Oncologist

A Comprehensive Guide to a Career as an Oncologist

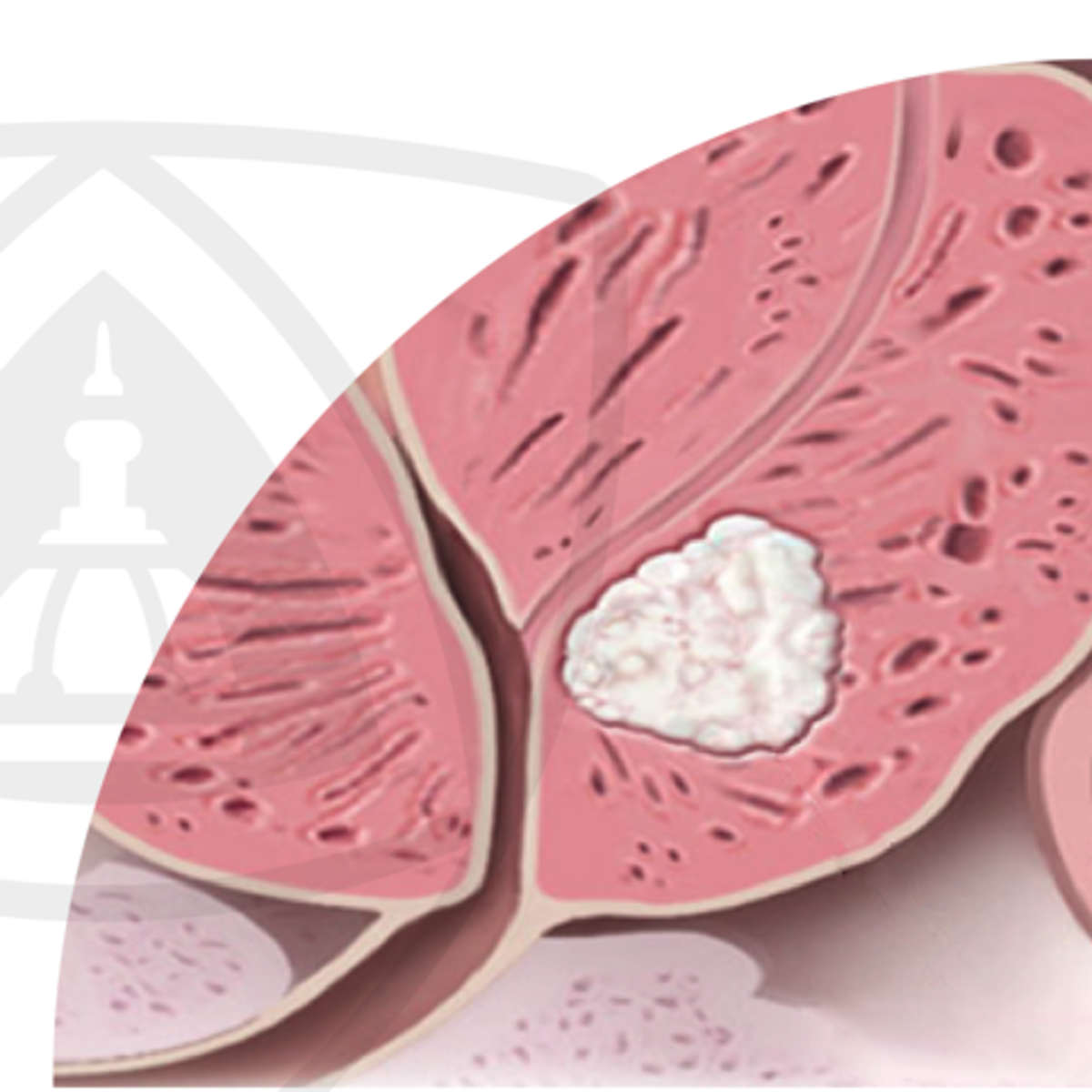

Oncology is the specialized branch of medicine dedicated to the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer. An oncologist is a physician who works within this field, managing the care of patients diagnosed with various forms of cancer throughout their journey with the disease. This involves not only administering treatments but also providing supportive care and coordinating with other healthcare professionals.

Working as an oncologist offers the profound opportunity to make a significant impact on the lives of patients and their families during challenging times. It is a field marked by continuous scientific advancement, offering intellectual stimulation through engagement with cutting-edge research and novel therapies like immunotherapy and targeted treatments. The deep, long-term relationships often formed with patients can also be exceptionally rewarding.

What Does an Oncologist Do? Roles and Responsibilities

Diagnosing Cancer

The path to treating cancer begins with an accurate diagnosis. Oncologists play a crucial role in this process, although they often work closely with pathologists and radiologists. They interpret the results of various diagnostic tests, including biopsies, where tissue samples are examined under a microscope.

They also analyze complex imaging studies such as CT scans, MRI scans, and PET scans to determine the location, size, and extent (stage) of the cancer. Increasingly, molecular and genetic testing of tumors informs diagnosis and guides treatment decisions, moving the field towards personalized medicine.

Understanding the fundamental biology of how cancer develops and spreads is essential. Online courses can provide a solid introduction to these complex topics.

These courses offer foundational knowledge about the mechanisms driving cancer, suitable for those beginning their exploration of the field.

Developing and Overseeing Treatment Plans

Once a diagnosis is confirmed, the oncologist designs a comprehensive treatment strategy tailored to the individual patient's specific type of cancer, stage, overall health, and preferences. This involves selecting and managing various treatment modalities, often in combination.

Common treatments include chemotherapy (using drugs to kill cancer cells), radiation therapy (using high-energy rays), immunotherapy (boosting the body's immune system to fight cancer), targeted therapy (drugs targeting specific molecular changes in cancer cells), and hormone therapy (for hormone-sensitive cancers).

Oncologists monitor patients closely during treatment, managing side effects and adjusting the plan as needed based on treatment response and patient tolerance. This requires a deep understanding of pharmacology, radiation physics, and human physiology.

For those interested in the specifics of cancer treatment and related biological processes, these resources offer valuable insights.

Coordinating Patient Care and Providing Support

Cancer care is inherently multidisciplinary. Oncologists act as the central coordinator for a patient's care team, which may include surgeons, radiologists, pathologists, palliative care specialists, nurses, social workers, nutritionists, and physical therapists. Effective communication and collaboration are vital.

Beyond medical treatments, oncologists provide crucial emotional support and guidance to patients and their families. This involves discussing prognoses, explaining complex medical information clearly, managing expectations, and addressing anxieties and fears related to the diagnosis and treatment.

Ethical considerations are paramount, particularly in discussions around treatment goals, clinical trial participation, and end-of-life care preferences. Oncologists must navigate these sensitive conversations with empathy, honesty, and respect for patient autonomy.

Courses focusing on patient communication and the psychosocial aspects of care can be beneficial.

This course explores the role of mindfulness, which can be a helpful tool for both patients coping with cancer and clinicians managing stress.

The Long Road: Education and Training Requirements

Undergraduate Studies and Pre-Medical Preparation

The journey to becoming an oncologist begins with a bachelor's degree. While any major can be pursued, completing pre-medical coursework is essential. This typically includes foundational courses in biology, general chemistry, organic chemistry, physics, and mathematics.

Aspiring physicians must achieve a strong academic record (GPA) and perform well on the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT). Meaningful extracurricular activities, such as clinical volunteering, research experience, and leadership roles, are also important components of a competitive medical school application.

Building a strong foundation in the sciences is critical during this stage. You can supplement your university coursework or refresh your knowledge using online resources available through platforms like OpenCourser, which aggregates courses from various providers.

Medical School: The Foundation of Medical Knowledge

Medical school is typically a four-year program. The first two years usually focus on foundational medical sciences, covering subjects like anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, pharmacology, pathology, and microbiology. The curriculum often incorporates early clinical exposure.

The latter two years are dedicated to clinical rotations, where students gain hands-on experience in various medical specialties, including internal medicine, surgery, pediatrics, psychiatry, and obstetrics/gynecology. This period helps students explore different fields and develop basic clinical skills.

During medical school, students interested in oncology may seek out elective rotations or research opportunities in the field to gain more exposure and strengthen their residency applications.

Residency in Internal Medicine

After graduating from medical school with an M.D. or D.O. degree, physicians must complete a residency program. To specialize in most types of oncology (like medical oncology or hematology-oncology), a residency in internal medicine is typically required. This is usually a three-year program.

Internal medicine residency provides broad training in the diagnosis and management of adult diseases, offering a strong foundation for subsequent specialization. Residents develop skills in patient management, diagnostic reasoning, and procedural techniques under supervision.

Performance during residency is critical for matching into a competitive oncology fellowship program. Strong clinical skills, positive evaluations, and often, research involvement are key factors.

Standard textbooks are essential during residency. These provide comprehensive coverage of internal medicine principles.

Fellowship: Specializing in Oncology

Following internal medicine residency, physicians pursue a fellowship in their chosen oncology subspecialty. Common pathways include Medical Oncology, Hematology (often combined with Medical Oncology), Radiation Oncology, and Surgical Oncology (which follows a surgical residency). Gynecologic Oncology follows an OB/GYN residency.

Fellowships typically last two to three years (or more for combined programs or research-focused tracks). This period involves intensive, specialized training in managing cancer patients, conducting research, and mastering the specific techniques of the subspecialty (e.g., chemotherapy administration, radiation planning, complex cancer surgery).

Matching into an oncology fellowship program is highly competitive, requiring strong academic credentials, research experience, letters of recommendation, and a demonstrated commitment to the field. This long and demanding educational path requires significant dedication and resilience.

Skills That Define a Successful Oncologist

Mastery of Clinical Knowledge

A deep and continuously updated understanding of cancer biology, genetics, pharmacology, and treatment protocols is fundamental. Oncology is a rapidly evolving field, requiring a commitment to lifelong learning to stay abreast of new diagnostic tools, therapies, and research findings.

This involves regularly reading scientific literature, attending conferences, and potentially participating in clinical trials or research. Clinical expertise forms the bedrock upon which effective patient care is built.

These courses delve into specific areas relevant to modern oncology practice, such as immunology and the molecular basis of cancer.

These books offer in-depth exploration of the molecular aspects of cancer.

Exceptional Communication and Interpersonal Skills

Oncologists must communicate complex, often sensitive information to patients and families in an understandable and empathetic manner. This includes explaining diagnoses, treatment options, potential side effects, and prognoses, including delivering difficult news.

Active listening skills are crucial for understanding patient concerns, values, and preferences, enabling shared decision-making. Effective communication also extends to collaborating seamlessly with the multidisciplinary care team, ensuring coordinated and efficient patient management.

Building trust and rapport with patients facing life-threatening illness is a core aspect of the role. This requires patience, compassion, and cultural sensitivity.

Strong Analytical and Problem-Solving Abilities

Oncologists constantly analyze complex data, including patient histories, physical exam findings, laboratory results, imaging studies, and pathology reports. They must synthesize this information to arrive at accurate diagnoses and develop individualized treatment plans.

Critical thinking is essential for evaluating the risks and benefits of different treatment options, interpreting clinical trial data, and adapting treatment strategies based on patient response and evolving clinical situations.

This analytical rigor extends to research, where oncologists may design studies, analyze data, and contribute to the advancement of cancer knowledge.

Resilience and Emotional Fortitude

Working in oncology involves regular exposure to patient suffering, difficult prognoses, and loss. Oncologists need significant emotional resilience to cope with the inherent stresses of the field while maintaining empathy and providing compassionate care.

Developing coping mechanisms, seeking peer support, and maintaining boundaries between professional and personal life are important for preventing burnout and sustaining a long-term career in this demanding specialty.

Despite the challenges, the ability to help patients navigate their cancer journey and potentially achieve positive outcomes provides immense professional satisfaction and purpose.

Career Paths, Advancement, and Specialization

Diverse Sub-specialties within Oncology

Oncology offers numerous sub-specialization opportunities, allowing physicians to focus on specific types of cancer or patient populations. Medical oncologists primarily use systemic therapies like chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Radiation oncologists specialize in using radiation to treat cancer.

Surgical oncologists are surgeons with additional training in removing cancerous tumors. Other subspecialties include pediatric oncology (treating childhood cancers), gynecologic oncology (treating cancers of the female reproductive system), and hematology-oncology (treating blood cancers like leukemia and lymphoma, as well as solid tumors).

This specialization allows for deeper expertise and focused research within a particular area of cancer care. Exploring specific cancer types through targeted courses can provide insight into these sub-specialties.

These courses focus on specific cancer types or related areas, illustrating the depth available within sub-specialties.

Academic versus Clinical Practice Settings

Oncologists can pursue careers in various settings. Academic medical centers typically involve a combination of clinical patient care, teaching medical students and trainees, and conducting clinical or laboratory research. This path often appeals to those passionate about advancing the field and educating the next generation.

Alternatively, many oncologists work in community hospitals or private practice settings. These roles are often more focused on direct patient care, providing essential cancer services within local communities. The balance between clinical work, research, and teaching varies significantly based on the practice environment.

Some oncologists may also work in the pharmaceutical industry, contributing to drug development and clinical trials, or in public health organizations, focusing on cancer prevention and policy.

Leadership and Advancement Opportunities

With experience, oncologists can advance into leadership positions. Within hospitals or academic centers, opportunities include becoming a Division Chief, Department Chair, Cancer Center Director, or leading specific clinical programs or research initiatives.

Experienced oncologists may also take on leadership roles in national professional organizations, shaping clinical guidelines and advocating for cancer policy. Others may become principal investigators, leading major clinical trials that test new treatments.

Career progression often depends on clinical expertise, research productivity, administrative skills, and leadership qualities. Mentorship and continued professional development play key roles in achieving these advanced positions.

Navigating Ethical Complexities in Cancer Care

Informed Consent and Clinical Trials

Ensuring truly informed consent is a critical ethical duty, especially when discussing complex treatments or participation in clinical trials with experimental therapies. Oncologists must clearly explain the potential benefits, risks, alternatives, and uncertainties involved, ensuring patients understand their choices without coercion.

Balancing the potential for therapeutic benefit with the risks of toxicity or unproven efficacy requires careful judgment and transparent communication. This is particularly complex in early-phase trials where the primary goal may be assessing safety rather than cure.

Respect for patient autonomy means supporting the patient's decision, even if it differs from the physician's recommendation, provided the patient has the capacity to make that decision.

Balancing Hope and Reality

Communicating prognosis in oncology is often challenging. Oncologists must balance providing realistic information about the likely course of the disease with maintaining hope for the patient. Delivering bad news requires sensitivity, empathy, and clarity.

Discussions about goals of care are essential, particularly as the disease progresses. This involves exploring whether the focus should be on curative intent, prolonging life, or maximizing quality of life through palliative measures. These conversations should be ongoing and adapt to changes in the patient's condition and preferences.

Understanding cultural and personal beliefs about illness, death, and dying is vital for providing patient-centered care during these difficult discussions.

End-of-Life Care and Palliative Support

Integrating palliative care early in the course of advanced cancer is increasingly recognized as crucial for managing symptoms, improving quality of life, and supporting patients and families. Oncologists work closely with palliative care teams to address pain, nausea, fatigue, anxiety, and other distressing symptoms.

Discussions about advance care planning, including living wills and designation of healthcare proxies, empower patients to articulate their wishes for future care. Hospice care provides specialized support focused on comfort and dignity for patients nearing the end of life.

Ethical dilemmas can arise regarding the appropriateness of continuing or withdrawing life-sustaining treatments. These decisions require careful consideration of the patient's wishes, medical futility, and the potential burdens versus benefits of interventions.

Industry Trends Shaping the Future of Oncology

The Rise of Precision Medicine and Immunotherapy

Precision medicine, which involves tailoring treatment based on the specific genetic or molecular characteristics of a patient's tumor, is revolutionizing cancer care. Genomic sequencing helps identify targetable mutations, leading to the development of highly effective targeted therapies.

Immunotherapy, which activates the patient's own immune system to attack cancer cells, has produced remarkable results in various cancer types and continues to be a major area of research and development. Understanding immunology is becoming increasingly vital for oncologists.

These advancements require oncologists to continually update their knowledge of molecular biology, genetics, and immunology to effectively apply these sophisticated treatments.

These courses provide insights into the biological underpinnings of modern cancer therapies.

Artificial Intelligence in Diagnosis and Treatment

Artificial intelligence (AI) is emerging as a powerful tool in oncology. AI algorithms are being developed to assist in interpreting medical images (like pathology slides and radiographs) with greater speed and accuracy, potentially improving early cancer detection.

AI can also analyze large datasets (including genomic data, clinical trial results, and real-world evidence) to help predict treatment responses, identify optimal therapeutic strategies, and even accelerate drug discovery.

While AI is unlikely to replace oncologists, it promises to augment their capabilities, improve efficiency, and personalize treatment decisions. Familiarity with data science principles and AI applications in healthcare may become increasingly important for future oncologists.

You can explore foundational concepts in related fields through Data Science or Artificial Intelligence courses on OpenCourser.

Addressing Global Disparities in Cancer Care

Significant disparities exist in cancer incidence, mortality, and access to care across different regions and socioeconomic groups worldwide. Factors contributing to these disparities include lack of access to screening and early detection, limited availability of diagnostic tools and treatments (especially newer, expensive therapies), and shortages of trained oncology professionals.

Efforts are underway by organizations like the World Health Organization and various NGOs to improve cancer control in low- and middle-income countries. This includes initiatives focused on prevention (e.g., HPV vaccination, tobacco control), building healthcare infrastructure, and training local healthcare workers.

Tele-oncology and international collaborations offer potential avenues to expand access to expert consultation and care in underserved regions, though challenges related to technology and regulation remain.

This course explores alternative and integrative approaches, highlighting diverse global perspectives on cancer care.

The Human Side: Challenges and Rewards

Navigating Emotional Intensity and Burnout

The practice of oncology carries a significant emotional weight. Regularly dealing with serious illness, treatment toxicity, and patient deaths can take a toll on physicians' well-being. The demanding nature of the work, including long hours and complex decision-making, contributes to a risk of burnout.

Developing strategies for self-care, stress management, and maintaining a healthy work-life balance is essential for long-term sustainability in the field. Peer support networks and institutional wellness programs can provide valuable resources.

Acknowledging the emotional challenges and seeking support when needed are signs of strength, not weakness, and are crucial for providing optimal patient care over the long haul.

Intellectual Stimulation and Scientific Advancement

Oncology is one of the most dynamic and intellectually stimulating fields in medicine. The rapid pace of research discovery, from understanding fundamental cancer biology to developing novel therapies, offers constant learning opportunities.

Many oncologists are actively involved in research, whether conducting clinical trials, participating in translational research, or pursuing basic science investigations. Contributing to the knowledge that improves cancer outcomes is a major source of professional fulfillment.

The complexity of cancer requires critical thinking, problem-solving, and the integration of diverse information, making it a continuously engaging field for intellectually curious individuals.

The Profound Impact on Patients' Lives

Perhaps the greatest reward of being an oncologist is the opportunity to make a profound difference in the lives of patients and their families. Guiding patients through a difficult diagnosis, providing effective treatment, managing symptoms, and offering compassionate support are deeply meaningful aspects of the role.

While cures are not always possible, extending life, improving quality of life, and helping patients achieve their goals despite their illness are significant accomplishments. The long-term relationships built with patients based on trust and shared experience are often cited by oncologists as a key source of job satisfaction.

Witnessing patient resilience and contributing to positive outcomes, whether big or small, provides powerful motivation and reinforces the value of the work.

These books offer perspectives on the patient experience and the broader narrative of cancer.

Oncology Around the World: Global Opportunities

Regional Variations in Demand

The demand for oncologists varies globally, often influenced by factors like population demographics (especially aging populations), cancer incidence rates, healthcare infrastructure, and economic development. Developed countries generally face high demand due to aging populations and increased cancer detection.

In many low- and middle-income countries, there is a growing burden of cancer alongside a significant shortage of trained oncologists and necessary resources. This creates opportunities for physicians interested in global health to contribute in areas with substantial need.

Understanding regional epidemiological trends and healthcare system structures is important when considering international career options.

Working Across Borders: Settings and Requirements

Oncologists interested in working internationally may find opportunities in academic institutions, government hospitals, private clinics, or non-governmental organizations (NGOs) focused on global health initiatives.

Practicing medicine in another country typically requires navigating specific licensing and credentialing processes, which can vary significantly. Language proficiency and cultural competency are also essential for effective patient care and professional integration.

Short-term volunteer missions or collaborations through academic partnerships can provide exposure to international oncology practice without requiring full relocation or relicensing.

The Role of Telemedicine and Collaboration

Tele-oncology, the use of telecommunications technology to provide cancer care remotely, is expanding opportunities for cross-border collaboration. This can include remote consultations, virtual tumor boards (where experts discuss complex cases), and remote monitoring of patients.

While regulatory and logistical challenges exist, telemedicine holds promise for improving access to specialized oncology expertise, particularly in remote or underserved areas, both domestically and internationally.

International research collaborations also offer opportunities for oncologists to engage with colleagues worldwide, share knowledge, and participate in global clinical trials.

Frequently Asked Questions About Becoming an Oncologist

What is the typical salary range for an oncologist?

Salaries for oncologists can vary significantly based on factors like geographic location, years of experience, subspecialty, and practice setting (academic vs. private practice). Generally, oncology is a highly compensated medical specialty.

According to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), physicians and surgeons, including oncologists, are among the highest-paid occupations. Specific salary surveys from organizations like the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) often provide more detailed figures for oncology subspecialties, frequently placing median compensation well above $400,000 annually in the US, though this can change based on market conditions.

Compensation structures may include base salary, productivity bonuses, and benefits. Academic positions might offer lower direct compensation compared to private practice but may include other benefits like research support and teaching opportunities.

How competitive is it to match into an oncology fellowship?

Oncology fellowships, particularly in desirable locations or prestigious institutions, are highly competitive. Successful applicants typically have strong academic records from medical school and residency, excellent letters of recommendation, significant research experience (publications, presentations), and demonstrated interest and commitment to the field.

The competitiveness can vary slightly between subspecialties (e.g., medical oncology, radiation oncology, surgical oncology subspecialties). Prospective applicants should focus on excelling during their residency, seeking mentorship, and building a strong research portfolio.

Networking at conferences and engaging in oncology-related activities during residency can also improve an applicant's visibility and chances of matching.

Is it possible to transition into oncology after practicing in another field, like general internal medicine?

Yes, it is possible, although it typically requires completing a formal oncology fellowship program. Physicians who have completed an internal medicine residency (the standard prerequisite for medical oncology/hematology fellowships) can apply for fellowship even after spending some time in general practice or another internal medicine subspecialty.

However, the application process remains competitive. Demonstrating continued interest in oncology, perhaps through relevant continuing medical education or research activities undertaken while in practice, can strengthen an application.

For fields outside internal medicine (e.g., family medicine), transitioning would be more complex and might require additional residency training depending on the specific oncology subspecialty desired.

Is research experience essential for a clinical oncology career?

While extensive research experience is crucial for a career in academic oncology (especially for research-focused tracks), it's not strictly mandatory for purely clinical roles, particularly in community or private practice settings. However, some level of research exposure during training is generally expected and beneficial.

Understanding research methodology and being able to critically evaluate clinical trial data are important skills for all oncologists, as treatment guidelines are constantly evolving based on new evidence. Participation in clinical research, even if not leading trials, is common in many oncology practices.

Therefore, while not always essential for a purely clinical job, research experience significantly strengthens fellowship applications and provides valuable skills for evidence-based practice.

How does the choice of oncology sub-specialty impact job prospects?

Job prospects are generally strong across most oncology subspecialties due to factors like the aging population and increasing cancer incidence. However, there can be some variations based on geographic location and specific needs within healthcare systems.

Medical oncology and hematology/oncology tend to have broad applicability. Radiation oncology demand can be influenced by the distribution of radiation facilities. Surgical oncology subspecialties are tied to surgical volumes and hospital resources.

Emerging fields or those requiring highly specialized expertise might have fewer positions but also potentially less competition initially. Overall, well-trained oncologists in any major subspecialty are typically in demand.

What is the typical work-life balance for an oncologist?

Oncology is known to be a demanding field, often involving long working hours, complex patient care responsibilities, and significant emotional stress. Call schedules (being available for urgent issues after hours) are common, particularly early in one's career or in certain practice settings.

Work-life balance can vary depending on the practice setting (academic vs. private vs. community), subspecialty, and individual choices. Academic positions might involve protected time for research but also teaching and administrative duties. Private practice may offer more autonomy but potentially higher clinical volume pressures.

While challenging, achieving a reasonable work-life balance is possible, often requiring conscious effort to set boundaries, prioritize tasks, and utilize support systems. Burnout remains a significant concern in the field, highlighting the importance of addressing workload and well-being.

Useful Resources for Aspiring Oncologists

For those seriously considering a career in oncology, engaging with professional societies and exploring further resources can be invaluable. Here are a few key organizations and resources:

- American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO): A leading professional organization for physicians and oncology professionals specializing in cancer care. Offers educational resources, guidelines, and conferences.

- American Association for Cancer Research (AACR): Focuses on advancing cancer research through publications, conferences, and funding opportunities.

- National Cancer Institute (NCI): Part of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, NCI is a primary source for cancer information, research funding, and clinical trial data.

- OpenCourser Health & Medicine: Browse a wide range of online courses related to medicine, biology, and healthcare to build foundational knowledge or explore specific topics.

- OpenCourser Learner's Guide: Find tips on how to effectively use online courses for professional development and supplementing formal education.

Embarking on a career as an oncologist is a long and demanding journey requiring significant intellectual capacity, emotional resilience, and dedication. However, it offers the unique privilege of accompanying patients through one of life's most challenging experiences, contributing to a rapidly advancing scientific field, and making a tangible difference in the fight against cancer. If you possess a strong aptitude for science, excellent communication skills, deep empathy, and a desire for a challenging yet profoundly rewarding profession, oncology may be the right path for you.