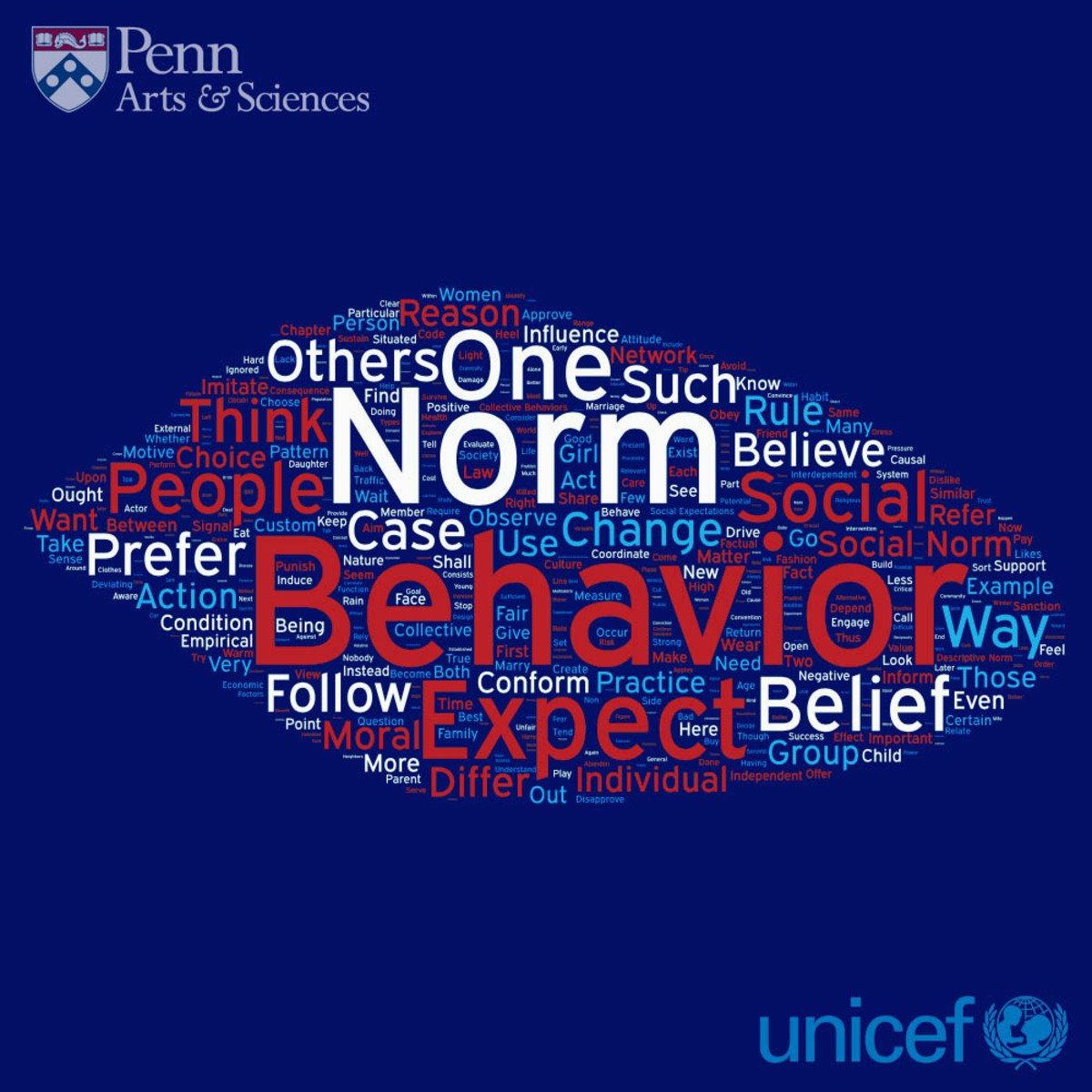

Social Norms

derstanding Social Norms: The Unseen Forces That Shape Our Lives

Social norms are the unwritten rules or shared standards of acceptable behavior within a group or society. They are the collective expectations about how people should act in various situations, guiding our decisions and interactions, often without us consciously realizing it. These norms can range from simple everyday courtesies to more complex societal expectations, and they play a crucial role in maintaining social order, predictability, and cooperation. Understanding social norms can be an engaging pursuit, as it sheds light on the intricate ways societies function and how individual behavior is profoundly shaped by the collective.

Exploring social norms can be exciting because it allows us to decipher the underlying codes of human interaction. It helps explain why people behave the way they do in different cultural contexts and how these unwritten rules contribute to the formation of identities and communities. Furthermore, understanding how norms emerge, persist, and change can empower individuals and groups to address societal challenges and foster positive social transformations.

Introduction to Social Norms

At its core, the study of social norms delves into how these shared expectations influence our daily lives, from the simplest interactions to complex societal structures. It's a field that touches upon our innate desire to belong and how that influences our actions.

What Are Social Norms? A Simple Explanation

Social norms are essentially the informal, mostly unwritten, rules that tell us what is considered acceptable and appropriate behavior within a specific group or community. Think of them as the invisible hand guiding how we interact with others. They are learned, often from a very young age, through observation, imitation, and social feedback, becoming deeply ingrained in our understanding of how to navigate social situations. These norms help create a sense of order and predictability in our interactions, making social life smoother and more cooperative.

These unwritten rules are powerful drivers of human behavior, shaping everything from our clothing choices and language to our beliefs about significant social issues. Because we are inherently social beings, we are highly sensitive to the actions and opinions of others, and this sensitivity makes us adept at recognizing and adhering to prevailing norms.

Conformity to social norms is often driven by the expectation of social acceptance or rewards, while non-conformity can lead to social punishment or exclusion. This system of social sanctions, whether formal or informal, helps to maintain and reinforce these behavioral standards within a society.

Everyday Examples of Social Norms

Social norms are all around us, guiding countless aspects of our daily routines. Consider the simple act of queuing, or waiting in line. In many cultures, it's an unspoken rule that you wait your turn, and cutting in line is met with disapproval. Greetings are another common example; whether it's a handshake, a bow, or a kiss on the cheek, the appropriate way to greet someone is dictated by social norms specific to that culture or context.

Table manners, such as not speaking with your mouth full or using utensils in a certain way, are also a set of social norms we learn. Dress codes, whether for a formal event, a place of worship, or a casual gathering, are guided by normative expectations about appropriate attire. Even the way we use public spaces, like keeping quiet in a library or offering a seat on public transport to someone in need, reflects underlying social norms. These examples illustrate how norms provide a framework for polite and orderly social interaction.

Other instances include the expectation that children attend school and that parents support their children's education. In some cultures, there are specific norms governing interactions between men and women in social gatherings, including how they dress or maintain physical distance. These everyday examples highlight the pervasive and often subtle influence of social norms on our behavior.

Why Social Norms Matter: Order, Predictability, and Cooperation

Social norms are fundamental to the functioning of any society because they provide a basis for order, predictability, and cooperation. Without norms, social interactions would be chaotic and unpredictable, as individuals would lack a shared understanding of expected behavior. Norms create a framework that allows people to anticipate how others are likely to act in various situations, reducing uncertainty and facilitating smoother interactions.

By defining what is considered acceptable, norms help to regulate behavior and prevent actions that could be disruptive or harmful to the group. This regulatory function is crucial for maintaining social cohesion and enabling collective action. When people share common expectations and adhere to them, it fosters a sense of trust and mutual understanding, which are essential for cooperation. Whether it's collaborating on a group project, participating in community activities, or engaging in economic exchange, shared norms make it possible for individuals to work together towards common goals.

Moreover, social norms contribute to the stability of a culture by creating a "stickiness" that slows down the rate of cultural change, making human behavior more predictable. This predictability reduces the inherent risks in social interaction and exchange. In essence, a society without norms is difficult to imagine, as morality and behavior would be highly unpredictable.

Descriptive vs. Injunctive Norms: What We Do vs. What We Should Do

When discussing social norms, it's useful to distinguish between two key types: descriptive norms and injunctive norms. This distinction helps to clarify the different ways in which social expectations influence our behavior. Understanding this difference is important because these two types of norms can sometimes align, but they can also conflict.

Descriptive norms refer to our perceptions of what is commonly done in a particular situation – what we believe others actually do. These norms are based on our observations of the behavior of those around us. For example, if you observe that most people in your office recycle their paper, that's a descriptive norm. The behavior is driven by the belief that it's what others in the community or social circle are doing.

Injunctive norms, on the other hand, relate to our perceptions of what behavior is approved or disapproved of by others – what we believe we should do. These norms involve a moral judgment or a sense of what is considered right or wrong within the group. For instance, the belief that littering is wrong is an injunctive norm, even if you sometimes see people littering (which would be a conflicting descriptive norm). Injunctive norms guide behavior by outlining acceptable and unacceptable actions.

Sometimes these two types of norms align perfectly: most people believe that stealing is wrong (injunctive norm), and most people do not steal (descriptive norm). However, they can also diverge. For example, many college students might believe that excessive drinking is disapproved of (injunctive norm), but they might also perceive that many of their peers engage in heavy drinking (descriptive norm). Such misperceptions between descriptive and injunctive norms can significantly influence individual choices.

These courses can help provide a foundational understanding of social norms and how they influence behavior.

Theoretical Foundations and History

The concept of social norms is not new; it has been a subject of inquiry across various academic disciplines for centuries. Understanding its intellectual history and the theoretical perspectives that have shaped its study provides a richer appreciation of this complex social phenomenon. Scholars have explored how norms function, motivate action, and influence behavior in diverse contexts.

A Journey Through Disciplines: Sociology, Psychology, Anthropology, Economics

The study of social norms is inherently interdisciplinary, with significant contributions from sociology, psychology, anthropology, and economics. Each discipline brings a unique lens to understanding how norms operate and influence human behavior.

In sociology, norms are often viewed as the rules that bind individual actions to social sanctions, thereby creating patterns that define social systems. Sociologists like Émile Durkheim and Talcott Parsons emphasized the social functions of norms in maintaining social order and how they motivate people to act in accordance with societal expectations. They explored how norms dictate interactions in all social encounters.

Psychology, particularly social psychology, focuses on how norms are perceived and processed by individuals, and how they influence individual behavior, attitudes, and identity. Research in this field examines concepts like conformity, obedience, and group influence, shedding light on the cognitive and emotional processes underlying normative behavior. The roles of norms are emphasized as mental representations of appropriate behavior.

Anthropology has a long tradition of studying social norms in different cultural contexts, describing how they function to regulate social life in diverse societies. Anthropologists like Clifford Geertz have provided rich ethnographic accounts of how norms shape rituals, customs, and social structures across cultures. This comparative perspective highlights the variability and cultural specificity of social norms.

Economics has increasingly recognized the importance of social norms in shaping economic behavior and market outcomes. Economists have explored how adherence to norms influences consumer choices, labor practices, and cooperation in economic games. Behavioral economics, in particular, integrates psychological insights about norms into economic models.

Key Theoretical Lenses

Several major theoretical perspectives offer frameworks for understanding social norms. These theories provide different explanations for why norms exist, how they function, and how they influence behavior.

Functionalism, prominent in early sociological thought, views social norms as existing to fulfill essential societal needs. From this perspective, norms arise to promote cooperation, maintain social order, and ensure the smooth functioning of social institutions. Norms are seen as solutions to problems of social coordination and collective action.

Social Learning Theory emphasizes that individuals learn norms through observation, imitation, and reinforcement. We watch others, see what behaviors are rewarded or punished, and adjust our own behavior accordingly. This perspective highlights the role of socialization and social interaction in the transmission and internalization of norms.

Game Theory, often used in economics and political science, models social interactions as strategic games. Within this framework, norms can emerge as equilibrium solutions to coordination problems or social dilemmas. Norms, often backed by sanctions, can help individuals achieve mutually beneficial outcomes that would be unattainable otherwise.

Symbolic Interactionism focuses on how norms are created, maintained, and changed through ongoing social interaction and shared meaning-making. This perspective emphasizes the interpretive processes through which individuals define situations and negotiate normative expectations. Norms are not seen as fixed rules but as dynamic and context-dependent understandings.

Social Identity Theory suggests that norms are central to group identity. Individuals categorize themselves and others into social groups, and group norms define what it means to be a member of that group. Conformity to group norms is a way of expressing and affirming one's social identity.

Influential Thinkers and Seminal Works

Numerous thinkers have made significant contributions to our understanding of social norms. In sociology, Émile Durkheim's work on social solidarity and anomie highlighted the importance of shared moral rules. Talcott Parsons developed a comprehensive theory of social action where norms are central to social systems. Erving Goffman's detailed observations of everyday interactions revealed the subtle ways in which individuals navigate and uphold social expectations, a concept he famously explored in "The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life."

In psychology, Muzafer Sherif's experiments on norm formation demonstrated how group consensus emerges in ambiguous situations. Solomon Asch's conformity experiments illustrated the powerful pressure to conform to group judgments, even when those judgments are clearly incorrect. Stanley Milgram's obedience studies showed how individuals can be compelled by authority figures to violate their own moral norms.

Anthropologists like Ruth Benedict and Margaret Mead provided cross-cultural perspectives that challenged ethnocentric assumptions about norms and behavior. In economics, thinkers like George Akerlof and H. Peyton Young have explored how norms influence market behavior and economic decision-making. Cristina Bicchieri's work has been influential in defining and analyzing social norms, distinguishing them from other social constructs.

These foundational books offer deeper insights into the theoretical underpinnings of social norms.

Evolution of Understanding Social Norms

The understanding of social norms has evolved significantly over time. Early theories often emphasized the internalization of norms through socialization, suggesting that individuals develop a deep-seated motivation to conform. Parsons, for example, argued that once a norm is internalized, conformity is driven by an internal sanctioning system. However, empirical evidence has sometimes challenged this view, showing that there isn't always a strong correlation between people's stated normative beliefs and their actual behavior, and that norms can change relatively quickly.

Later perspectives, influenced by rational choice theory and game theory, focused more on the role of external sanctions and strategic considerations in maintaining norms. These models often define norms behaviorally, based on observed patterns of behavior and the presence of punishment for deviation. However, a limitation of this approach is that not all social norms involve explicit sanctions.

More recent approaches, like social identity theory, have highlighted the connection between norms and group membership, emphasizing that individuals conform to norms because they identify with the group that upholds those norms. There is also a growing recognition of the dynamic nature of norms, with research exploring how norms emerge, spread, and change in response to social, technological, and environmental shifts. Contemporary research also increasingly employs experimental methods and computational modeling to study norm dynamics.

This course delves into the dynamics of social behavior within networks, offering insights into how norms can propagate and shift.

Types and Characteristics of Social Norms

To fully grasp the concept of social norms, it's essential to explore their various types and characteristics. Norms are not monolithic; they differ in their nature, origin, and the way they are enforced. Understanding these distinctions provides a more nuanced framework for analyzing their role in society.

Descriptive vs. Injunctive Norms Revisited

As previously introduced, the distinction between descriptive and injunctive norms is fundamental. Descriptive norms are about what people typically do – the prevalence of a behavior. They are our perceptions of how others in our social environment actually behave. For instance, observing that many people jaywalk at a particular intersection establishes a descriptive norm for jaywalking there, regardless of whether it's legally or morally sanctioned.

Injunctive norms, conversely, are about what people should do – the perceived approval or disapproval of a behavior by others. They reflect a group's moral or ethical stance on certain actions. The belief that one should not cheat on exams is an injunctive norm, stemming from the societal disapproval of academic dishonesty. These norms assist individuals in determining what is considered acceptable or unacceptable social behavior.

The interplay between these two types of norms can be complex. Sometimes they align, such as when most people believe honesty is good (injunctive) and most people are, in fact, honest (descriptive). However, conflicts can arise when what is commonly done (descriptive) diverges from what is socially approved (injunctive). For example, while there might be a strong injunctive norm against underage drinking, the descriptive norm among a particular group of teenagers might be that drinking is common. This divergence can create tension and influence individual choices significantly.

Formal vs. Informal Norms

Social norms can also be categorized based on their level of formalization and the explicitness of their rules and consequences.

Formal norms are established, written rules that are explicitly stated and often enforced by official institutions or authorities. Laws, regulations, company policies, and school rules are all examples of formal norms. These norms are typically designed to suit and serve the most people and are often accompanied by clearly defined sanctions for violations, such as fines, legal penalties, or disciplinary actions. Because they are codified, formal norms are usually the most specific and clearly stated type of norm.

Informal norms, on the other hand, are unwritten, casual behaviors that are generally and widely conformed to within a group or society. These are the unspoken rules of everyday life that we learn through observation, imitation, and general socialization. Examples include customs, traditions, etiquette, and folkways (direct, appropriate behavior in day-to-day practices). While formal norms are enforced by designated authorities, informal norms are typically enforced through social sanctions like approval, disapproval, gossip, or social exclusion. Though less codified, the list of informal norms is extensive and they govern a vast array of our personal interactions and social behaviors.

For instance, the rule against murder is a formal norm (a law), while the expectation to say "please" and "thank you" is an informal norm. Both types play crucial roles in structuring social interactions, but they operate through different mechanisms of establishment and enforcement.

To delve deeper into these distinctions, consider these influential books:

Characteristics: Strength, Scope, and Source

Beyond their type, social norms can be further understood by examining their key characteristics, such as their strength, scope, and source.

Norm strength refers to how clear a norm is and how consistently it is enforced. Strong norms are widely understood, broadly accepted, and violations are met with significant social sanctions (either positive for adherence or negative for deviation). For example, the norm against physical violence in most public settings is typically a strong norm. Weak norms, conversely, may be ambiguous, less widely accepted, or inconsistently enforced. The degree of deviance tolerated often depends on the perceived importance of the norm; well-entrenched social norms usually see almost universal compliance.

Norm scope relates to the range of situations or groups to which a norm applies. Some norms are highly situational, applying only in specific contexts (e.g., norms for behavior in a place of worship versus a sports stadium). Other norms are group-specific, applying only to members of a particular community, profession, or social group (e.g., the dress code for a specific company). Some norms might be very broad, applying across many situations and to a large population, while others are narrow and context-dependent.

Norm source refers to the origin or basis of a norm's authority. Norms can derive their legitimacy from various sources. Some norms are established by formal authorities, such as governments enacting laws or organizations setting policies (formal norms). Other norms emerge from social consensus and shared practices within a group (informal norms). The perceived legitimacy of the source can significantly impact adherence to the norm. For example, a norm is more likely to be followed if it is seen as fair, just, and originating from a respected authority or a shared community understanding.

Understanding these characteristics helps in analyzing why some norms are more influential than others and how they operate in different social settings. For example, a strong, broadly scoped norm with a legitimate source is likely to have a powerful impact on behavior.

Illustrative Examples

Let's consider some examples to illustrate these types and characteristics.

A formal, strong, and broadly scoped norm is the law against theft. It's written (formal), violations are consistently punished by the legal system (strong), and it applies to almost everyone in society across most situations (broad scope). Its source is governmental authority.

An example of an informal, relatively strong, and group-specific norm could be the expectation within a particular group of friends to always split the bill equally at a restaurant. It's unwritten (informal), there might be social awkwardness or disapproval if someone consistently deviates (relatively strong within that group), and it applies specifically to that circle of friends (group-specific). Its source is the consensus and shared practice of that group.

A descriptive norm could be observing that most people in your neighborhood put out their recycling bins on a specific day. An injunctive norm related to this might be the shared belief that recycling is good for the environment and that people should recycle. If both norms align (most people recycle and believe it's the right thing to do), the behavior is strongly reinforced.

Consider the norm of punctuality. In some cultures or professional settings, this is a very strong norm (high clarity and enforcement through disapproval or even penalties for lateness). Its scope might be specific to work or formal appointments. Its source is often a shared understanding of respect for others' time and efficiency. In other contexts, punctuality might be a weaker or less strictly enforced norm.

These examples demonstrate how classifying norms by type and analyzing their characteristics provides a clearer understanding of their influence on social behavior.

Norm Formation, Maintenance, and Change

Social norms are not static; they emerge, persist, and evolve over time. Understanding the processes behind norm formation, maintenance, and change is crucial for comprehending social dynamics and for efforts aimed at fostering positive societal shifts. Research in this area explores how unwritten rules come into being, why they stick around, and what factors can lead to their transformation.

How Do Social Norms Emerge?

The emergence of social norms is a complex process that can be driven by various factors. Several theories offer explanations for how these unwritten rules come to be established within a group or society.

One perspective is that norms arise to solve coordination problems. When individuals need to coordinate their actions to achieve a common goal or avoid conflict, shared expectations about behavior can emerge naturally. For example, norms about which side of the road to drive on help prevent accidents and facilitate traffic flow.

Norms can also emerge as a way of signaling information about oneself or one's group. Adhering to certain norms can signal membership, commitment, or status. For instance, adopting specific fashion trends or linguistic styles can signal affiliation with a particular subculture.

Cultural evolution theories suggest that norms can develop and spread through processes analogous to biological evolution, such as variation, selection, and transmission. Behaviors that are beneficial to individuals or groups may become normative over time as they are adopted and passed on. The social comparison theory, for example, posits that interpersonal interactions and agreement among group members are fundamental to norm formation.

Sometimes, norms emerge from the actions of norm entrepreneurs – individuals or groups who actively work to promote new standards of behavior. These entrepreneurs may advocate for a new norm because they believe it is morally right or beneficial to society. Their efforts, if successful, can lead to the establishment of a new shared expectation.

Furthermore, some scholars argue that norms arise when an individual's behavior has consequences (externalities) for other members of the group. If an activity produces negative effects on others, a norm may emerge to regulate that activity, often introducing a system of sanctions or rewards.

Mechanisms of Norm Enforcement

Once norms are established, various mechanisms work to ensure compliance and maintain their stability. These enforcement mechanisms can be both formal and informal, and they play a critical role in discouraging deviations and reinforcing normative behavior.

Social sanctions are a primary mechanism of norm enforcement. These can be positive (rewards for conformity) or negative (punishments for non-conformity). Positive sanctions might include praise, acceptance, or increased status, while negative sanctions can range from disapproval, ridicule, and gossip to more severe forms like ostracism, fines, or legal penalties. The effectiveness of a norm is often tied to its ability to enforce these sanctions.

Internalization is another powerful mechanism. Through socialization, individuals may come to internalize norms, meaning they adopt the normative beliefs and values as their own. When a norm is internalized, conformity is driven by an internal sense of obligation or a belief that the behavior is inherently right, rather than solely by the fear of external sanctions.

Reputation plays a significant role in norm enforcement, especially in communities where individuals interact repeatedly or where information about behavior circulates. The desire to maintain a good reputation can motivate individuals to adhere to norms, as a damaged reputation can lead to social exclusion or loss of opportunities.

Groups often control resources, and they can use these to reward adherence to norms or punish non-adherence, effectively controlling member behavior. This is particularly true when individuals value these resources or see group membership as central to their identity.

Factors Influencing Norm Persistence and Stability

Several factors contribute to the persistence and stability of social norms over time. One key factor is the continued effectiveness of enforcement mechanisms. As long as sanctions are applied consistently and conformity is rewarded, norms are likely to remain stable.

The degree of internalization also plays a crucial role. Norms that are deeply internalized by a majority of group members are more resistant to change because individuals are self-regulating their behavior based on shared values. The utility of the norm is also a significant determinant; norms that are perceived to lead to the betterment of social life and fulfill group needs are more likely to be valued, reinforced, and followed.

The interconnectedness of norms within a broader cultural system can also contribute to their stability. Norms are often linked to other beliefs, values, and practices, forming a coherent cultural framework. Changing one norm may require adjustments in other parts of this framework, making widespread change more difficult.

Furthermore, the perceived legitimacy of a norm and its source influences its stability. If individuals believe a norm is fair, just, and originates from a credible source (e.g., tradition, respected authority, democratic consensus), they are more likely to uphold it. Conversely, if the enforcers of norms are perceived as biased or self-serving, they might lose their authority, potentially destabilizing the norm.

Processes of Norm Change

Despite their tendency towards stability, social norms are not immutable and can change over time. The process of norm change can be driven by various factors and can occur gradually or relatively rapidly.

Norm entrepreneurs and social movements often play a crucial role in initiating norm change. By challenging existing norms and advocating for new ones, these actors can raise awareness, shift public opinion, and mobilize collective action. If they successfully persuade others of the desirability and appropriateness of new behaviors, a norm cascade can occur, leading to broad acceptance and eventually internalization of the new norm.

Technological shifts can also drive norm change. For example, the rise of the internet and social media has profoundly altered norms related to communication, privacy, and social interaction.

Legal interventions and policy changes can be powerful catalysts for norm change. Laws that prohibit certain behaviors (e.g., smoking in public places, discrimination) can gradually shift societal expectations and behaviors, especially when accompanied by effective enforcement and public education campaigns.

Changing environmental or social conditions can also lead to the evolution of norms. For instance, increased awareness of environmental issues has led to the emergence of new norms around recycling and sustainability. Similarly, major events like pandemics can rapidly alter norms related to hygiene and social distancing.

The process of norm change often involves a period of contestation and negotiation, as new an M. Gelfand explores how "tight" and "loose" cultures differ in their adherence to social norms.

The following courses delve into the dynamics of social change and the mechanisms through which norms evolve. These may be particularly interesting for those looking to understand or influence societal shifts.

The Impact of Social Norms Across Domains

Social norms are not confined to a specific sphere of life; their influence is pervasive, shaping behavior and outcomes across a multitude of domains. From individual decision-making to the functioning of complex social systems, norms act as a fundamental organizing principle. Understanding this broad impact highlights the significance of social norms in virtually every aspect of human existence.

Influence on Individual Behavior: Conformity, Decision-Making, Identity

At the individual level, social norms exert a powerful influence on our behavior, choices, and even our sense of self. The pressure to conform to group expectations is a well-documented psychological phenomenon. Individuals often adjust their behavior to align with perceived norms to gain social approval, avoid disapproval, or maintain a sense of belonging. This can affect a wide range of actions, from fashion choices and consumer preferences to more significant life decisions.

Social norms also play a crucial role in decision-making. When faced with uncertainty or ambiguity, individuals often look to the behavior and opinions of others as a guide for how to act (informational social influence). Perceived norms can shape our risk assessments, our moral judgments, and the options we consider viable. For example, if a particular health behavior is perceived as normative within one's peer group, an individual is more likely to adopt that behavior.

Furthermore, social norms contribute significantly to the formation and maintenance of identity. The groups we belong to (e.g., family, cultural group, professional community) are often defined by shared norms and values. By adhering to these norms, individuals affirm their membership and express their social identity. Conversely, violating group norms can threaten one's sense of belonging and identity.

Role in Group Dynamics: Cohesion, Conflict, Productivity

Within groups, social norms are essential for regulating interactions and shaping collective outcomes. Norms contribute to group cohesion by providing a shared framework of expectations and behaviors. When members understand and adhere to common rules, it fosters a sense of unity, trust, and predictability, making the group more effective and harmonious.

However, norms can also be a source of conflict within and between groups. When individuals or subgroups hold differing normative expectations, or when existing norms are challenged, tensions can arise. Conflict can also occur when the norms of one group clash with those of another, leading to misunderstandings or intergroup friction.

Social norms significantly impact group productivity and performance. Clear and supportive norms regarding collaboration, communication, and effort can enhance a group's ability to achieve its goals. Conversely, dysfunctional norms, such as those tolerating shirking or promoting unhealthy competition, can undermine group effectiveness. In organizational settings, for example, norms around work ethic, punctuality, and quality of work directly influence overall output and success.

These books offer valuable perspectives on how social dynamics and individual psychology are shaped by normative influences.

Shaping Culture, Traditions, and Social Institutions

Social norms are the bedrock of culture and traditions. Culture, in many ways, can be understood as a complex system of shared norms, values, beliefs, and practices that are transmitted across generations. Norms define what is considered polite, respectful, beautiful, or sacred within a particular cultural context. They shape rituals, ceremonies, social etiquette, and artistic expressions. Traditions are essentially long-standing norms that have been passed down and are often imbued with historical and symbolic significance.

Norms are also fundamental to the structure and functioning of social institutions. Institutions like the family, education, government, and the economy are all built upon and regulated by sets of formal and informal norms. For example, norms about marriage and kinship define family structures; norms about teaching and learning shape educational systems; and norms about fairness and reciprocity underpin economic exchange. The stability and legitimacy of these institutions depend, in large part, on the widespread acceptance and adherence to their underlying norms.

Impact on Economic Behavior and Political Systems

The influence of social norms extends deeply into the realms of economic and political life. In the economic sphere, norms affect a wide range of behaviors, including consumer choices, saving and investment patterns, work ethic, and business practices. For instance, norms around conspicuous consumption can drive purchasing decisions, while norms of reciprocity and trust can facilitate trade and investment. Ethical norms can influence corporate social responsibility and fair labor practices. The World Bank has noted how gendered social norms can impact economic growth by, for example, limiting women's participation in the workforce.

In political systems, social norms shape citizen behavior, political participation, and the functioning of governance. Norms regarding civic duty can influence voting turnout and engagement in community affairs. Norms of political discourse affect the tone and civility of public debate. The acceptance and legitimacy of political institutions and leaders are also heavily influenced by whether their actions align with prevailing social and ethical norms. Furthermore, norms can play a role in policy acceptance; policies that are perceived as conflicting with deeply held social norms may face resistance, regardless of their technical merits.

Understanding the interplay between social norms and these broader systems is crucial for policymakers and leaders seeking to foster economic development, social progress, and effective governance.

This course explores the psychological aspects of diversity and how unconscious biases, often rooted in social norms, can affect interactions and decisions.

Social Norms in Practice: Applications

The theoretical understanding of social norms has significant practical applications across various fields. By recognizing how norms shape behavior, practitioners can design more effective interventions and strategies to achieve specific goals, whether in public health, marketing, policy, or organizational management. Leveraging social norms can lead to tangible outcomes and positive social change.

Marketing and Consumer Behavior

In the field of marketing, understanding social norms is crucial for influencing purchasing decisions and shaping brand perception. Marketers often tap into descriptive norms by highlighting the popularity of a product ("everyone's buying it") or injunctive norms by associating their brand with socially approved values or lifestyles (e.g., sustainability, health consciousness).

Advertising campaigns frequently use "social proof" by showing satisfied customers or emphasizing that a product is a bestseller. This leverages the human tendency to conform to what others are doing. Similarly, brands may try to create new norms around their products, positioning them as essential or desirable within a particular social group. For instance, technology companies often succeed by making their latest gadgets the "norm" for communication or entertainment.

Understanding the reference groups that influence a target audience is also key. If a product can be positioned as normative within an aspirational group, it can significantly increase its appeal. However, misjudging or misrepresenting norms can backfire, leading to campaigns that are ineffective or even alienate consumers.

These books provide insights into the psychology of persuasion and decision-making, highly relevant to marketing and consumer behavior.

Public Health Campaigns

Social norms approaches are widely used in public health to promote healthy behaviors and discourage harmful ones. Campaigns often aim to correct misperceptions about norms. For example, many college students overestimate the prevalence and acceptability of binge drinking among their peers. Social norms marketing campaigns can present accurate data showing that most students drink moderately or not at all, thereby shifting the perceived descriptive norm and reducing pressure to overconsume.

This approach has been applied to various health issues, including smoking cessation, vaccination uptake, hygiene practices (like handwashing), and sexual health. Instead of simply telling people what to do, these campaigns provide accurate information about what others are doing (descriptive norms) and what is generally approved of (injunctive norms), empowering individuals to make healthier choices. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is one organization that utilizes the social norms approach to motivate positive health behaviors.

The success of these campaigns often depends on carefully researching the existing norms and misperceptions within the target population and tailoring messages accordingly. For example, the World Health Organization discusses how social norms impact women's health, including practices like female genital mutilation and child marriage, and the importance of addressing these norms.

This course directly addresses the use of social norms for social change, which is highly relevant to public health initiatives.

Policy Design and Implementation

Understanding social norms is critical for effective policy design and implementation. Policies that align with existing social norms are more likely to be accepted and adhered to by the public. Conversely, policies that clash with deeply entrenched norms may face resistance, non-compliance, or unintended negative consequences, even if they are well-intentioned and technically sound.

For example, in environmental protection, policies aimed at encouraging recycling or reducing energy consumption are more effective when they leverage social norms. Programs that provide feedback to households on how their energy use compares to their neighbors (a descriptive norm intervention) have been shown to reduce consumption. In tax compliance, appealing to the injunctive norm that paying taxes is a civic duty, and the descriptive norm that most people comply, can improve adherence.

Policymakers can also work to shift harmful norms through legal changes and public awareness campaigns. For instance, laws against discrimination, coupled with efforts to promote inclusivity, can gradually change societal norms regarding the treatment of minority groups. The World Bank emphasizes that policy interventions should be "norms-aware" and use tools to support more equal gender norms where appropriate. This involves not just changing attitudes but also addressing the contexts that support norm adherence.

Organizational Behavior and Human Resources

Within organizations, social norms significantly shape company culture, team collaboration, employee behavior, and overall performance. Human Resources (HR) professionals and managers can leverage an understanding of norms to foster positive and productive work environments.

Norms related to communication, punctuality, meeting etiquette, dress code, and effort levels all contribute to the unwritten rules of an organization. Strong, positive norms can enhance teamwork, encourage ethical behavior, and improve employee morale and productivity. For example, a norm of open communication and mutual respect can foster a more collaborative and innovative culture.

HR can play a role in establishing and reinforcing desired norms through onboarding processes, training programs, leadership modeling, and performance management systems. Addressing dysfunctional norms, such as those that tolerate bullying or discourage speaking up, is also crucial for creating a healthy workplace. Initiatives related to diversity and inclusion often involve challenging existing exclusionary norms and promoting new norms of equity and belonging.

Researching Social Norms: Methods and Challenges

Studying social norms is a complex endeavor, requiring researchers to navigate the intricacies of human behavior, beliefs, and social interactions. A variety of methodologies are employed to identify, measure, and understand norms, but researchers also face significant challenges in capturing these often unstated and context-dependent rules.

Common Methodologies

Researchers from various disciplines use a range of qualitative and quantitative methods to investigate social norms.

Surveys and Questionnaires: These are widely used to measure individuals' perceptions of what others do (descriptive norms) and what others approve of (injunctive norms). Questions might ask about perceived peer behavior or attitudes regarding a specific action. Self-report data, however, can be subject to biases.

Vignette Studies: Participants are presented with hypothetical scenarios (vignettes) and asked to judge the appropriateness of different behaviors or to predict how others would react. This method can help elicit normative judgments in a controlled way.

Experiments (Lab and Field): Experimental methods allow researchers to manipulate variables and observe their effects on normative behavior. Lab experiments offer high control but may lack ecological validity. Field experiments, conducted in real-world settings, can provide more generalizable insights into how norms operate naturally. For example, researchers might subtly alter perceived norms in a community and observe changes in behavior related to energy conservation or charitable giving.

Ethnographic Observation: Anthropologists and sociologists often use ethnographic methods, including participant observation and in-depth interviews, to gain a rich, contextualized understanding of norms within a specific cultural group or community. This approach allows for the discovery of subtle, unstated norms that might be missed by other methods.

Network Analysis: This method examines the structure of social relationships within a group to understand how norms spread and are maintained. It can identify influential individuals or subgroups in norm transmission and enforcement.

Computational Social Science: With the rise of big data from online platforms and digital interactions, researchers are increasingly using computational methods to analyze large datasets for patterns of normative behavior and language. This can provide insights into norm dynamics at a large scale.

Challenges in Measurement

Measuring social norms accurately presents several challenges for researchers.

One major difficulty is distinguishing personal beliefs from perceived social norms. An individual's own attitude towards a behavior might differ from what they believe others think or do. Survey questions must be carefully designed to capture these distinct constructs.

Social desirability bias is another common issue. When asked about sensitive behaviors or beliefs, individuals may respond in a way they perceive as socially acceptable rather than truthfully reporting their own views or actions. This can distort measures of both personal attitudes and perceived norms.

Norms are often context-dependent and implicit. What is considered normative can vary significantly across different situations, cultures, and social groups. Many norms are unstated and operate below the level of conscious awareness, making them difficult to articulate or measure directly.

Identifying the relevant reference group is also crucial and challenging. Whose opinions and behaviors actually matter to an individual when they are forming their perceptions of norms? The reference group can vary depending on the behavior and the individual.

Furthermore, it can be difficult to capture the dynamic nature of norms. Norms are not static; they evolve, and measurement at a single point in time may not reflect ongoing processes of norm change or contestation.

Ethical Considerations in Norms Research

Research on social norms also raises specific ethical considerations that researchers must address.

When interventions involve manipulating social information to change perceived norms (e.g., in social norms marketing campaigns), there are ethical questions about the potential for deception, even if the goal is to promote positive behavior. Transparency and informed consent are important considerations.

There is a risk of unintentionally reinforcing harmful norms. If research highlights the prevalence of a negative behavior (even if to correct misperceptions about its approval), it could inadvertently normalize that behavior for some individuals.

Researchers must be sensitive to cultural differences and avoid imposing their own normative judgments on the groups they study. What is considered a "positive" or "negative" norm can be culturally relative, and interventions must be culturally appropriate and respectful.

Protecting the privacy and confidentiality of participants is paramount, especially when studying sensitive behaviors or beliefs that could lead to social stigma if revealed.

The potential for dual use of norms research also needs consideration. Understanding how to influence norms can be used for pro-social ends but could also be exploited for manipulative purposes.

This book delves into advanced topics relevant to experimental research in social psychology, which often involves the study of norms.

Interdisciplinary Approaches and Data Sources

Given the multifaceted nature of social norms, interdisciplinary approaches are increasingly common and valuable in norms research. Combining insights and methods from sociology, psychology, anthropology, economics, and other fields can lead to a more comprehensive understanding.

The availability of large-scale digital datasets (e.g., from social media, online forums, e-commerce) has opened up new avenues for studying norms. Computational social science techniques, such as natural language processing and network analysis, can be applied to these datasets to identify emerging norms, track their spread, and analyze normative language.

Integrating qualitative and quantitative methods (mixed-methods research) can also provide richer insights. Ethnographic observations can help identify context-specific norms and generate hypotheses, while surveys and experiments can test these hypotheses more systematically and on larger samples.

Cross-cultural comparative research is essential for understanding the universality versus cultural specificity of different norms and norm-related processes. This often requires collaboration between researchers from different cultural backgrounds.

Furthermore, there's growing interest in using insights from behavioral science and nudge theory to design interventions that subtly shift normative environments to encourage desirable behaviors, often through collaborations between academics and practitioners in policy or public health.

Formal Education Pathways

For individuals interested in a deep and systematic study of social norms, several formal education pathways offer relevant knowledge and research opportunities. Understanding social norms is often integrated into broader disciplines that examine human behavior, society, and culture. Pursuing these fields can provide the theoretical grounding and analytical skills necessary to research or apply knowledge about social norms in various professional contexts.

Relevant Fields of Study at University

Several academic disciplines at the university level provide a strong foundation for understanding social norms. These fields often intersect, offering a multi-faceted perspective on the topic.

Sociology is a core discipline for studying social norms, examining how they are formed, maintained, enforced, and how they contribute to social order and social change. Courses in sociological theory, social psychology, sociology of culture, and specific subfields like criminology or sociology of the family will cover norms extensively.

Psychology, particularly social psychology, delves into the individual-level processes related to norms, such as conformity, obedience, group influence, and the cognitive and affective underpinnings of normative behavior. Developmental psychology also explores how children learn and internalize social norms.

Anthropology provides a cross-cultural perspective on social norms, with ethnography as a key method for understanding how norms operate in diverse societies and shape cultural practices, rituals, and social structures. Cultural anthropology and linguistic anthropology are particularly relevant.

Economics, especially behavioral economics, incorporates the study of social norms to understand how they influence economic decision-making, market behavior, cooperation, and the effectiveness of incentives. Game theory, often taught in economics departments, is also relevant for modeling norm emergence and enforcement.

Political Science examines norms in the context of political behavior, institutions, international relations, and public policy. Scholars in this field study how norms shape voting patterns, political ideologies, diplomatic practices, and the legitimacy of governance.

Behavioral Science is an emerging interdisciplinary field that draws heavily from psychology and economics to understand and influence behavior, with a significant focus on the role of social norms and cognitive biases in decision-making.

Students can explore these fields through Social Sciences or specific disciplines like Psychology and Anthropology on OpenCourser.

Typical Coursework and Concepts

Within these fields, typical coursework related to social norms would cover a range of concepts. Students will likely encounter theories of social influence, conformity, and obedience. They will learn about group dynamics, social identity, and intergroup relations.

Courses will often discuss research methods used to study norms, including experimental design, survey research, ethnographic methods, and statistical analysis. Key concepts such as socialization (the process of learning norms), deviance (violation of norms), and social control (mechanisms for enforcing norms) are central.

Students will explore different types of norms (descriptive, injunctive, formal, informal) and their characteristics. The curriculum may also cover the functions of norms in maintaining social order, facilitating cooperation, and their role in social change. Specific applications, such as norms in health behavior, organizational culture, or consumer choices, might also be addressed.

This book provides a broad overview of social theory, which is foundational to understanding sociological approaches to norms.

Graduate Studies and Specialization

For those seeking to specialize in the study of social norms or conduct advanced research, graduate studies (Master's or PhD) offer opportunities for in-depth exploration. At the graduate level, students can focus their research on specific aspects of social norms, such as their formation, their impact on particular behaviors (e.g., health, environmental, economic), or the mechanisms of norm change.

Graduate programs in sociology, social psychology, behavioral economics, and cultural anthropology often have faculty members whose research centers on social norms. Students can work closely with these experts on research projects, develop advanced methodological skills, and contribute to the theoretical understanding of norms.

Specialization might involve focusing on a particular theoretical approach (e.g., evolutionary game theory, social identity theory) or a specific empirical domain (e.g., norms in online communities, organizational norms, norms related to gender or ethnicity). A PhD is typically required for academic research positions and some high-level policy or consulting roles that require deep expertise in social norms.

Interdisciplinary Programs and Centers

Many universities host interdisciplinary programs or research centers that focus on behavior, culture, decision-making, or social change, where the study of social norms is a central theme. These centers often bring together faculty and students from diverse departments like psychology, sociology, economics, political science, public health, and communications.

Examples include centers for behavioral decision research, institutes for social and policy research, centers for the study of culture and society, or programs in behavioral science and public policy. Participating in such interdisciplinary environments can provide a broader perspective on social norms and foster collaborations that bridge traditional disciplinary boundaries.

These programs may offer specialized seminars, workshops, and research opportunities focused on applying insights about social norms to real-world problems, such as promoting sustainable behaviors, improving public health outcomes, or reducing social inequalities. Prospective students interested in social norms should investigate such interdisciplinary offerings at universities they are considering.

These courses offer foundational knowledge relevant to understanding the individual and societal aspects of norms, which are often explored in interdisciplinary settings.

Online Learning and Self-Study Resources

Beyond formal university programs, a wealth of online learning resources and self-study materials are available for those interested in understanding social norms. Online courses, academic journals, books, and publicly available research can provide valuable knowledge, whether you're a curious learner, a student seeking supplementary material, or a professional looking to pivot or enhance your career by understanding these powerful social influences.

Availability and Types of Online Courses

Online learning platforms offer a growing number of courses relevant to the study of social norms. While dedicated courses titled "Social Norms" might be less common than broader subjects, relevant content is often embedded within courses on:

Social Psychology: These courses frequently cover topics like conformity, group behavior, social influence, and attitudes, all of which are central to understanding norms.

Sociology: Introductory sociology courses, as well as more specialized ones on topics like culture, deviance, or social problems, will discuss the role of norms in society.

Behavioral Economics: Courses in this area often explore how social norms, alongside cognitive biases, affect decision-making in economic and social contexts. Concepts like "nudging" and social proof are relevant here.

Cultural Studies or Anthropology: These courses may offer insights into how norms vary across cultures and shape social practices.

Public Health: Some public health courses, particularly those focused on health behavior change or health promotion, will discuss social norms marketing and other norm-based interventions.

When searching for courses on platforms like OpenCourser, using keywords such as "social psychology," "behavioral science," "sociology of culture," or "social influence" can yield relevant results. OpenCourser allows learners to easily browse through thousands of courses, save interesting options to a list, compare syllabi, and read summarized reviews to find the perfect online course.

These selected online courses provide direct insights into social norms, social change, and related psychological phenomena, making them excellent starting points for self-study.

Feasibility for Foundational Understanding or Supplementing Education

Online courses are highly suitable for building a foundational understanding of social norms. They can introduce key concepts, theories, and research findings in an accessible format. For students already enrolled in formal academic programs, online resources can serve as excellent supplementary material, offering different perspectives or deeper dives into specific topics covered in their university coursework.

Professionals can use online courses to gain knowledge about social norms relevant to their field, such as marketers learning about consumer psychology or public health workers exploring norm-based interventions. The flexibility of online learning allows individuals to study at their own pace and fit learning around their existing commitments.

While online courses provide a strong starting point, achieving deep expertise or research capabilities typically requires more intensive study, often within a formal academic setting, especially at the graduate level. However, for gaining a solid grasp of the fundamentals or for targeted learning, online platforms are an invaluable resource. OpenCourser's Learner's Guide offers articles on topics such as creating a structured curriculum for yourself and how to remain disciplined when self-learning.

Applying Knowledge Through Self-Directed Projects

Learners can enhance their understanding of social norms by applying their knowledge through self-directed observation or small projects. This hands-on approach can make the concepts more tangible and reveal the subtle ways norms operate in everyday life.

One could, for example, choose a specific social setting (e.g., a coffee shop, a public park, an online forum) and systematically observe behaviors. Try to identify recurring patterns: What seems to be the "unwritten rule" for how people interact, dress, or use the space? Note instances of conformity and any reactions to behaviors that seem to deviate from the norm.

Another project could involve analyzing norms in online communities. Different forums or social media groups often develop their own distinct norms for communication, topic relevance, and acceptable behavior. Observing these digital interactions can be very insightful. One might even try a small, ethical "breaching experiment" (with caution and respect for others), where a very minor, harmless norm is subtly violated to observe reactions – for example, facing the "wrong" way in an elevator for a few seconds.

Comparing norms across different cultural contexts, even through media or conversations with people from different backgrounds, can also be illuminating. These activities help solidify understanding and develop a keener eye for the social architecture that norms provide.

Critical Evaluation and Limitations

While online resources and self-study are valuable, it's important to approach them with a degree of critical evaluation. Not all online content is created equal. Learners should prioritize materials from reputable institutions, established academics, or well-regarded organizations. Checking reviews, instructor credentials, and the sponsoring institution can help assess the quality of online courses.

It's also important to recognize the limitations of self-study compared to formal academic programs, particularly for those aiming for deep expertise or careers in research. Formal programs offer structured curricula, direct interaction with experts, mentorship, and opportunities for rigorous research training that are difficult to replicate entirely through self-study. Online learning is excellent for foundational knowledge and specific skill acquisition but may not provide the same depth of critical analysis or nuanced understanding as a dedicated degree program.

Furthermore, the field of social norms is dynamic, with ongoing research and evolving theories. Staying updated with current academic literature, often found in peer-reviewed journals, is important for a contemporary understanding, and access to these journals may sometimes be easier through university affiliations. However, many researchers also share their work through pre-prints or university repositories, making some cutting-edge research accessible.

These books are considered foundational or highly insightful in the study of social behavior and norms, offering robust material for self-study.

Challenges, Criticisms, and Negative Aspects

While social norms are essential for social order and cooperation, they are not inherently benign. They can also perpetuate harmful practices, stifle creativity, and create ethical dilemmas. A balanced understanding requires acknowledging these negative aspects and the complexities associated with challenging or evaluating norms.

Harmful or Dysfunctional Norms

Many societies grapple with social norms that are harmful or dysfunctional, leading to negative consequences for individuals or entire groups. Examples are numerous and can be found across various domains.

Discrimination and Prejudice: Norms can underpin discriminatory attitudes and behaviors towards certain groups based on race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, or other characteristics. For example, norms that devalue women's capabilities can limit their educational and economic opportunities. Oxfam International highlights how harmful social norms contribute to gender inequality and violence against women and girls, such as expectations of female submissiveness or male control.

Harmful Traditions: Some cultural traditions, while deeply entrenched, can be detrimental to health or well-being. Practices like female genital mutilation, child marriage, or certain dietary restrictions based on outdated beliefs are examples of harmful traditional norms. These norms are often maintained by strong social pressure and fear of ostracism.

Corruption and Unethical Behavior: In some contexts, norms of corruption can become widespread, making bribery or illicit dealings seem like standard practice. Similarly, norms within certain organizational cultures might tolerate or even encourage unethical business practices.

Risky Health Behaviors: Social norms can also promote unhealthy lifestyles. For example, norms around heavy alcohol consumption in certain social circles, smoking as a sign of sophistication in past eras, or the glorification of extreme thinness can lead to significant health problems.

Recognizing and addressing these harmful norms is a significant challenge for social reformers and policymakers.

This book provides a specific example of how a harmful behavior can become normalized within a society.

Downsides of Conformity Pressure

While conformity is often necessary for social cohesion, excessive conformity pressure can have significant downsides.

Stifling Innovation and Creativity: When there is strong pressure to adhere to existing norms, individuals may be hesitant to express novel ideas or experiment with new approaches. This can stifle innovation, creativity, and critical thinking, as people may fear being seen as deviant or disruptive. Progress often relies on individuals who are willing to challenge the status quo.

Pluralistic Ignorance: This occurs when a majority of group members privately reject a norm but incorrectly assume that most others accept it, and therefore go along with it. For example, students in a classroom might be confused by a lecture but refrain from asking questions because they assume everyone else understands. This collective misjudgment can perpetuate unpopular or inefficient norms.

Groupthink: In highly cohesive groups, the pressure to conform can lead to groupthink, where members prioritize consensus and agreement over critical evaluation of alternatives. This can result in poor decision-making, as dissenting opinions are suppressed or self-censored.

Loss of Individuality: Constant pressure to conform can lead to a loss of individuality and personal autonomy, as individuals may feel compelled to suppress their true thoughts, feelings, or preferences to fit in with the group.

A healthy society often requires a balance between adherence to beneficial norms and the freedom for individuals to express dissent and challenge existing ways of thinking.

Resistance to Changing Entrenched Norms

Changing deeply entrenched social norms, even those that are widely recognized as harmful or outdated, can be incredibly difficult. Several factors contribute to this resistance.

Vested Interests: Some individuals or groups may benefit from existing norms and resist changes that threaten their power, status, or advantages. For example, those in positions of authority under a discriminatory system may oppose efforts to promote equality.

Fear of Social Sanctions: The fear of disapproval, ridicule, or ostracism from one's community can be a powerful deterrent to challenging established norms. Even if individuals privately disagree with a norm, they may conform publicly to avoid negative social consequences.

Internalization: When norms are deeply internalized, they become part of an individual's worldview and identity. Challenging such norms can feel like questioning one's own fundamental beliefs, leading to psychological resistance.

Lack of Viable Alternatives: Sometimes, people adhere to existing norms simply because they are unaware of or do not see viable alternatives. For change to occur, new, more beneficial norms often need to be clearly articulated and demonstrated as practical.

Interconnectedness of Norms: As mentioned earlier, norms are often part of a larger cultural system. Changing one norm may have ripple effects on other related beliefs and practices, making the overall process of change complex and slow. Social change often requires sustained effort from multiple actors and can take generations.

Ethical Dilemmas: Cultural Relativism vs. Universal Human Rights

The evaluation of social norms, particularly across different cultures, often gives rise to complex ethical dilemmas, most notably the tension between cultural relativism and the concept of universal human rights.

Cultural relativism is the idea that a person's beliefs, values, and practices should be understood based on that person's own culture, rather than be judged against the criteria of another. From this perspective, there are no universal moral standards, and what is considered "right" or "wrong" is culturally determined. This view encourages tolerance and respect for cultural diversity but can become problematic when it comes to norms that cause significant harm or violate basic human dignity.

On the other hand, the concept of universal human rights posits that all individuals, regardless of their cultural background, are entitled to certain fundamental rights and freedoms. From this standpoint, some norms, even if culturally accepted, may be deemed unacceptable if they infringe upon these universal rights (e.g., norms that condone torture, slavery, or severe forms of discrimination).

Navigating this tension is a significant challenge in international development, human rights advocacy, and cross-cultural interactions. While it is important to approach different cultures with sensitivity and avoid ethnocentrism, there is also a moral imperative to address practices that cause profound suffering or injustice. Finding ways to promote positive social change that respects cultural contexts while upholding universal human rights requires careful dialogue, engagement with local communities, and a nuanced understanding of the specific norms in question.

This course delves into the protection of vulnerable populations, a topic where the clash between local norms and universal rights often becomes apparent.

These books offer critical perspectives on morality, societal rules, and justice, relevant to discussing the challenging aspects of social norms.

Careers Leveraging Understanding of Social Norms

While "Social Norms Expert" isn't typically a standalone job title, a deep understanding of how social norms function and influence behavior is an incredibly valuable asset in a wide array of professions. Many careers involve understanding, predicting, or influencing human behavior, and in these roles, knowledge of social norms can significantly contribute to success. For those considering a career path or a pivot, developing this understanding can open doors to diverse and impactful opportunities.

Identifying Relevant Career Fields

An understanding of social norms is highly beneficial in numerous fields. Some key areas include:

Marketing and Advertising: Professionals in this field constantly work with and try to shape consumer perceptions and behaviors, which are heavily influenced by social norms. Understanding what is considered trendy, aspirational, or socially acceptable is crucial for creating effective campaigns.

User Experience (UX) Research and Design: UX professionals aim to create products and services that are intuitive and meet user needs. Understanding users' existing norms and expectations for how digital interfaces or services should behave is critical for designing positive experiences.

Human Resources (HR): HR professionals deal with organizational culture, employee relations, and diversity and inclusion initiatives, all of which are deeply intertwined with workplace norms. Shaping a positive and productive company culture often involves understanding and influencing these norms.

Public Policy Analysis and Implementation: Policymakers and analysts who understand how social norms affect public behavior can design more effective interventions and predict public responses to new laws or programs. This is relevant in areas like public health, environmental protection, and criminal justice.

International Relations and Development: Working across cultures requires a keen sensitivity to differing social norms. Professionals in diplomacy, international aid, and global business must navigate these differences effectively to build relationships and achieve objectives.

Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) Consulting/Management: DEI work inherently involves challenging existing discriminatory norms and fostering new norms of inclusivity and equity within organizations and society.

Public Health: Professionals in this field often use social norms marketing and other norm-based strategies to promote healthy behaviors and prevent disease.

Urban Planning and Community Development: Creating livable and vibrant communities involves understanding the social norms that govern public space usage, neighborhood interactions, and civic participation.

Education: Educators work with classroom and school-wide norms that affect student learning, behavior, and social development.

How Understanding Norms Contributes to Success

In these roles, an understanding of social norms contributes to success in several ways:

More Effective Communication: Knowing the normative expectations of an audience allows for more persuasive and culturally sensitive communication. Whether it's a marketing message, a public health announcement, or a diplomatic negotiation, tailoring communication to align with or thoughtfully address existing norms increases its impact.

Better Prediction of Behavior: An grasp of prevailing descriptive and injunctive norms helps in anticipating how individuals or groups are likely to respond to different situations, products, or policies.

Improved Strategy Design: Professionals can design more effective strategies for behavior change, whether it's encouraging consumers to buy a product, citizens to adopt a health practice, or employees to collaborate more effectively. This might involve reinforcing positive existing norms, correcting misperceptions, or working to shift harmful norms.

Enhanced Cross-Cultural Competence: For roles involving international or diverse domestic populations, understanding and respecting varying social norms is crucial for building trust, avoiding misunderstandings, and fostering effective collaboration.

Fostering Positive Change: In fields like public policy, DEI, and community development, a nuanced understanding of how norms are formed and changed is essential for designing interventions that lead to lasting positive social transformation.

Potential Entry Points and Career Progression

Entry into these fields typically requires a relevant educational background, often a bachelor's degree in a related discipline such as sociology, psychology, marketing, communications, public health, political science, or anthropology. For more specialized or research-oriented roles, a master's or doctoral degree may be necessary.

Entry-level positions might include roles like research assistant, marketing coordinator, HR generalist, policy analyst, community outreach specialist, or UX researcher. As individuals gain experience and demonstrate their ability to apply their understanding of social norms effectively, they can progress to more senior roles involving strategy development, team leadership, program management, or specialized consulting.

For those looking to pivot, highlighting transferable skills such as analytical thinking, communication, empathy, and an understanding of human behavior can be beneficial. Supplementing existing qualifications with online courses or certifications in areas like behavioral science, UX research, or public health can also strengthen a candidate's profile. Networking within the desired field and seeking out projects or volunteer opportunities that allow one to apply knowledge of social norms can also create pathways.

It is important to remember that while the path may seem challenging, especially during a career transition, persistence and a willingness to continuously learn are key. Grounding yourself in the realities of the field while maintaining an encouraging outlook will be beneficial. Every small step and milestone achieved contributes to the larger journey.

Combining Norms Knowledge with Other Skills

While a sophisticated understanding of social norms is a valuable asset, it is often most powerful when combined with other domain-specific skills and knowledge. For example:

A UX researcher who understands social norms will be even more effective if they also possess strong skills in research methodologies, data analysis, and user interface design principles.

A marketing professional's knowledge of consumer norms is amplified by skills in market research, branding, digital marketing tools, and creative campaign development.

A public policy analyst who understands how norms influence policy acceptance will be more impactful if they also have strong analytical skills, knowledge of relevant legislation, and the ability to conduct cost-benefit analyses.

Therefore, aspiring professionals should aim to develop both a deep understanding of social dynamics, including norms, and the specific technical or professional competencies required in their chosen field. This combination creates a versatile and highly sought-after skill set. OpenCourser can be a valuable resource for finding courses that help develop these complementary skills, allowing learners to build a well-rounded profile. For instance, one might explore courses in Data Science to complement social science knowledge, or delve into Marketing or Public Policy for more domain-specific skills.

This book provides an interesting take on how societal structures, including norms, can influence individual achievement.

Frequently Asked Questions (Career Focus)

Navigating a career path related to the understanding and application of social norms can bring up many questions. Here are some frequently asked questions that students, career explorers, and even recruiters might have.

What majors best prepare for careers using social norms knowledge?

Several majors provide a strong foundation. Sociology and Social Psychology are perhaps the most direct, as they explicitly study group behavior, social influence, and the formation and function of norms. Anthropology offers crucial cross-cultural perspectives on norms. Behavioral Economics or Economics with a behavioral focus is excellent for understanding how norms impact decision-making and market behavior.