Navigation Design

vigating the World of Navigation Design

Navigation design is the art and science of creating systems that allow users to move through a website, app, or any digital interface effectively and intuitively. It's about making it easy for people to find what they're looking for and understand where they are within a digital space. Think of it like the signage in a large building or the table of contents in a book; good navigation design makes the experience smooth and frustration-free. The field is a critical component of User Experience (UX) and User Interface (UI) design, directly impacting how users interact with and perceive a product.

Working in navigation design can be quite engaging. You get to be the architect of a user's journey, shaping how they explore and interact with a digital product. There's a satisfying challenge in organizing complex information in a way that feels simple and logical. Moreover, seeing users successfully and effortlessly navigate a system you designed can be incredibly rewarding. It's a field that blends creativity with analytical thinking, allowing you to make a tangible difference in how people experience technology.

Introduction to Navigation Design

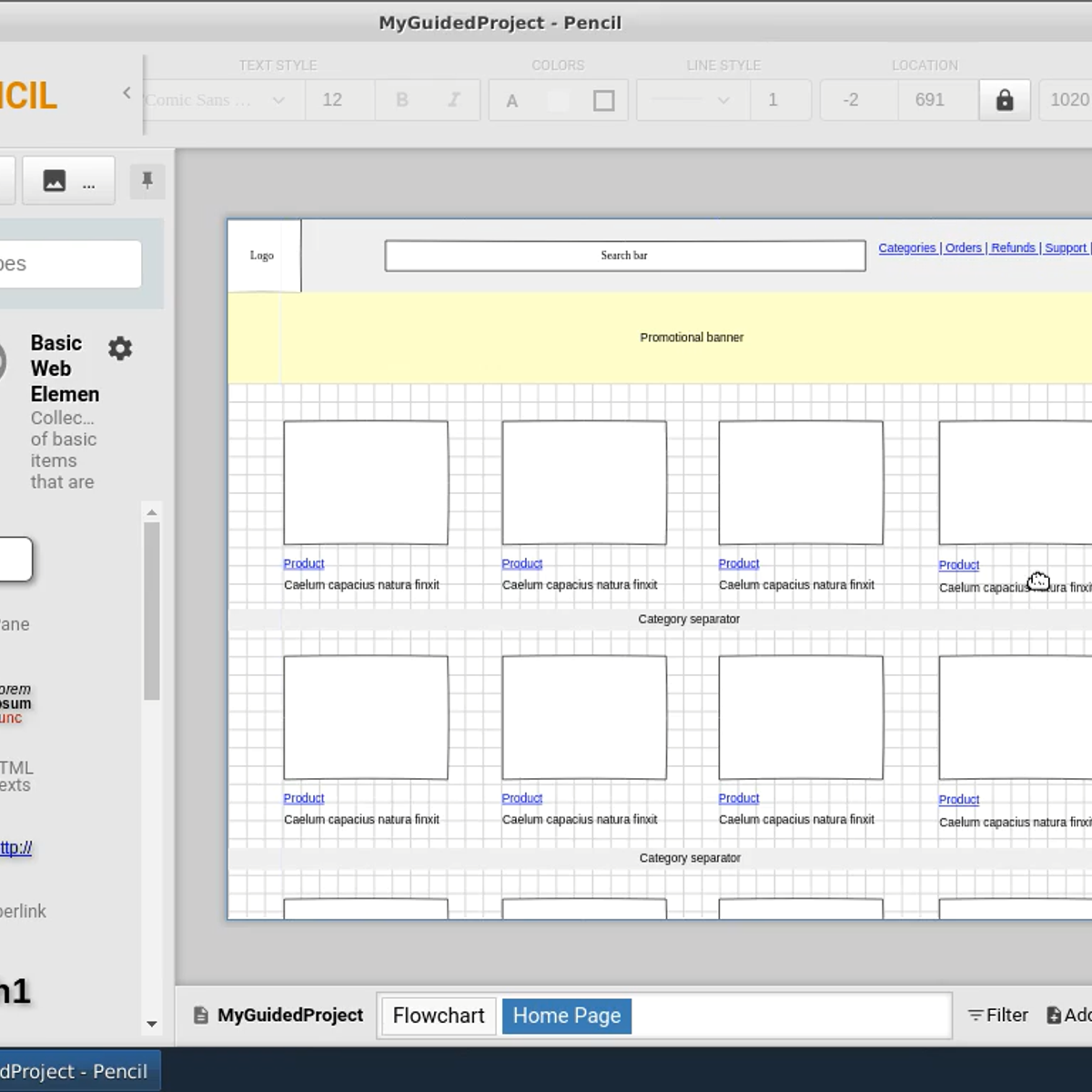

At its core, navigation design focuses on guiding users through an interface to achieve their goals. This involves the strategic placement and design of elements like menus, links, buttons, and search bars. Effective navigation is often described as "invisible" because when it's done well, users don't even notice it; they simply find what they need without a second thought.

Definition and Scope of Navigation Design

Navigation design encompasses the creation, analysis, and implementation of pathways that users take to move through a digital product, such as a website or application. It's not just about placing links on a page; it involves a deep understanding of user behavior, information hierarchy, and interaction principles. The scope of navigation design is broad, covering everything from the main menu of a large e-commerce site to the subtle cues that guide a user through a mobile app's features. It ensures that users can move from one point to another with minimal effort and confusion.

The ultimate goal is to empower users, making them feel confident and in control as they interact with the product. This involves careful consideration of how information is structured and presented, ensuring that pathways are clear and predictable. Good navigation anticipates user needs and provides intuitive routes to their desired destinations.

Furthermore, navigation design must often adapt to different contexts, such as various screen sizes or user tasks. This adaptability is key to providing a consistent and positive experience across all touchpoints. As digital products become more complex, the role of thoughtful navigation design becomes even more critical in ensuring usability and user satisfaction.

Role in User Experience (UX) and User Interfaces (UI)

Navigation design is a cornerstone of both User Experience (UX) and User Interface (UI) design. In UX, navigation is fundamental to how usable and enjoyable a product is. If users can't find what they need, their overall experience will be negative, regardless of how visually appealing the interface might be. Effective navigation enhances understanding, builds user confidence, and supports task completion, all of which are key components of a positive UX.

From a UI perspective, navigation design dictates the layout and appearance of navigational elements. This includes the visual design of menus, the clarity of labels, and the intuitiveness of interactive elements. The UI must effectively communicate the available navigation options and provide clear feedback to user actions. A well-designed UI makes the navigation system not only functional but also aesthetically pleasing and consistent with the overall brand identity.

Ultimately, navigation acts as the bridge between the user and the content or functionality of a digital product. It's a critical touchpoint that directly influences user satisfaction, engagement, and the ability to achieve goals within the interface. Therefore, a strong collaboration between UX and UI principles is essential for creating successful navigation systems.

These courses offer a solid introduction to the foundational concepts of user experience and interface design, which are intrinsically linked to navigation design.

You may also find these topics to be helpful for further exploration.

Key Principles: Clarity, Consistency, Predictability

Several key principles underpin effective navigation design, with clarity, consistency, and predictability being paramount. Clarity ensures that navigation options are easy to understand and that users know where a link or button will take them. This involves using clear, concise labels and recognizable icons. Ambiguous or jargon-filled terms can lead to confusion and frustration.

Consistency in navigation design means that similar elements look and behave in a similar way throughout the entire product. For example, the main navigation menu should appear in the same location and function identically on every page. This consistency helps users build a mental model of how the site or app works, making it easier to navigate as they become more familiar with it.

Predictability means that the navigation behaves in a way that users expect. When a user clicks on a menu item, the outcome should align with their expectations. This principle relies on established design patterns and conventions that users are already familiar with from other websites and applications. By adhering to these principles, designers can create navigation systems that feel intuitive and effortless to use.

The following books delve deeper into design principles that are highly relevant to creating effective navigation.

Historical Evolution of Navigation Systems

Understanding the history of navigation systems provides valuable context for current design challenges and future innovations. Navigation has evolved dramatically, from rudimentary physical guides to the sophisticated digital interfaces we use today. This journey reflects broader technological advancements and changing user expectations.

Pre-digital Navigation Systems (e.g., Maps, Signage)

Before the digital age, navigation relied on physical tools and environmental cues. Maps, meticulously drawn and updated, were the primary means of understanding spatial relationships and planning routes. Signage systems in cities and buildings played a crucial role in guiding people to their destinations. Think of street signs, building directories, and trail markers – these are all forms of pre-digital navigation systems.

These early systems relied on visual perception and the cognitive ability of individuals to interpret symbols and orient themselves in physical space. The principles of clarity and consistency were just as important then as they are now. A poorly designed map or confusing signage could easily lead someone astray. Early mariners, for instance, relied on star charts and compasses, tools that required significant skill and knowledge to use effectively. The development of the gyroscopic compass in 1907 was a significant advancement, providing a more reliable direction than magnetic compasses.

These pre-digital methods laid the groundwork for many concepts still relevant in digital navigation, such as the importance of clear hierarchies, logical pathways, and easily understandable symbols. The challenge was often the static nature of these tools; a printed map couldn't update itself with new roads or points of interest.

Transition to Digital Interfaces in the 1990s

The 1990s marked a significant turning point with the advent of digital interfaces and the rise of personal computing and the internet. Early websites and software applications began to incorporate digital navigation elements. Hyperlinks became the digital equivalent of pathways, allowing users to jump between different "pages" or sections of information. Early car navigation systems also started appearing, moving from experimental phases to commercially available products.

The first commercially available car navigation system, Honda's Electro Gyrocator, appeared in 1981, using inertial navigation. Etak's Navigator in 1985 used map-matching to improve dead reckoning. By 1987, Toyota introduced the first CD-ROM-based navigation system. The Eunos Cosmo in 1990 was the first production car with a built-in GPS navigation antenna system. These early digital systems often mimicked their physical counterparts. For example, website navigation menus often resembled a table of contents or an index. The concept of a "site map" emerged as a digital overview of a website's structure, similar to how a building directory provides an overview of its layout.

However, the transition also brought new challenges. Designers had to figure out how to represent complex information structures in a limited screen space. Usability issues were common, as there were few established conventions for digital navigation. The release of a more accurate GPS signal for civilian use in 2000 significantly boosted the capabilities and adoption of digital navigation, especially in automotive applications. This period was characterized by experimentation and the gradual development of the navigation patterns we are familiar with today.

Impact of Mobile Devices on Navigation Paradigms

The proliferation of mobile devices, particularly smartphones and tablets, in the late 2000s and 2010s profoundly impacted navigation design. Smaller screen sizes and touch-based interactions necessitated new approaches to navigation. Traditional navigation patterns, like extensive dropdown menus common on desktop websites, were often cumbersome and impractical on mobile screens.

This led to the rise of mobile-specific navigation patterns, such as the "hamburger" menu (a button with three horizontal lines that reveals a menu when tapped), tab bars at the bottom of app screens, and gesture-based navigation. The principle of "mobile-first" design emerged, encouraging designers to prioritize the mobile experience and then adapt it for larger screens. This shift forced designers to be more focused and efficient with their navigation, often leading to simpler and more intuitive interfaces overall.

Furthermore, mobile devices introduced new contextual possibilities for navigation. Location awareness, for example, allowed apps to provide real-time, turn-by-turn directions and location-specific information. The challenges of designing for mobile also highlighted the importance of accessibility, ensuring that navigation could be easily used by people with diverse abilities and in various contexts of use. Today, designing for a multitude of devices and screen sizes is a fundamental aspect of navigation design.

Core Principles of Effective Navigation Design

Effective navigation design is built upon a set of core principles that ensure users can find their way easily and efficiently. These principles guide designers in creating intuitive and user-friendly interfaces. Adhering to these tenets helps in crafting navigation systems that are not just functional but also enhance the overall user experience.

Hierarchy and Information Architecture

At the heart of effective navigation is a clear understanding and implementation of hierarchy and information architecture (IA). IA is the practice of organizing, structuring, and labeling content in an effective and sustainable way. It’s like creating a blueprint for your website or app, defining how information is grouped and how users will access it. A well-defined IA ensures that content is logically organized and that users can easily understand the relationships between different pieces of information.

Hierarchy, a key component of IA, involves arranging content in a structured manner, typically from broader categories to more specific subcategories. This helps users navigate from general information to the specific details they are looking for. Think of a library's classification system or the folder structure on your computer – these are examples of hierarchical organization. In digital navigation, this often translates into multi-level menus or breadcrumbs that show the user's current location within the hierarchy.

Without a solid information architecture and a clear hierarchy, navigation can become confusing and inefficient, leading to user frustration. Users should be able to predict where they will find certain information based on the established structure. Investing time in developing a robust IA is a critical first step in designing effective navigation.

These resources provide a deeper understanding of information architecture, a critical component of navigation design.

Visual Affordances and Feedback Mechanisms

Visual affordances are cues in an interface that suggest how an element can be used. For example, a button that looks raised or has a shadow "affords" clicking because it resembles a physical button you can press. Clear affordances help users understand what is interactive and what is not, reducing guesswork and making the interface more intuitive. This can include the shape, color, and styling of navigation elements.

Feedback mechanisms are equally important. When a user interacts with a navigation element, the system should provide immediate and clear feedback to acknowledge the action. This could be a visual change (e.g., a button changing color when hovered over or clicked), an auditory cue, or even haptic feedback on mobile devices. Feedback confirms to the user that their action has been registered and that the system is responding. Without adequate feedback, users might wonder if their click or tap was successful, leading to uncertainty and repeated actions.

Together, visual affordances and feedback mechanisms create a responsive and understandable navigation experience. They make the interaction feel more tangible and help users build confidence in using the interface. Designers must carefully consider how these cues are implemented to ensure they are clear, consistent, and support the user's goals.

Accessibility Standards (WCAG Compliance)

Accessibility in navigation design means creating interfaces that can be used by everyone, regardless of their abilities or disabilities. This includes people with visual, auditory, motor, or cognitive impairments. Adhering to established accessibility standards, such as the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), is crucial for creating inclusive navigation systems.

WCAG provides a wide range of recommendations for making web content more accessible. For navigation, this includes ensuring that all navigation elements can be operated via a keyboard (for users who cannot use a mouse), that link text is descriptive (so screen reader users understand the destination), and that there is sufficient color contrast between text and background (for users with low vision). It also involves providing clear and consistent navigation mechanisms across the entire site or app.

Designing for accessibility not only benefits users with disabilities but often improves the experience for all users. For instance, clear and descriptive link text is helpful for everyone, not just screen reader users. By making accessibility a core consideration from the outset, designers can create navigation systems that are truly universal and cater to the diverse needs of their audience. Tools and techniques exist to help evaluate and implement WCAG compliance, making it an integral part of the design process.

Cross-Platform Consistency

In today's multi-device world, users often interact with a product or service across various platforms – desktops, laptops, tablets, and smartphones. Maintaining cross-platform consistency in navigation design is vital for a seamless user experience. While the exact layout and specific navigation patterns might need to adapt to different screen sizes and input methods (e.g., mouse vs. touch), the underlying information architecture and core navigation principles should remain consistent.

This means that users should be able to find key information and features in roughly the same place, regardless of the device they are using. Terminology and labeling should also be consistent. If a section is called "My Account" on the website, it should ideally have the same name in the mobile app. This consistency reduces the learning curve when users switch between devices and reinforces their mental model of the product.

Achieving cross-platform consistency requires careful planning and a design system that can accommodate different contexts while preserving the core user experience. It's about finding the right balance between adapting to the specific capabilities and constraints of each platform and maintaining a familiar and predictable experience for the user. When done well, cross-platform consistency contributes significantly to user satisfaction and brand coherence.

Navigation Design in User Experience (UX)

Navigation design is a fundamental pillar of the overall user experience. How easily users can find their way around a digital product directly impacts their satisfaction, efficiency, and likelihood of achieving their goals. A well-thought-out navigation system can transform a frustrating experience into a delightful one.

Relationship Between Navigation and Task Completion Rates

There is a direct and significant relationship between the quality of navigation design and users' ability to complete tasks successfully. If users cannot easily find the features or information they need to accomplish a goal, task completion rates will inevitably suffer. Confusing menus, unclear labels, or illogical pathways can lead to users getting lost, frustrated, and ultimately abandoning the task or the product altogether.

Conversely, intuitive and efficient navigation guides users smoothly towards their objectives, increasing the likelihood of successful task completion. When navigation is clear and predictable, users spend less mental effort figuring out how to get around and more effort on the task itself. This leads to higher efficiency, reduced error rates, and a greater sense of accomplishment for the user.

Measuring task completion rates is a key metric in usability testing and provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of a navigation system. By analyzing where users struggle or drop off during a task, designers can identify pain points in the navigation and make targeted improvements. Ultimately, a primary goal of navigation design is to facilitate seamless task completion, which is a critical factor in overall user satisfaction and product success.

This course provides insights into redesigning user interfaces, which often involves rethinking navigation for better task completion.

User Testing Methodologies

User testing is an indispensable part of designing effective navigation. It involves observing real users as they interact with a prototype or live product to identify usability issues and gather feedback. Several methodologies are commonly used to test navigation design. One popular method is tree testing, which specifically evaluates the findability and labeling of information within a website's hierarchy, independent of the visual design. Participants are given tasks and asked to navigate a text-based representation of the site structure to find the relevant information.

Another common technique is first-click testing. This method assesses what users would click on first to complete a specific task on an interface. The first click is often a strong indicator of whether a user will ultimately succeed in their task. If users consistently click on the wrong element, it suggests a problem with the navigation's clarity or information scent. Usability testing, a broader methodology, involves observing users performing a series of tasks with a prototype or live product, often while thinking aloud. This provides rich qualitative data about their thought processes, pain points, and overall experience with the navigation.

A/B testing can also be employed to compare the performance of different navigation designs. This involves showing two or more versions of a navigation system to different user groups and measuring which version leads to better outcomes, such as higher task completion rates or faster task times. These methodologies, often used in combination, provide designers with actionable insights to iterate and improve navigation systems based on real user behavior and feedback.

For those interested in how users interact with digital products, this topic is highly relevant.

This career path is closely related to understanding user needs and testing designs.

Tools for Heatmap Analysis and Click Tracking

To gain deeper insights into how users interact with navigation, designers often utilize tools for heatmap analysis and click tracking. Heatmaps visually represent user activity on a webpage. There are different types of heatmaps: click maps show where users click most frequently, scroll maps indicate how far down a page users scroll, and move maps track mouse cursor movements.

Click tracking tools record every click users make on a page, providing quantitative data on which navigation elements are being used and which are being ignored. This data can reveal if users are clicking on non-interactive elements (indicating a potential affordance issue) or if critical navigation links are being overlooked. Analyzing click patterns can help identify popular navigation paths and areas where users might be struggling or confused.

These tools offer valuable data-driven insights that complement qualitative findings from user testing. For example, a heatmap might show that very few users are clicking on a particular menu item, prompting further investigation through usability testing to understand why. By combining these quantitative and qualitative data sources, designers can make more informed decisions about how to optimize navigation for better usability and engagement. Many analytics platforms and specialized UX tools offer heatmap and click tracking capabilities.

Career Pathways in Navigation Design

A career in navigation design can be rewarding, offering opportunities to shape how people interact with technology. It's a field that combines creativity, psychology, and technical understanding. As digital products become increasingly central to our lives, the demand for skilled designers who can create intuitive and effective navigation experiences continues to grow.

If you are considering a career pivot or are new to the field, it's natural to feel a mix of excitement and apprehension. The journey into navigation design, like any new career path, requires dedication and a willingness to learn. While the field can be competitive, particularly for entry-level roles, the growing importance of user experience across industries means that opportunities are available. Ground yourself in the fundamentals, build a strong portfolio, and be persistent in your efforts. Remember that many successful designers started with a passion for making things better and a commitment to understanding user needs. Your unique background and perspective can also be valuable assets in this evolving field.

Entry-Level Roles: UI Designer, UX Researcher

For those starting in navigation design, common entry-level roles include UI Designer and UX Researcher. While not solely focused on navigation, these roles provide a strong foundation and involve significant work related to how users find their way through a product. A UI Designer will focus on the visual aspects of navigation – how menus, buttons, and links look and feel, ensuring they are clear, consistent, and aesthetically pleasing. They translate wireframes and prototypes into tangible interface elements that users interact with.

A UX Researcher, on the other hand, focuses on understanding user needs, behaviors, and motivations through various research methods like interviews, surveys, and usability testing. Their findings directly inform navigation design by identifying pain points in existing navigation, understanding user mental models, and validating design decisions. Both roles require a keen eye for detail, empathy for users, and strong problem-solving skills.

Gaining experience in these roles allows individuals to develop a deep understanding of user-centered design principles, which are crucial for specializing in navigation design. Portfolio projects, even conceptual ones, that specifically address navigation challenges can be very beneficial when applying for these positions. Online courses and bootcamps can also provide structured learning and project opportunities to build foundational skills.

These careers are excellent starting points or related paths for those interested in navigation design.

Mid-Career Specialization Options

As professionals gain experience in UI/UX, several mid-career specialization options related to navigation design become available. One such path is specializing as an Information Architect. Information Architects focus specifically on organizing and structuring content, creating sitemaps, defining labeling systems, and ensuring that the overall information hierarchy is logical and user-friendly. This role is critical for large, complex websites and applications where effective navigation is paramount.

Another specialization is a Usability Engineer or Analyst. [rrcd8w] These professionals focus on evaluating and improving the ease of use of digital products. This often involves conducting in-depth usability testing, analyzing user data, and identifying specific issues within the navigation flow that hinder task completion or cause frustration. They work closely with designers and developers to implement solutions that enhance usability.

Some designers may also choose to specialize in a particular type of navigation, such as mobile navigation, voice navigation, or navigation for complex enterprise software. These specialized roles require a deep understanding of the unique challenges and best practices associated with those specific contexts. Continuous learning and staying updated with emerging technologies and design patterns are key to success in these specialized mid-career paths.

For those looking to specialize further, these career paths offer focused opportunities.

Leadership Positions: Product Design Director

With significant experience and a proven track record, individuals in navigation design and broader UX fields can advance to leadership positions such as Product Design Director, Head of UX, or Chief Experience Officer. These roles involve overseeing the entire design strategy and execution for a product or range of products. While not solely focused on navigation, a deep understanding of navigation principles is essential, as it forms a critical part of the overall user experience.

In these leadership roles, responsibilities often include managing and mentoring a team of designers, setting design vision and standards, collaborating with product management and engineering leaders, and ensuring that design decisions align with business goals. They are responsible for fostering a user-centered design culture within the organization and advocating for the user at a strategic level. Strong communication, leadership, and strategic thinking skills are paramount.

The path to such leadership positions typically involves a progression through more senior design roles, demonstrating impact on product success, and developing a strong portfolio of work. While the journey can be demanding, the opportunity to shape the user experience at a high level and influence product direction can be immensely fulfilling. Industry reports suggest a growing demand for UX professionals, although the market can be competitive. Staying adaptable and continuously honing both design and leadership skills is key for long-term career growth in this dynamic field.

This career path represents a potential leadership trajectory.

Formal Education Pathways

For those aspiring to enter the field of navigation design, several formal education pathways can provide a strong foundation. These routes typically involve university-level study, offering structured learning environments and opportunities to delve deep into relevant theories and practices. While formal education is not the only path, it can equip individuals with critical thinking skills and a comprehensive understanding of the discipline.

Relevant Undergraduate Degrees (HCI, Graphic Design)

Several undergraduate degrees can be particularly relevant for a career in navigation design. A degree in Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) is perhaps one of the most directly applicable. HCI programs focus on the design, evaluation, and implementation of interactive computing systems for human use. Students learn about user psychology, research methods, interaction design principles, and usability testing – all crucial for navigation design.

A degree in Graphic Design can also provide a strong foundation, particularly for the visual aspects of navigation. [hqxfpa] Graphic design programs emphasize visual communication, typography, color theory, and layout, which are essential for creating clear and aesthetically pleasing navigation interfaces. Students often develop a strong portfolio of visual work, which can be an asset when applying for UI-focused roles.

Other relevant degrees might include psychology, cognitive science (which explore how people think and perceive information), communication design, or even computer science with a focus on user interface development. The key is to look for programs that offer coursework and projects related to user-centered design, information organization, and interactive system design. Many universities also offer interdisciplinary programs that combine elements from these different fields.

This topic is closely related to the visual aspects of navigation design.

Graduate Programs Focusing on Interaction Design

For individuals seeking more specialized knowledge or looking to deepen their expertise, graduate programs focusing on Interaction Design (IxD) can be an excellent choice. [7cfmpy] Master's degrees in Interaction Design, HCI, UX Design, or related fields offer advanced coursework and research opportunities in areas directly relevant to navigation design. These programs often delve deeper into topics like information architecture, user research methodologies, service design, and emerging interactive technologies.

Graduate programs typically involve more intensive project work, allowing students to build a sophisticated portfolio. They also provide opportunities for collaboration with peers and faculty, and often have strong connections with industry, which can lead to internships and job placements. A graduate degree can be particularly beneficial for those aiming for research-oriented roles, specialized positions, or academic careers.

When considering graduate programs, it's important to research the specific curriculum, faculty expertise, and industry connections of each program. Look for programs that align with your career goals and offer opportunities to focus on aspects of navigation and user experience that you are most passionate about. Some programs may also offer specializations in areas like mobile design, game design, or data visualization, all of which have unique navigation challenges.

This topic and career path are central to advanced studies in designing interactive systems.

Capstone Project Expectations

Many undergraduate and graduate programs in design-related fields culminate in a capstone project. This is a significant, often semester-long or year-long, project where students apply the knowledge and skills they have acquired throughout their studies to solve a real-world or complex hypothetical design problem. For students interested in navigation design, the capstone project offers an excellent opportunity to focus on this area.

Expectations for a capstone project are typically high. Students are expected to conduct thorough research, including user research and competitive analysis, to define the problem and identify user needs. They then go through an iterative design process, developing concepts, creating wireframes and prototypes, and testing their designs with users. The final deliverables often include a detailed design solution, a comprehensive report documenting the process and rationale, and a presentation of the work.

A capstone project focused on a navigation-heavy system, such as a complex website redesign, a mobile application with intricate features, or a novel interactive experience, can serve as a powerful portfolio piece. It allows students to demonstrate their ability to tackle challenging design problems, apply user-centered design methodologies, and create well-reasoned and effective navigation solutions. Prospective employers often look closely at capstone projects as evidence of a candidate's skills and potential.

Self-Directed Learning Strategies

For individuals who prefer a less traditional route or are looking to transition careers, self-directed learning can be a viable and effective way to gain the skills and knowledge needed for navigation design. This path requires discipline, proactivity, and a passion for continuous learning, but it offers flexibility and the ability to tailor your learning to your specific interests and goals.

Embarking on a self-directed learning journey can feel daunting at first, especially if you're balancing it with other commitments. It's important to set realistic goals and celebrate small victories along the way. The online learning landscape offers a wealth of resources, but it can also be overwhelming. Start by identifying the core competencies of navigation design and gradually build your knowledge. Remember that many successful designers are self-taught or have supplemented formal education with ongoing self-directed learning. Your determination and the portfolio you build will speak volumes.

Building Portfolio Projects Without Formal Credentials

A strong portfolio is arguably the most important asset for aspiring navigation designers, regardless of their educational background. For self-directed learners, creating compelling portfolio projects is crucial for demonstrating skills and landing a job. One effective approach is to undertake unsolicited redesign projects. Choose an existing website or app whose navigation you believe could be improved, conduct your own user research (even if it's informal, like interviewing friends or family), and then redesign the navigation, documenting your process and rationale.

Another strategy is to create conceptual projects from scratch. Identify a problem or a need that could be addressed with a digital solution, and then design the product, paying close attention to its navigation. This allows you to showcase your creativity and problem-solving abilities. Volunteering your design skills for non-profit organizations or small businesses can also provide real-world project experience and valuable portfolio pieces.

When building your portfolio, focus on quality over quantity. Each project should clearly articulate the problem, your design process (including research, ideation, prototyping, and any testing you were able to do), and the final solution. Explain your navigation design decisions and how they address user needs and improve the user experience. Even without formal credentials, a well-crafted portfolio that demonstrates a strong understanding of design principles and a user-centered approach can make a powerful impression on potential employers. OpenCourser offers a vast library of courses that can equip you with the foundational knowledge to tackle such projects.

This course is an excellent starting point for understanding how to structure information, a key skill for portfolio projects focusing on navigation.

This book provides practical guidance on designing web navigation, which can inspire portfolio projects.

Open-Source Tool Proficiency (Figma, Adobe XD)

Proficiency in industry-standard design tools is essential for anyone pursuing a career in navigation design. Fortunately, many powerful design tools are available, some of which are open-source or offer generous free tiers, making them accessible for self-directed learners. Tools like Figma and Adobe XD are widely used in the industry for creating wireframes, prototypes, and high-fidelity interface designs.

Figma is a browser-based collaborative design tool that has gained immense popularity for its real-time collaboration features and robust vector editing capabilities. Adobe XD is another powerful vector-based UX design tool that offers features for design, prototyping, and sharing. Learning these tools involves understanding their interface, mastering their features for creating and manipulating design elements, and learning how to build interactive prototypes to simulate navigation flows.

Numerous online tutorials, courses, and communities are dedicated to teaching these tools. Many self-directed learners find that working through project-based tutorials is an effective way to build proficiency. As you learn, try to replicate existing navigation designs or create your own from scratch. The ability to quickly and effectively use these tools will be expected in most design roles, and showcasing your tool proficiency through your portfolio projects is key. Familiarity with tools like Axure RP, known for more complex prototyping, can also be beneficial. [gjdwec]

These courses can help you get started with tools commonly used in navigation and UI/UX design.

Exploring different design software is a good way to broaden your skillset.

Participating in Design Sprints/Hackathons

Participating in design sprints or hackathons can be an invaluable experience for self-directed learners. These events provide an opportunity to work collaboratively in a fast-paced environment, tackle real or simulated design challenges, and gain practical experience in a short amount of time. Design sprints are typically time-boxed processes (often a few days to a week) where a team works intensively to solve a design problem, from understanding the problem to prototyping and testing a solution.

Hackathons, while often associated with coding, increasingly include design tracks or welcome designers to collaborate with developers and product thinkers. These events challenge participants to come up with innovative solutions to specific themes or problems, often under tight deadlines. For aspiring navigation designers, this can be a chance to contribute your skills in information architecture, wireframing, and prototyping to a team project.

Beyond the learning experience, design sprints and hackathons are excellent networking opportunities. You get to meet and collaborate with other designers, developers, and industry professionals, which can lead to mentorship, job opportunities, or simply new connections in the field. Adding a project from a design sprint or hackathon to your portfolio can also demonstrate your ability to work in a team, think creatively under pressure, and deliver results quickly.

Emerging Trends in Navigation Design

The field of navigation design is constantly evolving, driven by technological advancements and changing user expectations. Staying abreast of emerging trends is crucial for designers who want to create cutting-edge and effective user experiences. These trends often point towards more intuitive, personalized, and immersive ways for users to interact with digital information and environments.

Voice-Activated Navigation Systems

Voice-activated navigation systems are becoming increasingly prevalent, particularly with the rise of smart speakers, virtual assistants on smartphones, and in-car infotainment systems. Instead of relying on visual menus and clicks, users can interact with these systems using natural language commands. For example, asking a smart speaker for directions, or telling your car's navigation system to "find the nearest gas station."

Designing for voice navigation presents unique challenges and opportunities. Designers must consider how to structure information so it can be easily accessed and understood through spoken dialogue. This involves careful attention to command phrasing, an understanding of natural language processing (NLP) capabilities and limitations, and designing clear voice feedback. The absence of a visual interface (or a supplementary one) means that clarity and conciseness in voice interactions are paramount. As NLP technology continues to improve, voice-activated navigation is likely to become even more sophisticated and integrated into a wider range of digital experiences.

The implications for designers include thinking about "conversational flows" rather than just visual hierarchies, and considering how to handle ambiguity or errors in voice commands. This trend also highlights the growing importance of multimodal interaction, where users might switch seamlessly between voice, touch, and visual interfaces.

Augmented Reality Wayfinding

Augmented Reality (AR) wayfinding is an exciting emerging trend that overlays digital navigation information onto the user's real-world view, typically through a smartphone camera or AR glasses. Imagine looking through your phone's camera and seeing arrows and directions superimposed on the street in front of you, guiding you to your destination. Or, in an airport or large shopping mall, seeing digital signs appear that point you towards your gate or a specific store.

AR wayfinding has the potential to make navigation in complex physical environments much more intuitive and less stressful. It bridges the gap between the digital map and the physical world, providing a more direct and contextual form of guidance. For designers, this means thinking about how to present information clearly and unobtrusively within the user's field of view, ensuring that digital overlays enhance rather than obstruct their perception of the real world.

Challenges in AR wayfinding include ensuring accurate positioning and orientation, designing intuitive AR interfaces, and addressing potential issues like battery consumption and user distraction. However, as AR technology matures and becomes more accessible, AR-powered navigation is expected to find applications in various domains, from urban navigation and tourism to indoor navigation in large venues and industrial settings.

AI-Driven Adaptive Interfaces

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is playing an increasingly significant role in creating adaptive navigation interfaces. These are interfaces that can learn from user behavior and context to personalize and optimize the navigation experience in real-time. For example, an e-commerce website might dynamically reorder menu items based on a user's browsing history, or a mobile app might surface frequently used features more prominently.

AI can analyze vast amounts of user data to identify patterns and predict user needs, allowing the navigation to adapt proactively. This could involve simplifying navigation for new users, offering shortcuts for experienced users, or adjusting the interface based on the user's current task or location. The goal is to make navigation feel more intuitive and efficient by tailoring it to the individual user. According to a study referenced by Design Shack, adaptive user interfaces can boost user engagement rates by up to 31% and user task completion rates by 22%.

However, designing AI-driven adaptive interfaces also raises ethical considerations, such as data privacy and the potential for algorithmic bias. Designers need to ensure that personalization efforts are transparent and provide value to the user without feeling intrusive or manipulative. As AI technology continues to advance, we can expect to see more sophisticated and context-aware adaptive navigation systems that aim to create truly seamless and personalized user journeys.

Ethical Considerations in Navigation Design

While the primary goal of navigation design is to help users, designers must also be aware of the ethical implications of their work. The way navigation is structured can influence user behavior, sometimes in ways that may not be in the user's best interest. It's important for designers to approach their work with a strong sense of responsibility and a commitment to ethical practices.

Dark Patterns in User Flow Design

Dark patterns are design techniques that trick or manipulate users into taking actions they might not otherwise choose. In the context of navigation, dark patterns can be used to make it difficult for users to find certain information (like how to cancel a subscription or delete an account), or to steer them towards choices that benefit the business rather than the user. This could involve intentionally confusing navigation labels, hiding important options in obscure locations, or creating overly complex pathways for undesirable actions.

For example, a "roach motel" dark pattern makes it easy to get into a situation (e.g., sign up for a service) but very difficult to get out of it. Another example is "misdirection," where the design purposefully focuses your attention on one thing to distract you from another. These practices erode user trust and can lead to negative user experiences.

Ethical navigation design prioritizes transparency and user autonomy. It means making all options clear and accessible, and ensuring that users can easily navigate to achieve their intended goals, even if those goals (like unsubscribing) are not what the business would prefer. Designers have a responsibility to advocate for ethical practices and to avoid using manipulative techniques in their navigation designs.

Addictive Interface Mechanisms

While not always directly related to primary navigation structures like menus, certain interface design elements and user flows can contribute to addictive or compulsive user behavior. This can involve features that encourage constant checking, endless scrolling, or a fear of missing out (FOMO). While the goal of engaging users is often legitimate, designers should be mindful of the potential for their designs to cross the line into promoting unhealthy usage patterns.

For instance, the design of notification systems, content feeds, and reward mechanisms can all influence how frequently and intensely users interact with a product. If navigation or interface elements are designed to exploit psychological vulnerabilities to keep users hooked, it raises ethical concerns. This is particularly relevant in social media, gaming, and other applications designed for high engagement.

Ethical designers consider the well-being of their users and strive to create experiences that are engaging but also respectful of users' time and attention. This might involve designing features that promote mindful usage, providing users with more control over notifications and content consumption, or avoiding design patterns known to be associated with compulsive behavior. The conversation around digital well-being is growing, and designers play a crucial role in shaping healthier digital environments.

Cultural Bias in Iconography

Icons are a common element in navigation design, used to visually represent actions, objects, or concepts. However, the meaning of icons can be culturally specific. An icon that is clear and intuitive in one culture might be confusing or even offensive in another. This is an important ethical consideration, especially for products with a global audience.

For example, hand gestures, symbols, or colors can have vastly different connotations across cultures. Using an icon that relies on a culturally specific metaphor can lead to misinterpretation and a poor user experience for a segment of your audience. Designers need to be aware of these potential biases and strive to use iconography that is as universally understandable as possible, or to provide alternative text labels for clarity.

Conducting user research with diverse cultural groups can help identify potential issues with iconography and other visual elements in navigation. When designing for a global audience, it may be necessary to adapt or localize navigation elements to ensure they are culturally appropriate and effective in different regions. The goal is to create inclusive navigation systems that are accessible and understandable to all users, regardless of their cultural background.

Frequently Asked Questions

Navigating a new field or career path often comes with many questions. Here are some common inquiries about navigation design, aimed at providing clear and helpful answers for those exploring this exciting area.

Is coding required for navigation design roles?

Generally, deep coding skills are not a primary requirement for most navigation design roles, especially those focused on UX research, information architecture, or visual UI design. Designers typically use specialized design and prototyping tools like Figma or Adobe XD to create their deliverables. However, a basic understanding of web technologies (HTML, CSS, JavaScript) can be very beneficial. It helps designers understand the technical possibilities and constraints, communicate more effectively with developers, and create designs that are more feasible to implement. Some roles, particularly those that blur the lines between design and front-end development (often called UX Engineer or UI Developer), will require stronger coding skills.

How competitive is the job market?

The job market for UX and UI design, including roles involving navigation design, can be competitive, especially for entry-level positions. Many people are drawn to the field due to its creative nature and impact on technology. However, the demand for skilled UX professionals is also growing as more companies recognize the importance of good design for business success. Factors that can help you stand out include a strong portfolio showcasing practical skills and problem-solving abilities, proficiency in industry-standard tools, and a good understanding of user-centered design principles. Networking and continuous learning are also important. While some reports indicate a slowdown in hiring in certain tech sectors recently, the long-term outlook for UX professionals is generally considered positive.

Can navigation design skills transfer to other UX specialties?

Absolutely. The skills developed in navigation design are highly transferable to other UX specialties. Core competencies like understanding user behavior, information architecture, wireframing, prototyping, usability testing, and applying user-centered design principles are foundational to all areas of UX. For example, an understanding of how users navigate information is crucial for content strategy. Skills in creating clear and intuitive flows are vital for interaction design. Experience in user research for navigation directly applies to broader UX research roles. Many UX professionals often work across different specializations throughout their careers, and a strong grounding in navigation design provides a versatile skillset.

What industries hire navigation designers?

Navigation designers (or UX/UI designers with strong navigation skills) are hired across a wide range of industries. The technology sector is a major employer, including software companies, web development agencies, and mobile app developers. E-commerce is another significant industry, as effective navigation is critical for online sales. Financial services, healthcare, education, entertainment, and government sectors also increasingly rely on digital products and services, creating demand for designers who can create intuitive user experiences. Essentially, any organization that has a digital presence and wants to ensure its users can easily find information and complete tasks will need expertise in navigation design.

How important is portfolio vs. formal education?

Both a strong portfolio and formal education can be valuable, but in the design field, the portfolio often carries more weight, especially for entry-level and mid-career roles. A portfolio provides tangible evidence of your skills, your design process, and your ability to solve real-world problems. It allows employers to see what you can do. Formal education (like a degree in HCI or graphic design) can provide a strong theoretical foundation, critical thinking skills, and a structured learning environment. However, many successful designers are self-taught or have come from unrelated fields, demonstrating their capabilities through outstanding portfolio work and continuous learning. Ultimately, a combination of relevant knowledge (whether gained formally or informally) and a compelling portfolio that showcases practical application of that knowledge is the ideal scenario.

What are common career progression bottlenecks?

Common career progression bottlenecks in UX and navigation design can include a lack of opportunities for more strategic or leadership roles within a current company. Sometimes, designers may find themselves pigeonholed into specific types of tasks (e.g., only visual design or only wireframing) without chances to broaden their skillset or take on more responsibility. Keeping skills up-to-date with evolving technologies and design trends is also crucial; failing to do so can hinder advancement. Another bottleneck can be the challenge of demonstrating measurable business impact from design work, which becomes increasingly important for senior and leadership roles. Building soft skills, such as communication, collaboration, and leadership, is also vital for career progression beyond individual contributor roles.

We hope this exploration of navigation design has provided you with a comprehensive overview and valuable insights. Whether you're just starting to explore this field or looking to deepen your existing knowledge, the journey of learning and creating in navigation design is a continuous and rewarding one. With a vast array of online courses and resources available on OpenCourser, you have the tools at your fingertips to build a strong foundation and stay ahead in this dynamic field. Remember to check out the OpenCourser Learner's Guide for tips on making the most of your online learning journey.