineering and building processes.

Look for programs accredited by relevant bodies to ensure quality education that aligns with industry standards and certification requirements.

Certification and Licensing

Certification is often mandatory for building inspectors, especially those working for government agencies. Requirements differ significantly by state and municipality. The International Code Council (ICC) is the most widely recognized organization offering certifications for various inspection specialties (e.g., Residential Building Inspector, Commercial Electrical Inspector, Plumbing Inspector, Fire Inspector).

Obtaining ICC certification typically involves passing exams demonstrating knowledge of specific codes and inspection practices. Multiple certifications may be required depending on the scope of the role. Some jurisdictions may have their own state-specific licensing exams and requirements in addition to or instead of ICC certification.

Continuing education is usually necessary to maintain certifications and stay current with code updates and new construction technologies. Prospective inspectors should research the specific requirements for the region where they intend to work early in their career planning.

For those specifically interested in fire safety aspects, related courses can be valuable.

Apprenticeships and On-the-Job Training

Practical experience is crucial in this field. Many aspiring inspectors gain experience through apprenticeships, internships, or entry-level positions like inspection assistants. Working under the supervision of experienced inspectors provides invaluable hands-on training in applying codes, identifying issues, and navigating real-world construction sites.

Some individuals transition into inspection roles after working for several years in a construction trade (e.g., electrician, plumber, carpenter). This trade experience provides a strong practical foundation for understanding construction processes and potential problem areas. Employers often value this hands-on background.

On-the-job training typically involves shadowing senior inspectors, gradually taking on more responsibility, learning local procedures and paperwork, and preparing for certification exams. This blend of practical experience and formal knowledge acquisition is often the most effective path to becoming a fully qualified inspector.

Leveraging Online Learning for a Building Inspection Career

Building Foundational Knowledge Online

Online courses offer a flexible and accessible way to build the foundational knowledge needed for a career in building inspection. Platforms like OpenCourser aggregate courses covering essential topics such as building codes, construction materials science, blueprint reading, structural principles, and specific systems like electrical or plumbing.

These courses can serve as an excellent starting point for individuals exploring the field or preparing for formal education or certification exams. They allow learners to study at their own pace and convenience, fitting education around existing work or personal commitments. Look for courses taught by industry professionals or affiliated with reputable institutions.

Understanding architectural drawing is crucial for inspectors.

For those considering a career change, online learning provides a low-risk way to gauge interest and aptitude for the subject matter before committing to a full degree program or apprenticeship. It demonstrates initiative and a commitment to learning, which potential employers value.

Supplementing Formal Education and Training

Even for those pursuing traditional education or apprenticeships, online courses can be powerful supplements. They can help reinforce concepts learned in class, provide deeper dives into specialized topics not fully covered in a curriculum, or offer refreshers on specific code sections.

Online platforms often feature courses on the latest industry trends, such as green building practices or new construction technologies, helping students and professionals stay current. They can also provide targeted preparation for specific certification exams offered by organizations like the ICC.

Using tools like OpenCourser's "Save to list" feature (manage your list here), learners can curate personalized learning paths, combining formal education with supplementary online resources to create a well-rounded knowledge base.

Explore courses covering structural concepts and specific materials.

Developing Skills Through Virtual Projects

While hands-on site experience is irreplaceable, online learning can incorporate practical elements through virtual projects and case studies. Some courses may involve analyzing digital blueprints, simulating inspections based on provided scenarios, or evaluating case studies of building failures or code violations.

These activities help develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills applicable to real-world inspections. They allow learners to practice applying code knowledge in a controlled environment. Completing such projects can also help build a portfolio demonstrating practical understanding, which can be valuable when seeking entry-level positions or apprenticeships.

Look for courses that include hands-on exercises, quizzes, and project-based assessments to maximize practical skill development alongside theoretical learning. OpenCourser's detailed course pages often outline syllabi and activities, helping learners choose courses with strong practical components.

Courses focusing on specific design software and modeling can also be relevant.

Career Path and Advancement Opportunities

Starting as a Building Inspector

Most individuals enter the field in entry-level roles such as trainee inspector, assistant inspector, or permit technician. These positions typically involve working under the direct supervision of experienced inspectors, learning procedures, assisting with inspections, reviewing basic plans, and handling administrative tasks.

Gaining practical experience and obtaining initial certifications (often within a specified timeframe set by the employer) are key goals during this phase. Building a strong understanding of local codes, construction practices, and communication protocols is essential for advancement.

Networking within the local construction and regulatory community can also be beneficial. Attending industry meetings or joining professional organizations can provide learning opportunities and visibility.

Advancing to Senior and Specialized Roles

With experience and additional certifications, inspectors can advance to roles with greater responsibility. This might involve becoming a certified combination inspector (qualified in multiple disciplines like building, electrical, plumbing, and mechanical) or specializing in a specific area like commercial buildings, fire protection systems, or accessibility compliance.

Senior inspectors often handle more complex projects, mentor junior staff, and may have lead roles on inspection teams. Further advancement can lead to positions like Plans Examiner (reviewing complex blueprints for code compliance before construction), Senior Inspector, or Chief Building Inspector/Official, which involves managing an entire inspection department.

Obtaining advanced certifications, pursuing further education (like a bachelor's degree), and demonstrating strong leadership and technical skills are crucial for moving into these higher-level positions.

Understanding specific structural components is key for specialization.

Pivoting to Related Fields

The skills and knowledge gained as a building inspector open doors to various related career paths. Experienced inspectors might move into roles in construction management, quality control for private developers, or consulting, advising clients on code compliance and building practices.

Some transition into municipal roles focused on code development, zoning administration, or urban planning. Others may leverage their expertise to become educators or trainers for aspiring inspectors or construction professionals. The deep understanding of regulations and construction processes is highly transferable.

Furthermore, inspectors with specialized knowledge in areas like energy efficiency or sustainable building practices might find opportunities in the growing field of green building consulting or certification.

Consider exploring related careers like architectural design.

Key Skills for Success as a Building Inspector

Technical Proficiency

Strong technical skills form the bedrock of a building inspector's competence. This includes the ability to read and interpret complex blueprints, schematics, and construction documents accurately. A thorough understanding of construction methods, materials, and systems (structural, electrical, plumbing, HVAC) is essential.

Inspectors must be proficient in applying building codes and standards correctly in diverse situations. Familiarity with diagnostic tools, such as levels, measuring tapes, circuit testers, and potentially more advanced equipment like thermal cameras or moisture meters, is also necessary.

Continuous learning is vital to keep up with evolving codes, new materials, and innovative construction techniques. Technical proficiency is constantly tested and must be maintained throughout one's career.

These courses help develop technical skills in blueprint reading and understanding building components.

Essential Soft Skills

While technical knowledge is critical, soft skills are equally important for success. Meticulous attention to detail is paramount, as overlooking even minor code violations can have serious consequences. Strong observational skills are needed to identify potential problems during site inspections.

Effective communication, both written and verbal, is crucial for explaining findings clearly and professionally to diverse audiences. Inspectors need good interpersonal skills to build rapport and manage potentially confrontational situations involving code violations or stop-work orders. Problem-solving abilities help in identifying solutions when issues arise.

Integrity and impartiality are non-negotiable traits. Inspectors must enforce codes fairly and consistently, without bias or favoritism. Good time management and organizational skills are needed to handle a busy schedule of inspections and paperwork efficiently.

Adaptability and Continuous Learning

The construction industry is constantly evolving, with new materials, technologies, and building methods emerging regularly. Building codes are also updated periodically to reflect these changes and address new safety concerns. Therefore, adaptability and a commitment to lifelong learning are essential for building inspectors.

Inspectors must be willing to learn about advancements like green building techniques, smart home technology, or innovative structural systems. They need to stay informed about code updates through continuing education courses, industry publications, and professional development opportunities.

Embracing new technologies used in inspection, such as drones for roof inspections or specialized software for reporting, can also enhance efficiency and effectiveness. A proactive approach to learning ensures inspectors remain competent and valuable throughout their careers.

Exploring sustainable building practices is increasingly important.

The Evolving Landscape of Building Inspection

Impact of Green Building and Sustainability

Growing awareness of environmental issues has led to increased emphasis on sustainable or "green" building practices. This trend significantly impacts building inspectors, who must now often enforce codes related to energy efficiency, water conservation, sustainable materials, and indoor air quality.

Inspectors may need specialized knowledge of standards like LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) or local green building ordinances. They inspect features such as high-performance insulation, energy-efficient windows, solar panel installations, rainwater harvesting systems, and the use of low-VOC materials.

This requires continuous learning to understand the technical specifications and inspection protocols for these evolving technologies and standards. The push towards sustainability adds another layer of complexity and responsibility to the inspector's role.

Automation and Technological Advancements

Technology is transforming the field of building inspection. Drones are increasingly used for inspecting hard-to-reach areas like roofs or facades, improving safety and efficiency. Thermal imaging cameras help detect issues like heat loss, moisture intrusion, or electrical hotspots that might not be visible otherwise.

Software applications streamline report writing, scheduling, and record keeping. Building Information Modeling (BIM) provides detailed 3D models that can aid in plan review and inspection verification. Artificial intelligence (AI) is being explored for tasks like automated plan review or identifying potential issues from images.

While technology offers powerful tools, it doesn't replace the need for skilled inspectors. Human judgment, critical thinking, and on-site verification remain essential. Inspectors must adapt by learning to use these new tools effectively to enhance their work.

Urbanization and Infrastructure Challenges

Global trends like rapid urbanization and the aging of infrastructure in many developed countries create ongoing demand for building inspectors. Increased construction activity in growing cities requires more inspections to ensure new buildings meet safety standards.

Simultaneously, older buildings require periodic inspections to assess their structural integrity, fire safety systems, and compliance with current codes, especially during renovations or changes in use. Inspectors play a vital role in ensuring the safety of existing building stock and managing the risks associated with aging infrastructure.

These trends suggest a stable or growing need for qualified building inspectors who can navigate the complexities of both new construction and the maintenance of older structures within evolving urban landscapes.

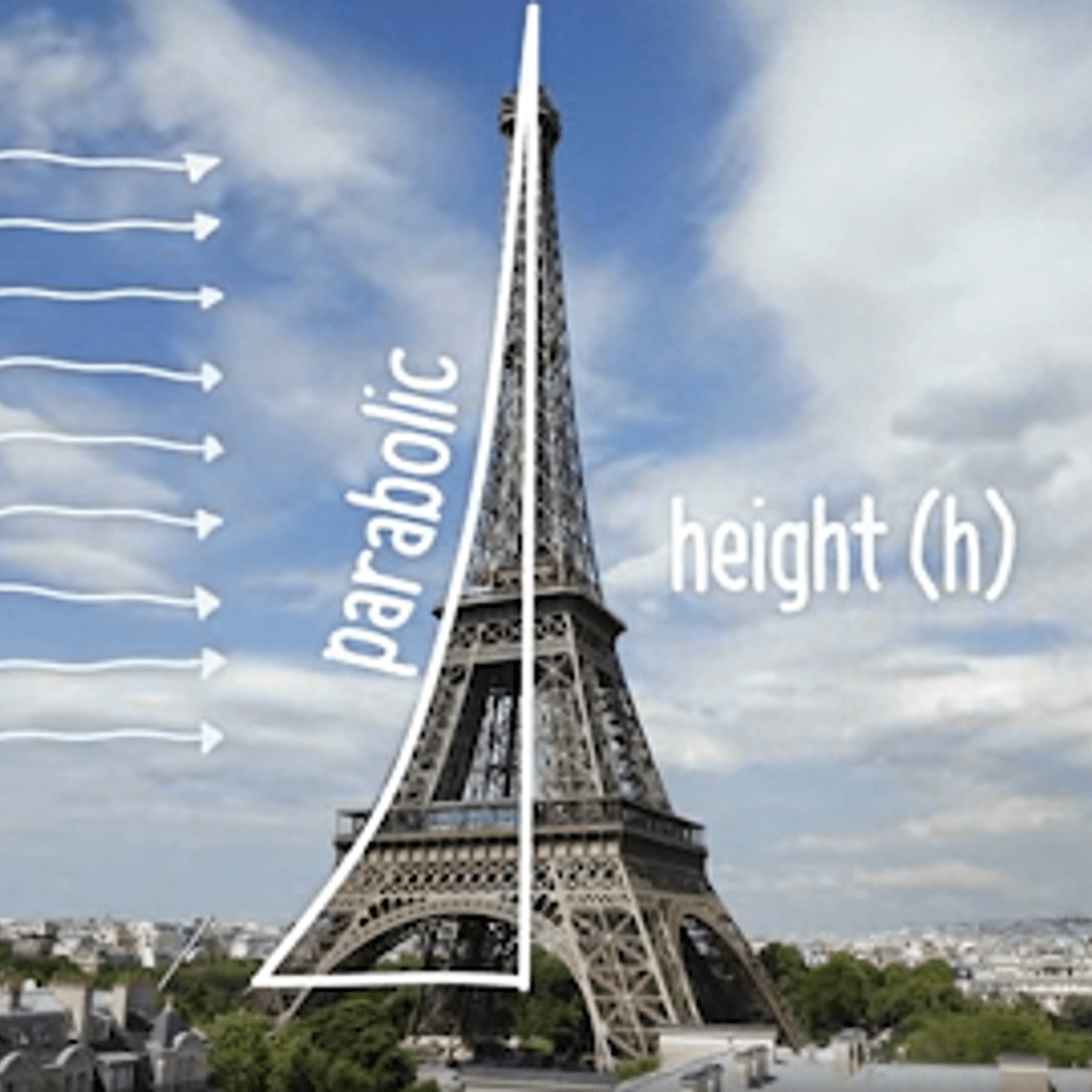

Understanding structural responses, particularly in contexts like seismic activity, is crucial.

Ethical Standards and Safety in Practice

Maintaining Objectivity and Avoiding Conflicts

Ethical conduct is paramount for building inspectors. They must maintain objectivity and impartiality in all their dealings. This means enforcing codes consistently and fairly, regardless of who owns the property or who performed the construction work.

Avoiding conflicts of interest, or even the appearance of conflicts, is crucial. Inspectors should not inspect projects where they have a personal or financial stake, nor should they accept gifts or favors that could compromise their judgment. Upholding public trust requires unwavering integrity.

Professional organizations often have codes of ethics that guide inspectors' conduct. Adherence to these ethical standards is essential for maintaining the credibility and effectiveness of the building inspection profession.

This book provides context on regulation and its challenges.

Legal Responsibilities and Liabilities

Building inspectors carry significant legal responsibilities. Their decisions directly impact property values, project timelines, and, most importantly, public safety. Failure to properly identify code violations or negligence in performing inspections can lead to serious consequences, including property damage, injuries, or fatalities.

Inspectors and their employing agencies can potentially face legal liability if their actions (or inactions) contribute to such negative outcomes. Thorough documentation, adherence to established procedures, and a comprehensive understanding of applicable codes and laws are critical for mitigating legal risks.

Staying informed about legal precedents and liability issues related to building inspection is an important aspect of professional development in this field.

Navigating On-Site Physical Risks

The job of a building inspector inherently involves physical risks. Inspections often take place on active construction sites with potential hazards like falling objects, uneven terrain, heavy machinery, and exposure to dust or chemicals. Inspectors need to be physically fit enough to navigate these environments safely.

Tasks may require climbing ladders or scaffolding, entering confined spaces like attics or crawl spaces, and traversing roofs. Adherence to safety protocols, including wearing appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) like hard hats, safety glasses, and sturdy footwear, is essential.

Awareness of potential site hazards and following established safety procedures are critical for preventing accidents and injuries. Employers typically provide safety training and equipment, but individual vigilance remains key.

Understanding safety procedures, like working at heights, is vital.

Essential Tools and Technologies

Diagnostic and Measurement Equipment

Building inspectors rely on a variety of tools to perform their duties effectively. Basic tools include measuring tapes, levels, flashlights, and cameras for documenting conditions. More specialized diagnostic equipment is often necessary as well.

Moisture meters help detect hidden water intrusion, which can lead to mold or structural damage. Thermal imaging cameras can identify insulation deficiencies, air leaks, moisture problems, or overheating electrical components. Electrical testers are used to verify proper wiring and grounding.

Familiarity with the proper use and interpretation of these tools is a key skill. The specific tools used may vary depending on the type of inspection (e.g., residential vs. commercial) and specialization (e.g., electrical, plumbing).

Understanding specialized systems is often required.

Software for Efficiency and Compliance

Software plays an increasingly important role in modern building inspection. Mobile applications allow inspectors to record findings, take photos, access code information, and generate reports directly from the field, improving efficiency and accuracy.

Scheduling software helps manage inspection appointments, while database systems track permits, inspection histories, and code violations. Some jurisdictions use geographic information systems (GIS) to map permits and inspections visually.

Proficiency with relevant software platforms is becoming a standard requirement. These tools help streamline workflows, improve data management, and ensure consistent documentation, which is crucial for compliance and potential legal scrutiny.

Knowledge of cost estimation software can also be relevant in related fields.

The Rise of BIM and Advanced Modeling

Building Information Modeling (BIM) is transforming the architecture, engineering, and construction industries, and its impact extends to building inspection. BIM provides detailed, data-rich 3D models of buildings that contain information about components, materials, and systems.

Inspectors can use BIM models during plan review to visualize complex designs and identify potential code conflicts more easily. On-site, mobile access to BIM models can help verify that construction matches the approved design specifications. Some advanced applications even allow for automated code checking against BIM models.

While not yet universally adopted for inspection purposes, familiarity with BIM concepts and software is becoming increasingly valuable for inspectors, particularly those working on large or complex commercial projects. It represents a significant shift towards more integrated, data-driven construction and oversight.

These courses introduce BIM concepts and software.

Frequently Asked Questions about Building Inspection Careers

Is being a building inspector physically demanding?

Yes, the role of a building inspector can be physically demanding. It often requires walking extensively on construction sites, climbing ladders and stairs, accessing confined spaces like crawl spaces and attics, and potentially navigating uneven or hazardous terrain. Good physical condition and mobility are generally necessary.

Inspectors may need to work outdoors in various weather conditions. While not typically involving heavy lifting, the job requires stamina and comfort with heights and enclosed areas. Individuals with significant physical limitations might find certain aspects of the job challenging.

However, the level of physical demand can vary based on specialization (e.g., plan review is less physically demanding than field inspection) and the type of structures typically inspected.

How does salary vary for building inspectors?

Salaries for building inspectors vary based on factors like geographic location, level of experience, certifications held, employer (government vs. private), and specialization. Metropolitan areas with higher costs of living generally offer higher salaries.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the median annual wage for construction and building inspectors was $70,860 in May 2023. Entry-level positions typically start lower, while senior inspectors, specialists, or managers can earn significantly more.

Holding multiple certifications (e.g., combination inspector) or specializing in high-demand areas can also positively impact earning potential. Researching salary data specific to your region and desired sector is recommended.

Can inspectors specialize in specific areas?

Yes, specialization is common in building inspection. While some inspectors are generalists (often in smaller municipalities or residential inspection), many specialize in specific areas based on their background, certifications, and interests. Common specializations include:

Structural Inspection: Focusing on foundations, framing, and load-bearing elements. Electrical Inspection: Examining wiring, panels, fixtures, and compliance with the National Electrical Code. Plumbing Inspection: Checking water supply, drainage, waste, and vent systems. Mechanical Inspection: Focusing on HVAC (heating, ventilation, air conditioning) systems. Fire Safety Inspection: Assessing fire alarms, sprinkler systems, egress routes, and fire-resistant construction.

Other niche areas include energy code compliance, accessibility standards (ADA), or inspections of specific building types like historic structures or healthcare facilities. Specialization often requires additional training and certifications but can lead to deeper expertise and potentially higher demand.

What are common misconceptions about the job?

One common misconception is that building inspectors are solely focused on finding faults or trying to impede construction progress. In reality, their primary goal is ensuring safety and code compliance, acting as partners in the construction process to achieve safe, durable buildings.

Another misconception is that the job is purely technical. While technical expertise is crucial, strong communication, negotiation, and problem-solving skills are equally important for effectively interacting with contractors and owners and resolving issues constructively.

Some may also underestimate the complexity of building codes and the continuous learning required to stay current. It's a dynamic field that demands ongoing professional development, not just a static checklist approach.

How stable is a career as a building inspector?

Careers in building inspection are generally considered stable. Because inspections are legally mandated for most construction and renovation projects, there is a consistent need for qualified inspectors, largely independent of short-term economic fluctuations affecting new construction rates.

Government positions, in particular, tend to offer high job security. While the volume of new construction can impact demand in the private sector, the need for inspections of existing buildings, renovations, and compliance checks related to safety and energy codes provides a baseline level of work.

The BLS projects employment for construction and building inspectors to show little or no change from 2022 to 2032, which is slower than the average for all occupations but still indicates steady demand, especially as infrastructure ages and building codes become more complex.

Are there advancement opportunities without an engineering degree?

Yes, significant advancement is possible without a formal engineering degree. While an engineering or architecture degree can be advantageous, particularly for management roles in larger organizations or specialized technical positions, many successful inspectors advance based on experience, certifications, and demonstrated competence.

Starting in an entry-level role, gaining diverse field experience, and diligently pursuing multiple ICC certifications can lead to senior inspector, combination inspector, or plans examiner positions. Leadership skills and a strong understanding of codes and management principles can open doors to supervisory roles like Chief Building Inspector.

Focusing on continuous learning, professional development, and potentially pursuing an associate's degree or specialized certificate programs can create strong pathways for career growth within the field, even without a four-year engineering degree.

Embarking on Your Path

A career as a building inspector offers a unique opportunity to blend technical expertise with a commitment to public safety. It requires diligence, integrity, and a willingness to continuously learn in a dynamic field. While the path involves rigorous training and certification, it provides the satisfaction of ensuring our built environment is safe and sound for everyone.

If you are detail-oriented, enjoy problem-solving, and are interested in the intricacies of construction and regulation, exploring building inspection further could be a rewarding step. Utilize resources like online technical training courses and investigate local requirements to begin your journey.

Making a career transition or starting a new path can feel daunting, but remember that every expert started somewhere. Building foundational knowledge through accessible resources like online courses is a great first milestone. OpenCourser's Learner's Guide offers tips on structuring your self-learning journey and making the most of educational opportunities. Take that first step, explore the possibilities, and build the future you envision.