Transportation Planner

Transportation Planner: Shaping How We Move

Transportation Planners are the architects of movement within our communities. They analyze, design, and manage the systems that allow people and goods to travel efficiently, safely, and sustainably. This field involves looking beyond just roads and cars to encompass public transit, walking, cycling, freight logistics, and the intricate connections between them.

Working as a Transportation Planner means engaging with complex challenges at the intersection of engineering, policy, economics, and social equity. You might find yourself analyzing data to predict future traffic patterns, designing a new bus route to serve an underserved neighborhood, or presenting plans for a new bicycle network to community members. It's a career focused on improving daily life and shaping the future of our cities and regions.

Introduction to Transportation Planning

What is Transportation Planning?

At its core, transportation planning is the process of understanding how people and goods move, anticipating future needs, and developing strategies and infrastructure to meet those needs effectively. It's about creating systems that connect people to jobs, education, services, and recreation, while also facilitating the flow of commerce that underpins our economy.

The scope is broad, covering everything from the design of a single intersection to the development of a long-range regional transportation strategy. Planners consider various modes of travel – driving, public transport, cycling, walking, and freight movement – and how they interact within a complex network.

The goal is to create transportation systems that are safe, efficient, accessible, equitable, and environmentally sustainable. This involves balancing competing demands, such as the need for economic growth with the desire for environmental protection and community well-being.

A Brief History

Historically, transportation planning often focused heavily on accommodating the automobile, particularly after World War II. This led to extensive highway construction and suburban sprawl in many parts of the world. While this improved mobility for some, it also resulted in increased traffic congestion, air pollution, and inequitable access for those without cars.

Over recent decades, the field has evolved significantly. There's now a greater emphasis on multi-modal transportation, recognizing the importance of public transit, walking, and cycling. Sustainability has become a central concern, driving efforts to reduce emissions and reliance on fossil fuels.

Today, planners also grapple with issues of social equity, striving to ensure that transportation investments benefit all communities fairly. The rise of new technologies, like ride-sharing apps and potential autonomous vehicles, presents both opportunities and challenges that continue to shape the field.

Role in Urban and Rural Development

Transportation infrastructure is the backbone of both urban and rural areas. Well-planned transportation systems support economic vitality by connecting workers to jobs, businesses to suppliers and customers, and goods to markets. Access to reliable transportation is crucial for accessing essential services like healthcare and education.

In urban areas, transportation planning shapes land use patterns and influences the character of neighborhoods. Efficient public transit and safe walking/cycling routes can reduce traffic congestion, improve air quality, and create more livable, vibrant communities. Planners work to integrate transportation with land use decisions to promote smart growth and avoid sprawl.

In rural regions, transportation planning addresses challenges like connecting dispersed populations, supporting agriculture and tourism, and maintaining infrastructure over large geographic areas. Ensuring safe and reliable access is vital for the economic health and quality of life in these communities.

An Interdisciplinary Field

Transportation planning is inherently interdisciplinary, drawing knowledge and methods from various fields. Engineering principles are essential for designing roads, bridges, and transit systems. Urban planning provides the context for how transportation fits within the broader fabric of a city or region.

Economics informs decisions about funding, cost-benefit analysis, and the economic impacts of transportation projects. Policy analysis and political science are crucial for navigating the regulatory landscape, understanding governance structures, and implementing plans effectively.

Environmental science helps assess the environmental impacts of transportation systems and develop sustainable solutions. Sociology and geography contribute understanding of travel behavior, demographics, and spatial patterns. Increasingly, data science and computer modeling play vital roles in analyzing complex systems and predicting future trends.

Transportation Planner: Core Responsibilities

Designing Sustainable Transportation Systems

A key responsibility is designing transportation systems that are environmentally friendly, socially equitable, and economically viable for the long term. This involves planning networks that prioritize sustainable modes like public transit, walking, and cycling, alongside managing road networks efficiently.

Planners develop strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, such as promoting electric vehicles, improving fuel efficiency, and designing infrastructure that supports low-carbon travel. They might work on expanding bus rapid transit lines, creating protected bike lanes, or improving pedestrian walkways and access to transit stations.

Sustainability also means considering the entire lifecycle of infrastructure, resilience to climate change impacts, and minimizing negative effects on natural habitats and communities. It requires a holistic view that integrates transportation with land use, energy, and environmental planning.

This course provides insight into sustainable approaches in urban settings.

Analyzing Traffic Patterns and Demographic Data

Understanding current and future travel demand is fundamental. Planners collect and analyze vast amounts of data on traffic volumes, travel times, origins and destinations, mode choices, and population demographics. This data informs decisions about where investments are needed and what types of solutions are most appropriate.

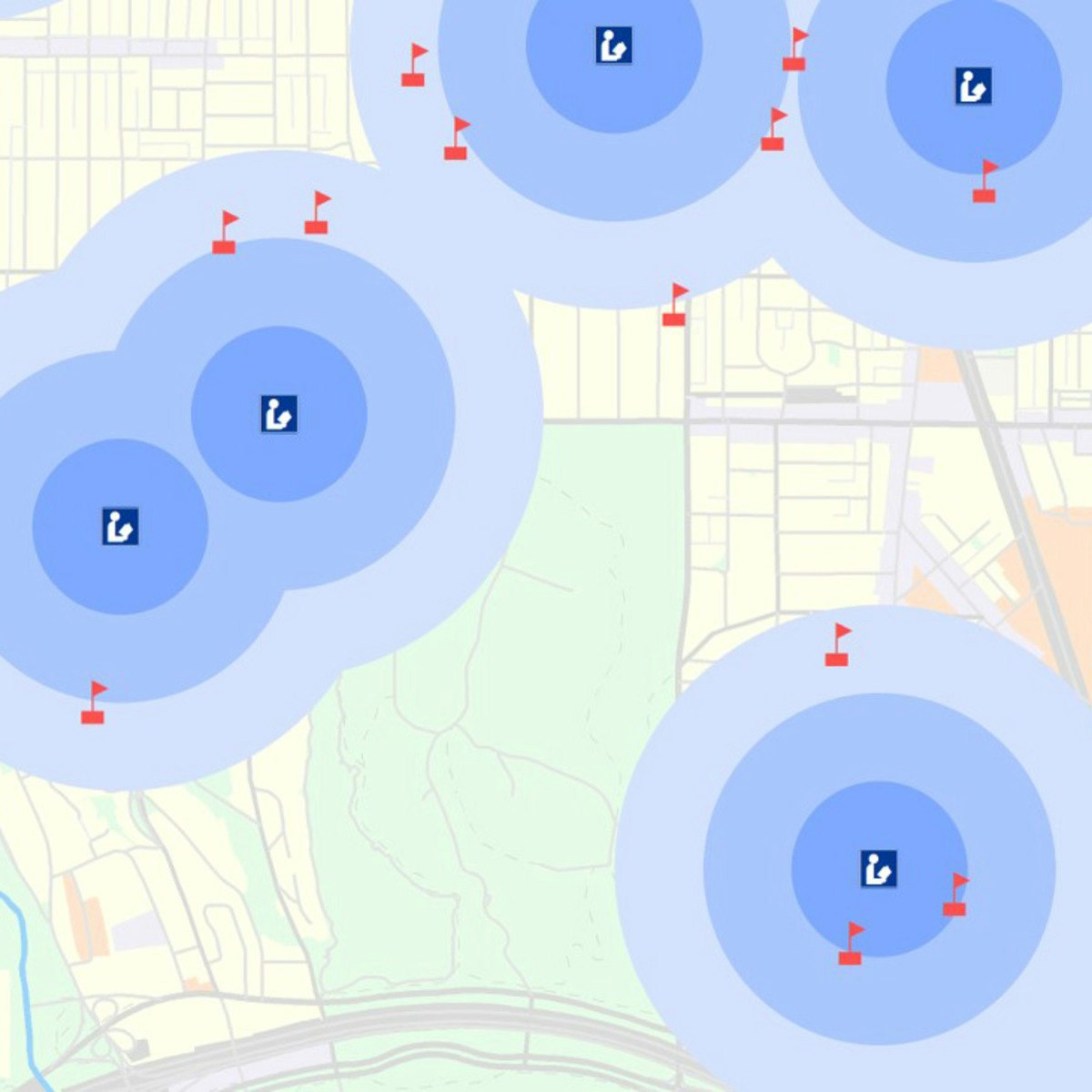

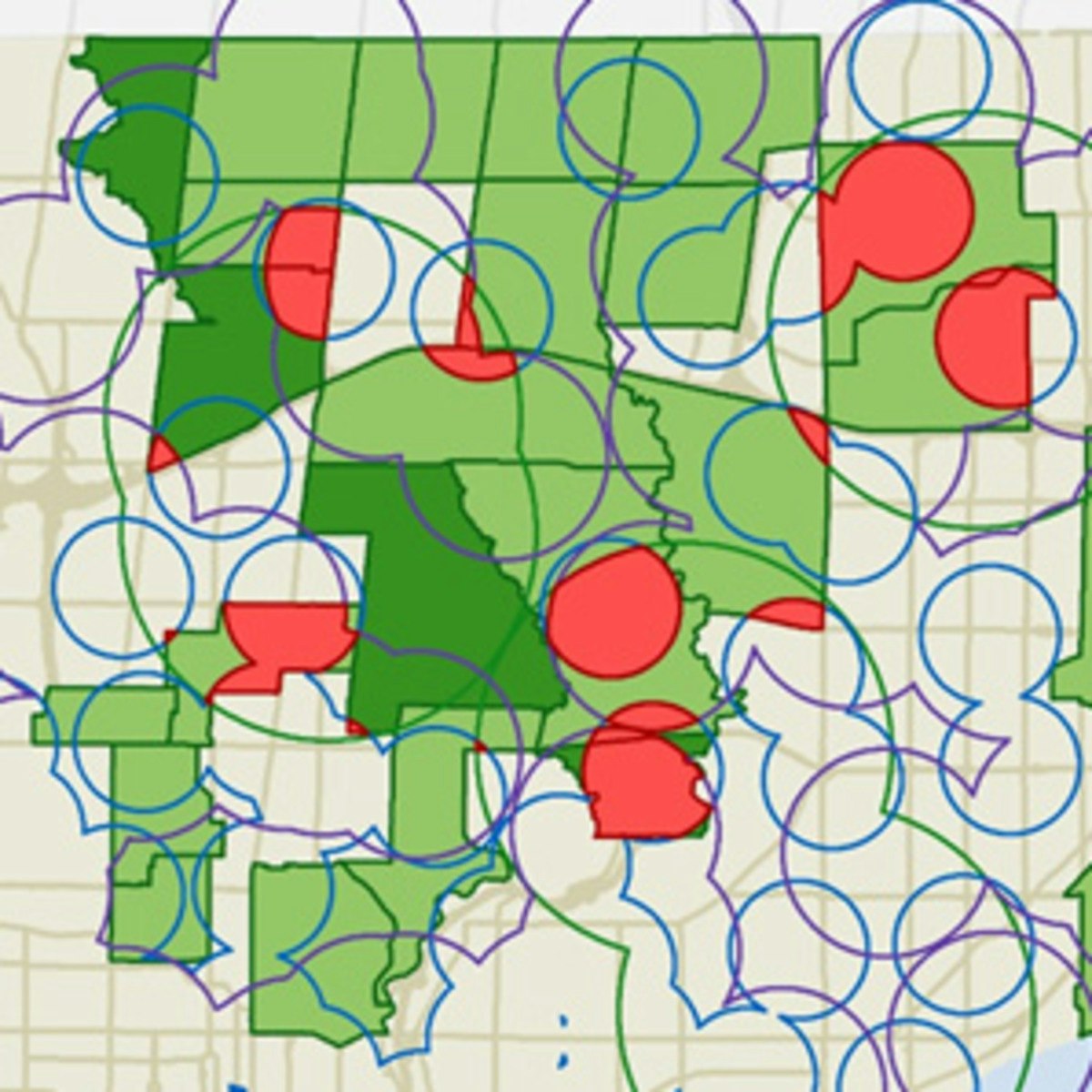

Tools like Geographic Information Systems (GIS) are essential for mapping and analyzing spatial patterns in travel behavior and infrastructure. Statistical analysis and transportation modeling software help forecast future conditions under different scenarios, such as population growth or the introduction of a new transit service.

This analytical work involves identifying congestion hotspots, evaluating the performance of the existing network, understanding the travel needs of different population groups (e.g., commuters, seniors, low-income residents), and assessing the potential impacts of proposed projects.

These courses introduce methods for analyzing transportation systems and traffic flow.

Public Engagement and Stakeholder Collaboration

Transportation projects significantly impact communities, so effective public engagement is crucial. Planners must communicate complex information clearly to diverse audiences, including residents, business owners, elected officials, and community groups.

This involves organizing and facilitating public meetings, workshops, and online forums to gather feedback and build consensus. Planners need strong communication, listening, and negotiation skills to understand different perspectives, address concerns, and incorporate public input into the planning process.

Collaboration extends to working closely with other government agencies (e.g., public works, environmental protection), private developers, transit operators, and advocacy organizations. Building strong working relationships and navigating political dynamics are essential for successful project implementation.

Regulatory Compliance and Policy Implementation

Transportation planners operate within a framework of local, regional, state, and federal regulations. They must ensure that plans and projects comply with environmental laws (like NEPA in the US), safety standards, accessibility requirements (like the ADA), and civil rights legislation.

Planners are often involved in developing transportation policies, such as parking regulations, transit fare structures, or complete streets policies that prioritize safety for all users. They also play a role in securing funding for projects through grant applications and budget processes.

This requires a thorough understanding of the relevant laws and regulations, as well as the ability to navigate bureaucratic processes and write clear, defensible reports and policy documents.

This book explores the policy aspects shaping transportation.

Formal Education Pathways

Relevant Undergraduate Degrees

A bachelor's degree is typically the minimum requirement to enter the transportation planning field. Common undergraduate majors include Urban Planning, Civil Engineering, Geography, Environmental Studies, Public Policy, or Economics.

An Urban Planning degree provides a broad understanding of city systems, land use, and community development, often including specific transportation courses. Civil Engineering offers a strong technical foundation in infrastructure design and analysis, which can be specialized towards transportation.

Degrees in Geography often develop strong spatial analysis (GIS) skills, while Environmental Studies emphasizes sustainability. Public Policy or Economics degrees build skills in policy analysis, evaluation, and understanding regulatory frameworks. Regardless of the major, coursework in statistics, GIS, and communication is highly beneficial.

Graduate Programs and Specialized Certifications

While a bachelor's degree can open doors to entry-level positions, a master's degree is often preferred, and sometimes required, for career advancement and more specialized roles. Common graduate degrees include a Master of Urban Planning (MUP), Master of Science (MS) in Civil Engineering (with a transportation focus), or a Master of Public Policy (MPP).

These graduate programs offer deeper dives into transportation modeling, policy analysis, sustainable transportation, transit planning, and other specialized areas. They also provide opportunities for research and more extensive project work.

Professional certification, while not always mandatory, can enhance credibility and career prospects. The most recognized certification in the US is the American Institute of Certified Planners (AICP), offered by the American Planning Association. Achieving AICP certification requires meeting specific education and experience requirements and passing an exam.

This book offers guidance for those considering a career in urban planning.

Key Coursework

Regardless of the specific degree path, certain subject areas are fundamental to transportation planning. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) is a critical tool for spatial analysis and mapping, and proficiency is expected in most roles.

Courses in statistics and quantitative methods are essential for data analysis and understanding research. Transportation-specific courses cover topics like transportation planning principles, traffic engineering, transportation economics, transit operations, and system modeling.

Understanding policy and law is also vital. Coursework in environmental policy and law, land use law, public finance, and policy analysis provides necessary context. Strong writing and communication skills are paramount, so courses focusing on technical writing and public speaking are valuable.

These courses cover essential GIS and spatial analysis skills frequently used by transportation planners.

Internships and Cooperative Education

Practical experience is invaluable for launching a career in transportation planning. Internships and cooperative education (co-op) programs provide opportunities to apply academic knowledge in real-world settings, build professional networks, and gain exposure to the day-to-day work of planners.

Opportunities can be found in various organizations, including municipal planning departments, regional transportation agencies, state departments of transportation, metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs), private consulting firms, and non-profit advocacy groups.

These experiences allow students to work on actual planning projects, learn industry-standard software, understand organizational dynamics, and potentially secure a job offer upon graduation. Actively seeking out internships during undergraduate or graduate studies is highly recommended.

Online Learning and Skill Development

Digital Tools for Self-Paced Learning

The rise of online learning platforms offers unprecedented access to courses and resources relevant to transportation planning. Self-paced online courses allow learners to acquire foundational knowledge or specialized skills on their own schedule, making it ideal for busy students, working professionals, or career changers.

Platforms like OpenCourser aggregate offerings covering essential areas like GIS software (ArcGIS, QGIS), data analysis (Python, R, Excel), statistics, and introductory concepts in urban planning and transportation.

This flexibility allows individuals to fill knowledge gaps, learn new software, or explore specific interests like sustainable transportation or traffic simulation without enrolling in a full-time degree program. OpenCourser makes it easy to search and compare courses from various providers.

These courses offer introductions to GIS and related tools, suitable for self-paced learning.

Micro-Credentials vs. Traditional Degrees

Online courses often lead to certificates or micro-credentials upon completion. These can be valuable additions to a resume, demonstrating specific competencies or initiative in continuous learning. They are particularly useful for professionals looking to upskill or for career changers needing to prove proficiency in a new area like GIS.

However, it's crucial to have realistic expectations. While micro-credentials can supplement a profile, they typically do not replace a formal bachelor's or master's degree, especially for initial entry into the planning profession where foundational knowledge and accredited qualifications are often expected by employers.

Think of online certificates as tools to enhance your qualifications or bridge specific skill gaps, rather than a substitute for the comprehensive education provided by a university degree. Combining formal education with targeted online learning can be a powerful strategy.

Portfolio-Building Through Independent Projects

One of the best ways to leverage online learning, especially for those without direct work experience, is to build a portfolio of independent projects. After completing an online course on GIS, for example, apply those skills to analyze a local transportation issue, map demographic data related to transit access, or visualize traffic accident patterns.

These projects demonstrate practical application of learned skills and provide tangible evidence of your abilities to potential employers. Document your process, methodologies, and findings clearly. A well-crafted portfolio piece can be far more convincing than simply listing a completed course.

Consider creating an online portfolio or using platforms like GitHub to showcase your work. This proactive approach shows initiative and passion for the field, which can significantly strengthen your job applications.

This capstone course guides learners through completing their own GIS project, ideal for portfolio building.

Complementing Formal Education with Online Resources

Even for those enrolled in traditional degree programs, online resources offer valuable supplements. University courses may not cover the latest version of a specific software or delve deeply into a niche topic like transportation demand modeling or public engagement techniques.

Online courses can fill these gaps, allowing students to tailor their learning to specific career interests or job market demands. They can also provide alternative perspectives or teaching styles that might resonate better with individual learning preferences. Professionals can use them to stay current with evolving technologies and best practices.

OpenCourser's Learner's Guide offers tips on how to integrate online learning effectively, whether you're a student, professional, or lifelong learner. For those mindful of budget, check the OpenCourser deals page for potential savings on courses.

Transportation Planner Career Progression

Entry-Level Roles

Graduates typically start in entry-level positions such as Planning Technician, Transportation Analyst, or Planner I. In these roles, responsibilities often involve supporting senior planners with data collection, basic GIS mapping, research, preparing materials for public meetings, and drafting sections of reports.

This stage focuses on developing foundational skills, learning organizational processes, and gaining exposure to different aspects of transportation planning projects. It's a crucial period for understanding the practical application of theoretical knowledge.

Employers at this level include city and county planning departments, regional transportation agencies, state DOTs, MPOs, and consulting firms. Strong analytical, communication, and software skills (especially GIS) are key.

Mid-Career Specialization

After several years of experience, planners often begin to specialize. Common areas include public transit planning, bicycle and pedestrian planning (active transportation), freight and logistics planning, transportation modeling, traffic operations, or environmental planning related to transportation.

Mid-career roles like Planner II/III, Transportation Planner, or Project Manager involve greater responsibility, including managing smaller projects or specific components of larger ones, conducting more complex analyses, leading public outreach efforts, and mentoring junior staff.

This stage often involves pursuing advanced training or certifications, like the AICP, to solidify expertise and advance professionally. Strong project management and more sophisticated analytical skills become increasingly important.

Leadership Positions

With significant experience and demonstrated expertise, planners can move into leadership roles. These might include Senior Planner, Principal Planner, Project Director, Planning Manager, or Director of Transportation Planning within a public agency.

In consulting firms, leadership paths can lead to Principal, Practice Lead, or Vice President roles. These positions involve managing large, complex projects, supervising teams of planners and analysts, developing strategic plans, managing budgets, interacting with elected officials and high-level stakeholders, and setting departmental or firm-wide direction.

Strong leadership, strategic thinking, political acumen, financial management, and advanced communication skills are essential at this level. Many in leadership roles hold master's degrees and professional certifications.

Alternative Paths in Consulting or Academia

The skills and knowledge gained in transportation planning open doors to related fields. Many planners transition between public sector agencies and private consulting firms throughout their careers. Consulting offers opportunities to work on diverse projects for various clients across different geographies.

Some experienced planners pursue careers in academia, conducting research on transportation issues, publishing scholarly work, and teaching the next generation of planners. This typically requires a Ph.D. and a strong research record.

Other alternative paths include working for non-profit advocacy organizations focused on transportation or environmental issues, roles in real estate development related to transit-oriented development, or positions in technology companies developing mobility solutions.

Tools and Technologies

GIS Software

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) are indispensable tools for transportation planners. Think of GIS as intelligent mapping software that links geographic locations (like roads, transit stops, or neighborhoods) with databases of information (like traffic volumes, population density, or accident data).

Planners use GIS for a wide range of tasks: visualizing existing conditions, analyzing spatial patterns, identifying areas with poor transit access, modeling the impact of new developments on the transportation network, and creating maps for reports and public presentations.

Industry-standard software includes Esri's ArcGIS suite (including ArcGIS Pro and ArcGIS Online) and the open-source alternative QGIS. Proficiency in at least one major GIS platform is a core skill for virtually all transportation planning roles.

These courses provide training in widely used GIS software.

Transportation Simulation Tools

To predict how changes might affect traffic flow and network performance, planners often use specialized transportation modeling and simulation software. These tools create virtual representations of transportation networks and simulate the movement of vehicles and people under different conditions.

Software like PTV Vissim, PTV Visum, Aimsun, or TransCAD allows planners to test scenarios, such as the impact of adding a new highway lane, changing traffic signal timing, introducing a new bus route, or estimating future congestion based on population growth.

These simulations help evaluate the effectiveness of proposed projects, optimize system operations, and provide quantitative data to support decision-making. Familiarity with modeling concepts and specific software packages can be a valuable specialization.

These courses cover simulation techniques relevant to transportation and logistics.

Data Analysis Platforms

Transportation planning is increasingly data-driven. Planners work with large datasets from traffic counts, travel surveys, census data, GPS traces, and other sources. Proficiency in data analysis tools is essential for extracting meaningful insights.

Spreadsheet software like Microsoft Excel is commonly used for basic data manipulation and analysis. Databases and query languages like SQL are important for managing larger datasets.

For more advanced analysis, statistical programming languages like Python (with libraries like Pandas, GeoPandas) and R are becoming standard. These tools offer powerful capabilities for data cleaning, statistical modeling, machine learning, and visualization, enabling more sophisticated analyses of complex transportation phenomena.

This course teaches data visualization, a key skill for presenting analysis results.

Emerging Technologies

The field is constantly evolving with new technologies. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning are being applied to traffic prediction, signal control optimization, and analyzing complex travel patterns from big data sources.

Internet of Things (IoT) sensors embedded in infrastructure provide real-time data on traffic flow, parking availability, and environmental conditions. Data visualization platforms help communicate complex data effectively to stakeholders.

Planners need to stay aware of these emerging technologies and understand their potential applications and implications for transportation systems and planning practices. Lifelong learning is key to remaining current in this dynamic field.

Ethical Considerations in Transportation Planning

Equity in Infrastructure Access

Transportation decisions have profound equity implications. Historically, infrastructure projects like highways have sometimes displaced or disadvantaged low-income communities and communities of color. Planners have an ethical responsibility to ensure that transportation systems provide fair access to opportunities for everyone, regardless of income, race, age, or ability.

This involves analyzing how proposed projects might affect different groups, prioritizing investments in underserved areas, ensuring affordable fares for public transit, and complying with accessibility standards like the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Engaging meaningfully with diverse communities is essential to understand their needs and concerns and to ensure that planning processes are inclusive and lead to equitable outcomes. Planners must advocate for fairness and challenge systemic inequalities embedded in transportation systems.

Environmental Justice Implications

Closely related to equity is environmental justice – the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies. Transportation infrastructure can disproportionately expose certain communities to negative environmental impacts like air pollution, noise, and habitat disruption.

Planners must assess these potential impacts rigorously and seek ways to mitigate harm, particularly in communities already overburdened by environmental hazards. This could involve choosing less impactful alignments for new roads, implementing noise barriers, investing in electric transit fleets, or creating green buffers.

Promoting sustainable transportation modes like walking, cycling, and public transit inherently supports environmental justice goals by reducing overall pollution and providing cleaner mobility options for all.

Balancing Economic Growth with Sustainability

Transportation investments often aim to stimulate economic growth by improving connectivity and facilitating commerce. However, planners face the ethical challenge of balancing these economic objectives with environmental sustainability and community quality of life.

A new highway might reduce commute times and support business development, but it could also increase sprawl, contribute to climate change through higher emissions, and destroy valuable ecosystems. Planners must weigh these trade-offs carefully, considering long-term consequences.

This involves using comprehensive evaluation methods that account for environmental and social costs, not just economic benefits. It requires advocating for solutions that achieve multiple goals, such as transit-oriented development which can support economic activity while reducing car dependency.

Privacy Concerns in Data Collection

Modern transportation planning relies heavily on data, much of which comes from individuals' movements – through smartphone apps, GPS devices, transit fare cards, and vehicle sensors. While this data enables powerful analysis, it also raises significant privacy concerns.

Planners have an ethical obligation to handle this data responsibly. This includes ensuring data is anonymized and aggregated appropriately to protect individual identities, being transparent about data collection practices, and implementing robust security measures to prevent breaches.

Balancing the benefits of data-driven planning with the fundamental right to privacy requires careful consideration and adherence to ethical guidelines and data protection regulations. Planners must be stewards of data, using it only for legitimate planning purposes and safeguarding it diligently.

This book touches upon technologies sometimes used in data collection that raise privacy questions.

Global Opportunities and Challenges

Demand Variations Across Nations

The challenges and priorities in transportation planning vary significantly between developed and developing nations. In rapidly urbanizing countries, the focus might be on building basic infrastructure – roads, bridges, ports, and foundational public transit systems – to keep pace with population growth and economic development.

In contrast, developed nations often grapple with managing congestion in mature networks, maintaining aging infrastructure, reducing environmental impacts, and integrating new technologies like electric and autonomous vehicles. The emphasis shifts towards optimization, sustainability, and enhancing existing systems.

Planners working internationally must understand these differing contexts and tailor their approaches accordingly. Solutions effective in one region may not be suitable or feasible in another due to differences in economic capacity, institutional structures, and travel patterns.

These courses explore urban planning challenges in different global contexts.

Cultural Adaptation in Planning Practices

Effective transportation planning requires sensitivity to local cultural norms, social structures, and political contexts. Planning processes developed in one country may need significant adaptation to work effectively elsewhere.

Public participation methods, decision-making structures, land ownership patterns, and attitudes towards different modes of transport can vary widely. For instance, the role of informal transportation services (like minibuses or motorcycle taxis) is far more significant in some regions than others.

Planners working in diverse cultural settings need strong cross-cultural communication skills, humility, and a willingness to learn from local experts and communities. Imposing external models without adaptation is often ineffective and can lead to unintended negative consequences.

This book examines informal economies, which often include informal transport systems.

Climate Change Adaptation Strategies

Climate change poses a universal challenge, requiring transportation planners globally to develop adaptation strategies. Rising sea levels threaten coastal infrastructure, extreme heat can damage roads and rails, and more intense storms can cause flooding and disruptions.

Planners must incorporate climate projections into long-range planning and infrastructure design. This involves identifying vulnerable assets, developing protective measures (like elevating roads or building sea walls), planning resilient networks with redundancy, and incorporating green infrastructure to manage stormwater.

Simultaneously, planners play a crucial role in climate change mitigation by promoting low-carbon transportation options. This global imperative requires coordinated action across borders and adaptation of best practices to local conditions.

International Certification Reciprocity

For planners seeking opportunities abroad, understanding how professional qualifications are recognized internationally is important. While core planning principles are universal, specific regulations, standards, and certification requirements differ by country.

Certifications like the AICP (US) or RTPI (UK) are highly respected but may not automatically grant the right to practice in another country. Planners may need to undergo additional assessments, examinations, or fulfill specific residency or experience requirements to gain local credentials.

Investigating the specific requirements of the target country well in advance is crucial for those considering an international career move. Professional planning organizations often have information or agreements regarding reciprocity.

Future of Transportation Planning

Impact of Autonomous Vehicles

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) have the potential to fundamentally reshape transportation. Proponents suggest AVs could increase road capacity, improve safety, and enhance mobility for those unable to drive. However, significant uncertainties and challenges remain.

Planners grapple with questions about how AVs will integrate with existing infrastructure, their impact on traffic congestion (potentially increasing vehicle miles traveled), implications for parking demand, effects on public transit ridership, cybersecurity risks, and ethical considerations in accident scenarios.

Planning for an AV future requires flexibility and scenario-based thinking, focusing on managing the transition and shaping policies to ensure AVs contribute positively to broader community goals like sustainability and equity, rather than exacerbating existing problems.

These courses explore the future of mobility, including autonomous systems.

Decarbonization Initiatives

Addressing climate change is a defining challenge, and decarbonizing the transportation sector is critical. This involves a multi-pronged approach: accelerating the transition to electric vehicles (EVs), improving the efficiency and attractiveness of public transit, and making walking and cycling safer and more convenient.

Planners are central to these efforts. They work on planning EV charging infrastructure, designing transit priority measures, expanding bicycle lane networks, implementing policies that discourage single-occupancy vehicle use, and integrating transportation and land use planning to reduce travel distances.

The goal is a systemic shift towards a low-carbon mobility system. This requires significant investment, policy innovation, and behavioral change, all areas where transportation planners play a key role.

Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) Trends

Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) refers to the integration of various transportation services (public transit, ride-sharing, bike-sharing, car-sharing, etc.) into a single digital platform. Users can plan, book, and pay for trips combining multiple modes through one interface.

MaaS has the potential to offer convenient, personalized mobility solutions, potentially reducing reliance on private car ownership. However, it also raises questions about data privacy, market regulation, potential impacts on public transit agencies (both positive and negative), and ensuring equitable access for those without smartphones or bank accounts.

Planners are involved in understanding MaaS ecosystems, developing policies to guide their implementation, and exploring how MaaS can be leveraged to support public policy goals like sustainability and accessibility.

Workforce Automation Risks/Opportunities

Like many fields, transportation planning is being affected by automation and AI. Routine tasks like basic data analysis, traffic counting, or map generation may become increasingly automated. This could free up planners to focus on more complex, strategic, and creative aspects of their work, such as stakeholder engagement, policy development, and long-range visioning.

However, it also means that planners need to adapt and acquire new skills. Proficiency in data science, understanding AI applications, and strong soft skills (communication, collaboration, critical thinking) will become even more crucial. The planners who thrive will be those who can leverage technology effectively while providing the human judgment and context that machines cannot.

While some tasks may be automated, the need for skilled professionals who can navigate complex social, political, and technical challenges to shape our transportation future remains strong.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I transition from civil engineering to transportation planning?

Yes, transitioning from civil engineering to transportation planning is a common and often smooth pathway. Civil engineering provides a strong technical foundation in infrastructure design, analysis, and project management relevant to transportation.

Engineers looking to pivot may benefit from additional coursework or a graduate degree in urban planning or transportation planning to gain a broader understanding of policy, land use, economics, and social equity aspects. Developing skills in GIS, transportation modeling, and public engagement can also facilitate the transition.

Many roles, particularly in transportation engineering sub-fields like traffic operations or infrastructure design, bridge both disciplines. Highlighting transferable skills and potentially pursuing AICP certification can further solidify a career in planning.

What soft skills are most valuable?

Beyond technical expertise, several soft skills are crucial for success. Communication is paramount – the ability to explain complex technical information clearly to diverse audiences (public, politicians, colleagues) both verbally and in writing is essential.

Collaboration and teamwork are vital, as planners constantly work with colleagues from different disciplines, government agencies, consultants, and community members. Strong analytical and problem-solving skills are needed to diagnose issues and develop effective solutions.

Negotiation, facilitation, and conflict resolution skills are important for navigating disagreements and building consensus during public engagement and project development. Adaptability and critical thinking are also key in this evolving field.

How does public sector vs. private sector work differ?

Public sector planners typically work for government agencies (city, county, regional, state, federal). Their focus is often on long-range planning, policy development, regulatory compliance, and managing public projects and infrastructure. Work can be influenced by political cycles and public funding constraints, but offers opportunities to shape community development directly.

Private sector planners usually work for consulting firms hired by public agencies or private developers. The work is often project-based, deadline-driven, and may involve a wider variety of project types and locations. Consultants focus on specific analyses, design tasks, environmental reviews, or public outreach for clients. The pace can be faster, but influence on overarching policy may be less direct.

Salaries and benefits can vary, with consulting sometimes offering higher pay but potentially less job security or different work-life balance compared to government roles. Many planners move between sectors during their careers.

Is licensure/certification required?

For roles focused purely on planning, professional licensure (like a Professional Engineer or PE license) is generally not required, though it can be advantageous, especially if transitioning from engineering. The PE license is essential for engineers who sign off on design plans.

Professional certification, primarily the AICP certification from the American Planning Association, is highly recommended and often preferred or required for advancement in planning roles, particularly in the public sector. It signifies a standard of knowledge, experience, and ethical commitment.

Requirements for AICP include a combination of relevant education and professional planning experience, plus passing a comprehensive exam. Maintaining the certification requires ongoing professional development.

Typical salary ranges at different career stages?

Salary ranges for Transportation Planners vary based on location, sector (public vs. private), experience level, education, and specific responsibilities. Entry-level positions might start in the $50,000 - $70,000 range in many US metropolitan areas.

Mid-career planners with several years of experience and potentially a master's degree or certification might earn between $70,000 and $100,000+. Senior planners and managers in leadership positions can earn well over $100,000, sometimes exceeding $150,000 or more in high-cost-of-living areas or senior roles in large organizations or successful consultancies.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median annual wage for urban and regional planners (which includes transportation planners) was $81,870 in May 2023. Consulting roles may offer higher potential earnings but can also have more variability.

Remote work feasibility in this field?

The feasibility of remote work has increased, but it varies. Many analytical tasks, report writing, and data processing can be done remotely. Virtual meetings are common for internal collaboration and some stakeholder interactions.

However, transportation planning often requires site visits to understand existing conditions, field data collection, and in-person public meetings or workshops for effective community engagement. Therefore, fully remote positions might be less common than hybrid arrangements where planners split time between remote work and the office or field.

Roles heavily focused on data analysis or modeling might offer more remote flexibility than positions requiring frequent site visits or extensive public interaction. Agency or company culture also plays a significant role in remote work policies.

Concluding Thoughts

A career as a Transportation Planner offers the chance to tackle complex problems and make tangible improvements to communities. It requires a blend of analytical rigor, creative problem-solving, communication skills, and a commitment to public service and sustainability. Whether you are designing safer streets for children to walk to school, planning a new light rail line to connect neighborhoods, or analyzing data to reduce traffic congestion, the work directly impacts people's daily lives. While the path involves continuous learning and navigating intricate challenges, it provides a rewarding opportunity to shape a more mobile, equitable, and sustainable future.