Surveyor

A Comprehensive Guide to a Career as a Surveyor

Surveying is the science, art, and profession of determining the precise three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them, commonly practiced by surveyors. These points are usually on the surface of the Earth, and they are often used to establish maps and boundaries for ownership, locations like building corners or the surface location of subsurface features, or other purposes required by government or civil law, such as property sales. Surveying has been an essential element in the development of the human environment since the beginning of recorded history.

Working as a surveyor involves a unique blend of fieldwork and office work. You might spend part of your week outdoors, navigating diverse terrains and using sophisticated equipment to gather data. The rest of the week could involve analyzing this data, creating maps, and preparing reports. This career offers the satisfaction of contributing directly to infrastructure development, land management, and ensuring the accuracy of property boundaries, playing a crucial role in how we shape and understand our world.

What Does a Surveyor Do?

Understanding the day-to-day life of a surveyor helps paint a clearer picture of this dynamic profession. It's a role that requires precision, analytical skills, and adaptability, often blending outdoor exploration with indoor data processing.

Daily Responsibilities and Core Tasks

A surveyor's primary duty is to make precise measurements of land features, boundaries, and elevations. This involves visiting sites, using specialized equipment like total stations, GPS receivers, and levels to collect data. They meticulously record their findings, ensuring accuracy down to the smallest detail.

Back in the office, surveyors process this field data. They use software to analyze measurements, calculate dimensions, and create detailed maps, plats, and reports. These documents serve as legal records for property boundaries, guides for construction projects, or data for geographic information systems (GIS).

Surveyors also research historical records, legal documents, and previous surveys to verify property lines and gather context for their current work. They must interpret complex information and reconcile any discrepancies found between records and field observations.

Specializations within Surveying

The field of surveying is broad, allowing professionals to specialize in areas that match their interests. Geodetic surveyors focus on measuring large areas of the Earth's surface, considering its curvature and gravitational field, often contributing to large-scale mapping and satellite positioning systems.

Hydrographic surveyors specialize in mapping underwater features, measuring depths, and charting coastlines and seabeds. Their work is vital for navigation, offshore construction, and resource management.

Construction surveyors, also known as site surveyors, work closely with building projects. They set out reference points and markers to guide construction, ensuring buildings, roads, and other structures are built according to design plans. Other specializations include boundary surveying (determining legal property lines), topographic surveying (mapping surface features), and mining surveying.

These books offer a foundational understanding of surveying principles and practices, covering both theoretical knowledge and practical applications.

Collaboration and Communication

Surveyors rarely work in isolation. They collaborate extensively with engineers, architects, urban planners, construction managers, lawyers, and government officials. Clear communication is crucial for conveying survey findings, explaining technical details, and ensuring projects proceed accurately.

They provide essential data that informs design decisions, resolves boundary disputes, and ensures compliance with regulations. Strong interpersonal skills are needed to manage field crews, interact with clients, and present findings in reports or meetings.

The ability to translate complex spatial data into understandable formats for diverse audiences is a key part of the role. Whether discussing site constraints with an architect or presenting boundary evidence in a legal setting, effective communication underpins a surveyor's success.

Formal Education Pathways

Embarking on a surveying career typically involves specific educational steps. Understanding these pathways is crucial for aspiring surveyors, whether they are finishing high school, currently in university, or considering a career change.

Degree Requirements: Associate vs. Bachelor's

A bachelor's degree is generally the standard entry point for becoming a licensed surveyor. Programs in surveying, geomatics, or civil engineering with a surveying emphasis provide the necessary theoretical knowledge and practical skills. Curricula often cover mathematics (especially trigonometry and geometry), physics, mapping, photogrammetry, geodesy, property law, and computer-aided design (CAD).

Some states may allow individuals with an associate's degree in surveying technology to begin their careers, often as survey technicians or assistants working under a licensed surveyor. While an associate's degree can provide a solid foundation and entry into the field, pursuing a bachelor's degree is often necessary for advancement to full licensure and independent practice.

Accreditation is important. Many state licensing boards require graduation from a program accredited by ABET (Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology). Choosing an accredited program ensures the curriculum meets recognized professional standards.

These courses provide a glimpse into the mathematical foundations essential for surveying work.

Licensing and Examinations

Becoming a Professional Surveyor (PS) or Professional Land Surveyor (PLS) requires licensure in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. While requirements vary by state, the process generally involves education, experience, and examinations.

Most candidates must first pass the Fundamentals of Surveying (FS) exam. This exam, typically taken after completing or nearing completion of a relevant degree program, tests knowledge of basic surveying principles. Passing the FS exam often grants the title of Surveyor Intern (SI) or Surveyor-in-Training (SIT).

After gaining several years (usually four) of progressive work experience under the supervision of a licensed surveyor, candidates are eligible to take the Principles and Practice of Surveying (PS) exam. This exam assesses competency in applying surveying principles to real-world situations. Many states also require a third exam focusing on state-specific laws and regulations related to surveying practice. Information on specific state requirements can often be found on the websites of individual state licensing boards, accessible via the National Council of Examiners for Engineering and Surveying (NCEES) website.

Advanced Study and Research

For those interested in pushing the boundaries of surveying science and technology, pursuing a Master's or Ph.D. in geomatics, geospatial science, or a related field offers opportunities for advanced research and specialization. Graduate studies can lead to careers in academia, research institutions, or specialized roles within government agencies or private firms.

Research areas might include developing new remote sensing techniques, improving GPS/GNSS accuracy, advancing LiDAR data processing, refining GIS applications, or exploring the theoretical underpinnings of geodesy. Advanced degrees can open doors to leadership positions and roles focused on innovation within the surveying profession.

Online and Independent Learning

While formal education and licensure are cornerstones of the surveying profession, online learning and self-directed study offer valuable pathways to build foundational knowledge, supplement traditional education, and enhance practical skills. This is particularly relevant for those exploring the field, career changers needing to bridge knowledge gaps, or professionals seeking continuous development.

Building Foundational Knowledge Online

Can you learn surveying entirely online? While achieving full licensure requires accredited degrees and supervised experience, online courses are excellent resources for mastering fundamental concepts. Subjects like mathematics (algebra, geometry, trigonometry), physics, introductory GIS, and basic CAD principles are widely available through online platforms.

These courses allow learners to study at their own pace and can provide a solid theoretical base before committing to a formal degree program. They can also help individuals assess their aptitude and interest in the technical aspects of surveying. Exploring introductory modules can be a low-risk way to dip your toes into the field.

OpenCourser makes it simple to find relevant math courses or explore topics in Engineering and Geography. Using the "Save to List" feature helps organize potential learning resources for future review.

These online courses cover essential mathematical and geographical concepts relevant to surveying.

Supplementing Formal Education and Skills

For students already enrolled in surveying or related degree programs, online courses can supplement their curriculum. They might offer deeper dives into specific software (AutoCAD Civil 3D, ArcGIS), specialized techniques (remote sensing, photogrammetry), or emerging technologies (drone operation, LiDAR processing).

Professionals can use online learning to stay current with technological advancements, fulfill continuing education requirements for license renewal, or acquire new skills for career advancement. Courses focusing on specific equipment, data analysis methods, or project management can enhance expertise and marketability.

Platforms like OpenCourser aggregate offerings from various providers, allowing learners to compare syllabi, read reviews, and find courses tailored to their specific needs. The OpenCourser Learner's Guide provides valuable tips on structuring self-study and integrating online learning effectively.

These courses offer practical skills in GIS, CAD, and data analysis, which are highly valuable for surveyors.

Building a Portfolio Through Projects

Theoretical knowledge is best solidified through practical application. Online learning can be paired with hands-on projects to build a portfolio, demonstrating skills to potential employers or academic programs. Open-source GIS software (like QGIS) and publicly available datasets allow learners to practice mapping and spatial analysis techniques.

Contributing to open-source mapping projects (like OpenStreetMap) or undertaking personal projects, such as mapping local parks or analyzing publicly available geospatial data, provides practical experience. Documenting these projects, outlining the methods used and results achieved, creates tangible proof of competence.

While self-study and online projects cannot replace the supervised field experience required for licensure, they significantly strengthen a candidate's profile and demonstrate initiative, technical aptitude, and a passion for the field. It shows a commitment to learning beyond formal requirements.

These courses provide hands-on experience with spatial data analysis and mapping software.

Surveyor Career Progression Path

Understanding the typical career trajectory for a surveyor can help aspiring professionals set realistic goals and plan their development. The path often involves moving from entry-level support roles to licensed professional status and potentially into management or specialized positions.

Entry-Level Roles

Most careers in surveying begin in entry-level positions, often while pursuing or shortly after completing formal education. Common starting roles include Field Assistant, Survey Technician, or Instrument Operator. In these roles, individuals work under the direct supervision of experienced surveyors.

Responsibilities typically involve assisting with fieldwork: carrying equipment, setting up instruments, clearing lines of sight, taking basic measurements, and recording notes. Office tasks might include data entry, basic drafting using CAD software, and organizing survey records. These roles provide invaluable hands-on experience with equipment, field procedures, and data collection processes.

The duration spent in entry-level roles varies but often aligns with the experience requirements for licensure, typically around four years. This period is crucial for learning the practical aspects of the profession and building a foundation for more complex tasks.

Mid-Career: Licensure and Project Management

After meeting the education, experience, and examination requirements, surveyors can achieve licensure as a Professional Surveyor (PS) or Professional Land Surveyor (PLS). This milestone signifies the competence to practice independently and take legal responsibility for survey work.

Licensed surveyors often take on greater responsibilities, managing field crews, overseeing entire survey projects, performing complex calculations and analyses, interpreting legal descriptions, and certifying survey maps and documents. They interact directly with clients, engineers, and attorneys, providing expert opinions and ensuring project accuracy.

With experience, licensed surveyors may move into project management roles. This involves planning and coordinating survey projects, managing budgets and schedules, supervising teams, ensuring quality control, and handling client relations. Strong organizational and leadership skills become increasingly important at this stage.

Advanced Career Paths

Experienced surveyors have several avenues for career advancement. Some choose to specialize further in technical areas like geodesy, photogrammetry, or hydrography, becoming sought-after experts in their niche.

Others move into senior management or leadership positions within surveying firms or government agencies. Entrepreneurship is another common path, with many licensed surveyors establishing their own consulting firms, offering specialized services to clients.

Highly experienced surveyors may also serve as expert witnesses in legal cases involving boundary disputes, land use, or construction issues. Their deep knowledge of surveying principles and practices allows them to provide authoritative testimony in court proceedings. Continuous learning and adaptation to new technologies remain crucial throughout a surveyor's career.

Essential Skills for Surveyors

Success in surveying demands a blend of technical expertise, legal understanding, and crucial soft skills. Mastering these competencies is vital for accuracy, efficiency, and effective collaboration throughout a surveyor's career.

Technical Proficiency

A strong foundation in mathematics, particularly trigonometry, geometry, and algebra, is fundamental. Surveyors constantly use mathematical principles to calculate distances, angles, areas, and volumes. Precision in calculations is paramount, as errors can have significant legal and financial consequences.

Proficiency with surveying equipment, both traditional (like levels and theodolites) and modern (like total stations, GPS/GNSS receivers, laser scanners, and drones), is essential. This includes understanding how the instruments work, proper calibration, operation techniques, and potential sources of error.

Competence in relevant software is equally important. Surveyors regularly use Computer-Aided Design (CAD) software, such as AutoCAD Civil 3D, to draft maps and plans, and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) software for spatial data analysis and management. Familiarity with data processing and adjustment software is also necessary.

These online courses focus on building core technical skills in CAD and GIS relevant to surveying.

Legal and Regulatory Knowledge

Surveyors operate within a complex legal framework. A thorough understanding of property laws, boundary principles, land registration systems, and zoning regulations is critical. They must be able to interpret legal descriptions found in deeds and other documents.

Knowledge of local, state, and federal regulations governing land development and construction is also necessary. Surveyors ensure that projects comply with these rules and that survey documents meet legal standards for recording and validity.

This legal acumen is especially vital in boundary surveying, where surveyors often act as impartial investigators, gathering and analyzing evidence to retrace original property lines according to established legal principles. Their findings can have significant implications in property disputes.

Soft Skills and Professional Attributes

Attention to detail is perhaps the most crucial soft skill. Surveying demands meticulous accuracy in measurement, calculation, and documentation. Small errors can lead to large problems, so a systematic and precise approach is essential.

Strong problem-solving skills are needed to address challenges encountered in the field or office. This might involve reconciling conflicting data, finding ways to survey difficult terrain, or resolving boundary ambiguities based on historical evidence and legal precedent.

Effective communication skills, both written and verbal, are vital for interacting with clients, team members, and other professionals. Surveyors must clearly explain technical concepts, present findings, write comprehensive reports, and provide clear instructions. Physical stamina is also important for fieldwork, which often involves walking long distances over uneven terrain while carrying equipment, sometimes in adverse weather conditions.

Tools and Technologies

The field of surveying has evolved significantly, integrating sophisticated technology alongside traditional methods. Proficiency with a range of tools and software is essential for modern surveyors to perform their work accurately and efficiently.

Traditional Surveying Instruments

Despite technological advancements, foundational tools remain relevant. Theodolites are used to measure horizontal and vertical angles with high precision. Levels are employed to determine differences in elevation between points, crucial for establishing grades and contours.

Measuring tapes and chains, while less common for long distances today, are still used for shorter measurements or specific tasks. Compasses help determine direction, though they are often supplemented or replaced by more precise electronic methods.

Understanding the principles behind these traditional tools provides a strong foundation for comprehending how more complex modern instruments function. Basic navigation and measurement techniques remain valuable skills.

These courses cover fundamental navigation techniques relevant to traditional surveying practices.

Modern Equipment and Systems

Total stations, which combine an electronic theodolite with an electronic distance meter (EDM), are workhorses in modern surveying. They measure angles and distances simultaneously, recording data electronically for easy transfer to computers.

Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS), including the well-known Global Positioning System (GPS), allow surveyors to determine precise coordinates anywhere on Earth. Survey-grade GNSS receivers provide much higher accuracy than consumer devices.

Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) technology uses laser pulses to measure distances and create detailed 3D point clouds of surfaces and objects. LiDAR can be ground-based or mounted on aircraft or drones (UAVs). Drones themselves have become powerful surveying tools, used for aerial mapping (photogrammetry) and remote data collection, especially in large or inaccessible areas.

These courses explore the use of drones and related technologies in mapping and data collection.

Software and Data Processing

Software plays a critical role in modern surveying. CAD software, particularly industry standards like AutoCAD Civil 3D, is used for drafting survey plans, creating alignments, modeling surfaces, and generating construction drawings.

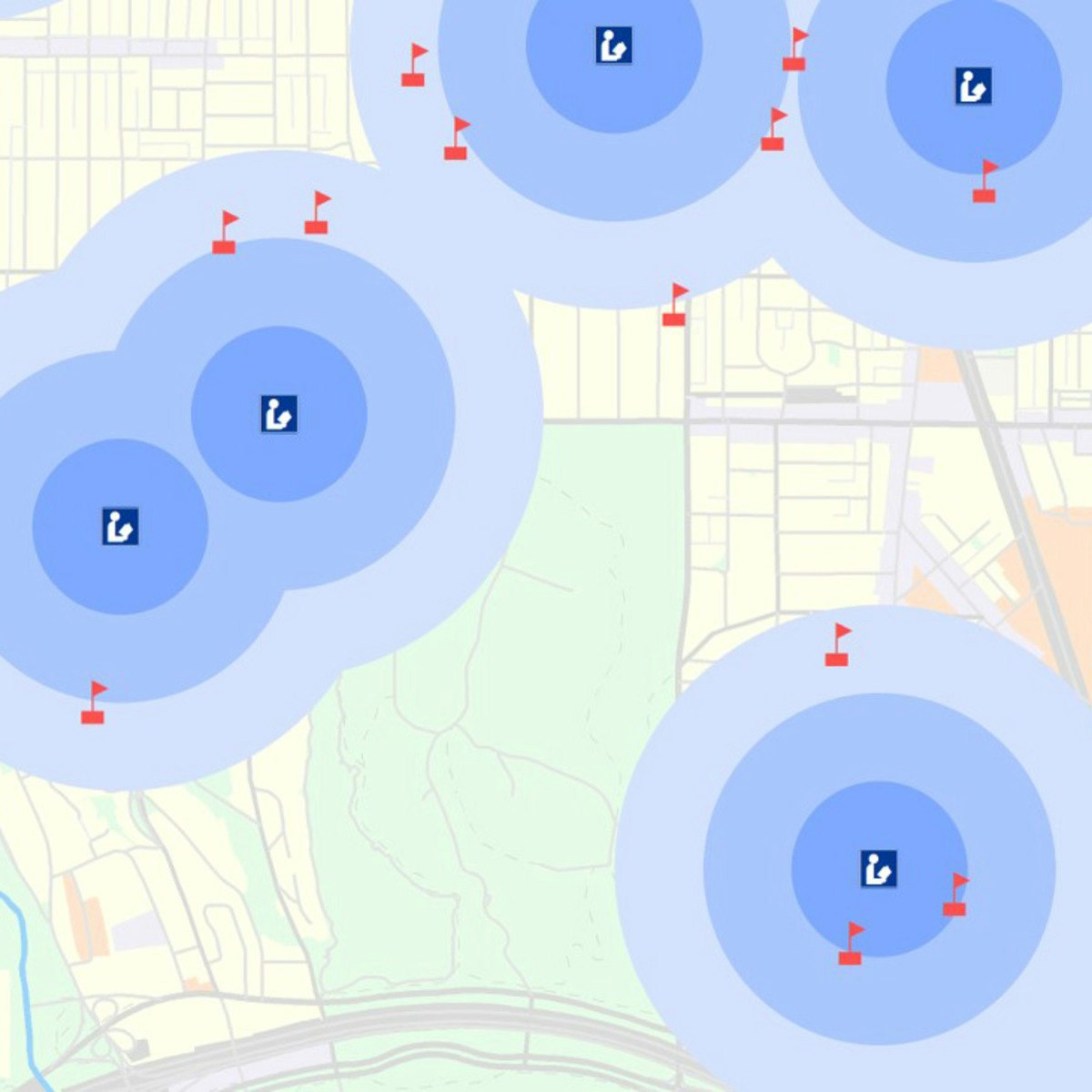

GIS software (e.g., ArcGIS, QGIS) is used to manage, analyze, and visualize geospatial data. Surveyors use GIS to integrate survey data with other datasets, perform spatial analysis, and create thematic maps.

Specialized software is also used for processing data from specific instruments, such as GNSS post-processing software to achieve higher accuracy, photogrammetry software to generate maps and models from drone imagery, and LiDAR processing software to analyze point cloud data. Proficiency in data management and analysis software is crucial for turning raw field measurements into meaningful deliverables.

These courses provide training in key software platforms used extensively in surveying and related fields.

Ethical and Legal Challenges

The practice of surveying carries significant ethical responsibilities and operates within a framework of legal requirements. Navigating these challenges requires professionalism, integrity, and a deep understanding of both technical principles and legal standards.

Boundary Dispute Resolution

One of the most common and challenging aspects of surveying, particularly boundary surveying, is dealing with property line disputes. Surveyors are often called upon to retrace historical boundaries based on ambiguous or conflicting deed descriptions and physical evidence.

Acting ethically in these situations means conducting impartial investigations, meticulously gathering and evaluating all available evidence (both documentary and physical), and applying established legal principles for boundary retracement. The surveyor's role is not to advocate for one party but to determine the most probable location of the boundary based on the evidence.

Presenting findings clearly and objectively is crucial. Surveyors may need to explain complex technical and legal reasoning to landowners, attorneys, or courts. Maintaining neutrality and professional integrity is paramount, even under pressure from clients or conflicting parties.

Professional Liability

Surveyors bear significant responsibility for the accuracy of their work. Errors in measurement, calculation, or interpretation can lead to costly construction mistakes, legal disputes, or financial losses for clients. This exposes surveyors to potential professional liability claims.

Maintaining high standards of care, adhering to established procedures, performing thorough quality checks, and keeping detailed records are essential risk management practices. Continuing education helps surveyors stay current with best practices and technological advancements, reducing the likelihood of errors.

Professional liability insurance (Errors & Omissions insurance) is typically carried by surveyors and surveying firms to protect against claims of negligence. Understanding contract law and clearly defining the scope of services in client agreements also helps manage liability risks.

Environmental and Societal Considerations

Surveying activities can intersect with environmental regulations and community interests. For example, surveys for development projects must consider potential impacts on wetlands, protected habitats, or archaeological sites. Surveyors may need to identify and map these sensitive areas.

Ethical practice involves respecting environmental regulations and contributing to sustainable development. This might include using low-impact field techniques or providing accurate data that helps planners minimize environmental disruption.

Surveyors also play a role in land administration systems that support secure land tenure and equitable access to resources. In some contexts, this involves navigating complex social dynamics and historical land claims, requiring cultural sensitivity and a commitment to fairness.

Future of Surveying

The surveying profession is continuously evolving, driven by technological innovation, changing societal needs, and global trends. Understanding these future directions is important for assessing the long-term viability and opportunities within the field.

Impact of AI and Automation

Artificial intelligence (AI) and automation are increasingly impacting data processing and analysis in surveying. AI algorithms can assist in feature extraction from LiDAR point clouds or satellite imagery, automate parts of the map creation process, and potentially identify patterns or anomalies in survey data.

Autonomous drones and robotic total stations can perform routine data collection tasks with less human intervention, increasing efficiency and safety, particularly in hazardous environments. According to MFS Engineering, these technologies enable surveyors to tackle complex projects with greater precision and insight.

While automation may change specific tasks, the need for skilled surveyors remains. Human judgment is still crucial for planning surveys, interpreting complex legal descriptions, evaluating evidence, resolving boundary issues, ensuring quality control, and providing professional certification. The focus may shift towards higher-level analysis, data integration, and project management, requiring surveyors to adapt and enhance their skill sets.

These courses touch upon the integration of AI and advanced technologies relevant to geospatial fields.

Climate Change and Infrastructure Needs

Climate change presents new challenges and opportunities for surveyors. Monitoring sea-level rise, coastal erosion, land subsidence, and glacial melt requires precise geospatial measurements over time. Surveyors play a key role in collecting data for climate modeling, adaptation planning, and disaster risk management.

Furthermore, significant investment in infrastructure renewal and development is anticipated globally. This includes upgrading aging transportation networks, building renewable energy facilities, and expanding digital communication infrastructure. All these projects rely heavily on accurate surveying and mapping services from planning through construction.

The International Federation of Surveyors (FIG), a UN-recognized NGO, highlights the role surveyors play in addressing global challenges like climate change and sustainable development, promoting professional practice and standards worldwide.

Global Opportunities and Evolving Skills

The demand for skilled surveyors exists worldwide, driven by urbanization, resource management, and infrastructure projects. While licensing is typically jurisdiction-specific, organizations like FIG facilitate international collaboration and knowledge sharing.

The surveyor of the future will likely need a broader skill set, integrating traditional surveying principles with expertise in GIS, remote sensing, data analytics, and potentially programming. Adaptability and a commitment to lifelong learning will be essential to keep pace with technological advancements and evolving industry demands.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, employment of surveyors is projected to grow 6 percent from 2023 to 2033, faster than the average for all occupations, indicating continued demand for these professionals.

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are answers to some common questions potential surveyors might have about the career path, prospects, and requirements.

What is the typical salary range for surveyors?

Salaries for surveyors vary based on experience, location, specialization, licensure, and employer type. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the median annual wage for surveyors was $68,540 in May 2023. The lowest 10 percent earned less than $41,430, while the highest 10 percent earned more than $109,660.

Other sources like Talent.com report an average salary closer to $87,973 per year in 2025, with entry-level positions starting around $70,000 and experienced professionals potentially exceeding $120,000. Salaries tend to be higher in regions with high demand and higher costs of living, and licensed surveyors generally earn more than unlicensed technicians.

Is automation a threat to surveying jobs?

Automation and AI are changing how surveyors work, but they are unlikely to eliminate the need for surveyors altogether. Technologies like drones and AI can automate routine data collection and processing tasks, increasing efficiency and allowing surveyors to focus on more complex aspects of the job.

However, professional judgment, legal interpretation, boundary resolution, quality assurance, and client interaction remain critical human elements. Surveyors who adapt to new technologies and develop skills in data analysis, GIS, and project management will likely find their roles evolving rather than disappearing. The demand for certified, legally responsible professionals remains strong.

Can a surveying license be used internationally?

Surveying licensure is typically specific to a particular country, state, or province. Requirements, regulations, and legal frameworks governing land ownership and surveying practices vary significantly across jurisdictions. Therefore, a license obtained in one country is generally not directly transferable to another.

However, some countries or regions may have mutual recognition agreements that streamline the process for licensed surveyors from specific jurisdictions to obtain licensure elsewhere. Organizations like the International Federation of Surveyors (FIG) work towards promoting international standards and facilitating collaboration, but direct license reciprocity is not widespread. Those wishing to practice internationally usually need to meet the specific licensing requirements of the target country.

What are the physical demands of the job?

Surveying often involves a significant amount of fieldwork, which can be physically demanding. Surveyors may need to walk long distances over rough or uneven terrain, sometimes in remote locations or adverse weather conditions. Carrying surveying equipment, which can be heavy, is also part of the job.

Fieldwork can require standing for long periods, bending, and navigating obstacles. Good physical stamina and the ability to work outdoors are important attributes. While office work involving data processing and map creation is also a major component, candidates should be prepared for the physical aspects of field data collection.

How can someone transition from Civil Engineering to Surveying?

Civil engineering and surveying are closely related fields, and transitioning between them is common. A civil engineering degree often includes coursework relevant to surveying, such as mathematics, physics, and basic measurement principles. Many surveyors work closely with civil engineers on construction and infrastructure projects.

To become a licensed surveyor, a civil engineer typically needs to fulfill the specific educational requirements (which might involve additional surveying-focused coursework), gain the required years of progressive surveying experience under a licensed surveyor, and pass the FS and PS exams (plus any state-specific exams). Some states offer specific pathways or considerations for licensed engineers seeking surveying licensure.

Are there opportunities for entrepreneurship in surveying?

Yes, entrepreneurship is a viable and common path for experienced, licensed surveyors. Many professionals choose to start their own surveying firms after gaining sufficient experience and building a network of contacts. Owning a firm allows for greater autonomy, specialization, and potentially higher earning potential.

Running a surveying business requires not only technical expertise but also business management skills, including marketing, finance, client relations, and personnel management. Starting small, perhaps focusing on a specific niche like boundary surveys or construction staking, is a common approach. The demand for surveying services provides a solid foundation for entrepreneurial ventures in this field.

A career in surveying offers a unique mix of outdoor work, technical challenges, and contributions to societal development. It requires precision, analytical thinking, and continuous learning. Whether mapping vast landscapes or defining property lines, surveyors play a vital role in shaping our understanding and use of the physical world. With strong job prospects and diverse specializations, it presents a rewarding path for those with the right skills and dedication.