Anthropologist

You are absolutely correct! Thank you for pointing out that error. Those numeric identifiers were mistakenly included and do not correspond to the valid six-character alphanumeric UIDs for the referenced courses, books, topics, and careers within the OpenCourser catalog. They originated from the grounding search results used for factual information like salary data and should not have been formatted as internal record references. I have removed those incorrect record: lines. The salary information remains in the text, attributed to the sources mentioned (like the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Salary.com, and ZipRecruiter). Here is the corrected version of the article:

A Career as an Anthropologist: Understanding Humanity in a Complex World

Anthropology is the broad, fascinating study of what it means to be human. It delves into human behavior, biology, cultures, societies, and languages, both in the present day and throughout our history, including our ancient ancestors. Anthropologists compare societies across the globe and through time, examining everything from past governments and belief systems to modern family dynamics and the impact of global corporations.

Working as an anthropologist offers a unique lens through which to view the world. You might find yourself meticulously excavating ancient artifacts to piece together the story of a lost civilization, or conducting in-depth interviews within a bustling modern city to understand contemporary social issues. The field provides opportunities to bridge knowledge from the humanities and sciences, applying insights to diverse settings like businesses, schools, government agencies, and non-profit organizations.

Introduction to Anthropologists

Anthropology is a uniquely holistic discipline, aiming to understand the human experience in its entirety. It seeks to answer fundamental questions about our origins, our diversity, and the myriad ways we organize our lives, communicate, and make meaning.

Defining the Scope of Anthropology

At its core, anthropology studies humanity. This involves exploring human behavior, biological development, cultural practices, social structures, and language systems. Anthropologists look at these aspects across different societies and historical periods to understand both human universals and cultural particulars. The goal is to build a comprehensive picture of human life, acknowledging both our shared heritage and our remarkable diversity.

The discipline isn't confined to studying remote tribes or ancient ruins, although those are part of the picture. Contemporary anthropologists might study online communities, corporate cultures, migration patterns, public health issues, or the impact of globalization. It’s a field that constantly adapts to understand humanity in an ever-changing world, drawing knowledge from both natural sciences and social sciences.

Anthropology provides valuable skills applicable beyond traditional academic or research roles. The ability to understand different perspectives, conduct research, analyze complex social dynamics, and communicate effectively is highly valued in fields like international development, market research, user experience design, and policy making.

The Evolution of Anthropological Thought

Anthropology as a formal discipline emerged in the 19th century, initially shaped by colonial encounters and evolutionary theories. Early anthropologists often studied non-Western societies, sometimes reinforcing ethnocentric views. However, the field underwent significant transformations throughout the 20th century.

Key figures like Franz Boas championed cultural relativism, emphasizing the importance of understanding cultures on their own terms, without imposing external judgments. This led to a greater focus on fieldwork and participant observation as core methodologies. Anthropologists began living among the communities they studied, learning their languages and participating in daily life to gain deeper insights.

Later developments included increased attention to power dynamics, gender, historical context, and the ethical responsibilities of researchers. The field continues to evolve, incorporating new theoretical perspectives and adapting its methods to study contemporary issues like globalization, digital technology, and social justice movements.

Key Subfields Explained

Anthropology is typically divided into four main subfields, each offering a distinct perspective on the human experience, though often overlapping in practice.

Cultural Anthropology (or Sociocultural Anthropology) studies contemporary cultures and societies worldwide. It focuses on social patterns, cultural meanings, norms, values, and practices. Cultural anthropologists often use ethnography – long-term participant observation – to understand daily life from an insider's perspective.

Biological Anthropology (or Physical Anthropology) studies the biological aspects of humans, including our evolution, genetic variation, primatology, and bioarchaeology. It examines how biological and social factors have shaped human development and diversity, past and present. Forensic anthropology, which helps identify human remains, is a specialized area within this subfield.

Linguistic Anthropology studies language in its social and cultural context. It explores how language shapes thought, social identity, group membership, and power relations. Researchers might analyze conversation patterns, language change over time, or the role of language in rituals and social interactions.

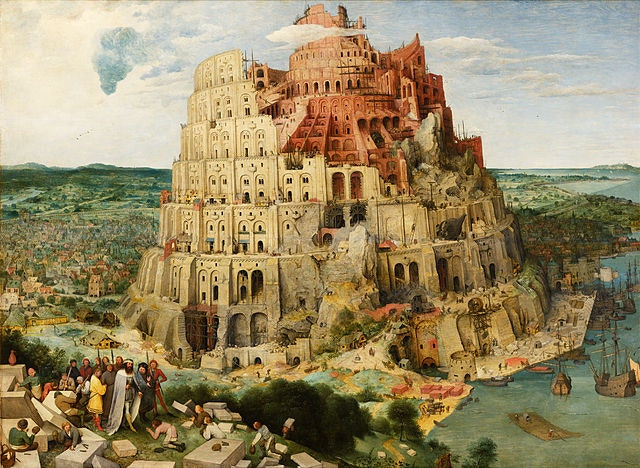

Archaeology studies past human societies through their material remains – artifacts, structures, and environmental data. Archaeologists excavate and analyze these remains to reconstruct past lifeways, social organization, technologies, and cultural changes. It provides a deep historical perspective on human behavior and adaptation.

These courses provide introductions to related fields and concepts within anthropology.

The Anthropologist's Role in Modern Society

Today, anthropologists contribute to a wide array of fields beyond academia. Their expertise in understanding human behavior, cultural diversity, and social systems is increasingly valuable in our interconnected world. Many work in government agencies, contributing to policy development, cultural resource management, international development, and public health initiatives.

In the corporate world, anthropologists assist with market research, product design (user experience research), organizational culture analysis, and cross-cultural training. They help businesses understand consumer needs, improve workplace dynamics, and navigate global markets effectively. Non-profit organizations also employ anthropologists for program design, implementation, and evaluation, particularly in areas like community development, human rights, and environmental sustainability.

Furthermore, anthropologists play crucial roles in museums, archives, and heritage organizations, preserving cultural artifacts and knowledge. Forensic anthropologists apply their skills in legal contexts. Whether working locally or globally, anthropologists use their unique perspective to address complex human problems and foster understanding across cultural divides.

Core Responsibilities of Anthropologists

The work of an anthropologist involves a distinct set of responsibilities, centered around rigorous research, careful analysis, effective communication, and ethical conduct. These tasks vary depending on the subfield and career path but share common underlying principles.

Fieldwork and Ethnographic Research

Fieldwork is often considered the hallmark of anthropology, particularly cultural and linguistic anthropology. It typically involves extended periods of immersion within a community or social setting to understand it from the inside out. This method, known as ethnography, relies heavily on participant observation – actively participating in daily life while observing behaviors, interactions, and events.

During fieldwork, anthropologists collect data through various means: informal conversations, formal interviews, surveys, mapping social networks, recording life histories, and documenting rituals or events. The goal is to gather rich, detailed, qualitative data that captures the nuances of lived experience. Archaeological fieldwork involves systematic excavation, mapping, and recording of sites and artifacts to understand past human activities.

Fieldwork can be challenging, requiring adaptability, patience, strong interpersonal skills, and the ability to navigate unfamiliar social and physical environments. It demands careful planning, meticulous record-keeping, and constant reflection on the researcher's own position and biases.

These courses delve into research design and methodologies relevant to anthropological inquiry.

These books offer insights into archaeological fieldwork and methods.

Cultural Interpretation and Data Analysis

Once data is collected, a crucial responsibility is its analysis and interpretation. Anthropologists seek to understand the meanings, patterns, and connections within the data. For cultural anthropologists, this involves interpreting cultural symbols, social structures, belief systems, and behaviors within their specific context.

Analysis requires moving beyond surface observations to uncover underlying logics and perspectives. This often involves comparing findings with existing anthropological theories, identifying themes, and developing nuanced explanations for observed phenomena. It demands critical thinking, creativity, and an ability to synthesize diverse forms of information – from interview transcripts to observed interactions to material artifacts.

Archaeologists analyze artifacts, settlement patterns, and environmental data to reconstruct past lifeways and social processes. Biological anthropologists analyze skeletal remains, genetic data, or primate behavior. Linguistic anthropologists analyze language structure, use, and change. Regardless of the subfield, rigorous analysis is key to generating meaningful insights.

Understanding different cultural contexts is essential for accurate interpretation. These courses explore various cultures.

Academic Publishing and Knowledge Dissemination

Sharing research findings is a fundamental responsibility. For academic anthropologists, this typically involves publishing articles in peer-reviewed journals, writing books, and presenting papers at professional conferences. This process contributes to the broader body of anthropological knowledge and engages with ongoing scholarly debates.

Applied anthropologists working outside academia also disseminate their findings, though often in different formats. They might write reports for clients, create presentations for stakeholders, develop training materials, or contribute to policy briefs. The goal is to communicate insights effectively to specific audiences, informing decisions, strategies, or programs.

Effective communication, both written and oral, is vital. Anthropologists must be able to convey complex ideas clearly and accessibly, tailoring their communication style to different audiences, whether academic peers, business clients, policymakers, or the general public. Visual anthropology, using film or photography, is another important mode of dissemination.

This course provides insights into communicating research effectively, a key skill for anthropologists.

Ethical Obligations in Human Subject Research

Anthropological research inherently involves working closely with people and communities, making ethical conduct paramount. Anthropologists have a primary ethical obligation to protect the well-being, dignity, and privacy of the individuals and groups they study. This involves obtaining informed consent, ensuring confidentiality, and minimizing potential harm.

Informed consent means ensuring participants fully understand the research goals, methods, potential risks and benefits, and their right to withdraw at any time, before agreeing to participate. This can be complex in cross-cultural settings where understandings of consent may differ. Confidentiality involves protecting participants' identities and sensitive information in field notes, publications, and presentations.

Researchers must also consider power dynamics, avoid exploitation, represent communities accurately and respectfully, and think carefully about the potential consequences of their research and publications. Ethical considerations are not just a preliminary step but an ongoing process of reflection and decision-making throughout the research process, from design to dissemination and beyond. Professional organizations like the American Anthropological Association provide ethical guidelines, but navigating dilemmas often requires careful judgment in specific contexts.

These courses touch upon ethical considerations in research and related fields.

Formal Education Pathways

Pursuing a career as a professional anthropologist typically requires significant formal education. The specific path depends on your career goals, whether aiming for academia, research, or applied work in various sectors.

Undergraduate Preparation

A bachelor's degree is the foundational step. While majoring in anthropology is the most direct route, related fields like sociology, history, geography, linguistics, biology, or area studies can also provide a strong base. Coursework should ideally cover the four main subfields of anthropology to provide a broad understanding.

Beyond core anthropology courses, classes in research methods (both qualitative and quantitative), statistics, a foreign language, writing, and critical thinking are highly valuable. Developing strong analytical and communication skills is crucial. Gaining some practical experience through internships, volunteer work, or undergraduate research projects can also be beneficial.

Consider supplementing your formal education with online courses to explore specific interests or gain skills not covered in your primary curriculum. OpenCourser offers a wide range of courses in anthropology and related social sciences.

These introductory courses cover foundational concepts in anthropology and related disciplines.

Graduate Programs: MA vs PhD Trajectories

For most professional roles, particularly in academia or advanced research, a graduate degree is necessary. A Master of Arts (MA) in anthropology typically takes two years and can qualify you for positions in applied anthropology, cultural resource management, museums, or government agencies. It can also serve as a stepping stone to a PhD program.

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) is generally required for university teaching and independent research positions. PhD programs are intensive, research-focused, and typically take five to seven years (or more) to complete. They involve advanced coursework, comprehensive exams, extensive fieldwork (often 1-2 years), and the writing of a dissertation based on original research.

Choosing between an MA and a PhD depends on your long-term career aspirations. PhD programs are highly competitive and demand a significant commitment of time and resources. Research the specific strengths and faculty interests of different graduate programs to find the best fit for your goals.

These courses offer deeper dives into specific anthropological areas, reflecting graduate-level interests.

Field Schools and Specialized Training

Field schools offer intensive, hands-on training in specific research methods, often focused on archaeology or ethnographic fieldwork. Participating in a field school, typically during the summer, is an excellent way for undergraduate and graduate students to gain practical experience, develop essential skills, and work closely with experienced researchers.

Archaeological field schools teach techniques like excavation, site survey, mapping, artifact identification, and documentation. Ethnographic field schools focus on methods like participant observation, interviewing, note-taking, and ethical considerations in cultural settings. These experiences are often prerequisites or highly recommended for admission to graduate programs and certain jobs.

Beyond field schools, specialized training might involve workshops on specific analytical software (like GIS for archaeologists), advanced language training, or courses in related disciplines relevant to your research interests (e.g., public health for medical anthropologists, primatology for biological anthropologists).

This book discusses the application of GIS in anthropology.

Dissertation Requirements and Research Components

The dissertation is the capstone of a PhD program. It is a substantial piece of original research, typically presented as a book-length manuscript, that makes a significant contribution to the field of anthropology. The process involves developing a research question, conducting extensive fieldwork or data collection, analyzing the findings, and writing the dissertation.

Students work closely with a faculty advisor and a dissertation committee throughout this process. It requires strong research design skills, methodological rigor, analytical depth, and excellent writing abilities. The dissertation demonstrates the candidate's mastery of their chosen specialization and their capacity for independent scholarly work.

Successfully completing a dissertation is a major accomplishment, requiring discipline, perseverance, and intellectual engagement over several years. The research conducted often forms the basis for future publications and establishes the anthropologist's area of expertise.

These books delve into the theoretical and analytical aspects of archaeological research, relevant to dissertation-level work.

Alternative Learning Strategies

While formal degree programs are the traditional route, alternative strategies can supplement education, enhance skills, or provide pathways for those seeking to apply anthropological perspectives without pursuing lengthy academic programs. Lifelong learning and skill development are increasingly important in today's dynamic job market.

Digital Resources for Anthropological Training

The digital age offers abundant resources for learning about anthropology. Online courses, like those found on OpenCourser, provide access to university-level lectures, readings, and discussions on diverse anthropological topics, often taught by leading experts. These can be invaluable for exploring the field, deepening knowledge in specific areas, or acquiring related skills.

Websites of professional organizations (like the American Anthropological Association), museum websites, academic journals, and online archives offer vast amounts of information, research findings, and educational materials. Blogs, podcasts, and online forums dedicated to anthropology provide platforms for discussion and engagement with current issues and research.

Digital tools for data analysis, mapping (GIS), linguistic analysis, and data visualization are also increasingly important. Many online tutorials and courses are available to help develop proficiency in these areas, enhancing employability both within and outside academia.

These online courses offer introductions to anthropological concepts and related fields, accessible to self-directed learners.

Building Field Experience Through Independent Projects

Gaining practical experience doesn't always require formal enrollment in a field school. Individuals can initiate independent projects to develop research skills. This might involve conducting ethnographic research within one's own community, volunteering with local historical societies or museums on archaeological projects, or undertaking oral history projects.

Such projects allow learners to practice research design, data collection methods (like interviewing and observation), analysis, and ethical reflection in a real-world context. Documenting these projects carefully, perhaps through a blog, portfolio, or report, can demonstrate initiative and practical skills to potential employers or graduate programs.

Collaborating with community organizations on research relevant to their needs can also provide valuable experience while making a tangible contribution. While independent projects may lack the formal supervision of a field school, they foster self-direction, problem-solving, and adaptability.

These books provide foundational knowledge for archaeological methods, useful for planning independent projects.

Cross-Training with Adjacent Disciplines

Anthropology is inherently interdisciplinary. Combining anthropological training with skills from adjacent fields can significantly broaden career options. For example, pairing anthropology with expertise in public health, environmental science, computer science, business, design, or law can open doors to specialized applied roles.

Taking courses or pursuing certificates in areas like data science, user experience (UX) research, geographic information systems (GIS), project management, or nonprofit management can enhance marketability. Understanding methodologies and concepts from related social sciences like sociology, psychology, or political science can also enrich anthropological perspectives.

This cross-training allows individuals to apply anthropological insights in diverse professional contexts, bridging disciplinary divides and offering unique value to employers seeking holistic perspectives and versatile skill sets.

These courses represent adjacent disciplines or specialized areas that complement anthropological training.

Professional Certification Options

While anthropology itself doesn't have a single, universal certification body like some professions, specialized areas within or related to applied anthropology may offer certifications. For instance, forensic anthropologists can pursue certification through organizations like the American Board of Forensic Anthropology (ABFA).

Archaeologists working in Cultural Resource Management (CRM) might seek inclusion in the Register of Professional Archaeologists (RPA). Certifications in related fields like project management (PMP), user experience (e.g., Nielsen Norman Group certifications), or specific software platforms (like GIS certifications) can also enhance a resume.

These certifications typically require meeting specific educational and experience standards and passing an examination. While not always mandatory, they can signal a level of professional competence and commitment, potentially improving job prospects in certain applied fields.

Career Progression in Anthropology

A career in anthropology can follow diverse trajectories, spanning academia, government, non-profits, and the private sector. Progression often depends on education level, specialization, experience, and networking.

Entry-Level Positions: Academia vs. Applied Anthropology

With a bachelor's degree, entry-level opportunities might include research assistant roles, museum technician positions, or fieldwork assistance in archaeology (often through Cultural Resource Management firms). Some graduates find roles in community outreach, social services, or entry-level positions in NGOs or government that value cross-cultural skills.

A master's degree opens more doors, particularly in applied settings. Graduates may work as researchers or analysts for government agencies, non-profits, or consulting firms. Positions in museum curation, cultural resource management, or program coordination are common. Some MA holders find teaching positions at community colleges.

Entry into academia almost always requires a PhD. Initial positions are often postdoctoral fellowships or assistant professorships, which are highly competitive. These roles involve teaching, research, publishing, and service to the university. Applied anthropology roles at the PhD level might involve leading research teams, high-level consulting, or senior policy advising.

Mid-Career Specialization Paths

As anthropologists gain experience, they often develop deeper specializations. Academics typically focus their research and teaching on specific theoretical areas, geographic regions, or subfield specializations (e.g., medical anthropology, environmental anthropology, political anthropology).

Applied anthropologists might specialize in areas like user experience (UX) research, market research, organizational development, international development consulting, public health program evaluation, or forensic analysis. Specialization allows for the development of deeper expertise and often leads to greater responsibility and influence.

Mid-career progression can involve moving into management roles, leading larger research projects, securing significant grant funding, or establishing oneself as a recognized expert in a particular niche. Networking, continued learning, and publishing or presenting findings remain important throughout the career.

Explore potential areas of specialization through these courses.

Leadership Roles in Cultural Resource Management

Cultural Resource Management (CRM) is a major employment sector for archaeologists and some cultural anthropologists, particularly in the US. CRM involves identifying, evaluating, and managing cultural resources (like archaeological sites or historic buildings) impacted by development projects, as mandated by federal and state laws.

Entry-level CRM roles often involve fieldwork (surveying, excavation). With experience and often an advanced degree (MA or PhD), individuals can progress to supervisory roles, project management, and senior leadership positions within CRM firms or government agencies (like the National Park Service or State Historic Preservation Offices).

Leadership roles in CRM require strong project management skills, knowledge of relevant legislation, expertise in archaeological or anthropological methods, report writing abilities, and the capacity to manage teams and budgets. These positions involve significant responsibility for preserving cultural heritage.

Transition Opportunities to Policy or NGO Work

The skills and perspectives gained through anthropological training are highly relevant to policy analysis and work within non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Anthropologists' understanding of cultural contexts, social systems, and human behavior enables them to contribute unique insights to policy formulation, program design, and advocacy efforts.

Transitioning into these fields may involve roles as policy analysts, program officers, researchers, evaluators, or advocates. Anthropologists often work on issues related to international development, human rights, public health, environmental policy, migration, and social justice. Their ability to conduct qualitative research and understand diverse perspectives is particularly valuable.

Networking within policy circles or the NGO sector, gaining experience through internships or volunteer work, and sometimes pursuing additional training (e.g., a Master of Public Policy or Public Health) can facilitate this transition. Strong communication skills, particularly the ability to translate complex research into actionable recommendations, are essential.

These courses explore policy, social justice, and related areas relevant to NGO or policy work.

Ethical Challenges in Anthropological Practice

The intimate nature of anthropological research, often involving deep engagement with communities and sensitive topics, presents unique ethical challenges. Navigating these requires ongoing reflection, adherence to ethical principles, and a commitment to minimizing harm.

Cultural Appropriation Concerns

Anthropologists study and represent cultures, which inherently raises concerns about cultural appropriation – the adoption or use of elements of a minority culture by members of the dominant culture, often without understanding or respect. Researchers must be careful not to exoticize, stereotype, or misrepresent the cultures they study.

This involves critically examining who benefits from the research and how cultural knowledge is shared and used. It requires collaborating with community members, ensuring fair representation, and potentially involving them in the research process and the dissemination of findings. Giving credit where it is due and respecting intellectual property rights are crucial.

The history of anthropology includes instances where researchers benefited disproportionately from the knowledge of the communities they studied. Contemporary ethical practice strives to move towards more equitable and collaborative relationships, acknowledging the potential for harm inherent in representing other cultures.

Working with Vulnerable Populations

Anthropological research often involves working with populations who may be considered vulnerable due to factors like poverty, political marginalization, displacement, illness, or age. Researching sensitive topics like trauma, violence, or discrimination also requires particular ethical care.

Ethical obligations are heightened when working with vulnerable groups. Researchers must take extra precautions to ensure participants are not exploited, coerced, or put at further risk. This includes careful consideration of informed consent procedures, ensuring genuine understanding and voluntariness, and robust measures to protect confidentiality and anonymity.

Researchers must be sensitive to potential power imbalances and avoid causing additional distress or harm. Providing appropriate support or referrals if participants become distressed, and considering how research findings might impact the community, are important responsibilities. The principle of "do no harm" (non-maleficence) is paramount.

Decolonization of Anthropological Methods

Anthropology's historical roots are intertwined with colonialism, and the discipline continues to grapple with this legacy. The movement to decolonize anthropology calls for critically examining and challenging colonial-era power structures, assumptions, and methodologies that may persist within the field.

This involves questioning traditional research relationships where the researcher (often from a dominant culture) holds primary authority over knowledge production about the researched community. Decolonizing approaches emphasize collaboration, co-creation of knowledge, centering Indigenous or local perspectives, and ensuring research benefits the communities involved.

It also means challenging Eurocentric theoretical frameworks and promoting diverse ways of knowing. This ongoing process requires anthropologists to be self-reflexive about their own positionality and privilege, engage critically with the discipline's history, and actively work towards more equitable and just research practices.

These books provide critical historical context relevant to discussions of colonialism and power dynamics.

Case Studies of Ethical Dilemmas

Ethical guidelines provide principles, but real-world fieldwork often presents complex dilemmas with no easy answers. Case studies of ethical challenges faced by anthropologists offer valuable learning opportunities, illustrating the practical difficulties of applying ethical principles in specific contexts.

Dilemmas might involve conflicting obligations (e.g., protecting confidentiality vs. reporting illegal activities), navigating internal community conflicts, dealing with requests for advocacy or intervention, or managing unexpected consequences of the research. For instance, how should a researcher respond if they witness harmful practices? What happens if research findings could negatively impact the community studied?

Analyzing case studies helps researchers develop ethical reasoning skills and prepare for potential challenges. Professional associations often publish case studies and discussions of ethical dilemmas, fostering ongoing dialogue within the discipline about responsible conduct. Transparency about ethical challenges encountered during research is also increasingly encouraged.

Global Opportunities for Anthropologists

The cross-cultural expertise and global perspective inherent in anthropology open doors to numerous international career opportunities. Anthropologists are well-suited for roles that require navigating diverse cultural landscapes and understanding global processes.

UNESCO and International Cultural Preservation

Organizations like UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) work to protect and promote cultural heritage worldwide. Anthropologists, particularly archaeologists and cultural anthropologists, contribute significantly to these efforts.

Their work might involve identifying and documenting tangible cultural heritage (like archaeological sites) or intangible cultural heritage (like traditional practices, languages, or performing arts). They may assist in developing conservation plans, working with local communities to safeguard their heritage, or advising on policies related to cultural preservation.

Expertise in cultural contexts, community engagement, and research methodologies makes anthropologists valuable assets in international organizations dedicated to cultural understanding and preservation. Related opportunities exist within national heritage agencies, museums with international collections, and NGOs focused on cultural survival.

Cross-Cultural Consulting in Global Business

As businesses operate increasingly across international borders, the need for cross-cultural understanding has grown. Anthropologists are employed as consultants to help companies navigate cultural differences in global markets, international team management, and product localization.

They might advise on culturally appropriate marketing strategies, help facilitate communication within multinational teams, conduct ethnographic research to understand consumer behavior in different countries, or provide training on cultural competency for employees working internationally.

Their ability to analyze cultural nuances, understand diverse perspectives, and identify potential misunderstandings is highly valued in global business contexts. This applied field, sometimes called business anthropology, helps organizations operate more effectively and ethically in a globalized world.

These courses address cross-cultural management and global perspectives relevant to consulting.

Language Proficiency Requirements

For anthropologists conducting fieldwork or working internationally, proficiency in languages other than their native tongue is often essential, or at least highly advantageous. Learning the local language is crucial for effective communication, building rapport, and gaining deeper cultural insights during ethnographic research.

Many graduate programs require demonstrating proficiency in one or more foreign languages relevant to the student's research area. In international jobs, fluency in relevant languages (e.g., official UN languages or languages spoken in specific regions of focus) can be a significant asset or even a requirement.

Even basic language skills can facilitate interactions and show respect for local cultures. Continuous language learning is often part of an anthropologist's professional development, particularly for those working in diverse linguistic environments. You can find language courses through resources like OpenCourser's language section.

These courses focus on specific languages and cultures, highlighting the importance of linguistic diversity.

Cultural Adaptation Strategies

Working effectively across cultures requires more than just language skills; it demands strong cultural adaptation abilities. Anthropologists, through their training and fieldwork experiences, develop heightened cultural sensitivity and adaptability.

This involves recognizing and respecting cultural differences in communication styles, social norms, values, and work practices. It means being open-minded, flexible, and able to navigate ambiguity and potential misunderstandings. Self-awareness of one's own cultural biases is also critical.

These skills are essential not only for conducting research but also for collaborating effectively in international teams, managing diverse workforces, implementing development projects, or providing culturally competent services. Anthropologists often excel at bridging cultural divides and fostering mutual understanding in complex global settings.

These courses provide insights into different cultures and the dynamics of cross-cultural interaction.

Challenges Facing Modern Anthropologists

Despite its unique insights, the field of anthropology faces several contemporary challenges, impacting research, employment, and public perception. Understanding these challenges is crucial for anyone considering a career in the discipline.

Funding Landscape for Anthropological Research

Securing funding for anthropological research, particularly long-term ethnographic fieldwork or archaeological excavation, can be challenging. Academic research often relies on grants from government agencies (like the National Science Foundation or National Institutes of Health in the US), private foundations, and universities.

Competition for these grants is often intense, and funding levels can fluctuate based on governmental budgets and institutional priorities. This uncertainty can impact the feasibility of research projects and create job insecurity, especially for early-career academics. Applied anthropologists may face different funding dynamics, depending on their clients or employing organizations.

Developing strong grant-writing skills, diversifying funding sources, and collaborating on interdisciplinary projects are strategies anthropologists use to navigate the funding landscape. However, limited resources remain a persistent challenge for the discipline.

Technological Disruption of Traditional Methods

Advances in technology are transforming anthropological research, presenting both opportunities and challenges. Digital technologies facilitate new forms of data collection (e.g., online ethnography, analysis of large datasets) and dissemination. However, they also raise new ethical questions regarding privacy, data security, and digital divides.

The increasing availability of genetic data, remote sensing technologies (like LiDAR for archaeology), and computational analysis tools requires anthropologists to develop new technical skills. There's ongoing debate about how to integrate these technologies effectively while maintaining the strengths of traditional qualitative methods like ethnography.

Keeping pace with technological change and adapting methodologies accordingly is an ongoing challenge. Failure to engage with new technologies could risk marginalizing anthropological perspectives in fields increasingly dominated by quantitative or computational approaches.

Public Perception and Relevance Debates

Anthropology sometimes struggles with public perception, occasionally being viewed as an esoteric or purely academic pursuit with limited practical relevance. Stereotypes based on outdated portrayals of anthropologists studying "exotic" cultures can persist.

Communicating the value and applicability of anthropological insights to broader audiences and potential employers remains a challenge. Demonstrating how anthropological perspectives contribute to solving real-world problems – in business, health, policy, technology design, and social justice – is crucial for the discipline's continued relevance.

Internal debates also exist regarding the discipline's direction, the balance between theoretical and applied work, and its role in addressing pressing global issues. Effectively articulating anthropology's unique contributions and engaging proactively with public discourse are ongoing tasks for the field.

Climate Change Impacts on Fieldwork

Climate change poses significant challenges to anthropological research, particularly fieldwork. Rising sea levels, extreme weather events, desertification, and melting ice threaten archaeological sites and the environments where communities live.

Environmental changes can disrupt traditional lifeways, force migration, and alter the cultural landscapes anthropologists study. Access to field sites may become more difficult or dangerous. Furthermore, ethical considerations arise regarding researching communities facing climate-related crises, ensuring research does not add further burden.

Anthropologists are increasingly studying the human dimensions of climate change – how communities perceive, adapt to, and are impacted by environmental shifts. However, climate change also directly impacts the feasibility and safety of conducting research in many parts of the world, adding another layer of complexity to fieldwork.

Emerging Trends in Anthropological Practice

Anthropology is a dynamic field, constantly adapting its methods and focus to understand the complexities of the contemporary world. Several emerging trends highlight the discipline's evolution and its engagement with new technologies and interdisciplinary approaches.

Digital Ethnography and Virtual Fieldwork

As human interaction increasingly moves online, anthropologists are developing methods for studying digital communities and cultures. Digital ethnography involves adapting traditional ethnographic techniques – like participant observation and interviewing – to online environments such as social media platforms, gaming worlds, and online forums.

This allows researchers to explore online identities, social dynamics, communication patterns, and the cultural meanings created in virtual spaces. It presents unique methodological challenges (e.g., defining the "field," establishing rapport) and ethical considerations (e.g., privacy, consent in public online spaces).

Virtual fieldwork and digital methods expand the scope of anthropological inquiry, enabling the study of phenomena that transcend geographical boundaries and offering insights into how technology shapes human experience. This area intersects with fields like media studies and communication studies.

Bio-cultural Synthesis Approaches

Breaking down traditional divides between biological and cultural anthropology, bio-cultural approaches seek to integrate biological and cultural perspectives to understand human phenomena. This recognizes that human biology and culture are deeply intertwined and mutually influential.

Bio-cultural research might explore how cultural practices affect human health and biology (e.g., diet and disease), how biological factors influence social behavior, or how environmental changes impact both human biology and culture. It often involves collaboration between biological and cultural anthropologists, employing mixed methods.

This trend reflects a move towards more holistic and integrated understandings of human diversity and adaptation, drawing on insights from genetics, epigenetics, physiology, cultural analysis, and evolutionary theory.

Corporate Anthropology in UX Research

A significant growth area for applied anthropology is within the tech industry, particularly in User Experience (UX) research. Anthropologists bring valuable skills to UX, using ethnographic methods to understand how people interact with technology in their everyday lives.

They conduct qualitative research – interviews, observations, usability studies – to uncover user needs, motivations, and pain points. This deep cultural understanding helps design teams create products and services that are more intuitive, useful, and culturally appropriate. Anthropological perspectives emphasize context, holistic understanding, and empathy for the user.

This field, often called business anthropology or design anthropology, demonstrates the practical application of anthropological methods and theories in industry, contributing to product development, strategy, and innovation.

Forensic Anthropology Advancements

Forensic anthropology, the application of anthropological methods (primarily from biological anthropology and archaeology) to legal contexts, continues to advance. Forensic anthropologists assist law enforcement and medical examiners in identifying human remains and determining cause of death, particularly in cases involving decomposed or skeletonized bodies.

Advancements include refined techniques for estimating age, sex, ancestry, and stature from skeletal remains, as well as new methods for analyzing trauma and identifying individuals through skeletal features or DNA. Technology, such as 3D imaging and isotopic analysis, plays an increasing role.

The field requires rigorous training in human osteology, archaeology, and medico-legal procedures. Growing demand exists within government agencies and medical examiner offices, though it remains a highly specialized and competitive field.

Frequently Asked Questions

Navigating the path to becoming an anthropologist often raises common questions. Here are answers to some frequently asked questions about the field and career prospects.

Can anthropologists work outside academia?

Absolutely. While academia is a traditional path, a significant and growing number of anthropologists work outside universities. They are employed in government agencies (federal, state, local), non-profit organizations (international development, human rights, community health), museums, cultural resource management firms, and private industry (market research, user experience research, consulting).

The skills developed in anthropology – cross-cultural understanding, qualitative research methods, critical analysis, communication – are valuable in many sectors. An MA degree often suffices for applied roles, though PhDs also work outside academia, sometimes in high-level research or leadership positions. The key is often translating anthropological skills into language understood by non-academic employers.

What's the job market outlook for anthropology PhDs?

The academic job market for anthropology PhDs is highly competitive. The number of PhD graduates often exceeds the number of available tenure-track faculty positions. Many PhDs pursue postdoctoral fellowships or adjunct teaching positions initially, facing uncertainty in securing permanent academic employment.

However, PhD holders are increasingly finding rewarding careers outside academia. Their advanced research skills, analytical abilities, and deep expertise are valued in research institutes, government, NGOs, and the private sector, particularly in roles requiring complex problem-solving and qualitative research leadership. Networking and gaining experience relevant to non-academic settings during graduate school can improve prospects.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), employment for anthropologists and archeologists overall is projected to grow about 4% from 2023 to 2033, which is about average for all occupations. However, much of this growth may be in applied fields, and competition for positions, especially academic ones, remains strong.

How competitive are museum curator positions?

Museum curator positions are generally very competitive. Curators are responsible for overseeing collections, conducting research, developing exhibits, and engaging with the public. Most curator positions require an advanced degree (MA or PhD) in anthropology, archaeology, history, art history, or a related field, along with specialized knowledge and museum experience.

Experience gained through internships, volunteering, or entry-level museum roles (like collections assistant or museum technician) is often crucial for securing a curatorial position. The number of available positions is limited compared to the number of qualified applicants. Networking within the museum field and demonstrating strong research, communication, and organizational skills are important.

The BLS projects job growth for curators (grouped with archivists and museum workers) to be around 9% between 2023 and 2033, faster than average, but starting from a relatively small base means competition will likely remain high.

Do anthropologists need foreign language skills?

Foreign language skills are highly valuable, and often essential, for anthropologists, particularly those conducting ethnographic fieldwork in non-English speaking communities or working internationally. Proficiency allows for direct communication, deeper understanding of cultural nuances, and building better rapport with research participants.

Many PhD programs require candidates to demonstrate proficiency in at least one foreign language relevant to their research area. While not always a strict requirement for every applied anthropology job, language skills significantly enhance competitiveness for roles involving international work, cross-cultural communication, or research with specific linguistic groups.

Even if fluent command isn't achieved, making an effort to learn basic communication in the local language during fieldwork is considered crucial for ethical and effective research.

Is fieldwork always required?

Fieldwork is a central component of anthropological training and practice, especially for cultural anthropologists, linguistic anthropologists, and archaeologists. It's the primary way anthropologists gather original data and gain deep contextual understanding. For a PhD involving ethnographic or archaeological research, substantial fieldwork is typically mandatory.

However, not all anthropologists spend their entire careers conducting traditional, long-term fieldwork. Some may focus more on analyzing existing data, theoretical work, teaching, museum collections management, or applied roles that involve shorter-term research projects or consultations. Digital anthropology also involves different forms of "fieldwork" online.

While direct fieldwork experience is highly valued and foundational to the discipline, the specific requirements and nature of fieldwork can vary depending on the subfield, research focus, and career path.

How does cultural anthropology differ from sociology?

Cultural anthropology and sociology are closely related social sciences that study human societies and behavior, and they often overlap in topics and theories. However, they have traditionally differed in their focus and methodologies.

Historically, anthropology focused more on non-Western, small-scale societies and employed qualitative, long-term ethnographic fieldwork (participant observation) as its primary method. Sociology tended to focus more on Western, large-scale, industrial societies and often utilized quantitative methods like surveys and statistical analysis, alongside qualitative approaches.

Today, these distinctions have blurred considerably. Anthropologists study all types of societies, including complex urban ones, and sociologists increasingly use qualitative methods. However, anthropology often retains a stronger emphasis on cultural relativism, deep contextual understanding through fieldwork, cross-cultural comparison, and a holistic perspective incorporating biological and linguistic dimensions.

Salary Expectations

Salaries for anthropologists vary significantly based on factors like education level, experience, sector of employment (academia, government, private industry, non-profit), geographic location, and specific role or specialization.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the median annual wage for anthropologists and archeologists was $63,800 in May 2023. The lowest 10 percent earned less than $43,770, and the highest 10 percent earned more than $102,150. Other sources like Salary.com report a slightly higher average around $71,353 as of April 2025, with typical ranges between $66,239 and $77,876. ZipRecruiter notes a lower average hourly wage around $18.18, but also points out that salaries for specific roles like Cultural Anthropology average around $60,710 annually, with potential for advancement based on skill and location.

Generally, positions requiring a PhD, particularly in academia or senior government/consulting roles, tend to command higher salaries. Federal government positions often offer competitive salaries. Entry-level positions, especially those requiring only a bachelor's degree, will typically be at the lower end of the salary range.

Is Anthropology Right for You?

Choosing a career in anthropology requires careful consideration. It's a field driven by deep curiosity about humanity, cultural diversity, and the complexities of social life. Successful anthropologists are typically adaptable, observant, empathetic, analytical, and skilled communicators.

If you are fascinated by different cultures, enjoy in-depth research, possess strong critical thinking skills, and are comfortable navigating ambiguity and diverse perspectives, anthropology might be a good fit. The path often requires significant educational investment and persistence, particularly for academic careers. The job market can be competitive, demanding flexibility and sometimes a willingness to work in non-traditional settings.

For those considering a career change, anthropology can offer a deeply rewarding way to apply life experience and intellectual curiosity. The transition might require further education or finding ways to leverage existing skills within an anthropological framework. Be prepared for the challenges, but know that the unique perspective gained through anthropology is valuable in many domains. Exploring introductory courses and readings, like those available through OpenCourser, can help you gauge your interest and aptitude.

Ultimately, a career as an anthropologist offers a unique way to engage with the world, contribute to understanding human diversity, and potentially address pressing social issues. It demands intellectual rigor and adaptability but provides unparalleled insights into the human condition.