Archaeologist

A Career as an Archaeologist: Unearthing the Past

Archaeology is the scientific study of human history and prehistory through the excavation of sites and the analysis of physical remains. It's a field that seeks to understand where humans came from, how societies developed, and the ways cultures evolved over time by examining the things people left behind, from tiny pottery shards to entire buried cities.

Working as an archaeologist often conjures images of adventure: uncovering ancient tombs, piecing together forgotten histories, and exploring remote corners of the globe. The reality involves meticulous research, careful documentation, and often, hard physical work, but the thrill of discovery and the contribution to understanding humanity's story remain powerful draws.

Introduction to Archaeology

This section provides a foundational understanding of archaeology, covering its definition, historical development, and core research goals, setting the stage for a deeper exploration of the career.

What is Archaeology? Defining the Scope

Archaeology delves into the human past by studying material culture—the physical objects, structures, and environmental modifications that past peoples created and used. This can range from ancient stone tools used millions of years ago to the remnants of 20th-century buildings. It's an inherently interdisciplinary field, drawing on history, anthropology, geology, biology, chemistry, and more to interpret finds.

The scope is vast, covering all periods of human existence across the entire globe. Archaeologists might specialize in specific time periods (like Classical Greece or Pre-Columbian America), geographic regions (like Egypt or Mesoamerica), or types of material culture (like ancient plant remains or ceramics). The ultimate goal is to reconstruct past lifeways, understand cultural change, and contribute to the broader narrative of human history.

Understanding the context of a find—where it was found, what it was found with, and the layers of soil surrounding it—is paramount. Context provides the crucial information needed to interpret an artifact's meaning and significance. Without context, an object is just an object; with context, it becomes a clue to the past.

These introductory courses offer a glimpse into the breadth and methods of archaeological inquiry.

For a concise overview, consider this introductory text.

A Brief History of the Discipline

While curiosity about the past and collecting ancient objects dates back millennia, archaeology as a systematic discipline is relatively young. Early "antiquarians" in the Renaissance began collecting and studying ancient artifacts, often focusing on classical Greece and Rome. However, it wasn't until the 19th century that more scientific methods began to emerge.

Pioneers like Christian Jürgensen Thomsen developed the "Three-Age System" (Stone Age, Bronze Age, Iron Age), providing a basic chronological framework. Figures like Flinders Petrie introduced meticulous excavation techniques and stressed the importance of recording context. The discovery of sites like Pompeii and Tutankhamun's tomb captured public imagination and spurred further interest.

The 20th century saw significant advancements, including the development of scientific dating techniques like radiocarbon dating (developed by Willard Libby, earning him a Nobel Prize), advancements in aerial photography, and the rise of theoretical approaches like processual ("New") archaeology and later post-processual archaeology, which emphasized interpretation and social context. Today, archaeology incorporates sophisticated technologies and grapples with complex ethical questions about heritage and representation.

These courses explore specific historical periods and civilizations through an archaeological lens.

Key Objectives of Archaeological Research

Archaeological research aims to answer fundamental questions about the human past. A primary objective is reconstructing culture history – outlining the sequence of cultures in a given region and describing how they changed over time. This involves identifying patterns in artifacts, architecture, and settlement locations.

Another key goal is reconstructing past lifeways. How did people live? What did they eat? What were their social structures, political organizations, and belief systems? Archaeologists use material remains as clues to piece together these aspects of daily life and societal organization, often drawing comparisons with living cultures studied by anthropologists.

Finally, archaeology seeks to understand and explain cultural processes. Why did societies change? What caused the rise and fall of civilizations? Why did agriculture develop? Archaeologists develop and test theories about cultural evolution, adaptation to environments, technological innovation, and social dynamics using the evidence gathered from the archaeological record.

These courses delve into specific research areas and the kinds of questions archaeologists seek to answer.

Role of an Archaeologist

This section outlines the day-to-day work, including fieldwork, lab analysis, and collaboration, providing a realistic view of the profession.

Daily Responsibilities and Fieldwork Tasks

The life of an archaeologist is often a mix of outdoor fieldwork, laboratory analysis, and office-based research and writing. Fieldwork, or excavation ("digs"), involves the systematic uncovering and recording of archaeological remains. This is often physically demanding work, involving digging with tools ranging from pick-axes and shovels for removing topsoil to trowels, brushes, and dental picks for delicate excavation.

Archaeologists meticulously record the context of every find, using methods like mapping, photography, and detailed note-taking. They might spend weeks or months at a site, often in remote locations and sometimes in challenging weather conditions. Fieldwork requires physical stamina, patience, attention to detail, and the ability to work well as part of a team.

Digs can take place anywhere in the world, from urban centers to remote jungles or deserts. The timing and duration depend on factors like funding, weather, and research goals. While fieldwork is a visible part of archaeology, many archaeologists spend significantly more time analyzing finds and data than they do excavating.

These resources provide insights into the practical aspects of archaeological work.

Laboratory Analysis and Artifact Preservation

Once artifacts and samples are recovered from the field, the work moves to the laboratory. Here, archaeologists clean, catalogue, and analyze the materials. This can involve identifying pottery types, analyzing stone tool manufacturing techniques, studying animal bones to understand past diets (zooarchaeology), or examining ancient plant remains (paleoethnobotany).

Specialized analyses might include chemical testing, microscopic examination, or dating techniques like radiocarbon dating. Conservation is also a critical component, involving the stabilization and preservation of fragile artifacts to prevent decay. This requires specialized knowledge and careful handling.

Lab work demands meticulous organization, analytical skills, and often, collaboration with specialists in other scientific fields. The data generated from lab analysis forms the basis for interpreting the site and understanding the lives of the people who inhabited it.

These resources touch upon the analysis and interpretation phases of archaeology.

Collaboration and Community Engagement

Archaeology is rarely a solitary pursuit. Field projects typically involve teams of specialists, including surveyors, illustrators, conservators, and various scientific experts (geologists, botanists, osteologists). Collaboration extends beyond the immediate team; archaeologists often work closely with historians, anthropologists, and other scholars to build a more complete picture of the past.

Increasingly, collaboration with local and descendant communities, particularly Indigenous groups, is recognized as essential. This involves respecting cultural heritage, incorporating local knowledge, and ensuring that research benefits and involves the communities connected to the sites being studied. Ethical engagement, communication, and relationship-building are crucial skills.

Archaeologists also engage with the public through museum exhibits, site tours, publications, and educational programs, sharing their findings and promoting the importance of heritage preservation. Effective communication skills are vital for disseminating research and fostering public support.

These courses touch upon interdisciplinary connections and the societal role of archaeology.

Formal Education Pathways

Understanding the educational requirements is crucial for anyone planning a career in archaeology. This section details the typical academic journey.

Pre-University Preparation

While specific requirements vary, a strong foundation in high school is beneficial. Courses in history, geography, and social studies provide essential background knowledge about past societies and environments. Science courses, particularly biology, chemistry, and earth science, are valuable for understanding analytical techniques and environmental contexts.

Developing strong writing and critical thinking skills through English and literature courses is also crucial, as archaeologists need to analyze information and communicate their findings effectively. Mathematics provides a basis for understanding quantitative methods used in data analysis and surveying.

Exploring related subjects like art history or anthropology can also provide valuable perspectives. Volunteering at local museums or historical societies, or participating in introductory archaeology programs if available, can offer early exposure to the field.

Undergraduate and Graduate Degrees

A bachelor's degree (BA or BS) is typically the minimum requirement to participate in archaeological fieldwork, often as a field technician or assistant. Most students major in Anthropology or Archaeology. Related fields like History, Classics, or Geology can also provide relevant backgrounds, often supplemented with specific archaeology courses and field school experience.

However, to advance professionally and lead projects, manage research, or work in specialized roles, a graduate degree is usually necessary. A Master's degree (MA or MS) in Archaeology or Anthropology (often with an archaeology focus) is typically required for positions in Cultural Resource Management (CRM), government agencies, and museums. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), a master's degree is the typical entry-level education.

Graduate programs involve advanced coursework, specialized training, research, and often, a thesis based on original fieldwork or analysis. Field school experience, gained either during or after the undergraduate degree, is almost always a prerequisite for graduate study and professional work.

These courses cover foundational topics often encountered in undergraduate and graduate studies.

Research Specializations and Fieldwork

A Ph.D. is generally required for university teaching positions and high-level research roles, including directing major international projects or leading museum research departments. Doctoral programs involve intensive research, specialized coursework, comprehensive exams, and culminate in a dissertation presenting significant original research.

During graduate studies, students typically develop one or more specializations. These might be geographic (e.g., Andean South America, Roman Britain), temporal (e.g., Neolithic period, Industrial archaeology), or methodological (e.g., zooarchaeology, lithic analysis, geoarchaeology, maritime archaeology). Gaining extensive fieldwork experience is critical throughout graduate school.

Choosing a specialization often depends on personal interests, faculty expertise at the chosen university, and job market demands. Developing strong analytical skills, research capabilities, and a publication record are essential for academic and research-focused careers.

These resources explore specific regions and analytical approaches relevant to specialization.

Online Learning and Skill Development

Beyond formal degrees, online resources and self-directed learning can play a significant role in building foundational knowledge and specialized skills for archaeology.

Online Resources for Foundational Knowledge

Online courses provide accessible ways to explore archaeological topics, supplement formal education, or gain knowledge for career transitions. Many universities and institutions offer introductory courses covering archaeological methods, world prehistory, or specific ancient civilizations. These can be valuable for gaining foundational understanding before committing to a full degree program or for lifelong learners interested in the subject.

Platforms like OpenCourser allow learners to browse history courses or specifically search for archaeology offerings from various providers. Learners can explore syllabi, read reviews, and compare courses to find those that match their interests and learning goals. Topics like ancient history, art history, anthropology, and specific cultural studies are widely available online.

While online courses may not replace the hands-on experience of a field school or the depth of a formal degree, they are excellent tools for building knowledge, exploring different facets of the field, and demonstrating initiative to potential graduate programs or employers.

These courses offer introductions to diverse archaeological subjects suitable for online learning.

Self-Guided Projects and Practical Experience

While structured field schools are essential, aspiring archaeologists can gain valuable experience through self-guided projects or volunteering. Documenting local historical sites (with permission), researching local history through archives, or volunteering at a museum's collections department can provide practical insights.

Learning relevant software skills is also highly beneficial. Proficiency in Geographic Information Systems (GIS), database management, statistical software, or 3D modeling programs can enhance employability. Many online tutorials and courses are available for learning these technical skills.

Engaging with local archaeological societies or attending public lectures and conferences can provide networking opportunities and exposure to current research. Contributing to citizen science projects related to archaeology or history can also be a way to get involved.

These resources touch upon skills and areas relevant to practical application.

Certifications and Enhancing Employability

While formal degrees are paramount, certain certifications can enhance employability, particularly in specialized areas or within Cultural Resource Management (CRM). Certifications in GIS, technical illustration, or conservation might be beneficial depending on career goals.

Membership in professional organizations like the Society for American Archaeology (SAA) or the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA) demonstrates professional commitment. The Register of Professional Archaeologists (RPA) offers registration based on education and experience standards, which can be a requirement or preference for some employers, particularly in CRM.

Developing transferable skills is also key. These include project management, technical writing, data analysis, critical thinking, and communication. Highlighting these skills, gained through coursework, fieldwork, or other experiences, can be advantageous, especially for those transitioning from other careers.

Career Progression and Opportunities

This section explores typical career paths, potential specializations, and the overall job market for archaeologists.

Entry-Level Roles

With a bachelor's degree and field school experience, entry-level positions often involve working as a Field Technician or Archaeological Assistant. These roles typically involve participating in excavations, surveys, artifact processing, and basic documentation under the supervision of more experienced archaeologists.

These positions are common in Cultural Resource Management (CRM) firms, which conduct archaeological assessments required by historic preservation laws before construction or development projects. Government agencies and university research projects may also hire field technicians on a project-by-project basis.

Entry-level work is often seasonal or project-based and can involve significant travel and physically demanding labor. It provides crucial hands-on experience necessary for career advancement.

Mid-Career Specializations

With a graduate degree (typically a Master's) and several years of experience, archaeologists can advance to supervisory roles like Field Director or Project Archaeologist. They may lead field crews, manage smaller projects, conduct specialized analyses, and contribute to report writing.

This stage often involves developing a specialization, such as expertise in a particular type of artifact (e.g., ceramics, lithics), a specific analytical technique (e.g., zooarchaeology, archaeobotany), or a particular area like historical archaeology, underwater archaeology, or bioarchaeology (the study of human remains).

Mid-career professionals might work in CRM, government agencies (federal, state, tribal), museums, or academic research labs. Strong project management, analytical, and writing skills become increasingly important.

These courses cover areas that could become mid-career specializations.

Senior Positions and Outlook

Senior archaeologists, often holding PhDs or extensive Master's-level experience, may occupy roles such as Principal Investigator (PI) in CRM firms, senior government archaeologists, museum curators, or university professors. PIs manage large-scale projects, oversee research design, analysis, and reporting, handle budgets, and liaise with clients and agencies.

University professors conduct research, teach undergraduate and graduate courses, mentor students, and seek grant funding. Museum curators manage collections, develop exhibits, conduct research, and engage in public outreach. Senior government roles often involve policy development, regulatory oversight, and management of public lands' cultural resources.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported the median annual wage for anthropologists and archaeologists was $61,910 in May 2021. Employment is projected to grow 6% from 2021 to 2031, about average. However, the field remains competitive, especially for academic positions. Experience, advanced degrees, and specialized skills are advantageous. Geographic demand varies, with CRM jobs often linked to development activities.

Tools and Technologies in Modern Archaeology

Archaeology increasingly relies on sophisticated technologies to survey sites, analyze artifacts, and manage data.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS)

GIS has become an indispensable tool in archaeology. It allows researchers to map site locations, artifact distributions, and environmental features, integrating diverse spatial datasets. Archaeologists use GIS for site prediction modeling, analyzing settlement patterns, mapping excavation units, and managing vast amounts of spatial data collected during surveys and digs.

By layering data like topography, soil types, water sources, and known site locations, GIS helps identify areas with high archaeological potential. It's also crucial for visualizing landscape changes over time and understanding the relationship between human activities and the environment. Proficiency in GIS is a highly valuable skill for archaeologists today, particularly in CRM.

Many projects use GIS to create detailed digital maps of excavation sites, precisely recording the location of features and artifacts in three dimensions. This facilitates analysis and helps preserve the spatial context crucial for interpretation.

These courses provide introductions to GIS concepts and applications.

Remote Sensing and 3D Modeling

Remote sensing techniques allow archaeologists to investigate landscapes and identify potential sites without extensive excavation. Aerial photography, satellite imagery, and LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) can reveal subtle surface features like ancient field systems, earthworks, or building foundations hidden by vegetation or time.

Geophysical survey methods, such as ground-penetrating radar (GPR), magnetometry, and electrical resistivity, use instruments to detect buried features beneath the ground surface, helping target excavation efforts more effectively. These non-invasive techniques minimize site disturbance.

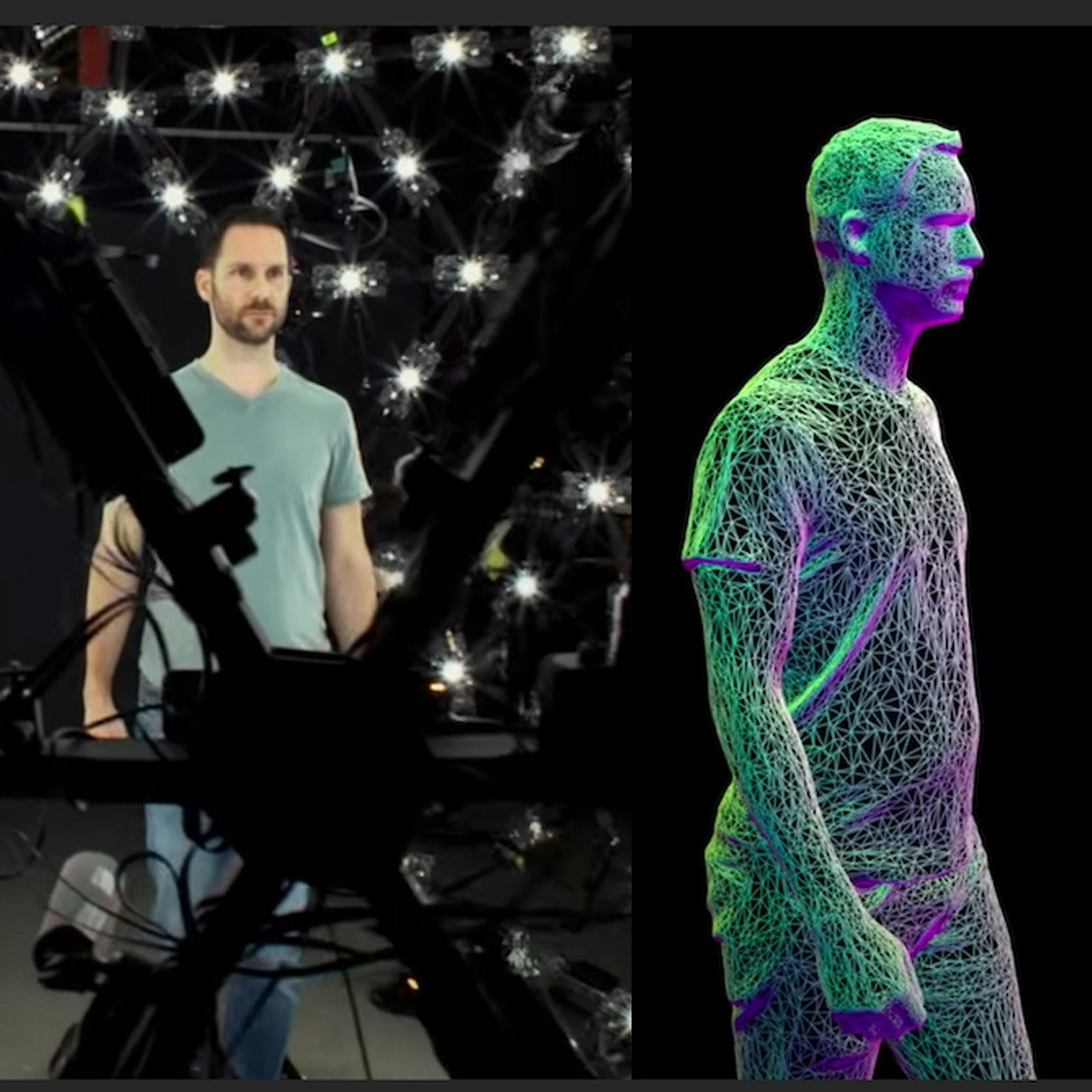

3D scanning and photogrammetry are used to create detailed digital models of artifacts, features, and entire sites. These models aid in analysis, conservation, documentation, and public engagement through virtual reconstructions and online exhibits.

These courses touch on related imaging and modeling techniques.

Dating Methods ELI5: How Do We Know How Old Things Are?

Imagine time like a clock, but for very old things. Archaeologists use special "clocks" hidden in objects to figure out their age. One famous clock is called Radiocarbon Dating, or Carbon-14 dating. Everything alive (plants, animals, people) takes in a tiny bit of radioactive carbon (Carbon-14) from the air. Think of it like breathing in special air.

When something dies, it stops breathing in this special air. The Carbon-14 inside it starts to disappear, very, very slowly, at a speed we know exactly. It's like a clock ticking down. By measuring how much Carbon-14 is left in something old (like a piece of wood or bone), scientists can calculate how long ago it died. This clock works well for things up to about 50,000-60,000 years old.

Another way is looking at layers of dirt, like layers in a cake. This is called Stratigraphy. Usually, the deepest layers are the oldest, and the layers closer to the surface are younger. If archaeologists find an object in a deep layer, they know it's probably older than things found in layers above it. By studying these layers and the objects within them, they build a timeline.

There are other methods too, like dating pottery based on its style (styles change over time, like fashion!) or using other radioactive clocks for even older things like rocks (useful for dating geological layers around human fossils). Combining different methods helps make the dates more accurate.

These resources explore dating and related scientific concepts.

Ethical Considerations

Modern archaeology grapples with significant ethical responsibilities concerning cultural heritage, descendant communities, and the archaeological record itself.

Cultural Heritage Preservation

Archaeologists act as stewards of the past. A core ethical principle is the preservation and protection of the archaeological record, which includes sites, artifacts, and associated data. This involves advocating for site protection, using minimally invasive techniques where possible, and ensuring proper long-term curation of excavated materials and records.

Many countries have laws protecting archaeological sites and cultural heritage (often called Cultural Resource Management or CRM laws in the US). Archaeologists must comply with these regulations, which often mandate archaeological surveys and mitigation efforts before development projects can proceed. This work forms the bulk of employment for archaeologists today.

Preservation also involves combating the looting of archaeological sites and the illicit trade in antiquities, which destroy context and rob humanity of its shared heritage. Archaeologists generally refrain from authenticating or appraising artifacts for commercial purposes to avoid encouraging the market.

These courses touch upon heritage preservation and management.

Collaboration with Indigenous and Descendant Communities

Recognizing that the archaeological record often represents the heritage of living communities is a fundamental ethical consideration. This is particularly crucial when working with Indigenous heritage. Ethical practice requires meaningful consultation and collaboration with descendant communities.

This includes seeking free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) before beginning research that affects their heritage, respecting sacred sites and traditional knowledge, and involving community members in the research process, interpretation, and dissemination of results whenever possible. Collaboration should aim for equitable partnerships and recognize Indigenous sovereignty over cultural heritage.

The excavation and study of human remains are especially sensitive. Archaeologists must respect the beliefs and wishes of descendant communities regarding the treatment of ancestral remains, balancing scientific inquiry with cultural sensitivities and legal requirements like NAGPRA (Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act) in the United States.

These courses address cultural interactions and Indigenous perspectives.

Artifact Repatriation and Data Sharing

The question of who owns the past is complex. Many artifacts, particularly those acquired during colonial periods, reside in museums far from their places of origin. Repatriation, the return of cultural artifacts and human remains to their originating communities or nations, is a major ethical debate.

Archaeologists are often involved in discussions and research related to repatriation claims, navigating legal frameworks and ethical responsibilities. There is a growing consensus on the importance of returning culturally significant items and ancestral remains upon request from legitimate claimants.

Ethical practice also emphasizes accountability and the sharing of knowledge. This includes timely publication of research findings, making data accessible to other researchers and the public (while respecting sensitivities), and ensuring that archaeological collections are properly curated and available for future study and educational purposes.

These resources discuss cultural property and related historical contexts.

Challenges Faced by Archaeologists

Despite its appeal, a career in archaeology comes with significant challenges related to funding, environmental threats, and the structure of the profession.

Funding and Project Instability

Archaeological research, whether academic or CRM-based, often relies on grants, contracts, or government funding. Securing funding can be highly competitive and time-consuming. Academic research grants are limited, while CRM work is tied to the cycles of the construction and development industries.

This can lead to project instability and periods of unemployment or underemployment, particularly for those in entry-level or project-based positions. Budget cuts affecting government agencies, universities, and cultural institutions can directly impact archaeological projects and job opportunities.

The need to constantly seek funding can detract from research time and create uncertainty. Financial constraints can also limit the scope of research, the application of expensive technologies, or the ability to provide long-term site conservation.

Climate Change and Site Preservation

Climate change poses a severe threat to the archaeological record worldwide. Rising sea levels and increased coastal erosion threaten coastal and underwater sites. Melting glaciers and permafrost expose fragile organic artifacts that quickly degrade if not recovered and conserved immediately.

Changes in rainfall patterns, increased frequency of extreme weather events (floods, droughts, wildfires), and shifting vegetation zones can damage or destroy sites both known and undiscovered. The drying of wetlands, which preserve organic materials exceptionally well, leads to the loss of invaluable information about past environments and human life.

Archaeologists face the challenge of documenting and mitigating these impacts with limited resources. Decisions about which threatened sites to prioritize for excavation or protection are often difficult. Climate change research itself, however, also represents an area where archaeological data on past human adaptation can provide valuable long-term perspectives.

Academic vs. Commercial Archaeology

The field is often broadly divided into academic archaeology (based in universities and museums) and commercial or Cultural Resource Management (CRM) archaeology (conducted by private firms or government agencies in compliance with preservation laws). While both share core methods, their goals, timelines, and funding structures differ.

CRM archaeology constitutes the majority of archaeological work today but is driven by development schedules and regulatory compliance rather than purely research-driven questions. This can sometimes create tension, with tight deadlines and budgets potentially limiting the scope of investigation or analysis compared to academic projects.

Conversely, academic positions are scarce and highly competitive. Bridging the gap between academic research interests and the practical demands of CRM, and ensuring high standards across all sectors of the profession, remain ongoing challenges.

Future of Archaeology

The field of archaeology is continually evolving, embracing new technologies and adapting to contemporary global challenges.

AI and Machine Learning Applications

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning are beginning to transform archaeological research. AI algorithms can analyze vast datasets, such as satellite imagery or LiDAR scans, to predict the locations of undiscovered sites more efficiently than manual review.

AI is also being applied to artifact analysis, helping to classify pottery shards, decipher damaged ancient texts, or analyze complex datasets from scientific instruments. Natural Language Processing (NLP) can aid in analyzing historical texts and archaeological reports on a large scale.

While still an emerging area, AI holds the potential to automate time-consuming tasks, reveal hidden patterns in data, and enhance archaeologists' ability to interpret the past. However, ethical considerations regarding data bias and interpretation remain important.

These resources discuss the intersection of technology and humanities.

Digital Engagement and Public Outreach

Digital technologies are creating new avenues for public engagement. 3D models of artifacts and sites can be shared online, allowing virtual visits and interactions. Digital reconstructions can bring ancient landscapes and structures to life for broader audiences.

Online databases and open-access publications make archaeological data and research findings more accessible. Social media and blogs provide platforms for archaeologists to communicate directly with the public, share discoveries, and discuss the relevance of the past to contemporary issues.

This increased digital engagement can foster greater public appreciation for heritage, encourage support for preservation efforts, and make archaeology more inclusive and participatory.

Adapting to Climate Change Priorities

As climate change impacts accelerate, archaeological priorities are shifting. There is a growing focus on "rescue archaeology" – documenting and excavating sites threatened by erosion, melting ice, or other climate-related factors before they are lost forever.

Archaeology is also increasingly contributing to climate change research itself. The study of past human responses to environmental shifts provides long-term perspectives on adaptation, resilience, and societal collapse, offering potential lessons for the present.

Developing sustainable archaeological practices, reducing the carbon footprint of fieldwork and lab work, and advocating for the protection of climate-vulnerable heritage are becoming integral parts of the discipline's future.

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are answers to some common questions about pursuing a career in archaeology.

Is a PhD required to work in archaeology?

Not necessarily, but it depends on your career goals. A bachelor's degree with a field school is often sufficient for entry-level field technician roles. A Master's degree is typically required for supervisory positions, project management in CRM, museum work, and government jobs. A PhD is generally necessary for university teaching, high-level research positions, and often for working internationally.

How competitive are field positions?

The field, especially for permanent positions and academic roles, is generally competitive. Entry-level field technician jobs, particularly in CRM, can be numerous but are often temporary or project-based. Advancement requires further education, experience, and specialized skills. Networking and gaining diverse fieldwork experience are crucial.

Can I transition from an unrelated degree?

Yes, transitions are possible, but typically require supplemental education and experience. If your bachelor's degree is in an unrelated field, you might need to take post-baccalaureate courses in archaeology and anthropology and attend an archaeological field school before applying to graduate programs. Highlighting transferable skills (e.g., project management, data analysis, writing, technical skills like GIS) from your previous career can be advantageous.

What physical demands are involved?

Fieldwork can be physically demanding. It often involves hiking, lifting, bending, kneeling, and working outdoors for extended periods in various weather conditions (heat, cold, rain). Excavation itself involves manual labor like shoveling and hauling dirt. While excellent physical condition helps, stamina, adaptability, and a willingness to work in potentially uncomfortable environments are key. Lab work is less physically strenuous but requires focus and attention to detail.

Are international opportunities common?

Opportunities exist but often require advanced degrees (usually a PhD), specialized expertise, language skills, and significant experience. Many international projects are run by universities or research institutions, making these positions highly competitive. Some CRM firms may undertake international projects, but these are less common than domestic work. Obtaining permits and navigating regulations for international work can also be complex.

How does archaeology intersect with law?

Archaeology intersects with law primarily through cultural heritage and historic preservation legislation. In many countries, laws mandate archaeological assessment before development projects (CRM). Archaeologists work to ensure compliance with these laws (e.g., Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act in the US). Laws like NAGPRA govern the treatment and repatriation of Native American human remains and cultural items. International law and conventions (like UNESCO conventions) address issues of illicit trafficking of artifacts and protection of world heritage sites.

Embarking on a career in archaeology requires passion, dedication, and a significant investment in education and experience. It offers the unique reward of uncovering and interpreting the human past, contributing to our collective understanding of where we came from. While challenges exist, for those drawn to history, discovery, and meticulous research, it can be a deeply fulfilling path. Explore resources on OpenCourser to further investigate relevant courses and topics.