Computer Technician

Exploring a Career as a Computer Technician

A Computer Technician is a professional responsible for the installation, maintenance, repair, and troubleshooting of computer hardware, software, and network systems. They are the problem-solvers who keep our digital world running smoothly, tackling issues ranging from a malfunctioning printer to complex network configurations. This role often involves direct interaction with users, helping them overcome technical difficulties and ensuring their systems function effectively.

Working as a Computer Technician can be deeply rewarding. You'll constantly encounter new challenges, requiring analytical thinking and hands-on skills to diagnose and fix problems. The satisfaction of restoring a critical system or helping a frustrated user get back online is a significant part of the job's appeal. Furthermore, the field offers continuous learning opportunities as technology evolves, keeping the work dynamic and engaging.

What Does a Computer Technician Do?

The daily life of a Computer Technician involves a diverse range of tasks focused on ensuring computer systems and networks operate correctly. They are integral to almost every industry, providing essential support to keep businesses, schools, hospitals, and individuals connected and productive.

Hardware Installation, Maintenance, and Repair

A core function of a Computer Technician is working with physical computer components. This includes setting up new workstations, installing hardware upgrades like RAM or hard drives, and replacing faulty parts. Technicians diagnose hardware failures using specialized tools and knowledge, identifying whether a problem lies with the motherboard, power supply, or peripheral devices.

Preventive maintenance is also crucial. Technicians perform routine checks, clean internal components to prevent overheating, and update firmware to ensure optimal performance and longevity of the equipment. They need a strong understanding of how different hardware components interact within a system.

Repairing hardware often requires manual dexterity and careful handling of sensitive electronics. This could involve soldering components on a circuit board (though less common now with modular replacement), reseating connections, or meticulously reassembling a laptop after a screen replacement.

These foundational courses provide essential knowledge about computer hardware components, their functions, and basic troubleshooting techniques, which are vital for any aspiring technician.

For those looking to delve deeper into the specifics of computer hardware and repair, these books offer comprehensive guidance.

Software Troubleshooting and System Optimization

Computer Technicians frequently address software-related issues. This involves diagnosing problems caused by operating system errors, software conflicts, malware infections, or incorrect configurations. They use diagnostic tools and techniques to identify the root cause and apply appropriate solutions, such as reinstalling software, removing viruses, or adjusting system settings.

System optimization is another key responsibility. Technicians ensure computers run efficiently by managing startup programs, cleaning up temporary files, defragmenting hard drives (less needed on SSDs), and ensuring drivers are up-to-date. They might also configure operating system settings for better performance or security.

Understanding different operating systems like Microsoft Windows, macOS, and Linux is essential. Technicians need to be proficient in navigating these systems, utilizing their built-in utilities, and resolving common issues specific to each platform.

These courses offer practical training in managing and troubleshooting popular operating systems, a critical skill set for technicians.

Further reading on operating systems and system-level programming can deepen a technician's understanding.

Network Configuration and Security Basics

While not always the primary focus, many Computer Technicians handle basic network tasks. This can include setting up small office/home office (SOHO) networks, configuring routers and Wi-Fi access points, troubleshooting connectivity issues, and assigning IP addresses.

Understanding fundamental networking concepts like TCP/IP, DNS, DHCP, and network cabling (Ethernet) is important. Technicians often need to diagnose why a computer cannot connect to the network or the internet, which involves checking physical connections, IP configurations, and firewall settings.

Basic security practices are also part of the role. Technicians ensure systems have up-to-date antivirus software, configure firewalls, set strong passwords, and educate users on avoiding phishing scams and malware. They play a first-line defense role in protecting systems and data.

This course provides a solid grounding in operating systems and the networking fundamentals crucial for technician roles.

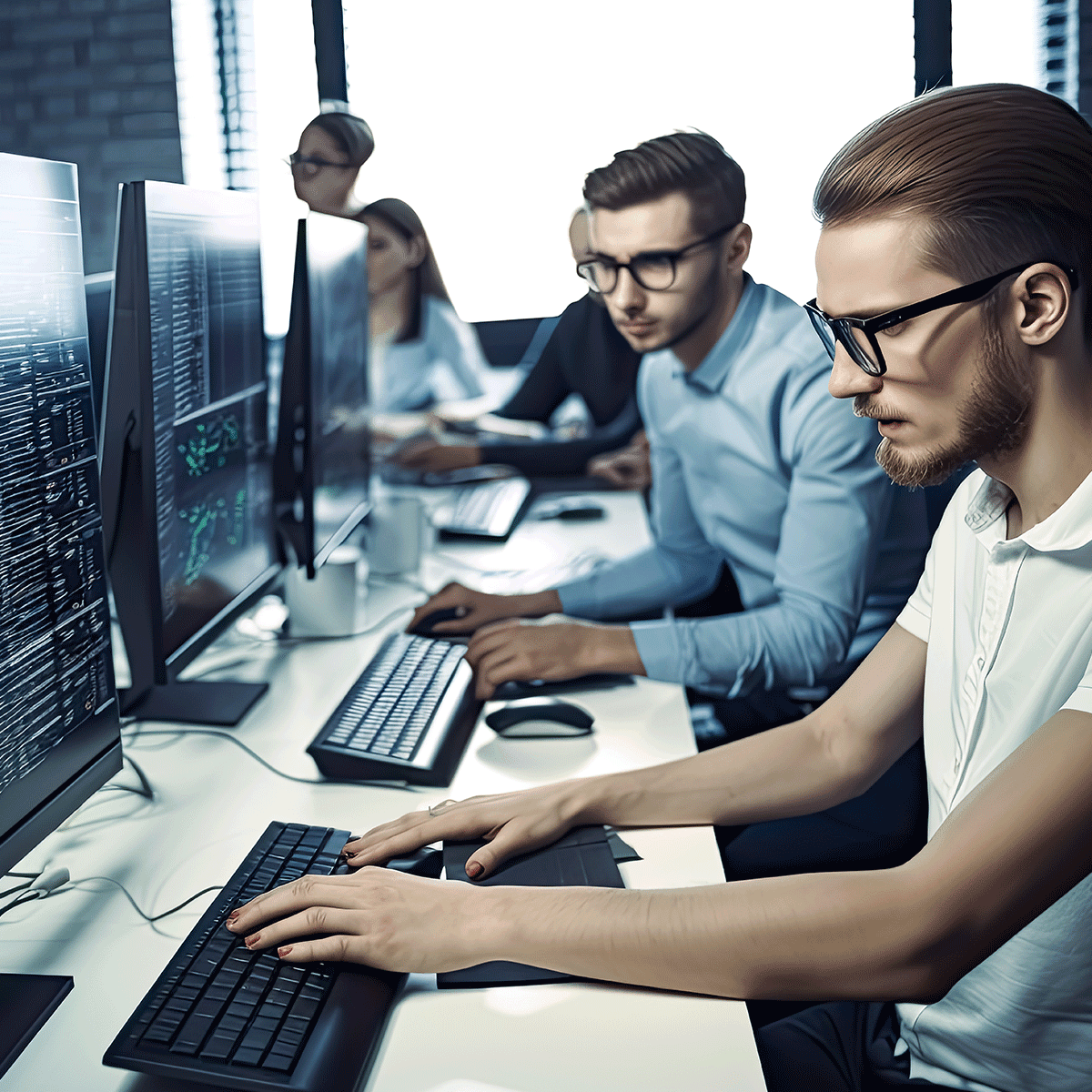

Client/Customer Interaction Expectations

Computer Technicians often interact directly with end-users who may have limited technical knowledge. Therefore, strong communication and interpersonal skills are vital. Technicians must listen patiently to understand the user's problem, explain technical issues in simple terms, and provide clear instructions or updates.

Empathy and patience are key when dealing with frustrated users. The ability to manage expectations, provide reassurance, and maintain a professional demeanor under pressure contributes significantly to success in this role. Good customer service skills can be as important as technical expertise.

Documentation is also part of the interaction. Technicians typically need to log issues, record the steps taken for resolution, and update ticketing systems. Clear and concise documentation helps track recurring problems and assists other team members.

This course focuses specifically on the skills needed for technical support roles, including troubleshooting and customer interaction.

Educational Pathways to Becoming a Computer Technician

Several educational routes can lead to a career as a Computer Technician. The best path depends on individual learning styles, career goals, and available resources. Formal education provides structured learning, while certifications validate specific skills.

High School Preparation and Foundational Knowledge

Aspiring technicians can start building a foundation in high school. Courses in mathematics, physics, computer science, and electronics are beneficial. Engaging in computer clubs, robotics teams, or personal projects like building a computer can provide valuable hands-on experience.

Developing strong problem-solving and logical thinking skills is crucial. Even courses outside of STEM, such as communication or technical writing, can be helpful, given the customer-facing aspects of the job.

Early exposure to basic hardware components and operating systems creates a solid base. Some high schools may even offer introductory IT courses or partnerships with vocational programs that lead to entry-level certifications.

This introductory course covers programming concepts visually, which can be a great starting point for understanding software logic without complex syntax.

Associate vs. Bachelor's Degrees

An Associate Degree in Information Technology, Computer Science, or a related field is a common educational path. These two-year programs typically offer a blend of theoretical knowledge and practical skills in hardware, software, networking, and operating systems, preparing graduates for entry-level technician roles.

A Bachelor's Degree provides a more in-depth and broader education. While often geared towards roles like software development or systems administration, a four-year degree can enhance long-term career prospects, potentially leading to supervisory or specialized technical roles more quickly. It often includes more theory and advanced topics.

The choice between an associate's and bachelor's degree depends on career aspirations and financial considerations. An associate degree offers a faster route into the workforce, while a bachelor's degree may open more doors for advancement later on. Both can be supplemented with industry certifications.

Exploring computer architecture provides a deeper understanding of how computers work at a fundamental level, often covered in degree programs.

Vocational Training and Apprenticeships

Vocational schools and technical colleges offer focused training programs specifically designed for computer technician roles. These programs are often shorter than degree programs (ranging from months to a year or two) and heavily emphasize hands-on skills and preparation for industry certifications.

Apprenticeships, while less common in IT than in traditional trades, offer another pathway. These programs combine on-the-job training with classroom instruction, allowing individuals to earn while they learn practical skills under the guidance of experienced technicians.

These routes can be excellent choices for individuals seeking a quick path to employment and preferring practical, job-focused training over extensive theoretical studies. They often have strong connections with local employers.

Industry-Recognized Certifications (CompTIA A+, Network+)

Industry certifications are highly valued in the IT field, validating specific skills and knowledge recognized by employers worldwide. For Computer Technicians, the CompTIA A+ certification is considered the industry standard for foundational IT skills.

CompTIA A+ covers hardware, software, operating systems, networking, security, and troubleshooting. It typically requires passing two exams. While not always mandatory, holding an A+ certification significantly enhances job prospects for entry-level technicians.

Other relevant certifications include CompTIA Network+ (for networking fundamentals) and CompTIA Security+ (for cybersecurity basics). Vendor-specific certifications (like those from Microsoft or Cisco) can also be valuable depending on the specific job requirements.

These courses are specifically designed to help learners prepare for the CompTIA A+ certification exams, covering the core concepts tested.

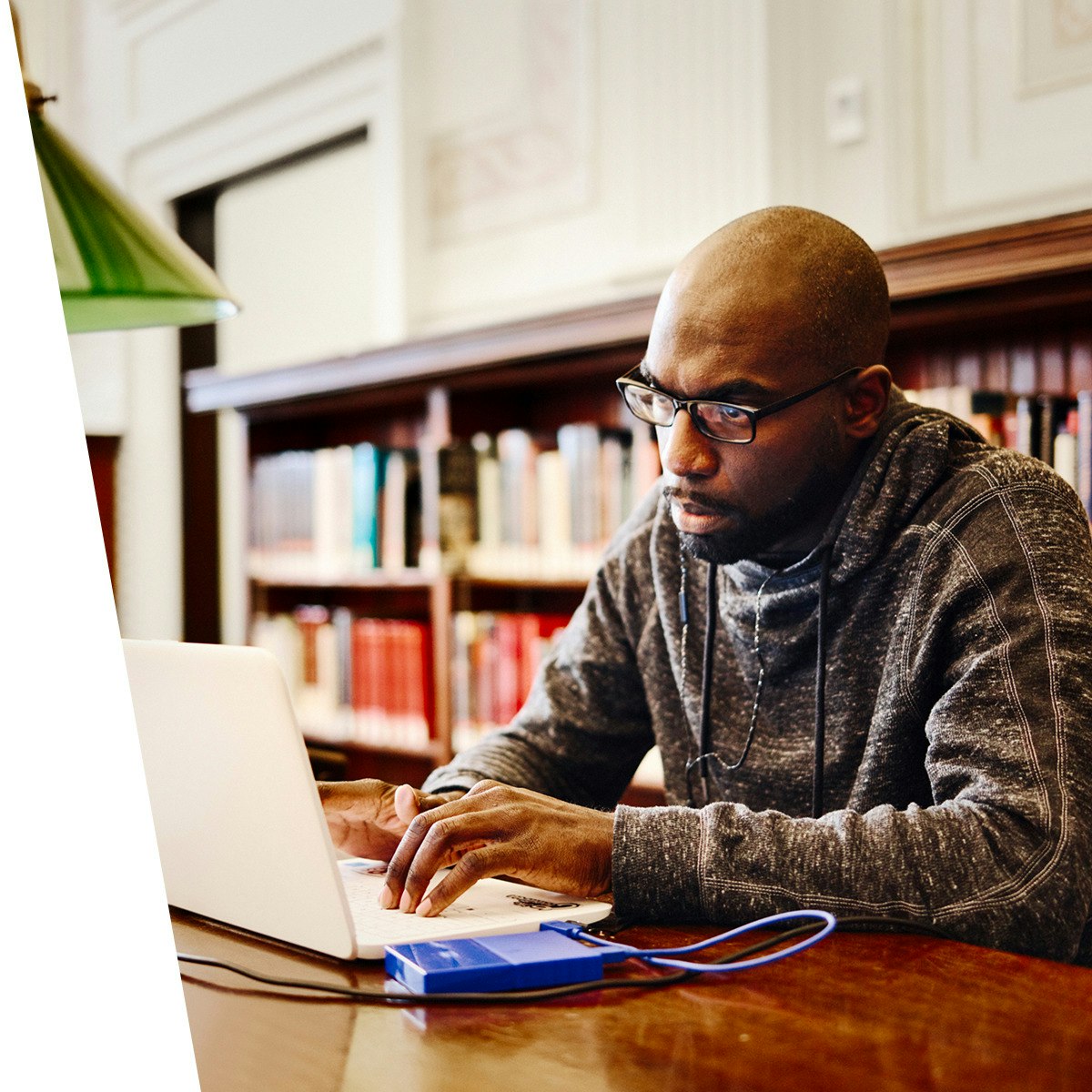

Online Learning and Skill Development

Online learning offers flexible and accessible pathways for acquiring the skills needed to become a Computer Technician. Platforms like OpenCourser provide access to thousands of courses covering hardware, software, networking, and troubleshooting.

Learning Core Technical Skills Remotely

Many fundamental computer technician skills can be effectively learned online. Courses cover topics like computer hardware components, operating system installation and configuration (Windows, macOS, Linux), networking basics, security fundamentals, and software troubleshooting techniques.

Online platforms often use video lectures, interactive simulations, quizzes, and virtual labs to deliver content. This allows learners to study at their own pace and revisit complex topics as needed. Many courses align with industry certifications like CompTIA A+, providing structured preparation.

Self-discipline and motivation are crucial for success in online learning. Setting a schedule, actively participating in forums or communities, and seeking out opportunities for practical application are important strategies.

These courses cover foundational IT topics suitable for online learning, including hardware, operating systems, and troubleshooting principles.

Balancing Theory with Hands-On Practice

While online courses provide excellent theoretical knowledge, computer repair and maintenance require hands-on practice. It's essential to supplement online learning with practical experience. This might involve working on your own computer, disassembling and reassembling old machines, or setting up a home network.

Virtual labs, often included in online courses, can simulate real-world scenarios for software configuration and network troubleshooting. However, they cannot fully replicate the experience of physically handling hardware components.

Seek opportunities to apply learned concepts. Volunteer to help friends or family with computer issues, contribute to open-source projects, or look for internships or volunteer positions that offer practical exposure.

This course specifically focuses on building a simulated network, providing valuable hands-on practice in a virtual environment.

Portfolio-Building with Personal Projects

Creating a portfolio of personal projects demonstrates practical skills and initiative to potential employers. Building a custom PC, setting up a home media server, configuring a virtual machine environment (using tools like VirtualBox or VMware), or creating detailed troubleshooting guides are all valuable portfolio items.

Document your projects thoroughly. Take photos or videos of your hardware builds, write detailed descriptions of the steps involved in setting up a network, and explain the troubleshooting process for resolving specific issues. A well-documented portfolio showcases both technical ability and communication skills.

Platforms like GitHub can host code (if applicable, e.g., simple scripts) and documentation. A personal blog or website can also serve as a platform to showcase your projects and technical knowledge.

Consider projects like building your own computer as excellent hands-on learning experiences.

Limitations of Online-Only Education for Hardware Roles

While online learning is powerful, it has limitations, particularly for roles heavily focused on hardware repair. Diagnosing physical component failures often requires hands-on testing and familiarity with the feel and sound of hardware.

Skills like soldering, delicate component replacement (e.g., laptop screens, mobile device repairs), and using specialized physical diagnostic tools (multimeters, POST cards) are difficult to master solely through online resources. Access to physical equipment and labs is highly beneficial.

Therefore, a hybrid approach, combining online theoretical learning with in-person labs, workshops, or on-the-job training, is often the most effective way to prepare for a comprehensive Computer Technician role that includes significant hardware responsibilities.

Career Progression for Computer Technicians

A role as a Computer Technician often serves as an entry point into the broader IT field. With experience and further training, technicians can advance into various specialized and senior roles.

Entry-Level Positions and Internships

Entry-level roles often involve help desk support, basic hardware setup, software installation, and initial troubleshooting. Titles might include Help Desk Technician, IT Support Specialist (Tier 1), or Junior Computer Technician. Internships provide valuable real-world experience while still studying.

These initial positions focus on developing foundational skills, learning company procedures, and gaining exposure to different technologies. Strong customer service skills are often emphasized at this stage. According to recent data, entry-level salaries typically start around $38,000-$45,000 annually, varying by location and employer.

Building a strong work ethic, demonstrating problem-solving abilities, and pursuing relevant certifications like CompTIA A+ can accelerate progress from these entry points. Using career development resources on OpenCourser can help plan the next steps.

Specialization Paths

After gaining general experience, technicians can specialize in areas like networking, security, server administration, data recovery, or specific operating systems (e.g., Linux administration). Specialization often requires additional certifications (Network+, Security+, CCNA, MCSA) and deeper knowledge.

A Network Technician focuses on installing, configuring, and maintaining network infrastructure. A Data Recovery Specialist works on retrieving lost data from damaged storage devices. A Systems Administrator manages servers, user accounts, and overall system health.

Specialization typically leads to higher earning potential and more complex responsibilities. It allows technicians to focus their skills on areas that align with their interests and market demand.

Transitioning to Senior/Management Roles

Experienced technicians with strong technical and leadership skills can advance to senior roles like Senior IT Technician, IT Team Lead, or IT Support Manager. These positions involve mentoring junior staff, handling complex escalated issues, managing projects, and overseeing support operations.

Moving into management requires developing skills beyond the technical, including project management, budgeting, strategic planning, and personnel management. Further education, like a bachelor's degree or management certifications, can be beneficial.

Senior technical roles might involve designing IT solutions, managing large-scale deployments, or specializing in high-level troubleshooting and system optimization.

Adjacent Career Opportunities

The skills gained as a Computer Technician are transferable to many other IT roles. Technicians might pivot into cybersecurity analysis, database administration, cloud engineering, software development (especially scripting and automation), or IT training.

For example, a strong understanding of hardware and operating systems is valuable for cybersecurity professionals who need to secure endpoints. Networking knowledge can lead to roles in network architecture or telecommunications.

The troubleshooting and problem-solving mindset developed as a technician is a valuable asset across the entire technology sector, providing a solid foundation for diverse career paths.

Tools and Technologies

Computer Technicians rely on a variety of hardware and software tools to perform their jobs effectively. Staying current with industry-standard tools and emerging technologies is essential.

Diagnostic Software and Hardware Tools

Software tools include diagnostic utilities for checking hard drive health (e.g., CrystalDiskInfo), memory testing programs (e.g., MemTest86), network analyzers (Wireshark), malware removal tools, and remote desktop software for providing support.

Hardware tools are essential for physical repairs and diagnostics. These include screwdriver sets (with various bit types like Phillips, Torx, Pentalobe), anti-static wrist straps, multimeters for checking voltages, cable testers for network connections, USB drives with bootable utilities, and sometimes specialized tools for specific devices (like mobile phone opening tools).

Technicians also use software for imaging and deploying operating systems, managing partitions, and securely wiping data from drives.

Current Industry-Standard Operating Systems

Proficiency in major operating systems is fundamental. This includes current versions of Microsoft Windows (e.g., Windows 10, Windows 11) and Windows Server editions for business environments. Familiarity with macOS is necessary for supporting Apple devices.

Knowledge of Linux distributions (like Ubuntu, CentOS, Red Hat) is increasingly valuable, especially in server environments or for specific technical roles. Technicians should understand installation, configuration, user management, command-line interfaces, and troubleshooting for these platforms.

Understanding mobile operating systems like Android and iOS is also important, as technicians often support smartphones and tablets alongside traditional computers.

These courses provide training on popular Windows operating systems, covering essential skills for technicians.

Mastering server operating systems is key for technicians working in business environments.

Emerging Technologies Impacting Repair/Maintenance

Technologies like cloud computing are changing the landscape. While potentially reducing the need for on-premise server maintenance for some businesses, it creates demand for technicians skilled in cloud integration, migration, and supporting cloud-connected devices.

The Internet of Things (IoT) introduces a vast array of connected devices (smart home gadgets, industrial sensors) that may require setup, troubleshooting, and security configurations, expanding the scope of work for technicians.

Automation tools are increasingly used for tasks like software deployment, patch management, and diagnostics. Technicians need to adapt by learning to use and manage these tools effectively, shifting focus towards more complex problem-solving and system optimization.

These courses touch upon cloud technologies that are influencing the IT support field.

Inventory Management Systems

In larger organizations, technicians often use IT asset management (ITAM) or inventory management software. These systems track hardware assets, software licenses, device configurations, and maintenance history.

Proficiency in using these systems is important for maintaining accurate records, managing warranties, planning upgrades, and ensuring software license compliance. Examples include Snipe-IT, ManageEngine AssetExplorer, or modules within larger IT Service Management (ITSM) platforms.

Effective inventory management helps organizations control costs, improve security by knowing what devices are on the network, and streamline the process of deploying and retiring equipment.

Industry Trends and Future Outlook

The field of computer technology is constantly evolving. Understanding current trends and the future outlook helps technicians stay relevant and make informed career decisions.

Impact of Cloud Computing on Local Repair Markets

Cloud computing shifts some infrastructure management from local businesses to large cloud providers (AWS, Azure, Google Cloud). This can reduce the need for on-site server hardware maintenance for some organizations. However, it doesn't eliminate the need for technicians.

Demand shifts towards supporting end-user devices that connect to the cloud, managing cloud service configurations, troubleshooting network connectivity to cloud resources, and assisting with cloud migrations. While the nature of the work changes, the need for skilled support persists. According to some analyses, cloud computing transforms IT roles rather than eliminating them, creating demand for cloud specialists.

Smaller businesses or those with specific security/compliance needs may still rely heavily on local infrastructure, maintaining demand for traditional hardware and server support roles in certain sectors.

Automation in Diagnostics and Labor Implications

Automation tools are increasingly capable of performing routine diagnostics, software updates, and even some basic troubleshooting tasks. This can increase efficiency and potentially handle simpler issues without direct human intervention.

This trend may shift the focus for technicians away from repetitive tasks towards more complex problem-solving, system integration, cybersecurity, and customer-facing advisory roles. Technicians who embrace automation tools and develop higher-level skills are likely to remain in demand.

While automation might affect the number of entry-level positions focused solely on basic tasks, the overall need for skilled IT professionals to manage, configure, and oversee these automated systems, as well as handle issues automation cannot resolve, is expected to remain strong.

Growth of IoT Devices and Expanded Service Opportunities

The proliferation of Internet of Things (IoT) devices—smart thermostats, security cameras, industrial sensors, wearables—creates new opportunities for Computer Technicians. These devices need installation, configuration, network integration, security hardening, and troubleshooting.

Supporting IoT ecosystems requires understanding diverse communication protocols, network configurations, and security vulnerabilities specific to these devices. This represents a growing area where technicians can specialize.

As homes and businesses become increasingly connected, the need for professionals who can manage and maintain these complex environments will likely grow, expanding the traditional scope of a computer technician's work.

Geographic Variations and Employment Demand

Job demand and salary ranges for Computer Technicians can vary significantly based on geographic location, industry concentration, and cost of living. Major metropolitan areas and tech hubs typically offer more opportunities and higher salaries but also have higher living expenses.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) projects overall growth for computer and information technology occupations to be much faster than the average for all occupations through 2032, driven by factors like cloud computing, big data, and cybersecurity. While specific projections for "Computer Technicians" might vary (often grouped under broader categories like "Computer Support Specialists"), the general outlook for IT support roles remains positive. Recent salary data suggests average hourly wages range roughly from $17 to $28, with annual salaries averaging around $43,000-$52,000, though experienced or specialized technicians can earn significantly more.

Remote work opportunities have also increased, potentially broadening the job market beyond local geographic constraints for certain types of technician roles, particularly those focused on software support and remote troubleshooting.

Challenges and Physical Demands

While rewarding, a career as a Computer Technician involves certain challenges and physical demands that potential candidates should consider.

Ergonomic Risks in Repair Work

Technicians often spend long hours sitting or working in potentially awkward positions while repairing computers or installing equipment in tight spaces (like under desks or in server racks). This can lead to repetitive strain injuries (RSIs), back pain, or neck strain if proper ergonomic practices are not followed.

Using ergonomic chairs, maintaining good posture, taking regular breaks, and using appropriate tools can help mitigate these risks. Awareness and proactive measures are important for long-term physical health.

Working with small components can also strain the eyes. Good lighting and occasional breaks to rest the eyes are recommended.

Exposure to Hazardous Materials

While generally safe, technicians may occasionally encounter potentially hazardous materials. Older equipment might contain substances like lead (in solder) or mercury. Batteries, especially lithium-ion batteries found in laptops and mobile devices, can pose fire risks if damaged or handled improperly.

Cleaning chemicals used for equipment maintenance should be handled according to safety guidelines. Proper disposal of electronic waste (e-waste) is also an environmental and potential health consideration.

Following safety protocols, using personal protective equipment (like gloves or safety glasses when appropriate), and receiving proper training on handling specific materials are essential.

Stress Factors in Customer-Facing Troubleshooting

Dealing directly with users experiencing technical problems can be stressful. Users may be frustrated, anxious, or have difficulty explaining the issue. Technicians need patience, empathy, and strong communication skills to manage these interactions effectively.

Time pressure to resolve issues quickly, especially when critical systems are down, can add to the stress. Balancing multiple urgent requests and managing user expectations requires good organizational and time management skills.

Developing coping mechanisms for stress and maintaining a professional, calm demeanor are important aspects of the job, particularly in help desk or direct support roles.

Cybersecurity Responsibilities in Data Handling

Technicians often handle sensitive equipment containing personal or confidential data. They have a significant responsibility to protect this data during repairs, maintenance, or disposal.

Adhering to strict security protocols, ensuring data privacy, and securely wiping storage devices before disposal are critical tasks. Accidental data breaches or improper handling can have serious consequences for both the user/organization and the technician.

Staying informed about cybersecurity best practices, company policies, and relevant regulations (like GDPR or HIPAA) is essential for responsible data handling.

Transferable Skills and Career Pivots

The skills acquired as a Computer Technician are highly transferable, opening doors to various career advancements and pivots within and outside the IT industry.

Troubleshooting Methodologies Across Industries

The core skill of systematic troubleshooting—identifying problems, formulating hypotheses, testing solutions, and verifying fixes—is valuable in almost any field. This logical, analytical approach can be applied to solving problems in engineering, healthcare, finance, logistics, and more.

Technicians become adept at breaking down complex systems into manageable parts to isolate issues. This methodical process is a highly sought-after skill in roles requiring critical thinking and problem-solving.

Documenting troubleshooting steps and solutions also hones analytical writing and process documentation skills, useful in many professional contexts.

Technical Communication Skills Development

Explaining complex technical concepts to non-technical users is a crucial skill developed by Computer Technicians. This ability to translate jargon into understandable language is valuable in roles involving training, sales, technical writing, project management, and customer relations.

Whether writing user guides, providing phone support, or conducting training sessions, technicians learn to adapt their communication style to different audiences. This enhances their overall effectiveness as communicators.

Strong communication skills are essential for collaboration within teams and for effectively conveying technical needs or solutions to management.

Transitioning to IT Training/Education Roles

Experienced technicians with a passion for teaching can transition into IT training or education roles. They can develop and deliver courses on hardware, software, networking, or specific applications for educational institutions, corporate training departments, or certification providers.

Their practical experience provides credibility and allows them to share real-world insights with learners. This path combines technical expertise with instructional and communication skills.

Related roles could include curriculum development, technical writing for educational materials, or becoming a Learning and Development specialist within an organization.

Entrepreneurship Opportunities

Some Computer Technicians leverage their skills and experience to start their own businesses. This could involve offering independent repair services, IT consulting for small businesses, specialized data recovery services, or building and selling custom PCs.

Entrepreneurship requires not only technical skills but also business acumen, including marketing, sales, customer service, and financial management. It offers autonomy but also involves greater risk and responsibility.

Niche markets, such as repairing specific types of equipment (e.g., vintage computers, high-end gaming rigs) or providing specialized support for certain industries, can offer unique entrepreneurial opportunities.

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are answers to some common questions about pursuing a career as a Computer Technician.

Can I become a computer technician without a college degree?

Yes, it is possible to become a Computer Technician without a formal college degree. Many successful technicians rely on industry certifications, vocational training, and hands-on experience. Certifications like CompTIA A+ are highly regarded by employers and validate foundational skills.

While a degree (Associate's or Bachelor's) can be beneficial for long-term advancement or specific roles, practical skills, relevant certifications, and demonstrable experience are often the most critical factors for securing entry-level positions.

Building a strong portfolio of projects and gaining experience through internships or entry-level jobs can effectively demonstrate capability, sometimes outweighing the lack of a formal degree.

How does AI impact computer technician job security?

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and automation are impacting IT, but they are unlikely to eliminate the need for Computer Technicians entirely. AI can assist with diagnostics, automate routine tasks, and provide predictive maintenance insights, potentially increasing efficiency.

However, AI cannot easily replicate the hands-on hardware repair skills, complex problem-solving involving unforeseen variables, or the human interaction often required in customer support. Technicians will likely work alongside AI tools, focusing on tasks requiring physical intervention, critical thinking, and interpersonal skills.

The role may evolve, requiring technicians to learn how to use and manage AI-driven tools, but the fundamental need for human expertise in maintaining and troubleshooting complex systems remains.

What's the difference between computer technicians and IT support specialists?

The terms are often used interchangeably, and roles can overlap significantly. However, "Computer Technician" sometimes implies a stronger focus on hardware repair and maintenance – the physical components of computers.

"IT Support Specialist" might encompass a broader range of responsibilities, including software troubleshooting, network support, user account management, and help desk services, potentially with less emphasis on deep hardware repair.

Ultimately, the specific duties depend on the employer and the job description. Both roles require strong troubleshooting skills and a good understanding of hardware, software, and networking principles.

Is physical strength required for this career?

While not typically requiring heavy lifting, the role can involve some physical demands. Technicians may need to lift and carry computer towers, monitors, or servers (which can be moderately heavy), crawl under desks to access cables, or stand/kneel for extended periods while working on equipment.

Good manual dexterity is important for handling small components and tools. Basic physical fitness is helpful for navigating different work environments and performing installations or repairs.

However, extreme physical strength is generally not a prerequisite, and accommodations can often be made for individuals with physical limitations, especially in roles focused more on software support or remote assistance.

How often do technicians need to update certifications?

Most major IT certifications, including CompTIA A+, Network+, and Security+, require renewal every three years. Renewal typically involves earning Continuing Education Units (CEUs) through activities like attending training, participating in industry events, or passing higher-level certifications.

Alternatively, some certifications allow renewal by passing the latest version of the exam. Keeping certifications current demonstrates a commitment to ongoing learning and staying updated with evolving technologies.

While not all employers strictly require continuous certification renewal after hiring, it is generally a good practice for career development and staying competitive in the job market.

Can this role lead to remote work opportunities?

Yes, remote work opportunities exist for Computer Technicians, particularly for roles focused on software troubleshooting, remote diagnostics, help desk support, and systems administration tasks that don't require physical hardware interaction.

Many organizations now offer remote or hybrid support roles where technicians assist users via phone, chat, or remote desktop software. According to job boards like ZipRecruiter and FlexJobs, numerous remote IT support and technician positions are available.

However, roles involving significant hardware repair, physical network cabling, or on-site equipment installation inherently require a physical presence. The availability of remote work depends heavily on the specific duties and the employer's policies.

Becoming a Computer Technician offers a pathway into the dynamic and ever-evolving world of information technology. It requires a blend of technical knowledge, problem-solving skills, and often, strong communication abilities. With dedication to continuous learning and practical skill development, it can be a rewarding career with numerous avenues for specialization and advancement. Explore the IT & Networking and Tech Skills categories on OpenCourser to find courses that can help you start or advance your journey.