Archivist

Archivist: Guardians of Memory

Archivists are the professionals entrusted with the critical task of appraising, collecting, organizing, preserving, and providing access to records and archives deemed to have long-term value. These records can take many forms, from ancient manuscripts and government documents to digital files and audiovisual materials. In essence, archivists ensure that the evidence of the past is available to inform the present and future, serving as guardians of cultural, institutional, corporate, and personal memory.

Working as an archivist involves a unique blend of historical knowledge, meticulous organizational skills, and increasingly, technological expertise. It's a field that offers the satisfaction of connecting people with history, whether it's helping a scholar uncover a forgotten narrative, assisting a family in tracing their genealogy, or enabling an organization to understand its own evolution. The role demands careful judgment, ethical considerations, and a passion for preserving the authentic voices and records of times gone by.

Introduction to Archivists

What is an Archivist?

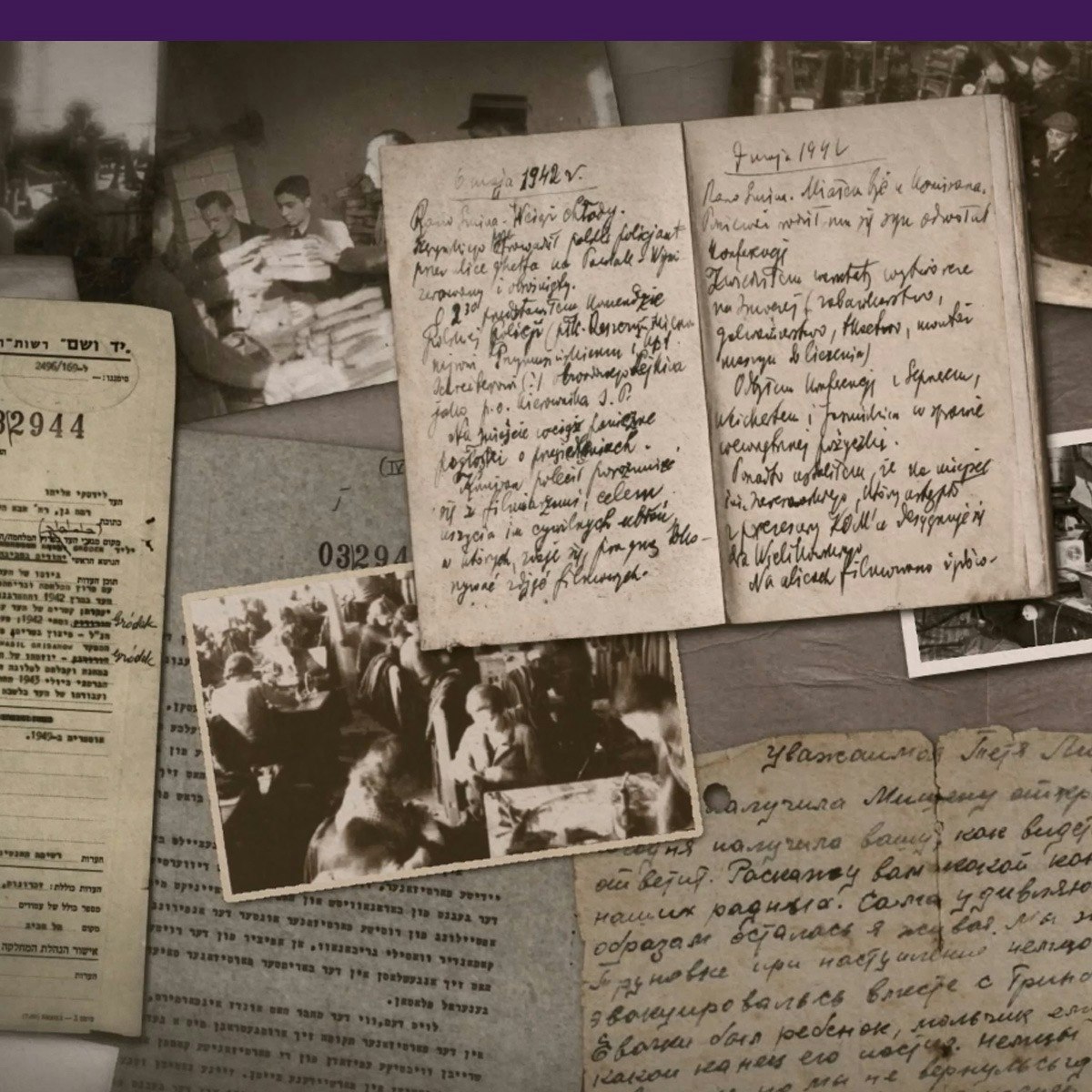

At its core, an archivist identifies, saves, and makes available records that document human activity. They work with unique, original materials that provide firsthand evidence of historical events, societal trends, and individual lives. Unlike librarians, who primarily deal with published materials like books and journals, archivists handle unpublished records – letters, diaries, photographs, meeting minutes, digital data, sound recordings, and much more.

The primary role involves selecting which records hold enduring value (a process called appraisal), arranging and describing these records according to established principles (like provenance and original order), ensuring their long-term preservation against physical decay or technological obsolescence, and facilitating access for researchers and the public while navigating privacy and ethical considerations.

Archivists are essential for accountability, memory, and understanding. They ensure that evidence of actions and decisions is preserved, that cultural heritage is maintained, and that future generations can learn from the experiences of the past. Their work underpins historical research, legal evidence, cultural identity, and institutional memory.

A Brief History of Archival Work

The practice of keeping records dates back to ancient civilizations, where clay tablets documented economic transactions and stone inscriptions recorded royal decrees. These early forms of archives served administrative, legal, and commemorative purposes. In ancient Rome and Greece, formal archives held state documents, laws, and treaties, recognizing the importance of organized record-keeping for governance.

During the medieval period, monasteries and royal courts became key repositories, preserving religious texts, legal documents, and chronicles. The concept of archives as distinct collections, managed for preservation and access, began to solidify. The French Revolution marked a turning point, establishing the idea of national archives accessible to the public, reflecting a shift towards democratic accountability and historical consciousness.

The 20th century saw the professionalization of archival work, with the development of standardized theories, principles, and practices, often spurred by the need to manage vast amounts of government records generated during world wars. The digital revolution presented new challenges and opportunities, leading to the fields of digital archiving and preservation, which continue to evolve rapidly today.

Understanding this historical context helps illuminate the enduring principles and evolving methods of archival practice. To delve deeper into the past and its preservation, exploring history through online resources can be highly beneficial.

Explore History Courses on OpenCourser

Why Archives Matter

Archives are fundamental to understanding who we are, where we come from, and how society functions. They preserve the memory of nations, communities, organizations, and individuals. Without archives, reconstructing the past accurately would be impossible, leaving us adrift without historical context or evidence.

For institutions and corporations, archives provide vital operational memory, informing decisions, ensuring compliance, and documenting achievements and failures. For individuals and communities, they offer links to identity, heritage, and family history, often holding deep personal significance. Cultural heritage institutions rely on archives to preserve artistic, literary, and historical artifacts for future generations.

In a world saturated with information, archives provide authentic, primary sources that counter misinformation and offer verifiable evidence. They are crucial for democratic accountability, enabling citizens to scrutinize government actions and hold power accountable. Preserving this memory, in all its diverse forms, is the vital contribution of the archivist.

Exploring cultural heritage through primary sources is a rewarding experience. These courses offer insights into specific historical periods and cultural artifacts.

Overview of Archival Work

Types of Archivists and Their Settings

The archival field is diverse, with professionals working in various settings, each with unique collections and user bases. Government archivists manage records at local, state, or national levels, dealing with official documents, legislative records, and materials related to public administration. Their work is crucial for transparency and governmental accountability.

Academic archivists work in colleges and universities, preserving institutional records (like administrative files, student publications, and faculty papers) as well as special collections of manuscripts, rare books, and historical documents relevant to the institution's research interests. They support teaching, learning, and scholarly research.

Corporate archivists manage the historical records of businesses, preserving documents related to company history, product development, marketing campaigns, and executive decisions. These archives support branding, legal needs, and corporate memory. Other types include museum archivists (handling records related to artifacts and museum operations), religious archivists, community archivists (preserving the history of specific communities, often underrepresented groups), and digital archivists specializing in electronic records.

These diverse settings reflect the wide applicability of archival skills in preserving memory across different sectors of society.

Key Industries Employing Archivists

Archivists find employment across a spectrum of industries where the long-term preservation and management of records are valued. Government agencies at all levels (federal, state, local) are major employers, housing vast collections of public records. Educational institutions, particularly universities and colleges with libraries and special collections, frequently hire archivists.

Museums, historical societies, and other cultural heritage organizations employ archivists to manage their institutional records and collections of historical materials. Corporations, especially those with long histories or in heavily regulated industries, maintain corporate archives. Religious organizations often have archives documenting their history and activities.

Non-profit organizations, professional associations, and even private families or individuals with significant collections may also employ archivists. The rise of digital information has also created demand in sectors dealing with large-scale data management and digital preservation, sometimes overlapping with roles in information governance or data management.

A Day in the Life

The daily tasks of an archivist can vary significantly depending on the size and type of institution, the nature of the collections, and the archivist's specific role (e.g., processing archivist, digital archivist, reference archivist). However, some common activities thread through the profession.

A typical day might involve processing newly acquired collections: arranging materials logically, creating descriptive finding aids (inventories or guides to the collection), and housing items in appropriate archival containers. Another part of the day could be spent on preservation tasks, such as monitoring environmental conditions, digitizing fragile materials, or managing digital storage systems.

Reference work is often a key component, involving responding to inquiries from researchers via email, phone, or in person, retrieving materials, and providing guidance on using the collections. Outreach activities, like giving presentations, curating exhibits, or developing web content, might also feature. Collaboration with donors, other staff members, and IT professionals is common. While some tasks are routine, the variety of materials and research questions often makes the work engaging and intellectually stimulating.

Core Responsibilities of an Archivist

Acquisition and Appraisal

A fundamental responsibility of archivists is deciding what materials should become part of the archive. Acquisition involves actively seeking out or receiving donations of records that align with the institution's collecting policy. This might involve contacting potential donors, negotiating terms of donation, and legally transferring ownership.

Appraisal is the critical process of evaluating records to determine their long-term historical, administrative, legal, or research value. Not everything can or should be saved. Archivists use established criteria and their subject expertise to assess factors like the records' uniqueness, authenticity, informational content, potential research use, and relationship to other holdings.

This selection process is crucial for building meaningful and manageable collections. It requires careful judgment, understanding of historical context, and often, difficult decisions about what aspects of the past will be preserved for the future. Ethical considerations, such as representing diverse perspectives, also play a role in modern appraisal.

These courses delve into historical interpretation and the use of primary sources, skills vital for appraisal.

Preservation and Conservation

Once records are acquired, ensuring their long-term survival is paramount. Preservation involves creating a stable environment to slow deterioration, including controlling temperature, humidity, and light levels, and using acid-free folders and boxes. It also includes disaster planning and security measures.

Conservation refers to the physical treatment of damaged items to stabilize them or repair harm. This is often performed by specialized conservators who might mend torn paper, treat mold, or restore faded photographs. Archivists typically handle basic preservation tasks and collaborate with conservators for more complex treatments.

Digital preservation presents unique challenges. It involves strategies for migrating data to new formats as technology changes, ensuring the integrity and authenticity of digital files over time, managing metadata, and safeguarding against data loss or corruption. This requires ongoing attention and technological expertise.

Handling historical documents requires care. These books offer insights into managing and preserving collections.

Arrangement, Description, and Access

To make archives usable, archivists arrange and describe them. Arrangement involves organizing records according to archival principles, primarily respecting provenance (keeping records created by one entity together) and original order (maintaining the order established by the creator, if possible). This context is crucial for understanding the records.

Description involves creating finding aids – tools like inventories, guides, or catalogs that detail the content, context, and structure of a collection. These finding aids help researchers identify relevant materials. Standardized descriptive practices, such as using metadata schemas like EAD (Encoded Archival Description) or DACS (Describing Archives: A Content Standard), ensure consistency and facilitate online discovery.

Providing access is the ultimate goal. This includes assisting researchers in reading rooms, fulfilling remote requests, and making digital surrogates available online. Archivists must balance the need for access with responsibilities to protect fragile materials, respect donor restrictions, and safeguard privacy, especially in records containing sensitive personal information.

Understanding how information is structured and made accessible is key. These resources touch on information literacy and management.

Collaboration and Outreach

Archivists rarely work in isolation. They collaborate extensively with donors, researchers, colleagues within their institution (librarians, curators, IT specialists), and professionals at other archives. Building relationships with donors is vital for acquiring new collections, while assisting researchers effectively is central to the archive's mission.

Collaboration within the institution ensures smooth operations, such as coordinating digital preservation efforts with IT departments or planning joint exhibitions with curators. Sharing knowledge and resources with other archival institutions through professional networks enhances practice across the field.

Outreach involves promoting the archives and engaging the public. This can include creating exhibits (physical or online), giving presentations, writing blog posts or articles, working with educators to incorporate archival materials into curricula, and using social media to highlight collections. Effective outreach raises awareness of the archive's value and encourages broader use of its resources.

Engaging with communities and educators requires specific skills. These courses explore community engagement and teaching with museum resources.

Formal Education Pathways

Undergraduate Foundations

While a specific undergraduate degree is not typically required to become an archivist, certain majors provide a strong foundation. Degrees in History are very common, as they develop critical thinking, research skills, and an understanding of historical context necessary for appraisal and description.

Library Science programs, though often focused on published materials, can introduce foundational concepts of information organization, cataloging, and preservation relevant to archival work. Other helpful majors include Anthropology, Classics, Political Science, English, or any field involving rigorous research and analysis of primary sources.

Regardless of major, coursework emphasizing research methods, writing, critical analysis, and potentially a foreign language can be beneficial. Gaining practical experience through internships or volunteer work in an archive or special collection during undergraduate studies is highly recommended and often crucial for admission into graduate programs.

Understanding history is fundamental. Courses exploring different historical periods can broaden perspective.

Graduate Studies in Archival Science

The standard professional qualification for archivists in North America is a Master's degree. Common degrees include a Master of Library Science (MLS) or Master of Library and Information Science (MLIS) with a specialization or concentration in archives management. Some universities offer dedicated Master of Archival Studies (MAS) degrees.

These graduate programs provide specialized training in archival theory and practice, covering topics such as appraisal, arrangement and description, preservation (physical and digital), reference services, ethics, legal issues, and management of archival programs. Coursework often includes hands-on experience through practicums or internships.

Some programs offer dual degrees, combining archival studies with fields like History (MA/MLS) or Public History, which can be advantageous for certain career paths. Choosing a program accredited by relevant professional bodies (like the American Library Association or potentially aligned with Society of American Archivists guidelines) is generally advised.

Certifications and Advanced Studies

Beyond the Master's degree, archivists can pursue certifications to demonstrate specialized knowledge and commitment to the profession. The Academy of Certified Archivists (ACA) offers the Certified Archivist (CA) credential, obtained by passing an exam covering core archival knowledge areas. While not always required for employment, certification can enhance career prospects.

Specialized certifications, such as the Digital Archives Specialist (DAS) certificate offered by the Society of American Archivists (SAA), cater to the growing need for expertise in managing electronic records. These often involve completing a series of specific courses and assessments.

For those interested in research, teaching, or high-level leadership roles, a Ph.D. in Archival Studies, Information Science, or a related historical field may be pursued. Doctoral studies involve advanced coursework, original research, and the completion of a dissertation, contributing new knowledge to the field.

These books provide insight into the practical and theoretical aspects of museum and information management.

Online Learning and Skill Development

Can You Learn Archival Skills Online?

While a formal Master's degree is the standard entry point, online learning offers valuable pathways for building foundational knowledge and specific skills relevant to archival work. Online courses can be particularly useful for those exploring the field, career changers seeking to bridge skill gaps, or current professionals needing to update their expertise, especially in rapidly evolving areas like digital preservation.

Foundational concepts such as archival theory, principles of arrangement and description, basic preservation techniques, and information literacy can often be introduced effectively through online modules, readings, and lectures. Many universities offer components of their archival programs online, and professional organizations provide webinars and workshops.

However, hands-on experience with physical materials and direct mentorship remain crucial aspects of archival training that are harder to replicate entirely online. Therefore, online learning is often best viewed as a supplement to, or preparation for, practical experience gained through internships, volunteer work, or entry-level positions.

OpenCourser offers a wide range of courses covering History, Humanities, and Information Security, which touch upon skills relevant to archivists.

Priority Topics for Online Study

For individuals leveraging online resources, certain topics are particularly well-suited for this format and highly relevant to modern archival practice. Digital preservation is a prime example; understanding concepts like file formats, metadata, digital storage, integrity checks, and emulation can be effectively learned online.

Metadata standards and practices (like Dublin Core, MODS, PREMIS) are crucial for describing and managing both physical and digital assets, and online courses can provide detailed instruction. Introduction to database management and information organization principles are also valuable and readily available online.

Courses covering information literacy, research methods, copyright and intellectual property basics, and project management offer transferable skills applicable to archival settings. Learning about specific technologies like content management systems (CMS), digital asset management (DAM) systems, or digitization tools can also be pursued online.

These online courses cover relevant areas like digital humanities, database fundamentals, and information literacy, providing valuable skills for aspiring or practicing archivists.

Building a Portfolio with Independent Projects

Supplementing online coursework with practical projects is essential, especially for those without formal archival experience. Creating a portfolio demonstrates initiative and tangible skills to potential employers or graduate programs. Independent projects can simulate real-world archival tasks.

One possibility is volunteering for a local historical society, museum, or community archive, even if tasks start small. Documenting this experience is valuable. Alternatively, individuals can undertake personal archiving projects, such as organizing and describing a family collection of letters or photographs, applying archival principles and documenting the process.

Creating a digital collection using online platforms (like Omeka) showcases skills in digitization, metadata creation, and web presentation. Contributing to crowdsourced transcription or indexing projects for established archives (often available online) provides experience with historical documents and descriptive practices. Presenting project work through a personal website or blog can effectively showcase your skills and passion for the field.

Consider exploring courses on digital tools or presentation methods to enhance your portfolio.

Career Progression and Opportunities

Starting Your Archival Career

Entry into the archival profession typically begins after completing a Master's degree, often coupled with internship or volunteer experience. Common entry-level roles include Archival Assistant, Processing Archivist, Project Archivist, or potentially Records Analyst/Manager, particularly in corporate or government settings.

Archival Assistants often support senior archivists in various tasks, including processing, reference, and preservation activities. Processing Archivists focus specifically on arranging and describing collections. Project Archivists are usually hired on temporary contracts to work on specific grant-funded projects, often involving processing backlogs or digitization initiatives.

Records Managers focus on the lifecycle of an organization's current records, including creation, maintenance, use, and disposition, applying principles similar to archival appraisal. Gaining diverse experiences in these early roles builds a strong foundation for future specialization and advancement.

Mid-Career Specializations

With experience, archivists often develop specialized expertise. Digital Archivist is a rapidly growing specialization focused on managing born-digital materials and digitized collections, requiring strong technical skills in digital preservation, metadata, and relevant technologies.

Some archivists specialize in specific types of materials, such as audiovisual archives, photographic collections, or architectural records. Others focus on specific functions, becoming Reference Archivists who excel at assisting researchers, or Outreach Archivists dedicated to public programming and engagement.

Conservation, while often requiring separate, specialized training (sometimes at the Master's level in conservation itself), can be a path for archivists interested in the physical treatment of materials. Subject specialization (e.g., specializing in the archives of a particular historical period, scientific field, or artistic movement) is also common, particularly in academic or museum settings.

Information architecture shares some principles with archival arrangement and description.

Leadership and Management Roles

Experienced archivists can advance into leadership positions. Roles like Head Archivist, Lead Archivist, or Supervising Archivist typically involve managing teams, overseeing workflows, and handling more complex projects.

Higher-level management roles include Director of Archives, Head of Special Collections, or Director of Collections. These positions involve strategic planning, budget management, fundraising, policy development, staff supervision, and representing the archives within the larger institution or to external stakeholders.

Leadership requires not only deep archival knowledge but also strong management, communication, and advocacy skills. Progression often involves demonstrating successful project management, team leadership, and a broad understanding of the challenges and opportunities facing the institution and the archival field.

Developing management skills is crucial for leadership roles.

Browse Management Courses on OpenCourser

Essential Skills and Competencies

Technical Archival Skills

Proficiency in core archival techniques is fundamental. This includes understanding and applying principles of appraisal, arrangement, and description. Familiarity with descriptive standards like DACS and metadata schemas (EAD, Dublin Core, PREMIS) is essential for creating finding aids and managing digital objects.

Skills in preservation techniques for various formats (paper, photographic, audiovisual, digital) are crucial. This involves knowledge of proper handling, storage environments, and basic conservation treatments. Increasingly, technical skills related to digitization, including operating scanners, image editing software, and understanding file formats and quality control, are necessary.

Familiarity with archival management software (like ArchivesSpace or AtoM), digital repository systems (like DSpace or Fedora), and database management is also highly valued. Understanding information retrieval principles helps in designing effective access systems.

Database skills are increasingly important in managing archival information.

Critical Soft Skills

Beyond technical expertise, certain soft skills are vital for success as an archivist. Meticulous attention to detail is paramount for tasks like arrangement, description, and preservation, where accuracy and consistency are key. Strong organizational and time management skills are needed to handle multiple projects and large volumes of material.

Excellent research and analytical skills are necessary for appraisal, contextualizing records, and assisting researchers. Effective written and oral communication skills are crucial for creating clear finding aids, interacting with donors and researchers, writing reports, and conducting outreach.

Problem-solving abilities help address unique challenges presented by complex collections or preservation issues. Adaptability and a willingness to learn are important in a field constantly evolving with new technologies and theories. Crucially, strong ethical judgment is required when dealing with issues of access, privacy, copyright, and representation in collections.

These courses can help develop essential communication and research skills.

Adapting to Emerging Technologies

The archival field is continually influenced by technological advancements. Proficiency in digital technologies is no longer optional but core to the profession. Understanding digital preservation strategies, including format migration, emulation, and checksum verification, is critical.

Familiarity with data management principles, database structures, and potentially scripting languages (like Python) can be advantageous for managing large digital collections and automating tasks. Awareness of linked data principles and semantic web technologies may become increasingly relevant for enhancing discovery and access.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning are emerging areas with potential applications in archives, such as automated metadata generation, transcription of handwritten documents, or enhancing search capabilities. While deep AI expertise may not be required for all archivists, understanding its potential applications and limitations will be increasingly important for future practice.

Staying abreast of technological trends requires continuous learning. Exploring resources on data management and AI can be beneficial.

Explore Artificial Intelligence Courses

Challenges Facing Archivists

Complexities of Digital Preservation

Preserving digital materials presents significant hurdles. Unlike physical objects that degrade predictably, digital files face threats like file format obsolescence (software needed to read them disappears), media failure (storage devices degrade), and data corruption. Ensuring the long-term accessibility and authenticity of digital records requires proactive, ongoing management.

The sheer volume of digital information being created poses a major challenge for appraisal and storage. Determining what to keep and managing massive datasets requires sophisticated tools and strategies. Metadata creation and management are also more complex for digital objects, needing detailed technical and descriptive information to ensure future usability.

Developing and maintaining the necessary technical infrastructure and expertise for digital preservation can be costly and requires continuous investment and updating. Many institutions struggle to secure adequate resources, making long-term digital stewardship a persistent challenge across the field.

Funding and Resource Constraints

Many archival institutions, particularly those in the public sector or non-profit sphere, operate under significant funding and resource limitations. Insufficient budgets can impact staffing levels, the ability to acquire new collections, preservation efforts (especially costly digital preservation), technology upgrades, and outreach programs.

Limited staffing often means archivists must juggle multiple responsibilities, leading to backlogs in processing collections or delays in responding to research requests. Competition for grant funding is often fierce, requiring significant effort in grant writing and project management.

Advocating for the value of archives and demonstrating their impact is crucial for securing necessary funding. This often involves quantifying usage, highlighting successful research outcomes, and connecting archival work to broader institutional or community goals, yet proving tangible return on investment can be difficult.

Ethical Considerations and Dilemmas

Archivists frequently navigate complex ethical terrain. Balancing the imperative to provide access with the need to protect individual privacy, especially in collections containing sensitive personal information (e.g., medical records, personnel files), is a constant challenge governed by laws and ethical codes.

Issues of copyright and intellectual property rights affect how materials can be digitized, shared, and used. Donor-imposed restrictions on access or use must also be respected. Furthermore, archivists grapple with ensuring equitable representation in their collections, addressing historical biases that may have excluded marginalized voices, and ethically describing sensitive or potentially offensive materials.

Decisions about appraisal (what to keep and what to discard) carry ethical weight, shaping the historical record that future generations inherit. Transparency in policies and practices, and adherence to professional codes of ethics, such as that provided by the Society of American Archivists, are essential for navigating these dilemmas responsibly.

Understanding cultural contexts and ethical frameworks is vital.

Future Trends in Archival Science

Artificial Intelligence and Automation

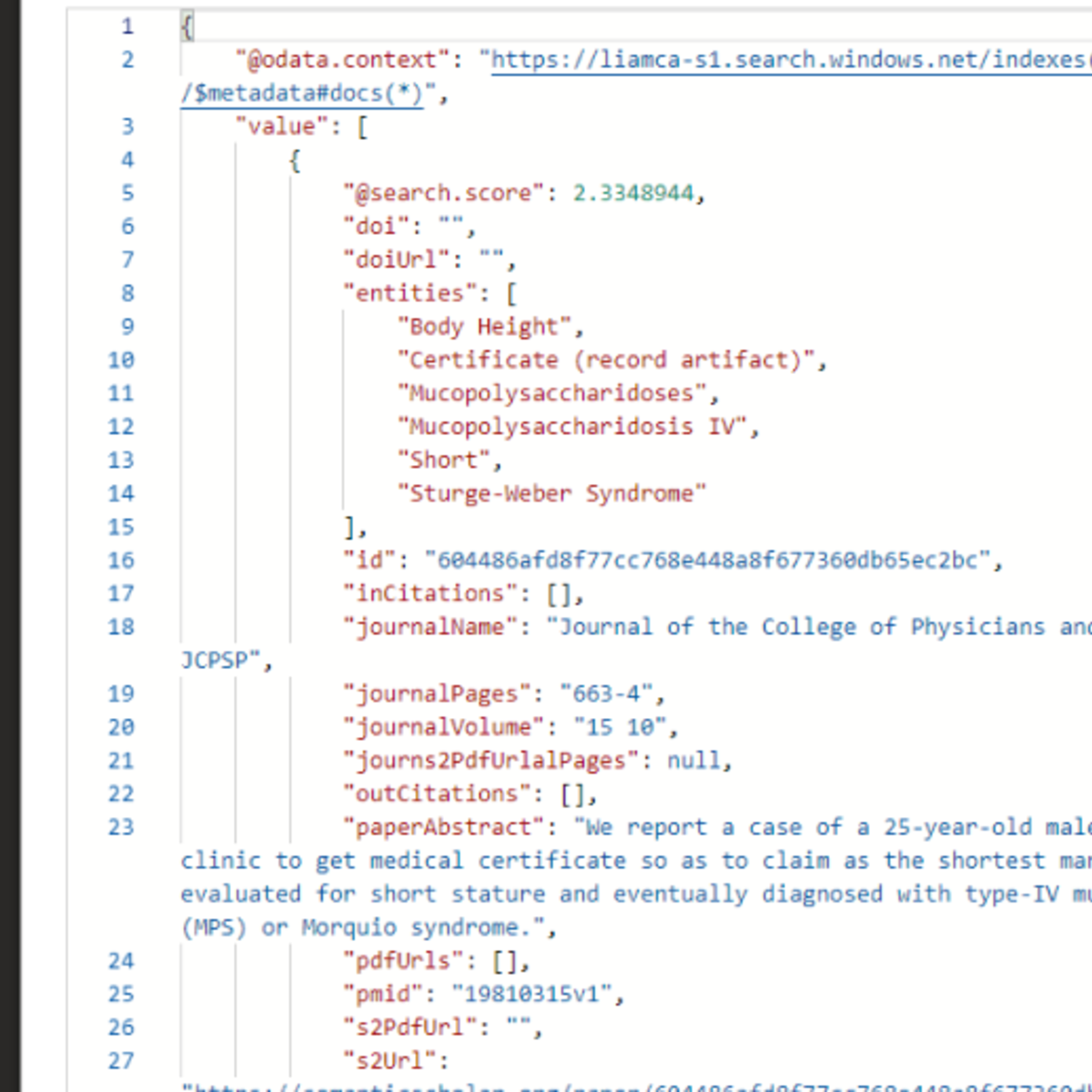

Artificial intelligence (AI) is poised to significantly impact archival workflows. AI tools show promise for automating tasks like transcribing handwritten documents, generating preliminary metadata descriptions, identifying entities (people, places, organizations) within texts, and potentially assisting with sensitivity reviews for privacy concerns.

This automation could help address processing backlogs and improve the discoverability of collections. AI-powered search algorithms might enable more sophisticated querying of archival content. However, challenges remain regarding the accuracy of AI tools, potential biases embedded in algorithms, and the need for human oversight and quality control.

Archivists will need to develop skills to evaluate, implement, and manage AI tools effectively and ethically. The focus may shift from manual description to verifying and refining AI-generated data, requiring a blend of traditional archival expertise and technological understanding.

Climate Change and Physical Collections

Climate change poses increasing risks to physical archival collections. More frequent and severe weather events, such as floods, hurricanes, and wildfires, threaten the physical safety of repositories and the materials they hold. Rising temperatures and humidity fluctuations can accelerate the deterioration of paper, photographs, and other organic materials, requiring more robust environmental controls.

Institutions need to enhance disaster preparedness plans, considering climate-specific risks in their regions. Sustainable practices within archival management, such as energy-efficient storage facilities and reduced environmental footprints, are becoming more critical considerations.

The impact of climate change also extends to the content of archives, as records documenting environmental shifts, policy responses, and community impacts become increasingly important historical resources.

Globalization and Collaboration

Archival work is becoming increasingly interconnected globally. Digital technologies facilitate international collaboration on projects like digitizing and providing access to transnational collections or developing shared descriptive standards. Researchers often need access to archives in multiple countries, requiring greater cooperation between institutions.

Issues like managing archives related to migration, colonialism, and international organizations necessitate cross-border dialogue and potentially shared stewardship models. Efforts to repatriate or provide digital access to cultural heritage held outside its community of origin also drive international collaboration.

The challenges of preserving digital information, which often exists across borders, also benefit from shared international standards and cooperative strategies. Professional organizations and collaborative projects play a key role in fostering these global connections.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the typical salary range for an archivist?

Salaries for archivists vary considerably based on factors like geographic location, type of institution (government, academic, corporate, non-profit), level of experience, education, and specific responsibilities. Entry-level positions typically offer lower salaries, while senior management roles command higher compensation.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the median annual wage for archivists, curators, and museum workers was $63,940 in May 2023. However, this figure groups several related occupations. Data specifically for archivists might show variation, with those in federal government or corporate settings potentially earning more than those in smaller non-profits or local historical societies. It's advisable to research salary ranges specific to the region and sector of interest using resources like the BLS Occupational Outlook Handbook or surveys from professional archival associations.

Remember that competition for positions can be strong, particularly in desirable locations or prestigious institutions, which can also influence salary negotiations.

What is the job outlook for archivists?

The job outlook for archivists is projected to grow, but competition for positions is expected. The BLS projects employment for archivists, curators, and museum workers group to grow 9 percent from 2022 to 2032, faster than the average for all occupations. Demand is driven by the increasing volume of records, both physical and digital, that require management and preservation.

Growth may be stronger in areas related to digital archiving and electronic records management due to the explosion of digital information. Opportunities might also arise in specialized areas like corporate archives or community archives focused on preserving underrepresented histories.

However, funding constraints, especially in public sector and non-profit institutions, can limit the number of available positions. Candidates with a Master's degree, relevant internship experience, and specialized skills (particularly in digital preservation) will likely have the best prospects. Networking and active participation in professional organizations can also be beneficial.

Can I transition from librarianship or related fields?

Yes, transitioning from fields like librarianship, museum studies, records management, or history is common. These fields share overlapping skill sets, such as information organization, research skills, preservation awareness, and user service orientation. Many archivists hold MLS/MLIS degrees, the same qualification often held by librarians.

For those transitioning, highlighting transferable skills is key. Emphasizing experience with special collections, digital projects, metadata, preservation, or historical research can strengthen an application. Pursuing additional coursework or certifications specific to archives, such as the DAS certificate or archives-focused workshops, can bridge knowledge gaps.

Gaining practical archival experience, even through volunteering or short-term projects, is highly valuable. Networking with archivists and understanding the specific theories and practices unique to the archival profession (like appraisal, provenance, and original order) will aid the transition.

Are remote work opportunities available?

Remote work opportunities for archivists have increased, particularly accelerated by recent global events, but they are not universally available and often depend on the specific role and institution. Tasks involving digital processing, metadata creation, online reference services, grant writing, and administrative duties can potentially be done remotely.

However, core archival functions often require physical presence. Handling, processing, and preserving physical materials necessitates being on-site. Providing in-person reference assistance in a reading room is also a key on-site task for many positions.

Hybrid arrangements, combining remote and on-site work, are becoming more common. Fully remote positions are more likely in roles focused exclusively on digital archives, metadata services, or consulting. The availability of remote work varies greatly by employer and the nature of their collections.

How do archivists handle sensitive or controversial materials?

Archivists often encounter materials that are sensitive, controversial, or potentially upsetting due to their content (e.g., records depicting violence, discrimination, or containing private information). Handling such materials requires professionalism, ethical awareness, and established institutional policies.

Archivists aim to provide access while respecting privacy and minimizing harm. This may involve redacting sensitive personal data, providing warnings about potentially disturbing content, or establishing specific access conditions. Description practices strive for neutrality and accuracy, providing context without censoring or imposing personal judgments.

Institutional policies guide decisions on access restrictions, description, and handling procedures. Archivists rely on professional ethics codes and often consult with colleagues or advisory boards when dealing with particularly complex or challenging materials. Emotional resilience and professional detachment are important qualities when working with difficult records.

How has digitization affected the archivist profession?

Digitization has profoundly transformed the archivist profession. It has created new avenues for providing access to collections globally, allowing researchers and the public to engage with materials remotely. This has increased the visibility and potential impact of archives.

However, it has also introduced significant challenges. Digitization projects require technical expertise, specialized equipment, and considerable resources for scanning, metadata creation, and quality control. Furthermore, the resulting digital files require robust digital preservation strategies to ensure their long-term survival, adding a complex new layer to archival responsibilities.

The rise of "born-digital" records (those created electronically from the start) means archivists must now manage vast quantities of complex digital information, requiring skills in electronic records management, digital forensics, and data curation. While traditional skills remain essential, digital literacy and technical proficiency are now indispensable for nearly all archivists.

Explore the world of digital humanities and information management through online courses.

Helpful Resources

For those interested in learning more about the field of archives, several organizations and resources offer valuable information:

- Bureau of Labor Statistics: Archivists, Curators, and Museum Workers: Provides information on job duties, outlook, pay, and how to become one.

- Society of American Archivists (SAA): The leading professional organization in North America, offering resources, publications, continuing education, and ethical guidelines.

- SAA - What Is An Archivist?: An overview of the profession from the SAA.

- OpenCourser Learner's Guide: Find tips on how to leverage online courses for career development and skill building.

- OpenCourser - Library Science Category: Explore courses related to library and information science, often overlapping with archival studies.

Embarking on a career as an archivist requires dedication, a love for history and evidence, and adaptability in the face of technological change. It offers the unique reward of preserving the past and making it accessible for generations to come. Whether you are just beginning to explore this path or considering a transition, the journey into the world of archives is a commitment to safeguarding memory and knowledge.