Cultural Heritage Manager

A Comprehensive Guide to a Career as a Cultural Heritage Manager

Cultural heritage management is a field dedicated to the preservation, protection, and promotion of the world's diverse cultural legacies. This includes tangible heritage, such as historic sites, monuments, artifacts, and landscapes, as well as intangible heritage like traditions, languages, and local knowledge. Professionals in this interdisciplinary domain work to ensure that these invaluable assets are safeguarded for future generations while also making them accessible and meaningful to contemporary society. It's a career that blends a passion for the past with practical skills in planning, conservation, and community engagement.

Working as a Cultural Heritage Manager can be immensely rewarding. You might find yourself developing strategies to protect ancient ruins from environmental threats, collaborating with local communities to revitalize traditional crafts, or using cutting-edge technology to create virtual experiences of historical sites. The field is dynamic, offering opportunities to engage with diverse cultures, contribute to scholarly research, and shape public understanding and appreciation of our shared human story. The challenge of balancing preservation with accessibility and sustainable development makes this career path both intellectually stimulating and impactful.

What is Cultural Heritage Management All About?

This section delves into the core principles and scope of cultural heritage management, offering a clearer picture of this multifaceted profession.

Defining the Discipline: Scope and Significance

Cultural Heritage Management (CHM) is the vocation and practice of managing cultural heritage in all its forms. It encompasses the identification, interpretation, conservation, and presentation of cultural sites, physical artifacts, and intangible traditions. The scope is broad, ranging from archaeological sites and historic buildings to museum collections, cultural landscapes, and living heritage expressions like music, dance, and oral histories. CHM professionals work at the intersection of various disciplines, including archaeology, history, anthropology, museum studies, conservation science, and public policy.

The significance of cultural heritage management lies in its role in fostering identity, social cohesion, and understanding between different cultures. Heritage provides a tangible link to the past, offering insights into human history, achievements, and challenges. By managing these resources effectively, professionals in the field help communities connect with their roots, promote cultural diversity, and build a shared sense of belonging. Furthermore, well-managed heritage can be a vital resource for education, research, and sustainable tourism, contributing to local economies and enriching lives.

If you're fascinated by the stories embedded in ancient artifacts or passionate about preserving living traditions, cultural heritage management offers a path to translate that interest into meaningful action. OpenCourser provides a wealth of resources to explore this field further, from introductory courses to specialized programs. You can begin by browsing topics like History or Anthropology to build a foundational understanding.

The Evolution of a Protective Field

The concept of actively managing cultural heritage has evolved significantly over time. Early efforts were often focused on the preservation of monumental architecture and elite collections, driven by national pride or scholarly interest. However, the 20th century witnessed a growing international awareness of the vulnerability of heritage, spurred by the destruction caused by world wars and rapid modernization. This led to the development of international conventions and organizations, such as UNESCO, dedicated to the protection of world cultural and natural heritage.

Initially, the emphasis was largely on tangible heritage – the physical remains of the past. However, in recent decades, there has been a paradigm shift to include intangible cultural heritage, recognizing that traditions, knowledge systems, and cultural expressions are equally vital components of a society's legacy. This expanded understanding has broadened the scope of CHM, incorporating community-based approaches and a greater appreciation for cultural diversity. The field now grapples with complex issues like decolonization, repatriation, and the impacts of globalization and climate change on heritage resources.

Modern cultural heritage management also increasingly acknowledges the importance of sustainable practices and community involvement. There's a growing recognition that heritage sites don't exist in a vacuum but are integral parts of living communities and ecosystems. Therefore, successful management strategies often involve collaboration with local stakeholders, ensuring that conservation efforts align with community needs and aspirations.

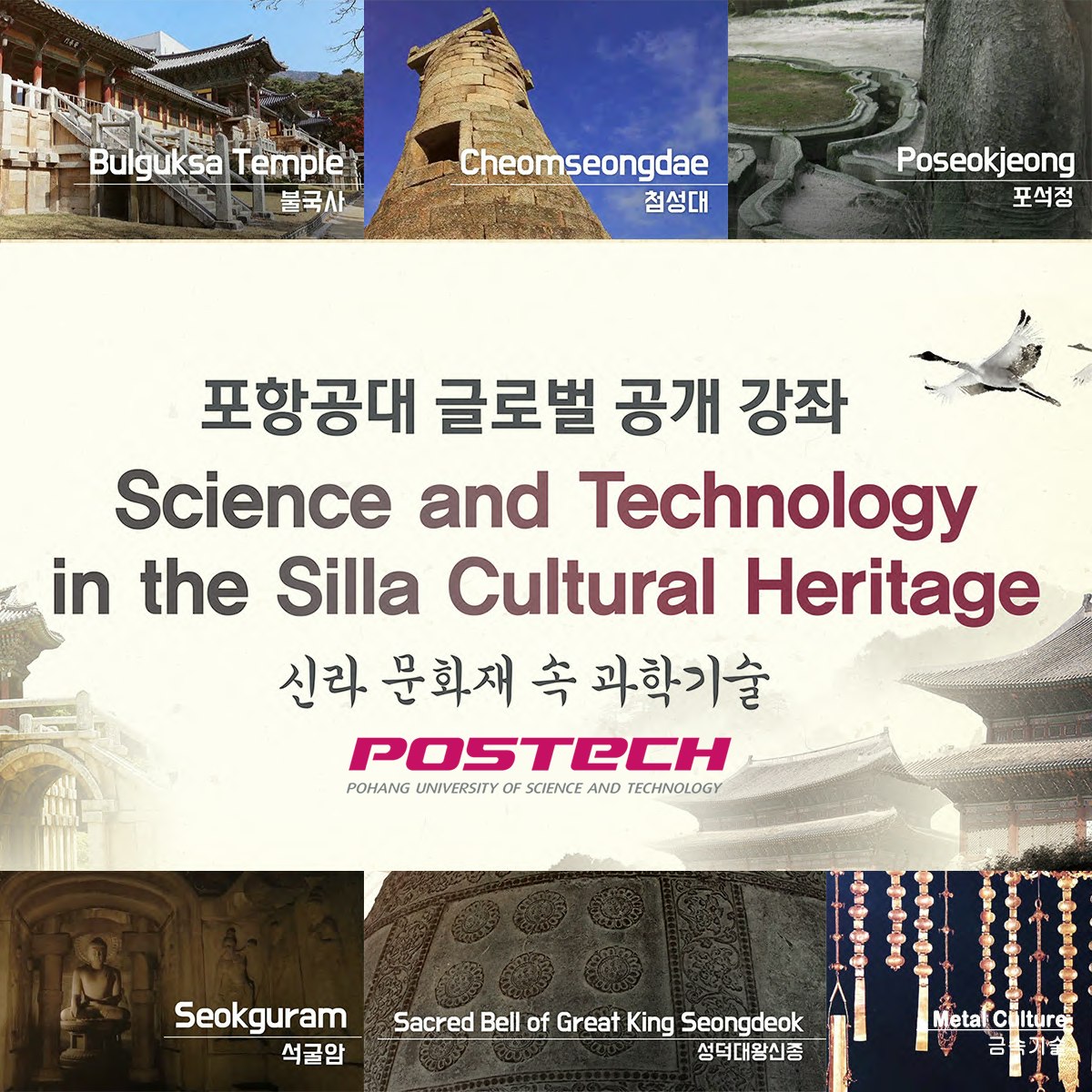

To understand the rich tapestry of cultures that cultural heritage managers work to protect, exploring specific cultural histories can be enlightening. These courses offer glimpses into diverse civilizations and their enduring legacies.

Core Objectives: Preservation, Education, and Accessibility

The primary goals of cultural heritage management revolve around three interconnected pillars: preservation, education, and accessibility. Preservation is paramount, involving the protection of heritage from threats such as decay, damage, neglect, or inappropriate development. This can encompass a wide range of activities, from hands-on conservation treatments for artifacts to developing long-term management plans for historic sites. The aim is to ensure the physical integrity and authenticity of heritage for future generations.

Education plays a crucial role in fostering public understanding and appreciation of cultural heritage. Heritage managers often develop and deliver interpretive programs, exhibitions, and educational materials to communicate the significance of heritage resources to diverse audiences. By sharing the stories and knowledge embedded in heritage, they aim to inspire curiosity, promote learning, and build a sense of connection to the past.

Accessibility ensures that cultural heritage is available for people to experience, learn from, and enjoy. This involves not only physical access to sites and collections but also intellectual and cultural access. Managers strive to remove barriers, whether physical, social, or economic, that might prevent people from engaging with their heritage. This can include developing inclusive programming, utilizing digital technologies to reach wider audiences, and ensuring that heritage interpretation is respectful and representative of diverse perspectives.

The following books offer deeper insights into the principles and practices of managing and interpreting cultural assets.

Interconnections: Archaeology, History, and Public Policy

Cultural Heritage Management is inherently interdisciplinary, drawing heavily from fields like archaeology, history, and public policy. Archaeology provides the methods for discovering, documenting, and understanding past human societies through their material remains. Historical research offers the context and narratives that help interpret these remains and understand their significance over time. Both disciplines are foundational to identifying what constitutes heritage and why it's important to preserve.

Public policy provides the framework for protecting and managing cultural heritage. Laws and regulations at local, national, and international levels govern issues such as site protection, artifact ownership, heritage impact assessments for development projects, and the illicit trafficking of cultural property. Cultural heritage managers must navigate these legal and political landscapes, advocating for heritage and working with government agencies and other stakeholders to ensure compliance and effective stewardship.

The relationship is a two-way street. Insights from heritage management can inform archaeological and historical research by highlighting preservation challenges and the social contexts of heritage. Similarly, the needs and values identified through heritage management can influence the development of more effective and equitable public policies. This collaborative approach is essential for ensuring that heritage is managed in a way that is both scientifically sound and socially responsible.

These courses offer foundational knowledge in areas closely linked to cultural heritage management.

Key Responsibilities of a Cultural Heritage Manager

A Cultural Heritage Manager's role is diverse and demanding, requiring a blend of specialized knowledge, practical skills, and a commitment to safeguarding our collective past. The day-to-day work involves a dynamic interplay of strategic planning, hands-on conservation, community engagement, and navigating complex ethical and technological landscapes.

Site Preservation and Conservation Planning

A core responsibility is the development and implementation of plans for site preservation and conservation. This begins with thorough research and documentation to understand the historical and cultural significance of a site or collection. Managers then assess potential threats, which can range from environmental factors like weathering and climate change to human impacts such as urban development, tourism, or even conflict.

Conservation planning involves devising strategies to mitigate these threats and ensure the long-term survival of heritage assets. This might include physical interventions like stabilizing structures, restoring damaged artifacts, or implementing preventive conservation measures to control environmental conditions. It also involves creating comprehensive management plans that outline protocols for maintenance, monitoring, and emergency preparedness. These plans must often balance the need for preservation with public access and sustainable use.

Understanding the scientific principles behind conservation is crucial. This can involve learning about material science, deterioration processes, and the appropriate application of conservation techniques. Online courses can provide valuable foundational knowledge in these areas, helping aspiring managers grasp the technical aspects of preservation.

These courses delve into the specifics of various cultural heritages and the contexts in which preservation occurs.

Consider these books for a deeper understanding of conservation and heritage management practices.

Collaboration with Stakeholders

Cultural Heritage Managers rarely work in isolation. Effective heritage management requires collaboration with a diverse array of stakeholders. These can include government agencies at local, regional, and national levels, indigenous communities, local residents, private sector developers, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), academic researchers, and international bodies like UNESCO.

Building and maintaining positive relationships with these groups is essential. This involves clear communication, active listening, and a willingness to understand and address different perspectives and interests. For example, working with local communities might involve participatory planning processes to ensure that heritage management aligns with their values and traditions. Collaborating with government agencies is crucial for navigating regulatory frameworks and securing necessary permits and funding.

Negotiation and conflict resolution skills are also important, as competing interests can sometimes arise. A manager might need to mediate between the goals of preservation and the pressures of economic development, or facilitate dialogue between different community groups with varying connections to a heritage site. Successful stakeholder collaboration leads to more sustainable and equitable heritage outcomes.

The ability to work effectively with diverse groups is a key skill. Courses in communication and project management can be highly beneficial.

Ethical Considerations in Artifact Handling and Interpretation

Ethical considerations are at the heart of cultural heritage management, particularly concerning the handling, interpretation, and ownership of artifacts and cultural materials. Managers must grapple with complex questions about who owns the past, whose stories are told, and how heritage should be presented to the public. Issues of provenance (an artifact's history of ownership) and repatriation (the return of cultural property to its country or community of origin) are often central to these discussions.

Respect for cultural sensitivities is paramount, especially when dealing with human remains, sacred objects, or heritage belonging to indigenous or marginalized communities. This requires ongoing dialogue and consultation with relevant groups to ensure that management practices are culturally appropriate and do not perpetuate past injustices. The principle of "do no harm" guides conservation interventions, emphasizing minimal intervention and the reversibility of treatments where possible.

Interpretation also carries significant ethical weight. Managers must strive for accuracy, inclusivity, and transparency in how heritage is presented. This means acknowledging multiple perspectives, addressing difficult or contested histories, and avoiding interpretations that reinforce stereotypes or exclude certain voices. The goal is to foster critical engagement with the past, rather than presenting a single, authoritative narrative.

These courses touch upon the diverse cultural contexts and ethical dimensions inherent in heritage work.

Books exploring ethical frameworks and critical practice in the museum and heritage sector can provide valuable perspectives.

Digital Archiving and Technology Integration

In the 21st century, digital technologies play an increasingly vital role in cultural heritage management. Digital archiving involves creating and managing digital records of heritage assets, from high-resolution images and 3D scans of artifacts and sites to databases of historical information and oral histories. These digital archives serve multiple purposes: they aid in preservation by creating a durable record, facilitate research by making information more accessible, and enable new forms of public engagement.

Technology integration extends beyond archiving. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) are used for mapping and analyzing heritage landscapes. 3D modeling and virtual reality (VR) can create immersive experiences of past environments or inaccessible sites. Digital platforms are also crucial for outreach, education, and online exhibitions, allowing heritage institutions to connect with global audiences. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) even supports the use of nuclear techniques for characterizing and preserving artifacts.

Cultural heritage managers need to be conversant with these digital tools and understand their potential and limitations. This doesn't necessarily mean being an expert in every technology, but it does require the ability to assess which tools are appropriate for specific tasks, manage digital projects, and understand the ethical implications of digital heritage, such as data ownership and accessibility. As technology continues to evolve, a willingness to learn and adapt is essential.

For those interested in the intersection of technology and cultural preservation, courses focusing on digital tools and their application in heritage contexts are highly recommended. OpenCourser's Technology section might offer relevant introductory courses.

The following books explore the use of technology in documenting and managing heritage.

Essential Skills for Cultural Heritage Managers

Becoming a successful Cultural Heritage Manager requires a diverse skill set that combines technical knowledge with strong interpersonal and managerial abilities. Whether you are preserving ancient artifacts or engaging with communities, certain competencies are crucial for navigating the complexities of this field. Many of these skills can be honed through formal education, practical experience, and targeted online courses.

Technical Conservation Knowledge

A fundamental understanding of technical conservation principles and techniques is often essential, especially for roles directly involved in the physical care of heritage objects and sites. This includes knowledge of material science – how different materials like stone, wood, metal, textiles, and ceramics behave and deteriorate over time. It also involves familiarity with various conservation treatments, from cleaning and stabilization to restoration and repair, and knowing when and how to apply them appropriately.

Preventive conservation is another key area, focusing on creating stable environments to slow down deterioration. This might involve controlling temperature, humidity, light exposure, and pests. Understanding risk assessment and disaster preparedness for heritage collections is also increasingly important. While not every heritage manager is a hands-on conservator, a grasp of these technical aspects is vital for making informed decisions, managing conservation projects, and working effectively with specialist conservators.

Many universities offer specialized programs in conservation. Online courses can also provide a solid introduction to conservation science and ethics, helping to build a foundational understanding of these critical technical skills. Exploring platforms like OpenCourser for courses related to conservation science or material science for heritage can be a good starting point.

These courses touch upon the art, architecture, and material culture that managers often work to conserve.

For those interested in the technical aspects of preservation, these books offer valuable insights.

Cross-Cultural Communication and Collaboration

Cultural heritage is deeply intertwined with identity and community. Therefore, the ability to communicate and collaborate effectively across different cultural contexts is a vital skill for heritage managers. This involves more than just language proficiency; it requires cultural sensitivity, empathy, and an understanding of diverse worldviews and communication styles.

Managers often work with local communities, indigenous groups, international partners, and diverse teams. Building trust and rapport, actively listening to different perspectives, and navigating potential cultural misunderstandings are crucial for successful project outcomes and ethical practice. This skill is particularly important in projects involving intangible heritage, where understanding and respecting local traditions and knowledge systems is paramount.

Developing cross-cultural communication skills can involve learning about different cultural norms, practicing active listening, and seeking opportunities for intercultural exchange. Online courses in intercultural communication, anthropology, or sociology can provide valuable frameworks and insights. OpenCourser's Social Sciences category may offer relevant courses.

These courses provide insights into various cultures, which is foundational for effective cross-cultural communication.

Grant Writing and Fundraising Acumen

Many cultural heritage projects and organizations rely heavily on external funding. As such, skills in grant writing and fundraising are often highly valued, and sometimes essential, for Cultural Heritage Managers. This involves identifying potential funding sources, which can include government grants, private foundations, corporate sponsorships, and individual donors.

Successful grant writing requires the ability to articulate a compelling vision for a project, clearly outline its objectives and methodologies, demonstrate its significance and potential impact, and present a realistic budget. Fundraising may also involve developing and managing donor relationships, organizing fundraising events, and creating persuasive campaigns. Strong persuasive writing and communication skills are key, as is meticulous attention to detail in preparing applications and reports.

Even if not directly responsible for writing grants, managers often need to contribute to funding proposals or oversee fundraising efforts. Understanding the funding landscape and the principles of effective fundraising can significantly enhance a manager's ability to secure the resources needed to protect and promote heritage. Online courses on grant writing, nonprofit management, or fundraising can be excellent resources for developing these practical skills. You can explore these on platforms like OpenCourser by searching for "grant writing" or "nonprofit fundraising".

This book can offer insights into the broader context of arts funding and value.

Knowledge of Legal and Regulatory Frameworks

Cultural heritage is protected and managed within a complex web of legal and regulatory frameworks at local, national, and international levels. Cultural Heritage Managers must have a working knowledge of these laws and regulations to ensure compliance, protect heritage assets from illegal activities, and advocate effectively for their preservation.

This includes understanding legislation related to the protection of archaeological sites, historic buildings, and cultural landscapes; laws governing the ownership, excavation, and trade of cultural property; and international conventions such as the UNESCO World Heritage Convention or the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict. Managers may also need to be familiar with environmental laws, planning regulations, and intellectual property rights as they relate to heritage.

While a law degree isn't typically required, an understanding of the legal principles and processes relevant to heritage is crucial. This enables managers to work effectively with legal professionals, government agencies, and law enforcement, and to make informed decisions that uphold both the letter and the spirit of heritage protection laws. Introductory courses on cultural heritage law or policy can be beneficial. For those seeking in-depth knowledge, some master's programs in heritage management offer specialized modules on legal aspects.

These topics touch upon the governance and broader context in which heritage laws operate.

Consider this book for insights into legal aspects of intangible heritage.

Formal Education Pathways to Becoming a Cultural Heritage Manager

Embarking on a career as a Cultural Heritage Manager typically involves a dedicated educational journey. While passion and experience are invaluable, a solid academic foundation provides the theoretical knowledge, research skills, and critical thinking abilities necessary for success in this diverse field. Universities and academic institutions across the globe offer a range of programs tailored to aspiring heritage professionals.

For those considering this path, exploring online course catalogs like OpenCourser can be an excellent first step. You can browse programs, compare curricula, and identify institutions that align with your interests, whether they are in Archaeology, Museum Studies, or broader Heritage Management.

Relevant Undergraduate Degrees

A bachelor's degree is generally the starting point for a career in cultural heritage management. While there isn't always a single prescribed major, several fields provide a strong foundation. Degrees in Archaeology offer training in the methods of uncovering and interpreting past societies through material remains. History programs develop critical research and analytical skills, providing context for understanding heritage.

Anthropology, particularly cultural anthropology, can be very beneficial for understanding the social and cultural dimensions of heritage. Museum Studies or Heritage Studies are increasingly common undergraduate options that offer a more direct introduction to the principles and practices of the field. Other related degrees include Art History, Classics, Geography, or Environmental Studies, depending on your specific area of interest within heritage management.

Regardless of the specific major, coursework that emphasizes research methods, critical thinking, writing skills, and an understanding of cultural diversity will be advantageous. Seeking out universities with faculty who have expertise in heritage-related fields and looking for opportunities for undergraduate research or internships can also greatly enhance your profile.

These courses provide a taste of the diverse subject matter encountered in heritage-related undergraduate studies.

Specialized Master's Programs

For many aspiring Cultural Heritage Managers, a master's degree is a crucial step for specialized training and career advancement. Master of Arts (MA) or Master of Science (MSc) programs in Cultural Heritage Management, Museum Studies, Historic Preservation, or Cultural Resource Management offer focused curricula designed to equip students with the advanced knowledge and practical skills needed in the profession. Johns Hopkins University, for example, offers an online MA in Cultural Heritage Management that covers a broad context of heritage issues. Similarly, programs like those at the University of Sheffield integrate heritage management with aspects of marketing and creative industries management.

These programs often combine theoretical coursework with practical components, such as internships, fieldwork, or research projects. Coursework might cover topics like heritage policy and ethics, conservation principles, collections management, site interpretation, community engagement, and project management. Some programs allow for specialization in areas like digital heritage, intangible heritage, or specific geographical regions. The University of Barcelona's Master's in Cultural Heritage Management and Museology, for instance, prepares students for roles in museums and cultural enterprises.

When choosing a master's program, consider factors such as the program's focus, faculty expertise, opportunities for practical experience, and alumni network. Some programs, like the one offered by the University of Maryland, are designed for working professionals and offer distance learning options. The University of Haifa also provides an international MA program taught in English with a practicum component.

These courses offer a glimpse into the advanced topics and specialized knowledge covered in master's programs.

These books are foundational texts or provide specialized knowledge relevant to postgraduate study in heritage.

Doctoral Research Opportunities

For those interested in pursuing advanced research, academic careers, or high-level policy and leadership roles, a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in a heritage-related field can be a valuable pursuit. PhD programs allow for in-depth investigation of specific topics within cultural heritage management, conservation science, archaeology, anthropology, or related disciplines. This level of study contributes original knowledge to the field and develops expert-level analytical and research skills.

Doctoral research in cultural heritage can span a vast range of subjects, from examining the impacts of climate change on specific World Heritage sites to developing new conservation techniques for ancient materials, or critically analyzing the social and political dimensions of heritage representation. PhD candidates typically work closely with faculty advisors, conduct extensive fieldwork or archival research, and produce a substantial dissertation that makes an original contribution to scholarship.

A PhD is a significant commitment, often requiring several years of intensive study and research. It is generally pursued by individuals with a strong passion for a particular area of heritage and a desire to push the boundaries of knowledge or influence the field at a strategic level. Graduates with PhDs may find opportunities in universities, research institutions, senior positions in museums or heritage organizations, or as specialized consultants.

While OpenCourser primarily lists courses, the topics covered in advanced courses can give an idea of potential research areas.

These books represent the kind of in-depth scholarly work often associated with doctoral-level research.

The Role of Field Schools and Practical Experience

Beyond formal degree programs, field schools and other forms of practical experience are exceptionally important in cultural heritage management. Field schools, particularly common in archaeology and historic preservation, provide intensive, hands-on training in real-world settings. Participants learn practical skills such as excavation techniques, site recording, artifact identification and processing, building documentation, or conservation methods under the guidance of experienced professionals.

Internships and volunteer work offer other invaluable opportunities to gain practical experience and build professional networks. Many museums, heritage sites, conservation labs, and cultural resource management firms offer internships for students and recent graduates. These placements allow individuals to apply their academic knowledge, learn from seasoned practitioners, and gain insight into the day-to-day realities of the profession. Volunteering can also be a significant stepping stone, particularly for those looking to enter the field or explore different areas of specialization.

Such experiences not only develop practical skills but also demonstrate initiative and commitment to potential employers. They can help clarify career interests and provide networking opportunities that may lead to future employment. Many educational programs incorporate or strongly encourage such practical components as part of their curriculum. Accumulating professional experience while still a student can significantly ease the transition into the job market.

Digital Tools Revolutionizing Cultural Heritage Management

The landscape of cultural heritage management is being continually reshaped by technological advancements. Digital tools now offer unprecedented capabilities for documenting, analyzing, preserving, and sharing cultural heritage. For Cultural Heritage Managers, understanding and utilizing these technologies is becoming increasingly essential for effective and innovative practice. These tools not only enhance traditional methods but also open up entirely new avenues for research, conservation, and public engagement.

The integration of digital technologies is a key theme in modern heritage studies. Exploring resources on Digital Humanities or specific software can provide a valuable overview of this evolving aspect of the field.

3D Scanning and Reconstruction Software

Three-dimensional (3D) scanning and reconstruction software have emerged as powerful tools for cultural heritage documentation and analysis. These technologies allow for the creation of highly accurate digital models of artifacts, buildings, and even entire archaeological sites. Laser scanners and photogrammetry (creating 3D models from photographs) capture detailed geometric and textural information, which can then be processed to generate digital twins of heritage assets.

These 3D models have numerous applications. They serve as precise records for conservation purposes, allowing managers to monitor changes over time, assess damage, and plan interventions without physically disturbing the original object or structure. They can be used for research, enabling detailed analysis of construction techniques or artistic details. Furthermore, 3D models are invaluable for public engagement, forming the basis for virtual tours, interactive exhibits, and educational resources, making heritage accessible to a wider audience, including those who cannot visit sites in person.

Familiarity with these tools, or at least an understanding of their capabilities and how to commission and manage such projects, is a growing expectation for heritage professionals. Many universities and specialized training programs now include modules on 3D documentation techniques.

These courses introduce the digital transformation in cultural heritage and related skills.

This book discusses the importance of 3D recording in the field.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) in Heritage Contexts

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) are powerful software tools for capturing, storing, analyzing, and visualizing spatial data. In cultural heritage management, GIS plays a crucial role in understanding the landscape context of heritage sites, managing site information, and assessing risks. Managers can use GIS to map the locations of archaeological sites, historic buildings, and other cultural resources, often integrating this information with environmental data, historical maps, and development plans.

This spatial analysis capability allows for a deeper understanding of settlement patterns, trade routes, and the relationship between heritage sites and their surrounding environment. GIS is also invaluable for site management, helping to track the condition of resources, plan survey and excavation work, and manage visitor access. In terms of risk assessment, GIS can be used to model the potential impacts of natural hazards like floods or erosion, or human activities like urban expansion, on heritage resources.

Proficiency in GIS is a highly sought-after skill in many areas of cultural heritage management, particularly in archaeological survey, cultural resource management (CRM), and landscape studies. Numerous online courses and university programs offer training in GIS applications for heritage. You can often find these by searching for "GIS for archaeology" or "GIS cultural heritage" on educational platforms.

Database Management for Collections and Sites

Effective management of cultural heritage information relies heavily on robust database systems. Whether dealing with museum collections containing thousands of artifacts, archaeological records from numerous excavations, or information about a portfolio of historic buildings, databases are essential for organizing, accessing, and analyzing vast amounts of data. These systems store diverse information, including object descriptions, images, conservation records, provenance details, site locations, and research notes.

Well-designed databases enable efficient cataloging, facilitate research by allowing complex queries, and support collections management tasks such as loan tracking and inventory control. For site management, databases can store information on architectural features, condition assessments, maintenance histories, and visitor statistics. The ability to link different types of data – for example, connecting an artifact record to its find spot on an archaeological site map (often using GIS integration) – enhances the analytical power of these systems.

Cultural Heritage Managers often need to understand database principles, even if they are not database developers themselves. This includes familiarity with data standards, metadata creation, and the ethical considerations of data management, such as privacy and intellectual property. Training in specific collections management software or general database skills can be highly beneficial. Many museum studies and archives programs include coursework in this area.

Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) Applications

Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) are emerging technologies that offer exciting new possibilities for interpreting and experiencing cultural heritage. VR can create fully immersive digital reconstructions of past environments, allowing users to "walk through" ancient cities, explore historic buildings as they once were, or witness historical events. This provides powerful educational and engagement opportunities, making the past more tangible and relatable.

Augmented Reality overlays digital information onto the real world, typically viewed through a smartphone or tablet. For example, visitors at an archaeological site could use an AR app to see a reconstruction of a ruined structure superimposed on the existing remains, or to access additional information about specific features they are looking at. AR can enhance on-site interpretation, providing dynamic and interactive content that goes beyond traditional signage.

While still evolving, these "immersive technologies" are increasingly being explored by museums, heritage sites, and educational institutions. Cultural Heritage Managers who are aware of the potential of VR and AR can contribute to innovative projects that enhance public understanding and appreciation of heritage. While deep technical expertise in developing VR/AR applications may not be required for all managers, an understanding of how these tools can be used effectively for interpretation and outreach is valuable.

This course focuses on adapting cultural heritage for modern audiences, including through digital means.

Career Progression for Cultural Heritage Managers

The career path for a Cultural Heritage Manager can be varied and rewarding, offering opportunities for growth, specialization, and leadership. Progression often depends on a combination of education, experience, skill development, and networking. While some may follow a more traditional trajectory within institutions, others might find fulfilling roles in consultancy, advocacy, or related sectors.

For those starting out, gaining diverse experiences and building a strong professional network are key. Platforms like OpenCourser's list management can help you curate relevant courses and resources to support your career development journey in this field.

Entry-Level Roles and Gaining Experience

Entry into the cultural heritage field often begins with roles such as heritage assistant, museum technician, collections assistant, site interpreter, or field technician in cultural resource management (CRM). These positions provide invaluable hands-on experience in various aspects of heritage work, from cataloging artifacts and assisting with exhibitions to participating in archaeological surveys or conservation tasks. Many professionals gain their initial foothold through internships, volunteer positions, or seasonal work, especially during or shortly after their studies. According to Prospects.ac.uk, generating income and managing budgets are also key responsibilities from early on.

In these early stages, the focus is on learning practical skills, understanding the day-to-day operations of heritage organizations, and building a professional network. Developing a strong work ethic, attention to detail, and good communication skills are crucial. Being open to diverse tasks and showing initiative can lead to more responsibilities and opportunities for growth. It's also a time to explore different facets of the heritage sector to identify areas of particular interest for future specialization.

While a bachelor's degree is often a minimum requirement, some entry-level roles, particularly in CRM or technical fields, might require specific certifications or field school experience. Online courses can supplement formal education by providing specific skills or knowledge in areas like collections management or introductory GIS.

These courses can provide foundational knowledge useful for entry-level positions.

Mid-Career Positions and Specialization

With a few years of experience and often a master's degree, Cultural Heritage Managers can move into mid-career positions with more responsibility and specialization. Roles at this level might include Conservation Officer, Museum Curator, Heritage Consultant, Site Manager, or Project Archaeologist. These positions typically involve managing specific projects or areas of work, supervising junior staff or volunteers, and contributing to strategic planning.

Specialization becomes more common at this stage. A manager might focus on a particular type of heritage (e.g., maritime archaeology, industrial heritage, intangible cultural heritage), a specific skill set (e.g., digital heritage, collections care, community engagement), or a particular geographical region. Continuous professional development is important, which might involve attending workshops, conferences, or pursuing advanced certifications to deepen expertise in a chosen area.

Strong project management, communication, and problem-solving skills are essential for success in mid-career roles. The ability to write reports, manage budgets, and liaise effectively with diverse stakeholders also becomes increasingly important. Salary expectations at this level can vary widely based on the type of organization, location, and level of responsibility. For example, a mid-level fundraiser in the US cultural heritage sector might earn around $64,241.

These courses delve into specialized areas relevant to mid-career professionals.

Consider these books for advanced perspectives on museum and heritage management.

Senior Leadership and Strategic Roles

With significant experience, a proven track record, and often advanced qualifications (such as a PhD or specialized master's degree), Cultural Heritage Managers can progress to senior leadership and strategic roles. These positions might include Museum Director, Head of Conservation, Heritage Director for a national agency, or Principal Investigator/Senior Consultant in a CRM firm. At this level, responsibilities shift towards strategic oversight, policy development, high-level fundraising, advocacy, and representing the organization at national or international forums.

Senior leaders are responsible for setting the vision and direction for heritage initiatives, managing substantial budgets and large teams, and navigating complex political and economic landscapes. They play a key role in shaping heritage policy, fostering partnerships, and ensuring the long-term sustainability of heritage organizations and resources. Strong leadership, strategic thinking, financial acumen, and exceptional communication and negotiation skills are paramount.

The path to senior leadership often involves a deep commitment to the field, a continuous pursuit of knowledge and skills, and a demonstrated ability to lead and inspire others. Networking and mentorship also play a significant role in career advancement at this level. Salaries for senior leadership positions can be substantial but vary greatly depending on the size and prestige of the institution and the scope of responsibilities. A senior-level fundraiser in the US, for instance, might earn around $107,378.

This topic reflects the broader strategic thinking involved in senior roles.

Alternative Career Paths and Transitions

The skills and knowledge gained as a Cultural Heritage Manager are transferable to a variety of alternative career paths. Some professionals may transition into academia, teaching and conducting research in heritage studies, archaeology, museum studies, or related fields. Others might leverage their expertise in tourism, working as cultural tourism development officers, designing heritage tours, or managing heritage tourism destinations.

Consultancy is another common path, with experienced managers offering their services to heritage organizations, government agencies, or private developers on a project basis. Skills in research, planning, and project management are also valuable in fields like urban planning, public history, arts administration, and archival management. Some may find roles in policy development, working for government bodies or NGOs to shape heritage legislation and strategy.

For those considering a career change into cultural heritage management, many skills from other professions are transferable. Experience in project management, team leadership, communication, research, and critical thinking can all be highly relevant. Further education, such as a specialized master's degree or certificate program, can help bridge any knowledge gaps and facilitate a successful transition into this rewarding field.

These related careers may appeal to those with a background or interest in cultural heritage.

Ethical Challenges at the Forefront of Cultural Heritage Management

Cultural Heritage Management is not merely a technical or logistical endeavor; it is deeply enmeshed in complex ethical considerations. Professionals in this field regularly confront dilemmas that require careful thought, sensitivity, and a commitment to responsible stewardship. These challenges often arise from competing values, historical injustices, and the evolving understanding of what heritage means and to whom it belongs.

Navigating these ethical quandaries is a critical aspect of the profession, shaping how heritage is preserved, interpreted, and shared. An understanding of ethical frameworks and a willingness to engage in ongoing dialogue are essential for responsible practice. For those exploring this field, resources like OpenCourser's Learner's Guide can provide insights into developing critical thinking skills applicable to such complex issues.

The Ongoing Debate Over Repatriation

One of the most prominent and often contentious ethical challenges in cultural heritage management is the issue of repatriation. This refers to the return of cultural artifacts, human remains, and other heritage items to their countries or communities of origin. Many significant cultural objects are housed in museums and collections far from where they were created or discovered, often as a legacy of colonialism, conflict, or past archaeological practices that did not prioritize local ownership or consent.

The debate over repatriation involves complex legal, ethical, and emotional dimensions. Proponents argue for the inherent right of communities to their own heritage, emphasizing the cultural, spiritual, and historical significance of these items to their identity and a sense of justice for past wrongs. Opponents may raise concerns about the preservation capabilities of originating institutions, the "universal value" of certain collections, or the legal complexities of transferring ownership. Cultural Heritage Managers are often at the center of these discussions, tasked with researching provenance, engaging in dialogue with claimant communities, and navigating the policies of their institutions and governments.

This issue requires a deep understanding of historical contexts, international conventions, and the perspectives of all stakeholders involved. It highlights the need for transparency, respect, and a commitment to finding equitable solutions.

These courses explore cultures whose heritage is often part of repatriation discussions.

This book touches on the global movement and interpretation of cultural items.

Impacts of Climate Change on Heritage Sites

Climate change poses a profound and growing threat to cultural heritage worldwide. Rising sea levels, extreme weather events (such as floods, storms, and droughts), increased temperatures, and changes in environmental conditions are damaging and destroying irreplaceable archaeological sites, historic buildings, cultural landscapes, and even intangible heritage practices that depend on specific environments. Coastal heritage sites are particularly vulnerable to erosion and inundation, while changing climate patterns can accelerate the decay of organic materials and damage delicate structures.

Cultural Heritage Managers face the ethical challenge of how to respond to these unprecedented threats. This involves assessing vulnerabilities, developing adaptation and mitigation strategies, and making difficult decisions about what can be saved and what may be lost. Ethical questions arise regarding the allocation of limited resources: which sites should be prioritized for protection? How can communities whose heritage is at risk be involved in decision-making? What are the responsibilities of nations that have contributed most to climate change towards protecting global heritage?

Addressing the climate crisis in the heritage sector requires a multidisciplinary approach, integrating scientific research, traditional knowledge, innovative conservation techniques, and international cooperation. It also necessitates a shift in thinking, moving beyond traditional preservation approaches to consider strategies like managed retreat, documentation of at-risk sites before they disappear, and fostering community resilience.

Preservation Challenges in Conflict Zones

Armed conflict and political instability represent severe threats to cultural heritage. Deliberate targeting of cultural sites, looting, collateral damage from fighting, and the breakdown of governance and security can lead to devastating losses of heritage. The 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict provides an international legal framework, but its implementation remains a significant challenge.

Cultural Heritage Managers working in or concerning conflict zones face immense ethical and practical difficulties. How can heritage be protected when human lives are at immediate risk? What are the ethical considerations of intervening in a conflict situation? How can looted artifacts be recovered and repatriated? How can communities be supported in safeguarding their heritage during and after conflict?

Efforts in this area often involve risk assessment, emergency documentation, providing support and training to local heritage professionals, and collaborating with international organizations, military forces (where appropriate and ethical), and law enforcement agencies. Post-conflict recovery also presents challenges, including the ethical considerations of reconstruction, the role of heritage in peace-building and reconciliation, and addressing the trauma associated with heritage destruction.

This course touches on a region with a rich and often contested heritage.

This book directly addresses the intersection of conflict and heritage.

Acknowledging and Integrating Indigenous Rights

A critical ethical imperative in contemporary cultural heritage management is the acknowledgment and integration of indigenous rights. Historically, indigenous peoples' heritage has often been managed, interpreted, and controlled by non-indigenous institutions and individuals, frequently without their consent or benefit. This has led to the alienation of communities from their own cultural patrimony and the misrepresentation or silencing of indigenous perspectives.

Modern ethical practice demands a shift towards collaborative and rights-based approaches. This means recognizing indigenous peoples as the primary stewards and interpreters of their own heritage, respecting their traditional knowledge systems, and ensuring their free, prior, and informed consent in all matters relating to their cultural resources. It involves working in partnership with indigenous communities on issues such as site management, artifact care, repatriation, and the interpretation of their heritage.

This approach requires humility, a willingness to learn from indigenous perspectives, and a commitment to decolonizing heritage practices. It involves building long-term, respectful relationships and supporting indigenous self-determination in cultural heritage matters. Many heritage organizations and professionals are now actively working to develop more equitable and collaborative models for engaging with indigenous communities.

These courses and topics highlight the importance of understanding specific cultural contexts, including those of indigenous communities.

Global Opportunities and Prevailing Market Trends

The field of cultural heritage management operates within a global context, influenced by international collaborations, economic trends, and evolving societal values. For those considering a career in this domain, understanding the international landscape and current market dynamics can provide valuable insights into potential opportunities and challenges. The sector is dynamic, with growing recognition of heritage's role in sustainable development and cultural diplomacy.

The UK's heritage sector, for example, contributed an estimated £15.4 billion to the UK's GDP in 2021 and grew by 22.1% between 2020 and 2021. Across the EU in 2023, 7.8 million people were employed in cultural sectors, representing 3.8% of total employment. While competitive, the field shows resilience and an ongoing need for skilled professionals.

The UNESCO World Heritage Sites Network

The UNESCO World Heritage List represents one of the most significant international frameworks for cultural and natural heritage protection. Sites inscribed on this list are recognized for their "outstanding universal value," and their safeguarding is considered a responsibility of the global community. The World Heritage network creates numerous opportunities for cultural heritage managers, from working directly on the management and conservation of these prestigious sites to engaging in international policy development and capacity-building initiatives.

Employment related to World Heritage sites can be found within national heritage agencies, site management authorities, international NGOs, and UNESCO itself. These roles often require expertise in areas such as nomination dossier preparation, monitoring and reporting, conservation planning, and stakeholder engagement, often in multicultural and international contexts. The rigorous standards and international collaboration involved in World Heritage work can provide unique professional development experiences.

Understanding the principles of the World Heritage Convention and the operational guidelines for its implementation is crucial for those aspiring to work in this sphere. Many specialized master's programs in heritage management include modules specifically focused on UNESCO and World Heritage.

This course, while not directly about UNESCO, deals with heritage of significant global interest.

Emerging Markets in Heritage Tourism

Heritage tourism, where people travel to experience cultural and historical sites, is a significant and growing segment of the global tourism industry. While established heritage destinations in Europe and North America continue to attract visitors, there is increasing interest in emerging markets in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and Eastern Europe, which boast rich and diverse cultural landscapes. This growth presents both opportunities and challenges for cultural heritage managers.

The opportunities lie in the potential for heritage tourism to generate revenue for conservation, create local employment, and foster cultural pride. Managers can be involved in developing sustainable tourism strategies, creating engaging visitor experiences, and ensuring that tourism benefits local communities. However, the challenges include managing visitor numbers to prevent overcrowding and site degradation, ensuring that tourism development is culturally sensitive and equitable, and preventing the "commodification" of heritage where its authentic meaning is lost.

Skills in sustainable tourism planning, community-based tourism development, marketing, and visitor management are increasingly valuable in this context. Cultural sensitivity and an understanding of the socio-economic impacts of tourism are also essential. According to OECD reports on tourism, a strategic approach is needed to maximize benefits while minimizing negative impacts.

These courses cover diverse cultural regions, some of which are prominent in heritage tourism.

Employment Across Public and Private Sectors

Employment opportunities for Cultural Heritage Managers exist across both the public and private sectors, as well as in non-profit organizations. The public sector has traditionally been a major employer, with roles in national heritage agencies (like Historic England or the National Park Service in the US), local government planning departments, publicly funded museums, and archaeological services. These roles often focus on regulatory compliance, policy implementation, and the management of public heritage assets.

The private sector offers opportunities in areas like cultural resource management (CRM) consulting, where firms are hired to conduct heritage impact assessments for development projects. There are also roles in private museums, historic house management, auction houses, and heritage tourism enterprises. The non-profit sector, including trusts, foundations, and community-based heritage organizations, also plays a vital role, often focusing on advocacy, conservation projects, and public engagement. The European Labour Authority notes that in some EU member states, the cultural and creative sector is primarily public, while private activities are less accounted for in formal statistics.

The balance between public and private sector employment can vary by country and region. However, the ability to work effectively with stakeholders from all sectors is increasingly important, as many heritage projects involve public-private partnerships or collaborations between government, commercial, and community interests.

Post-Pandemic Recovery and Digital Adaptation Trends

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on the cultural heritage sector, with widespread closures of sites and museums, disruptions to tourism, and funding challenges. However, the sector has shown resilience, and the post-pandemic period has seen a focus on recovery and adaptation. One of the most significant trends accelerated by the pandemic is the increased emphasis on digital engagement.

With physical access restricted, many heritage institutions rapidly expanded their online presence, offering virtual tours, digital collections, online educational programs, and social media engagement. This trend towards digital adaptation is likely to continue, creating demand for professionals with skills in digital content creation, online curation, virtual programming, and digital marketing. The IAEA highlights the role of technology in preservation, noting continuous updates and expertise are needed.

The pandemic also highlighted the importance of local audiences and community engagement, as international tourism was curtailed. There is a renewed focus on making heritage relevant and accessible to local communities and on developing more sustainable and resilient operating models. Furthermore, issues of social equity and inclusion in heritage have gained greater prominence, prompting organizations to re-examine their collections, narratives, and engagement strategies. According to the UNESCO World Heritage Centre, adapting to global challenges like pandemics requires innovative and community-focused approaches.

These courses reflect the increasing importance of digital skills in the heritage sector.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Aspiring Cultural Heritage Managers

Embarking on a career in cultural heritage management can raise many questions. This section aims to address some common queries, offering insights to help you navigate your path with greater clarity. Remember, the journey is unique for everyone, but understanding these aspects can provide a helpful foundation.

Is field experience more valuable than advanced degrees in this field?

This is a common question, and the answer is often: both are highly valuable and, in many cases, complementary. Advanced degrees, such as a master's in heritage management, museum studies, or conservation, provide essential theoretical knowledge, research skills, and specialized understanding of heritage principles, ethics, and methodologies. They can open doors to more specialized roles and higher levels of responsibility.

However, field experience – gained through internships, volunteer work, field schools, or entry-level positions – is crucial for developing practical skills, understanding real-world challenges, and building a professional network. Many employers look for candidates who have both a solid academic foundation and demonstrated practical abilities. For some roles, particularly those involving hands-on conservation or archaeological fieldwork, extensive practical experience and specific technical training are indispensable.

Ultimately, the ideal balance can depend on your specific career goals within the diverse field of cultural heritage management. Some individuals pursue advanced degrees after gaining some initial field experience, while others integrate practical components like internships directly into their academic programs. The key is to seek opportunities to build both your knowledge base and your practical competence. Many job descriptions, like one from the National Capital Authority in Australia, explicitly require tertiary qualifications and relevant work experience.

How competitive are international positions in cultural heritage?

International positions in cultural heritage management can be quite competitive. These roles, whether with international organizations like UNESCO, multinational NGOs, or in foreign countries, often attract a global pool of highly qualified applicants. Factors contributing to this competitiveness include the prestige associated with international work, the opportunity to engage with diverse cultures and heritage sites, and sometimes, limited numbers of such positions.

To be a strong candidate for international roles, a combination of factors is usually necessary. Advanced academic qualifications, specialized expertise in a relevant area (such as World Heritage management, intangible heritage, or a specific conservation field), and significant professional experience are often prerequisites. Language skills are frequently essential, with proficiency in English widely expected and knowledge of other languages (relevant to the region or organization) being a significant asset. Demonstrating cross-cultural competence, adaptability, and experience working in diverse international teams is also highly valued.

Networking within international heritage circles, attending international conferences, and gaining experience on projects with an international dimension can improve visibility and opportunities. While challenging, securing an international position can offer unparalleled experiences and career development. Research from the CHARTER project indicates that about 10% of vacancies they analyzed were from international organizations, suggesting a notable, albeit specialized, segment of the job market.

What languages are most beneficial for a career in cultural heritage management?

Proficiency in English is widely considered essential in the international cultural heritage field, as it is often the lingua franca for conferences, publications, and collaborative projects. Beyond English, the most beneficial languages depend heavily on your geographical area of interest and specialization. If you aim to work in Latin America, Spanish and Portuguese are crucial. For European heritage, French, German, Italian, and Spanish can be very advantageous, given the rich heritage and numerous institutions in these regions.

For those specializing in particular cultures or archaeological areas, knowledge of the local languages is often indispensable for research, community engagement, and understanding primary sources. For example, working with Middle Eastern heritage might benefit from Arabic, Turkish, or Farsi; East Asian heritage from Chinese, Japanese, or Korean; and so on. Understanding indigenous languages can be profoundly important when working with indigenous heritage.

Even if not aiming for complete fluency, a working knowledge of relevant languages can significantly enhance your ability to collaborate, conduct research, and engage meaningfully with local communities and heritage contexts. Language skills demonstrate cultural sensitivity and a deeper commitment to understanding the heritage you work with. Online language learning platforms, accessible through resources like OpenCourser's Languages section, can be a great way to begin or enhance your language studies.

These courses offer introductions to languages connected to rich cultural heritages.

Can I transition from a museum curator role to cultural heritage management?

Yes, transitioning from a museum curator role to broader cultural heritage management is a viable and often logical career progression. Museum curators already possess many skills and knowledge areas that are directly transferable and highly valued in the wider heritage field. These include expertise in collections management, research, interpretation, exhibition development, and often, public engagement.

The scope of cultural heritage management extends beyond museum walls to include historic sites, cultural landscapes, intangible heritage, and heritage policy. A curator wishing to transition might seek to broaden their experience in areas such as site management, conservation planning for built heritage, community-based heritage projects, stakeholder engagement with diverse groups (including government agencies or developers), or heritage policy and advocacy.

Further education or professional development in these broader areas might be beneficial. For example, a master's degree or certificate in Cultural Heritage Management or Cultural Resource Management could provide the necessary framework and credentials. Highlighting transferable skills such as project management, budgeting, fundraising (if applicable), and communication in applications and interviews will be key. The experience of preserving and interpreting cultural assets within a museum context provides a strong foundation for the stewardship of heritage in its diverse forms.

How is Artificial Intelligence (AI) impacting conservation and heritage practices?

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is beginning to make its mark on cultural heritage management, offering new tools and approaches for conservation, research, and engagement. While still an emerging area, the potential impacts are significant. AI algorithms can be used to analyze vast datasets, such as high-resolution imagery of artifacts or sites, to detect subtle changes or patterns of deterioration that might be invisible to the human eye. This can aid in early diagnosis of conservation issues and more targeted interventions.

In research, AI can assist in tasks like deciphering ancient texts, classifying archaeological finds, or reconstructing fragmented objects or frescoes from digital scans. For public engagement, AI-powered chatbots can provide information to museum visitors, and machine learning can help personalize digital heritage experiences. There is also potential for AI in managing digital archives and making large collections more searchable and accessible.

However, the use of AI also raises ethical questions regarding data bias, the authenticity of AI-generated reconstructions, and the potential displacement of human expertise. Cultural heritage managers will need to critically assess how AI can be responsibly integrated into their practices, focusing on how it can augment human skills rather than replace them. As AI tools become more sophisticated and accessible, professionals in the field will benefit from understanding their capabilities and limitations.

What are typical project timelines for heritage preservation initiatives?

Project timelines in heritage preservation can vary dramatically depending on the scale, complexity, and nature of the initiative. A small-scale conservation treatment for a single artifact might take days or weeks. In contrast, a major restoration project for a historic building or the development of a comprehensive management plan for a large archaeological park could span several years, or even decades.

Factors influencing timelines include the extent of research and documentation required, the complexity of conservation interventions, the need for stakeholder consultation and community engagement, securing funding, obtaining necessary permits and approvals, and the availability of specialized expertise and materials. For example, an archaeological excavation project will have distinct phases: survey and site identification, excavation, finds processing and analysis, and finally, report writing and dissemination, each with its own timeline.

Large-scale projects often involve multiple phases, from initial feasibility studies and planning, through implementation, to ongoing monitoring and maintenance. Effective project management skills, including realistic scheduling, budget management, and risk assessment, are therefore crucial for Cultural Heritage Managers to ensure that preservation initiatives are completed successfully and sustainably.

Embarking on Your Journey in Cultural Heritage Management

A career as a Cultural Heritage Manager is a commitment to safeguarding the diverse expressions of human history and creativity. It's a path that demands dedication, a blend of scholarly knowledge and practical skills, and a deep respect for the cultures and communities whose heritage you will work to protect and promote. While challenging, the rewards are immense, offering the chance to make a tangible difference in preserving our collective past for future generations.

If this field resonates with your aspirations, we encourage you to continue exploring. Utilize resources like OpenCourser to discover relevant courses and programs, delve into the suggested readings, and learn about the experiences of those already in the field. Whether you are just starting your educational journey, considering a career pivot, or seeking to advance your existing skills, there are pathways available to help you achieve your goals. The world's heritage is vast and varied, and dedicated professionals are always needed to ensure its enduring legacy.