Science Librarian

Science Librarian: Bridging Research and Knowledge

A Science Librarian serves as a vital link between the vast world of scientific information and the researchers, students, and professionals who need it. This role involves much more than managing book collections; it encompasses guiding research, teaching information navigation skills, curating digital resources, and ensuring access to the latest scientific discoveries across various disciplines like biology, chemistry, physics, engineering, and more. They are specialists in both library science and one or more scientific fields, blending these areas to support knowledge creation and dissemination.

Working as a Science Librarian offers the chance to engage deeply with cutting-edge research across diverse scientific domains without necessarily being at the lab bench. It provides opportunities to collaborate closely with faculty and students, contributing directly to their academic and research success. The field is dynamic, constantly evolving with new technologies and changing methods of scholarly communication, making it an intellectually stimulating career path for those passionate about both science and information access.

Introduction to Science Librarianship

Defining the Modern Science Librarian

The modern Science Librarian is an information professional with specialized knowledge in scientific disciplines. They work primarily in academic institutions, research centers, government agencies, or corporations with significant research and development arms. Their fundamental role is to facilitate access to and effective use of scientific information resources.

This involves understanding the specific information needs of scientists, researchers, and students within various fields. They curate collections, provide research assistance, offer instruction on information literacy, and manage complex digital datasets and repositories. They act as expert navigators in the increasingly complex landscape of scientific publishing and data.

Essentially, they are partners in the research process. They help formulate search strategies, locate hard-to-find data or literature, advise on publishing options, and increasingly, assist with managing and preserving research data according to funder mandates and best practices.

A Brief History of Science Information

The role of managing scientific knowledge has evolved significantly over centuries. Initially, libraries associated with scientific societies or universities held collections of printed books and journals. Librarians focused primarily on acquisition, cataloging, and preservation of these physical materials.

The mid-20th century saw the "information explosion," particularly in science and technology, driven by increased research funding and output. This necessitated new methods for organizing and retrieving information, leading to the development of indexing and abstracting services and specialized subject librarians.

The digital revolution transformed the field entirely. The shift from print to electronic journals, the rise of large databases, and the advent of the internet required librarians to develop technical skills alongside their subject expertise. Today, managing digital resources, understanding data management, and navigating open access models are central to the profession.

These books offer insights into the philosophical underpinnings and historical context of scientific knowledge, which can enrich a Science Librarian's perspective.

The Role in Research and Academia

Within academic and research settings, Science Librarians play a critical role in supporting the institution's mission. They are often embedded within specific science or engineering departments, fostering close relationships with faculty and students. Their primary objective is to enhance research productivity and learning outcomes.

They achieve this by ensuring the library's collections align with the research and teaching needs of the departments they serve. This involves selecting journals, databases, datasets, and other specialized resources. They also provide tailored research consultations, assisting with literature reviews, data discovery, and citation analysis.

Furthermore, Science Librarians are educators, teaching students critical information literacy skills. This includes how to effectively search databases, evaluate scientific sources, understand ethical use of information (like avoiding plagiarism), and manage citations. They empower users to become independent and discerning consumers and producers of scientific information.

Key Responsibilities of a Science Librarian

Building and Managing Scientific Collections

A core responsibility is developing and maintaining collections of scientific resources. This involves selecting books, journals, databases, datasets, software, and other materials relevant to the specific scientific disciplines served. It requires a deep understanding of the subject areas, the curriculum, and current research trends within the institution.

Collection development is not just about acquisition; it also involves managing budgets, negotiating with vendors, and making decisions about retaining or deselecting materials. Librarians analyze usage statistics and user feedback to ensure the collection remains relevant and cost-effective, especially given the high cost of many scientific resources.

With the shift towards digital resources, managing electronic collections is paramount. This includes overseeing access mechanisms (like IP authentication or proxy servers), troubleshooting technical issues, and understanding licensing agreements. They also play a role in preserving digital content for long-term access.

Supporting the Research Lifecycle

Science Librarians provide crucial support throughout the entire research lifecycle. At the outset, they assist researchers in defining research questions, conducting comprehensive literature reviews, and identifying relevant funding opportunities. They are experts in navigating complex scientific databases and search interfaces.

During the research process, they help locate specific data, methodologies, or protocols. Increasingly, they advise on research data management planning, helping researchers comply with funder mandates for data sharing and preservation. This might involve guidance on metadata standards, data repositories, and data citation practices.

As research concludes, librarians can assist with identifying appropriate journals for publication, understanding author rights and open access options, and measuring research impact using tools like citation analysis and bibliometrics. They support the dissemination and evaluation phases of research.

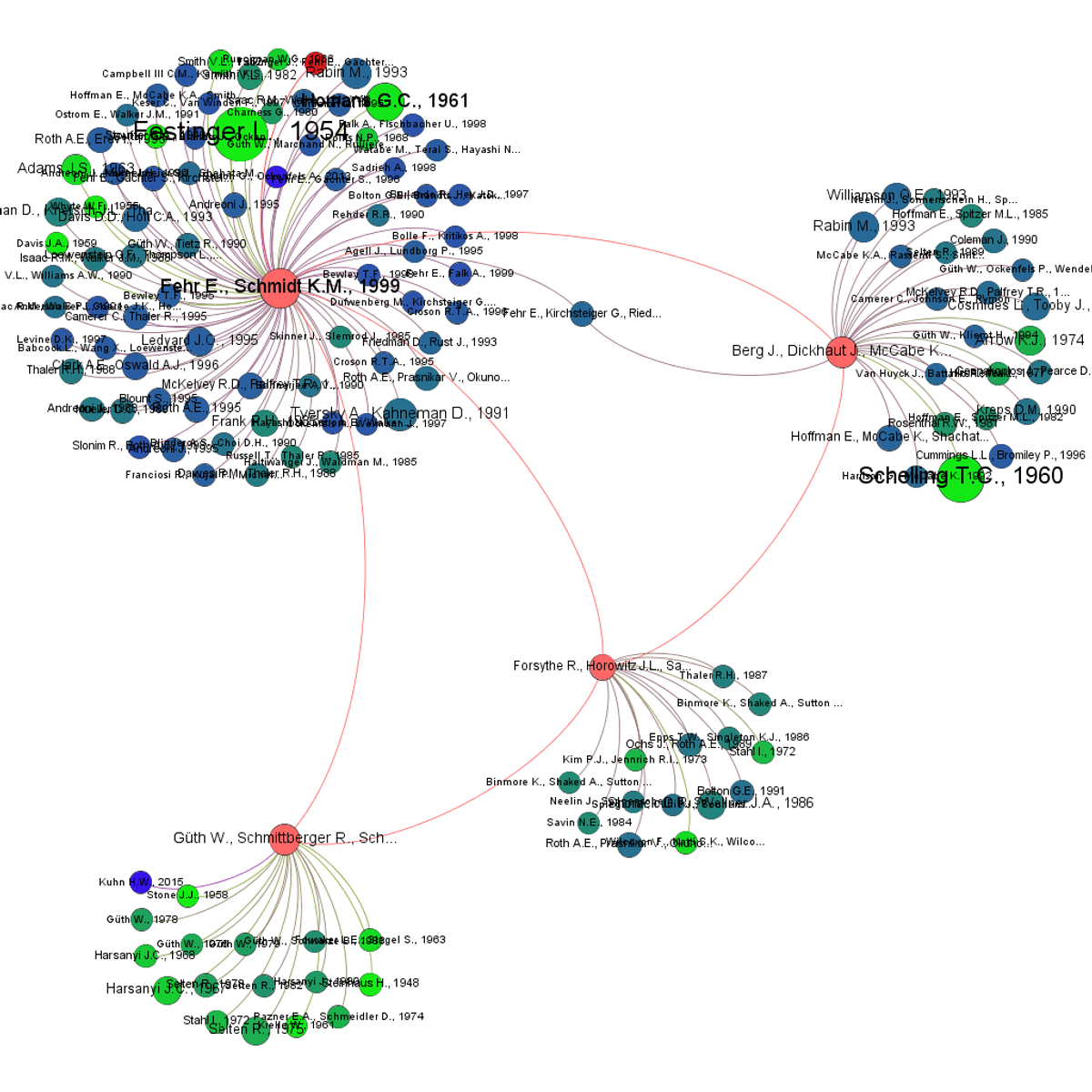

Understanding bibliometrics can be useful for supporting research evaluation. This course provides an introduction to citation analysis.

Teaching Information Literacy

Information literacy instruction is a key teaching function for Science Librarians. They design and deliver workshops, course-integrated sessions, and online tutorials to equip students and researchers with the skills needed to find, evaluate, and use scientific information effectively and ethically.

Topics covered often include advanced database searching techniques, critical evaluation of scientific literature (identifying bias, assessing methodology), understanding the scholarly communication process (peer review, publication models), citation management using tools like Zotero or EndNote, and avoiding plagiarism.

The goal is to foster critical thinking and lifelong learning skills applicable beyond specific assignments. They tailor instruction to different levels, from introductory undergraduate courses to advanced graduate seminars, adapting content to the specific needs of the discipline and audience.

These courses focus on the broader concepts of science literacy and communication, which are foundational to the instructional role of a Science Librarian.

Navigating the Digital Landscape

Managing digital resources is a central aspect of the modern Science Librarian's role. This involves selecting, acquiring, and providing access to a vast array of electronic journals, e-books, databases, and specialized scientific software. They must understand licensing terms, access models, and authentication methods.

Science Librarians are often involved in managing institutional repositories (IRs). These platforms collect, preserve, and provide access to the scholarly output of an institution, such as theses, dissertations, preprints, and research data. Managing an IR requires technical understanding and knowledge of metadata standards.

They also stay abreast of developments in digital scholarship tools and platforms, such as data visualization software, electronic lab notebooks, and collaborative research environments. They may provide support or training on these tools to enhance research workflows.

Essential Skills for Science Librarians

Mastering Scientific Domains

A strong foundation in one or more scientific or technical fields is highly advantageous, often considered essential, for a Science Librarian. While an advanced degree (Master's or PhD) in a science field is not always mandatory, a bachelor's degree in a relevant STEM discipline is common and provides the necessary subject literacy.

This subject expertise allows the librarian to understand the specific terminology, research methodologies, and information needs of the scientists and students they support. It enables them to communicate effectively with researchers, conduct more relevant literature searches, and make informed decisions about collection development.

Continuous learning is crucial to keep up with advancements in the scientific fields they support. Attending seminars, reading scientific literature, and engaging with researchers helps maintain subject currency. This deep understanding builds credibility and trust with the user community.

These courses cover diverse scientific topics, reflecting the breadth of knowledge a Science Librarian might engage with.

Technical Proficiency

Science Librarians need a range of technical skills to manage information resources effectively. Proficiency in searching specialized scientific databases (like PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, SciFinder) is fundamental. Understanding database structures, search syntax, and indexing principles is key.

Familiarity with library-specific technologies is also important. This includes Integrated Library Systems (ILS) for managing library operations, discovery layers that provide a unified search interface, and systems for managing electronic resources and authentication (like proxy servers).

Knowledge of metadata standards (e.g., Dublin Core, MODS, MARC) used for describing resources, particularly in digital repositories, is increasingly valuable. Experience with institutional repository platforms (like DSpace, Samvera) and data curation tools may also be required, especially in roles focused on digital scholarship or research data management.

While not always required, basic web development skills (HTML, CSS) or scripting abilities (Python) can be beneficial for customizing library services or automating tasks.

This course explores using 3D visualization for science communication, touching upon relevant technical skills.

Effective Communication and Collaboration

Strong communication and interpersonal skills are paramount for Science Librarians. They interact with a diverse range of stakeholders, including undergraduate students, graduate researchers, faculty members, IT staff, and library colleagues. Adapting communication style to suit the audience is crucial.

Clear and concise communication is needed for reference interviews (understanding user needs), instructional sessions, presentations, and writing reports or documentation. Active listening is essential to accurately grasp research questions or information challenges.

Collaboration is also key. Science Librarians often work closely with faculty to integrate information literacy into the curriculum, partner with IT departments on technical issues, and collaborate with other librarians on projects or service development. Building strong working relationships across campus or within an organization is vital for success.

These courses focus on effective communication, specifically within a scientific context.

Staying Ahead: Trends in Scholarly Communication

The landscape of scientific publishing and information sharing is constantly changing. Science Librarians must stay informed about major trends in scholarly communication to effectively advise researchers and shape library services. This requires ongoing professional development and trend analysis.

Key areas include the evolution of open access models (Gold, Green, Diamond OA), funder mandates for public access to research outputs, and the rise of preprint servers (like arXiv, bioRxiv). Understanding copyright, author rights, and institutional policies related to scholarly sharing is essential.

Other important trends involve research data management best practices, the development of persistent identifiers (like DOIs, ORCIDs), new methods for assessing research impact (altmetrics), and the ethical considerations surrounding artificial intelligence in research and publishing. Awareness of these shifts allows librarians to provide relevant guidance and anticipate future needs.

Formal Education Pathways

Laying the Groundwork: Undergraduate Studies

While there isn't one single required undergraduate major, a background in a science, technology, engineering, or mathematics (STEM) field is highly beneficial for aspiring Science Librarians. A bachelor's degree in biology, chemistry, physics, computer science, engineering, or a related area provides the foundational subject knowledge needed to understand scientific literature and communicate effectively with researchers.

However, individuals with strong undergraduate degrees in humanities or social sciences can also pursue this career, particularly if they complement their education with relevant science coursework or demonstrate a strong aptitude for and interest in scientific information. Strong analytical, research, and communication skills developed in any rigorous undergraduate program are valuable.

Regardless of major, coursework in statistics, computer science, and technical writing can be advantageous. Gaining experience working or volunteering in a library, especially an academic or special library, during undergraduate studies can also provide valuable exposure and strengthen an application for graduate school.

The Gateway: Master of Library and Information Science (MLIS)

The standard professional credential for librarians in North America, including Science Librarians, is a Master's degree in Library and Information Science (MLIS), Master of Library Science (MLS), or a similar title. Crucially, programs accredited by the American Library Association (ALA) are often required or strongly preferred by employers, especially in academic settings.

MLIS programs typically cover core library science principles such as cataloging, classification, reference services, collection development, information technology, and library management. Students interested in science librarianship should look for programs offering specializations, concentrations, or coursework relevant to science/technology librarianship, academic librarianship, data management, or digital libraries.

Many MLIS programs can be completed online, offering flexibility for those balancing work or other commitments. Programs often include internships or practicum experiences, which are excellent opportunities to gain hands-on experience in a science library setting. You can explore different library science programs using resources available on OpenCourser.

Specializing Further: Certifications and Advanced Degrees

Beyond the MLIS, librarians can pursue specialized certifications to enhance their expertise in specific areas. For example, certifications in data management or data curation are becoming increasingly relevant as research data services become a core part of science librarianship. Organizations like the Data Curation Network or initiatives through professional associations may offer such credentials.

Some Science Librarians hold additional advanced degrees, such as a Master's or PhD in a specific scientific discipline. While not typically required, a second Master's or a PhD can be advantageous for certain roles, particularly those involving deep subject specialization, extensive research support for faculty, or leadership positions in large research libraries.

A PhD in Information Science or a related field might be pursued by those interested in research and teaching within library and information science itself, focusing on topics relevant to scientific communication, information retrieval, or data science in a library context.

Alternative Learning Strategies

Exploring Open Educational Resources

For those exploring the field or looking to supplement formal education, a wealth of Open Educational Resources (OER) exists. These include free online courses, webinars, tutorials, articles, and guides covering various aspects of librarianship, information science, and specific scientific domains. Platforms often host relevant introductory courses, sometimes from top universities.

Leveraging OER requires self-direction and discipline but can be a cost-effective way to build foundational knowledge or acquire specific skills. Topics might range from understanding metadata standards to learning about scholarly communication trends or specific database search techniques. Many professional library associations also make some of their resources freely available.

Using platforms like OpenCourser's browse feature can help identify relevant free or low-cost learning materials across different providers. Building a portfolio of completed OER modules or projects can demonstrate initiative and relevant knowledge to potential employers or graduate programs.

Learning Through Doing: Projects and Experience

Practical experience is invaluable. Actively seeking out projects, volunteer opportunities, or internships in library or information settings can provide crucial hands-on skills. This might involve assisting with collection management tasks, helping at a reference desk, working on a digital archiving project, or supporting data curation efforts.

Creating personal projects can also demonstrate skills and passion. For instance, one could build a curated bibliography on a specific scientific topic using citation management software, develop a small database, create an online research guide using web tools, or analyze citation patterns in a specific journal using bibliometric techniques.

Documenting these projects and experiences clearly on a resume or portfolio showcases practical abilities beyond formal coursework. It demonstrates initiative and a commitment to applying learned concepts in real-world scenarios, which can be particularly helpful for career changers.

Pivoting from Related Fields

Individuals with backgrounds in related professions can successfully transition into science librarianship. Researchers (PhD students, postdocs, lab technicians) possess deep subject expertise and research skills that are highly valuable. They often need to supplement this with formal library science education (an MLIS) but bring immediate credibility in supporting research.

Professionals in data analysis, data management, IT, or scientific publishing also possess transferable skills. Understanding data lifecycles, database management, metadata, or the publishing process can be directly applicable. Again, an MLIS is usually necessary to bridge the gap into librarianship roles.

Making this pivot requires highlighting transferable skills and potentially acquiring new ones through coursework or self-study. Networking with librarians, conducting informational interviews, and gaining library-related experience (even volunteering) can ease the transition and demonstrate commitment to the new field.

For those considering a career change, remember that your existing expertise is valuable. The path may involve additional learning, but your unique background can be a significant asset in this interdisciplinary field. Grounding yourself in the requirements while exploring learning pathways is key.

Networking and Professional Development

Engaging with the professional community is a vital learning strategy. Joining library associations, such as the Special Libraries Association (SLA) with its relevant divisions, or the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) and its Science & Technology Section (STS), provides access to resources, mentorship opportunities, and job postings.

Attending conferences, workshops, and webinars (many now offered online) is crucial for staying current with trends, technologies, and best practices. These events offer formal learning sessions and informal networking opportunities to connect with experienced professionals and peers.

Participating in online forums, discussion lists, or social media groups dedicated to science librarianship or related topics allows for ongoing learning and exchange of ideas. Building a professional network provides support, advice, and potential leads throughout one's career journey.

Career Progression in Science Librarianship

Starting Out and Moving Up

Entry-level positions often carry titles like "Science Librarian," "STEM Librarian," "Engineering Librarian," or "Life Sciences Librarian," typically requiring an MLIS degree and sometimes a relevant science background. These roles usually involve a mix of reference, instruction, and collection development duties, often under the guidance of more senior librarians.

With experience, librarians can advance to roles with greater responsibility. This might involve managing a specific branch library (e.g., an engineering library), leading a team of subject librarians, or specializing in a high-demand area like research data management, scholarly communication, or bioinformatics support.

Senior roles could include titles like "Head of Science Libraries," "Associate Director for Research Services," or "Data Services Coordinator." Progression often depends on demonstrated expertise, leadership potential, contributions to the profession (like publications or presentations), and sometimes additional qualifications.

Diverse Work Environments: Academia, Industry, and Beyond

The most common setting for Science Librarians is academic libraries at universities and colleges with strong science and engineering programs. Here, the focus is on supporting teaching, learning, and research within the academic community.

However, opportunities also exist in other sectors. Corporate libraries in industries like pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, aerospace, chemicals, and technology employ science librarians to support research and development teams, competitive intelligence, and patent searching. Government agencies (e.g., NIH, NASA, EPA, DOE) also hire librarians with scientific backgrounds for their research labs and libraries.

Other potential employers include research institutes, hospitals (as medical librarians, a closely related field), museums with scientific collections, and scientific societies. The specific responsibilities and required skills can vary significantly depending on the type of institution.

Developing Leadership Capabilities

Moving into leadership positions typically requires several years of professional experience and a track record of success in core librarian roles. Developing skills in project management, budget management, strategic planning, and personnel supervision becomes increasingly important.

Leadership development can occur through taking on progressively responsible roles within the library, chairing committees, leading projects, or pursuing formal management training. Mentorship from senior librarians can provide valuable guidance.

Contributing to the broader library profession through involvement in associations, publishing research, or presenting at conferences also builds leadership credentials. Strong communication, collaboration, and advocacy skills are essential for effectively leading teams and representing library interests within the larger organization.

Branching Out: Related Career Opportunities

The skills and knowledge gained as a Science Librarian are transferable to various adjacent fields. Some librarians transition into roles focused purely on research data management or data curation, either within or outside a library setting.

Others may move into scholarly communication roles, focusing on institutional repositories, open access initiatives, or copyright advisory services. Opportunities might also exist in knowledge management, competitive intelligence, information architecture, or technical writing, particularly in science or technology-focused companies.

With additional training or experience, some might pivot towards data science or bioinformatics analysis roles, leveraging their analytical skills and subject familiarity. The blend of technical, analytical, communication, and subject-specific skills provides a versatile foundation for various information-intensive careers.

Technological Disruption in Science Librarianship

The Rise of AI in Research Discovery

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning are increasingly impacting how scientific information is discovered and accessed. AI-powered tools are being developed for literature searching, summarizing research papers, identifying trends, and even generating hypotheses. Science Librarians need to understand these tools' capabilities and limitations.

This involves evaluating AI-driven discovery platforms, teaching researchers how to use them effectively and critically, and potentially incorporating them into library services. Librarians may play a role in curating training datasets or providing feedback on the development of AI tools tailored for specific scientific domains.

While AI offers powerful new capabilities, it also raises ethical considerations regarding bias in algorithms, transparency, and the potential for misinformation. Librarians are well-positioned to help researchers navigate these complexities and promote responsible use of AI in the research process.

Understanding the philosophy and structure of science can help evaluate the outputs of AI systems.

The Open Access Revolution

The movement towards open access (OA) publishing fundamentally changes how scientific research is disseminated and funded. Science Librarians play a crucial role in navigating this complex landscape, advising researchers on OA publishing options, understanding various OA models (Gold, Green, Bronze, Diamond), and managing institutional funds for article processing charges (APCs).

They advocate for sustainable and equitable OA models and help researchers comply with funder mandates requiring open dissemination of research outputs. This involves understanding publisher agreements, copyright policies, and the use of institutional or subject repositories for archiving accepted manuscripts (Green OA).

The shift towards OA impacts collection development strategies, as libraries may redirect funds from traditional subscriptions towards supporting OA initiatives. Librarians monitor the evolving OA landscape and its implications for information access and scholarly communication workflows.

The Data Deluge: Management and Curation

The increasing volume, velocity, and variety of research data ("big data") present significant challenges and opportunities. Funder mandates increasingly require researchers to create Data Management Plans (DMPs) and share their data openly. Science Librarians are stepping into vital roles supporting Research Data Management (RDM).

This involves educating researchers on best practices for organizing, documenting (metadata), storing, and preserving data throughout the research lifecycle. Librarians may provide consultations on writing DMPs, identify appropriate data repositories, and advise on data citation and licensing.

Developing expertise in data curation – ensuring data is findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR principles) – is becoming a key skill set. This might involve understanding discipline-specific metadata standards, data formats, and preservation techniques.

This book discusses the social aspects of technology, relevant to data management infrastructure.

Building Digital Storehouses: Institutional Repositories

Institutional Repositories (IRs) serve as platforms to collect, preserve, and showcase the scholarly output of an institution, including publications, theses, and increasingly, research data. Science Librarians are often involved in managing, populating, and promoting the use of IRs.

Challenges include ensuring consistent metadata quality, managing copyright and permissions, integrating the IR with other institutional systems, and advocating for faculty participation. Technical aspects involve understanding repository software (like DSpace or Samvera), digital preservation standards, and persistent identifiers.

IRs are crucial infrastructure for supporting open access mandates and increasing the visibility and impact of institutional research. Librarians play a key role in developing policies, workflows, and outreach strategies to maximize the value and utility of these digital collections.

Global Perspectives on Science Librarianship

Variations Across Borders

While the core functions of science librarianship are similar globally, specific requirements and practices can vary. Credentialing standards differ; while the ALA-accredited MLIS is standard in North America, other regions may have different educational pathways or professional certifications for librarians.

The prevalence of specific technologies, the development of national research infrastructures (like data repositories or shared catalogs), and funding models for libraries and research can also differ significantly between countries. Understanding these regional variations is important for international students or professionals considering working abroad.

Language proficiency is often a key factor, particularly in roles requiring extensive user interaction or instruction. Familiarity with the specific scientific research landscape and publishing norms within a particular country or region is also beneficial.

Opportunities in Emerging Economies

As research capacity grows in emerging economies, so does the need for skilled information professionals, including Science Librarians. Supporting developing research infrastructures, promoting information literacy, and facilitating access to global scientific knowledge are critical needs.

Opportunities may exist in universities, government research agencies, or international organizations working to build scientific capacity. These roles might involve establishing new library services, training local staff, or adapting information management practices to local contexts and resource constraints.

Working in such environments can be highly rewarding but may also present unique challenges related to funding, technology access, and cultural differences. It often requires adaptability, resourcefulness, and strong cross-cultural communication skills.

Connecting Globally: Collaboration Models

Scientific research is inherently global, and science librarianship increasingly involves international collaboration. This can take many forms, such as participating in international library consortia for resource sharing or negotiation, contributing to global open science initiatives, or collaborating on research projects with librarians in other countries.

International conferences and professional associations provide platforms for building global networks and sharing best practices. Collaborative projects might focus on developing shared metadata standards, building federated search systems, or creating multilingual information resources.

Technology facilitates remote collaboration, allowing librarians to work together across borders on digital projects, virtual reference services, or online training initiatives. This global interconnectedness enriches the profession and enhances support for international research endeavors.

Aligning with Global Goals

The work of Science Librarians aligns with several broader global objectives, such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). By facilitating access to scientific information and supporting research, they contribute to advancements in health (SDG 3), education (SDG 4), innovation (SDG 9), climate action (SDG 13), and more.

Promoting open science and equitable access to information supports the goal of reducing inequalities (SDG 10). Supporting research data management contributes to building resilient infrastructure and fostering innovation.

Framing library services within the context of these global goals can help advocate for resources and demonstrate the broader societal impact of science librarianship. It highlights the role of information access as a catalyst for positive global change.

Frequently Asked Questions (Career Focus)

What are typical salary expectations?

Salaries for Science Librarians vary based on factors like geographic location, type of institution (academic, corporate, government), years of experience, specific responsibilities, and educational background (e.g., presence of a second master's or PhD). Academic library salaries often depend on institutional rank (if applicable) and funding levels.

According to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the median annual wage for librarians and media collections specialists (a category including science librarians) was $64,370 in May 2023. However, specialized roles or positions in high-cost-of-living areas or the private sector may offer higher compensation. Professional associations like the ALA or SLA sometimes publish more detailed salary surveys.

Entry-level salaries will typically be lower, while senior management or highly specialized roles command higher pay. Researching salary ranges for specific types of positions and locations using resources like BLS data, association surveys, and job postings is recommended.

Is remote work common?

The feasibility of remote work for Science Librarians varies. Some tasks, like online instruction, virtual reference consultations, collection analysis, database searching, and managing electronic resources, can often be done remotely. This has led to an increase in hybrid or fully remote positions, particularly since 2020.

However, many roles still require an on-site presence for in-person instruction, physical collection management, face-to-face consultations, attending departmental meetings, or managing library spaces. The extent of remote work often depends on the specific institution's policies, the nature of the role, and the user community's needs.

Job postings usually specify whether a position is remote, hybrid, or fully on-site. While remote opportunities exist and may be growing, many positions, especially in traditional academic settings, still involve significant on-campus responsibilities.

What is the long-term outlook for this career?

The overall employment of librarians is projected by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics to grow about 3 percent from 2022 to 2032, which is about average for all occupations. However, the outlook specifically for Science Librarians may be more nuanced.

Demand is likely to remain steady or potentially grow in areas requiring specialized skills, such as research data management, bioinformatics support, scholarly communication, and digital curation, driven by the increasing complexity of scientific research and data. Librarians who adapt to technological changes and develop expertise in these high-demand areas will likely have better prospects.

Budget constraints in academic and public institutions can impact hiring. However, the fundamental need for professionals who can navigate, organize, and teach others how to use complex scientific information effectively persists. Career longevity often depends on continuous learning and adapting skills to meet evolving research and information needs.

How can I transition from a research background?

Transitioning from a lab research background (e.g., as a PhD student, postdoc, or research scientist) into science librarianship is a common and often successful path. Your subject expertise and understanding of the research process are major assets. The key step is usually acquiring the professional library qualification, typically an ALA-accredited MLIS degree.

During your MLIS program, focus on coursework relevant to academic or special libraries, science librarianship, data management, and information technology. Seek internships or volunteer opportunities in a science or academic library to gain practical experience and bridge the gap between research and library work.

Highlight your transferable skills on your resume: research methodologies, data analysis, technical writing, project management, and subject expertise. Network with science librarians through informational interviews and professional associations. Be prepared to articulate why you want to move from bench science to supporting research through librarianship.

This transition requires commitment, but your research background provides a strong foundation. Frame your experience as a unique strength for understanding and serving the needs of the scientific community.

Do science librarians write grants?

While not typically the primary grant writers for scientific research projects, Science Librarians may be involved in grant-related activities in several ways. They often assist researchers in finding relevant funding opportunities using specialized databases and resources.

Librarians, especially those specializing in research data management, may contribute sections to grant proposals, particularly the Data Management Plan (DMP), which is now required by many funding agencies. They can advise on data standards, repositories, and preservation strategies outlined in the plan.

Furthermore, librarians themselves may write grants to secure funding for library projects, new resources, technology initiatives, or professional development opportunities. Grant writing skills can therefore be a valuable asset for career advancement within librarianship.

Why join professional associations?

Joining professional associations like the Special Libraries Association (SLA), the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) – particularly its Science & Technology Section (STS) – or discipline-specific information groups offers numerous benefits. These organizations provide access to continuing education opportunities (webinars, workshops, conferences) essential for staying current.

Associations offer valuable networking opportunities, connecting you with peers and mentors who can offer advice, share experiences, and potentially lead to collaborations or job opportunities. They often host job boards specifically for library and information professionals.

Membership typically includes subscriptions to professional journals and newsletters, keeping you informed about trends, research, and best practices in the field. Participating in association committees or leadership roles can enhance your skills and professional visibility. These communities are vital for career growth and staying engaged in the evolving field of science librarianship.

Helpful Resources

Exploring the field further? Here are some key organizations and resources:

- Special Libraries Association (SLA): An international association for information professionals working in special libraries, including many science and technology settings. (www.sla.org)

- Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL): A division of the American Library Association focused on academic libraries. Its Science & Technology Section (STS) is particularly relevant. (www.ala.org/acrl/)

- Medical Library Association (MLA): For those interested in health sciences librarianship, a closely related field. (www.mlanet.org)

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS): Provides occupational outlook and salary information for librarians. (www.bls.gov/ooh/education-training-and-library/librarians.htm)

- OpenCourser: Explore courses related to library science, data management, specific scientific fields, and communication skills. Use the "Save to list" feature to curate your own learning path.

Embarking on a career as a Science Librarian means entering a field dedicated to fostering scientific discovery and knowledge. It requires a unique blend of scientific literacy, technical skill, and a service-oriented mindset. Whether you are coming directly from academia, transitioning from research, or exploring options, the path involves continuous learning and adaptation in an ever-evolving information landscape. It offers the rewarding opportunity to support and engage with the forefront of science and technology.