Survey Design

Survey Design

Survey design is the systematic process of creating, testing, and implementing questionnaires to gather information from a specific group of individuals. It involves much more than simply writing questions; it encompasses defining objectives, selecting appropriate methods, crafting clear and unbiased questions, determining the right people to ask (sampling), and planning for data collection and analysis. At its core, survey design aims to produce accurate, reliable, and meaningful data that can answer research questions, inform business decisions, or shape public policy.

Understanding survey design unlocks the ability to systematically gather insights about attitudes, opinions, behaviors, and characteristics of populations large and small. It's a field that blends scientific rigor with careful communication, requiring both analytical thinking and an understanding of human psychology. Whether exploring customer satisfaction, public opinion on social issues, or the prevalence of health behaviors, well-designed surveys are indispensable tools for generating knowledge and guiding action in countless domains.

Introduction to Survey Design

What is Survey Design?

Survey design refers to the comprehensive process of planning and creating a survey to achieve specific research goals. This process starts with clearly defining the information needed and the population from which it should be gathered. It involves critical decisions about the type of survey (e.g., online, phone, mail), the way questions are worded and structured, the sequence of questions, and the visual layout of the questionnaire.

The scope extends beyond just the questionnaire itself. It includes developing a sampling strategy to ensure the respondents accurately represent the target population, planning the logistics of data collection, considering ethical implications like respondent privacy and informed consent, and anticipating how the collected data will eventually be analyzed. Effective survey design aims to maximize the quality of data by minimizing potential errors, such as those arising from ambiguous questions, biased sampling, or low response rates.

Ultimately, survey design is a foundational element of quantitative and qualitative research across many fields. It provides a structured way to collect standardized information, allowing for systematic comparison and analysis. A thoughtfully designed survey yields data that is not only relevant to the research questions but also trustworthy and actionable.

A Brief History and Key Developments

While informal information gathering has existed for millennia, modern survey research traces its roots to the social reformers and statisticians of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Early social surveys, like Charles Booth's studies of poverty in London, aimed to document social conditions systematically. The development of probability sampling techniques in the 1930s by figures like Jerzy Neyman was a major milestone, providing a scientific basis for generalizing findings from a sample to a larger population.

The mid-20th century saw the rise of large-scale public opinion polling, driven by organizations like Gallup and advancements in telephone interviewing. Concurrently, psychological research contributed significantly to understanding how respondents interpret and answer questions, leading to improved questionnaire design principles. The advent of computers revolutionized data processing and analysis, making larger and more complex surveys feasible.

More recently, the internet and mobile technology have dramatically changed the landscape of survey design. Online surveys offer speed, cost-effectiveness, and new ways to present questions (e.g., interactive elements), while also introducing new challenges like sampling biases related to internet access and the proliferation of low-quality survey platforms. Today, survey design continues to evolve, integrating insights from data science, user experience design, and behavioral economics to adapt to a changing technological and social environment.

Why Surveys Matter: Roles in Research, Business, and Policy

Surveys are fundamental tools across a wide spectrum of activities. In academic research, they are used extensively in fields like social sciences, psychology, public health, and education to understand attitudes, behaviors, and social trends. Researchers rely on surveys to test hypotheses, measure the prevalence of phenomena, and track changes over time.

In the business world, survey design is crucial for market research, customer satisfaction measurement, product development, and employee engagement studies. Companies use survey data to understand consumer preferences, evaluate marketing campaigns, identify areas for service improvement, and gauge workplace morale. These insights directly inform strategic decisions, product launches, and operational adjustments.

Governments and non-profit organizations heavily depend on surveys for policy-making and program evaluation. National statistical agencies conduct large-scale surveys (like the census or labor force surveys) to provide essential data on population demographics, economic activity, and social conditions. Surveys are also vital for assessing public needs, evaluating the impact of social programs, and monitoring public health trends, providing evidence to guide resource allocation and policy development.

Clearing Up Common Misconceptions

A frequent misconception is that designing a survey is easy – just write down some questions and send them out. In reality, creating a high-quality survey requires careful planning and expertise. Poorly worded questions, biased samples, or inappropriate methods can lead to misleading or entirely incorrect conclusions. Every step, from defining objectives to analyzing data, requires careful consideration to minimize error.

Another misunderstanding is that larger sample sizes always equate to better surveys. While sample size is important for statistical power and precision (reducing the margin of error), the representativeness of the sample is often more critical. A large but biased sample (one that doesn't accurately reflect the target population) can be less informative than a smaller, carefully selected representative sample.

Finally, some believe surveys only capture superficial opinions. While surveys are excellent for measuring attitudes and reported behaviors, well-designed questionnaires can delve into complex topics. Using sophisticated scaling techniques, indirect questioning, and careful question sequencing, researchers can gather nuanced data. However, it's also true that surveys rely on self-reporting, which can be subject to social desirability bias or recall errors, limitations that designers must acknowledge and attempt to mitigate.

Core Principles of Effective Survey Design

Ensuring Validity and Reliability

Validity and reliability are the cornerstones of measurement quality in survey design. Reliability refers to the consistency of a measurement. If a survey question is reliable, it should yield similar results if administered multiple times under the same conditions to the same respondents (assuming the underlying trait hasn't changed). Think of it like a bathroom scale: a reliable scale shows the same weight each time you step on it consecutively.

Validity, on the other hand, refers to the accuracy of a measurement – does the question actually measure the concept it's intended to measure? Our reliable scale might consistently show a weight that is 5 pounds too high; it's reliable but not valid. In survey terms, a question might reliably measure something, but not the specific construct (e.g., job satisfaction, brand loyalty) the researcher is interested in. Ensuring validity involves careful conceptualization, clear question wording, and often, comparing survey results against other, independent measures of the same concept.

Achieving both reliability and validity requires meticulous attention during questionnaire development. Ambiguous wording, complex sentence structures, or confusing response options can undermine both. Pilot testing questions with members of the target audience is crucial for identifying potential issues with clarity and interpretation, helping to refine questions until they are both consistently understood (reliable) and accurately capture the intended meaning (valid).

Writing Clear and Neutral Questions

The way a question is worded can significantly influence the answers received. A core principle is to strive for clarity and neutrality. Clear questions use simple, direct language and avoid jargon, technical terms, or abbreviations that might not be universally understood by the target audience. Each question should focus on a single topic or idea; "double-barreled" questions that ask about multiple things at once (e.g., "Was the service fast and friendly?") are problematic because a respondent might agree with one part but not the other.

Neutrality means phrasing questions in a way that does not suggest a preferred or socially desirable answer. Leading questions (e.g., "Don't you agree that...") steer respondents toward a particular response and introduce bias. Similarly, loaded questions use emotionally charged language that can sway answers. The goal is to allow respondents to express their genuine views without feeling pressured or guided by the question's phrasing.

Crafting effective questions often involves multiple drafts and revisions. Considering the cognitive processes respondents go through – understanding the question, retrieving relevant information, forming a judgment, and selecting a response – helps anticipate potential difficulties. Pre-testing questions, even informally by asking colleagues or potential respondents to "think aloud" as they answer, is invaluable for identifying ambiguity or bias.

The Importance of Representative Sampling

Unless the goal is to survey every single member of a target population (a census), researchers rely on sampling – selecting a subset of individuals to participate. The primary goal of most sampling strategies in survey design is to achieve representativeness, meaning the characteristics of the sample closely mirror the characteristics of the larger population of interest.

Why is representativeness so critical? Because it allows researchers to generalize the findings from the sample back to the entire population with a known degree of confidence. If a sample is not representative (e.g., it over-represents younger people or under-represents rural residents compared to the overall population), any conclusions drawn may be biased and inaccurate when applied to the population as a whole.

Achieving representativeness typically involves probability sampling methods, where every member of the target population has a known, non-zero chance of being selected. Techniques like simple random sampling, stratified sampling, or cluster sampling are designed to minimize selection bias. Non-probability methods (like convenience sampling or snowball sampling) are sometimes used, particularly in exploratory research or when probability sampling is infeasible, but they come with significant limitations regarding generalizability.

Pilot Testing: Refining Before Launching

Pilot testing, also known as pre-testing, is a crucial step where a draft version of the survey is administered to a small group of individuals similar to the target population before the main launch. This is essentially a dress rehearsal that helps identify problems with the questionnaire, the sampling approach, or the data collection procedures.

During pilot testing, researchers look for issues such as confusing or ambiguous question wording, problems with question flow or sequence, technical glitches in online surveys, difficulties respondents have with specific tasks, and estimates of how long the survey takes to complete. Feedback can be gathered through observation, follow-up interviews with pilot participants ("cognitive interviewing"), or analysis of the pilot data itself (e.g., looking for questions with high rates of missing responses or unexpected answer patterns).

The insights gained from pilot testing are invaluable for refining the survey instrument and procedures. It allows designers to fix problematic questions, adjust the layout, clarify instructions, and troubleshoot technical issues. Skipping this step is risky, as undetected flaws in the survey can compromise the quality and validity of the data collected in the full study. Iterative refinement, based on pilot test feedback, significantly increases the likelihood of a successful survey implementation.

Types of Surveys and Their Applications

Choosing the Right Time Frame: Cross-Sectional vs. Longitudinal

Surveys can be categorized based on when data is collected relative to the population. Cross-sectional surveys collect data from a sample at a single point in time. They provide a "snapshot" of the population's characteristics, attitudes, or behaviors at that moment. For example, a survey measuring public opinion on a current event or assessing the prevalence of a specific health condition in a community would typically be cross-sectional.

Longitudinal surveys, in contrast, involve collecting data from the same individuals (or samples from the same population) repeatedly over an extended period. This allows researchers to track changes, trends, and developments over time. There are different types of longitudinal designs, including panel studies (following the exact same individuals) and cohort studies (following individuals who share a common characteristic, like birth year). Longitudinal surveys are powerful for studying developmental processes, the effects of interventions, or shifts in attitudes and behaviors.

The choice between cross-sectional and longitudinal designs depends entirely on the research question. Cross-sectional surveys are generally less expensive and faster to conduct but cannot establish cause-and-effect relationships or track individual changes. Longitudinal studies provide richer insights into dynamic processes but are more complex, costly, and susceptible to issues like participant attrition (drop-out) over time.

Defining the Goal: Descriptive vs. Explanatory Surveys

Surveys can also be classified by their primary objective. Descriptive surveys aim to describe the characteristics of a population or phenomenon. They focus on answering "what," "who," "where," and "when" questions. Examples include surveys determining the demographic makeup of a customer base, measuring the frequency of certain behaviors (like voting or recycling), or gauging public awareness of a health campaign.

Explanatory surveys go beyond description to explore the relationships between variables and attempt to answer "why" questions. They aim to test hypotheses and understand the potential causes or predictors of certain attitudes or behaviors. For instance, an explanatory survey might investigate the factors influencing job satisfaction, examine the relationship between social media use and self-esteem, or test whether exposure to a specific advertisement impacts purchase intent.

While descriptive surveys provide valuable foundational information, explanatory surveys often require more complex designs and analytical techniques (like regression analysis) to disentangle relationships between variables. Many surveys incorporate both descriptive and explanatory elements, first describing a situation and then exploring potential underlying factors.

Selecting the Mode: Online, Phone, In-Person, and More

The mode refers to the method used to administer the survey and collect responses. Common modes include online surveys (distributed via email links or websites), telephone interviews (conducted by live interviewers or automated systems), face-to-face interviews (conducted in person at homes, workplaces, or public locations), and mail surveys (paper questionnaires sent and returned via postal service).

Each mode has distinct advantages and disadvantages regarding cost, speed, sampling capabilities, data quality, and the types of questions that can be asked. Online surveys are often cost-effective and quick but can suffer from sampling biases related to internet access and potentially lower response rates. Telephone surveys allow for clarification but are increasingly challenged by call screening and declining landline use. Face-to-face interviews often yield high response rates and allow for complex questions and observation but are expensive and time-consuming. Mail surveys can reach populations without internet access but tend to have slower response times.

Hybrid or mixed-mode approaches, which combine different methods (e.g., initial contact by mail with an option to complete online), are increasingly used to leverage the strengths of each mode and mitigate their weaknesses. The choice of mode(s) should be driven by the research objectives, the target population's characteristics, the available budget, and the desired level of data quality.

These courses offer insights into quantitative research methods and specific tools used in survey administration.

Specialized Applications: Market Research, Public Health, and Beyond

Survey design principles are applied across numerous specialized fields. In market research, surveys are essential for understanding consumer behavior, segmenting markets, testing product concepts, measuring brand perception, and assessing advertising effectiveness. Techniques like conjoint analysis, often implemented via surveys, help businesses understand how consumers value different product features.

In public health, surveys are critical for epidemiological surveillance (monitoring disease prevalence and risk factors), assessing health behaviors (like smoking or diet), evaluating health interventions, and understanding access to healthcare. Specialized surveys like the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) in the US provide vital data for health policy. Designing surveys for sensitive health topics requires particular attention to ethics and question wording.

Other fields rely heavily on surveys as well. Political scientists use election polling and public opinion surveys. Sociologists study social trends, attitudes, and inequalities. Program evaluators use surveys to assess the impact and effectiveness of social programs and interventions. Educational researchers survey students, teachers, and administrators. The versatility of survey methods makes them applicable wherever systematic data collection from individuals is needed.

These resources delve into market research applications and specialized survey contexts like program evaluation in specific settings.

Questionnaire Design Best Practices

Avoiding Pitfalls: Leading and Double-Barreled Questions

Crafting effective survey questions requires vigilance against common errors that can bias responses or confuse participants. Leading questions subtly prompt respondents towards a particular answer. For example, instead of asking "How satisfied were you with our service?", a leading version might be "How satisfied were you with our excellent service?". The inclusion of "excellent" suggests a positive response is expected. Neutral wording is essential: "Please rate your satisfaction with our service."

Double-barreled questions combine two distinct issues into one, making it impossible for respondents to answer accurately if they feel differently about each part. An example is: "Do you think the company should increase salaries and reduce working hours?" Someone might support one change but not the other. Such questions must be split into separate, single-issue questions: "Do you think the company should increase salaries?" and "Do you think the company should reduce working hours?".

Identifying and correcting these types of flawed questions is a fundamental aspect of good questionnaire design. Careful review, ideally by multiple people, and pilot testing are the best ways to catch these errors before the survey is widely distributed.

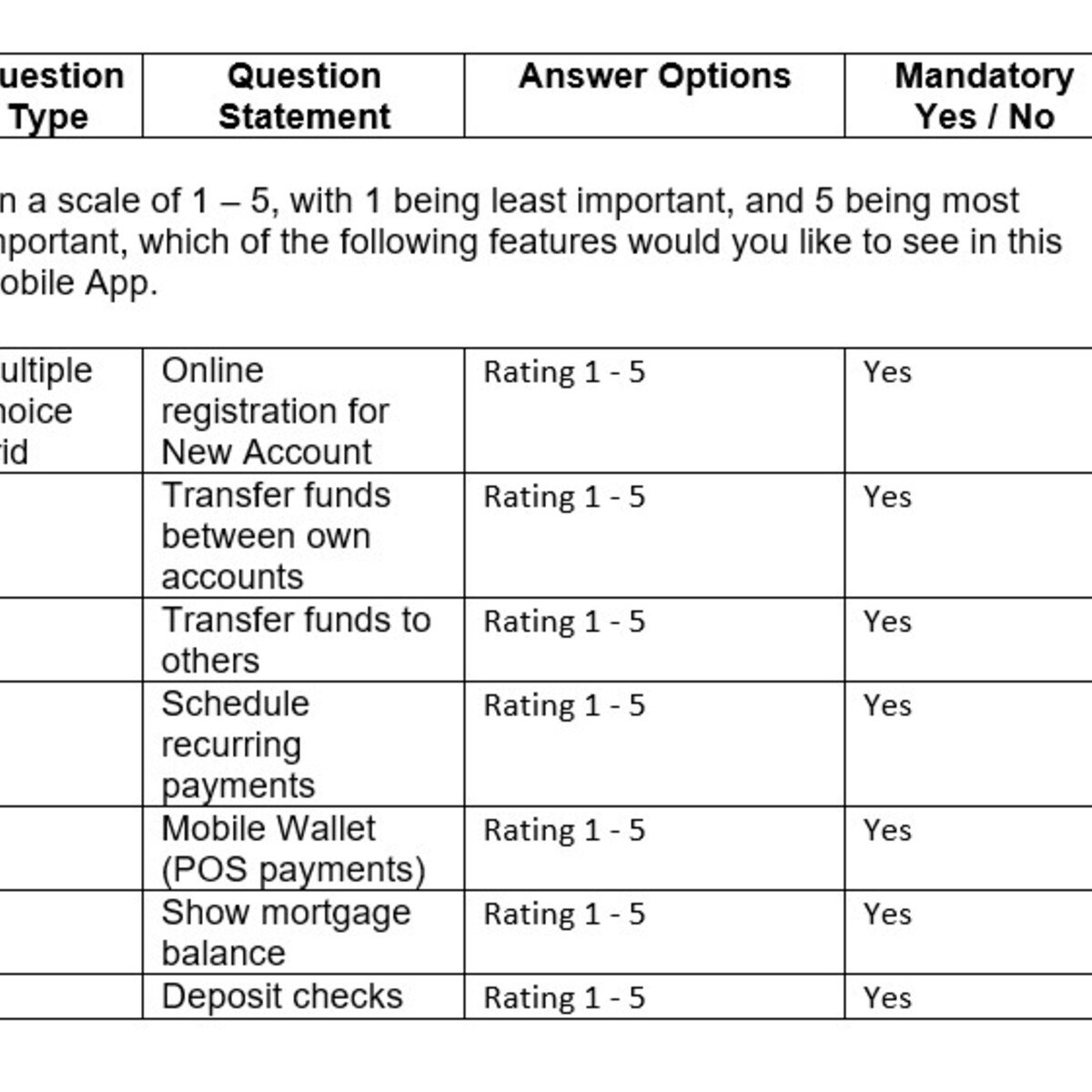

Measuring Intensity: Scaling Techniques

Often, surveys need to measure not just whether someone agrees or disagrees, but the intensity of their feeling or opinion. Scaling techniques provide standardized ways to capture these nuances. The Likert scale is perhaps the most common, asking respondents to rate their agreement with a statement on a symmetric scale (e.g., Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Neutral, Agree, Strongly Agree).

Another popular technique is the semantic differential scale, which asks respondents to rate a concept on a scale anchored by bipolar adjectives (e.g., rating a brand on a scale from "Unreliable" to "Reliable", or "Old-fashioned" to "Modern"). Other scales include frequency scales (Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Always) or numerical rating scales (e.g., rate satisfaction on a scale of 1 to 10).

The choice of scale depends on the concept being measured and the type of data needed. Important considerations include the number of scale points (e.g., 5-point vs. 7-point Likert), whether to include a neutral midpoint, and how to label the scale points clearly. Consistent use of well-designed scales enhances the comparability and interpretability of survey data.

This course delves into the fundamentals of designing questionnaires, including question construction and evaluation.

Managing Flow: Order Effects and Cognitive Load

The order in which questions are presented can influence how respondents answer subsequent questions, a phenomenon known as order effects. For example, asking about overall life satisfaction after asking about specific recent negative events might result in a lower satisfaction rating than if the general question came first. Survey designers must carefully consider the logical flow of questions to minimize unintended influences.

Generally, it's advisable to start with simple, engaging, and non-sensitive questions to build rapport and ease respondents into the survey. More complex or sensitive questions are often placed later. Questions should be grouped logically by topic. Transitions between different sections should be clear. Randomizing the order of certain question blocks or response options can sometimes help mitigate order effects, particularly in online surveys.

Cognitive load refers to the mental effort required for respondents to understand and answer questions. Surveys that are too long, contain overly complex questions, or require difficult recall tasks can overwhelm respondents, leading to fatigue, frustration, and lower-quality data (e.g., satisficing, where respondents give minimal acceptable answers rather than thoughtful ones). Designers must balance the need for comprehensive data with respect for respondents' time and cognitive capacity, keeping questionnaires concise and questions as straightforward as possible.

Ensuring Access: Inclusive Language and Accessibility

Surveys should be designed to be understood and answered by all members of the intended target population. This includes using inclusive language that avoids jargon, slang, or culturally specific idioms that might not be universally understood. Language should be respectful and avoid stereotypes or assumptions about respondents' backgrounds, identities, or experiences.

When surveying diverse populations, careful consideration must be given to demographic questions. Offer appropriate response options, include "prefer not to answer" or "other (please specify)" choices, and only ask demographic questions that are directly relevant to the research goals. Ensure questions about gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, and disability are phrased respectfully and align with current best practices.

Accessibility is also crucial, especially for online surveys. This means designing surveys that can be navigated and completed by people using assistive technologies like screen readers. This involves using proper HTML structure, providing text alternatives for images, ensuring sufficient color contrast, and allowing for keyboard navigation. Following web accessibility guidelines (like WCAG) helps ensure that the survey is usable by the widest possible audience.

These books offer practical guidance on the research process, which includes careful questionnaire design.

Sampling Strategies in Survey Design

Choosing Participants: Probability vs. Non-Probability Sampling

A critical decision in survey design is how to select the participants (the sample) from the larger population of interest. Sampling methods fall into two broad categories: probability sampling and non-probability sampling. Probability sampling techniques ensure that every individual in the target population has a known, non-zero probability of being included in the sample. This randomness is key to reducing selection bias and allows researchers to make statistical inferences about the population based on the sample data.

Common probability methods include Simple Random Sampling (SRS), where everyone has an equal chance of selection; Stratified Sampling, where the population is divided into subgroups (strata) and random samples are drawn from each stratum; and Cluster Sampling, where the population is divided into clusters (like geographic areas) and a random sample of clusters is selected, with individuals then sampled within those clusters. These methods require a sampling frame – a list of all individuals in the population – which can sometimes be difficult or impossible to obtain.

Non-probability sampling methods do not involve random selection, meaning some individuals have no chance of being selected, or their probability of selection is unknown. Examples include Convenience Sampling (selecting easily accessible individuals), Quota Sampling (selecting individuals to meet predefined quotas for certain characteristics), and Snowball Sampling (asking initial participants to refer others). While often cheaper and easier to implement, non-probability samples generally do not allow for statistical generalization to the broader population because the risk of selection bias is high.

How Many is Enough? Sample Size and Margin of Error

A common question is: "How large does my sample need to be?" The answer depends on several factors, including the desired level of precision, the variability within the population, the size of the population (though this matters less for very large populations), and the specific analysis planned. Larger samples generally lead to greater precision and statistical power.

Precision is often expressed in terms of the margin of error, which quantifies the random sampling error associated with a survey result. For example, a poll result might be reported as "45% ± 3%," meaning the true population value is likely between 42% and 48%. A smaller margin of error (higher precision) requires a larger sample size. Calculators and formulas are available to estimate the required sample size based on the desired margin of error, confidence level (typically 95%), and estimated population variability.

It's crucial to remember that sample size calculations address only random sampling error. They do not account for potential biases arising from poor question design, non-response, or inadequate sampling frames. A large sample size cannot compensate for a fundamentally flawed survey design or a non-representative sampling method.

Dealing with Missing Voices: Non-Response Bias

Non-response occurs when selected individuals cannot be contacted or refuse to participate in the survey. If the people who respond are systematically different from those who do not respond regarding the characteristics or opinions being measured, non-response bias occurs. This bias threatens the representativeness of the sample and can lead to inaccurate conclusions about the population.

For example, if a survey about political attitudes has a lower response rate among younger adults, the results might overstate the prevalence of opinions held by older adults. Minimizing non-response is a major goal in survey implementation. Strategies include sending advance notifications, using multiple contact attempts across different modes (e.g., email, phone), offering incentives (where appropriate and ethical), keeping questionnaires concise and engaging, and clearly communicating the survey's purpose and importance.

After data collection, researchers often analyze response patterns to assess potential non-response bias. This might involve comparing the demographic characteristics of respondents to known population figures or comparing early respondents to late respondents (as late respondents may share characteristics with non-respondents). Statistical techniques like weighting can sometimes be used to adjust the sample data to better match population characteristics, partially mitigating the impact of non-response bias, although they cannot fully eliminate it.

Reaching Everyone: Surveying Special Populations

Some research requires surveying specific "special populations" that may be difficult to reach or enumerate through standard sampling methods. These might include groups like homeless individuals, undocumented immigrants, users of illicit drugs, members of specific ethnic minorities, or individuals with rare diseases. Standard sampling frames (like telephone directories or voter lists) often do not adequately cover these groups.

Reaching such populations often requires specialized sampling techniques. Venue-based sampling involves recruiting participants at locations frequented by the target group. Respondent-Driven Sampling (RDS) is a network-based approach similar to snowball sampling but incorporates mathematical modeling to adjust for non-random recruitment patterns. Targeted outreach through community organizations or leaders trusted by the population can also be effective.

Designing surveys for special populations also requires careful consideration of cultural sensitivity, language barriers, trust, and potential risks to participants. Building rapport, ensuring confidentiality, and adapting methods to the specific context are crucial for successful data collection with hard-to-reach groups.

This course provides a framework for understanding data collection and analysis, including sampling considerations.

Data Collection and Management

Leveraging Technology: Digital Tools for Distribution

The digital age has transformed survey distribution and data collection. Numerous online platforms and software tools facilitate the creation, distribution, and management of web-based surveys. Tools like Qualtrics, SurveyMonkey, Google Forms, Microsoft Forms, and Zoho Forms offer features for designing questionnaires with various question types, distributing surveys via links or email invitations, tracking responses in real-time, and basic data analysis.

These digital tools offer significant advantages in terms of speed, cost-efficiency, and reach compared to traditional paper-based methods. They can automate reminders to non-respondents, implement complex skip logic (where answers to one question determine which subsequent questions are shown), and randomize question order to mitigate bias. Many platforms also offer features optimized for mobile devices, catering to the increasing number of respondents who take surveys on smartphones or tablets.

However, reliance on digital tools also requires careful consideration of potential drawbacks. Ensuring data security and respondent privacy on third-party platforms is paramount. Sampling bias remains a concern, as access and comfort with technology vary across populations. Designing user-friendly interfaces that work across different devices and browsers is also essential for a positive respondent experience.

These courses provide hands-on experience with specific digital survey tools.

Maintaining Accuracy: Quality Control During Collection

Ensuring data quality doesn't end once the survey is designed; it continues throughout the data collection phase. Implementing quality control measures helps identify and address potential problems as they arise. For online surveys, this might involve monitoring response rates, tracking dropout points (where respondents abandon the survey), and checking for suspicious response patterns (e.g., extremely fast completion times, identical answers to all questions).

In interviewer-administered surveys (phone or face-to-face), quality control involves thorough interviewer training, monitoring interviewer performance (e.g., through call recordings or observations), and conducting back-checks (re-contacting a subset of respondents to verify their answers). Clear protocols for handling ambiguous responses or respondent questions are also necessary.

Real-time monitoring allows for quick adjustments if problems are detected. For instance, if a particular question has a very high rate of missing data or "don't know" responses, it might indicate confusing wording that needs clarification. Promptly addressing technical glitches or procedural issues helps maintain the integrity of the data collection process.

Protecting Participants: Anonymization and Secure Storage

Ethical survey practice requires safeguarding respondent data. Anonymization involves removing any personally identifiable information (PII) – such as names, addresses, email addresses, or unique identification numbers – from the survey responses before analysis or sharing. This protects respondent confidentiality and reduces the risk associated with data breaches.

In some cases, full anonymization is not possible or desirable (e.g., in longitudinal studies where individuals need to be re-contacted). In such situations, pseudonymization (replacing identifiers with codes) and strict data security measures are employed. This includes storing identifying information separately from survey responses, using encryption, controlling access to the data, and establishing clear data retention and destruction policies.

Researchers must comply with relevant data privacy regulations (like GDPR in Europe or HIPAA for health information in the US) and institutional review board (IRB) requirements regarding data security and confidentiality. Secure storage practices, both for digital and physical data, are essential throughout the research lifecycle.

Navigating the Field: Common Implementation Pitfalls

Even well-designed surveys can encounter problems during field implementation. A common pitfall is underestimating the resources needed for data collection, including time, budget, and personnel, especially for interviewer-administered or complex surveys. Inadequate training for interviewers can lead to inconsistent administration and increased measurement error.

Poor communication with potential respondents – unclear invitations, lack of follow-up, or failure to convey the survey's value – can contribute to low response rates. Technical problems with online survey platforms, such as compatibility issues across different browsers or devices, can frustrate respondents and lead to dropouts.

Failure to adapt procedures to unexpected circumstances (e.g., encountering language barriers not initially anticipated, changes in the target population's availability) can also derail data collection. Careful planning, robust quality control, flexibility, and proactive problem-solving are key to navigating these potential challenges and ensuring successful field implementation.

This course covers practical aspects relevant to implementing data collection, including interview techniques.

Ethical Considerations in Survey Design

Respecting Autonomy: The Informed Consent Process

A cornerstone of ethical research involving human participants is informed consent. This means potential respondents must be provided with sufficient information about the survey to make a voluntary decision about whether or not to participate. This information typically includes the purpose of the research, what participation involves (e.g., types of questions, estimated time commitment), potential risks and benefits, how confidentiality will be protected, and who to contact with questions.

Consent must be voluntary, meaning individuals should not feel coerced or unduly pressured into participating. They must also be informed that they can withdraw from the survey at any time without penalty. For online surveys, consent is often obtained by presenting this information on the first page and requiring participants to click a button to indicate agreement before proceeding. For minors or individuals with diminished capacity, consent may need to be obtained from a parent or legal guardian, often along with the participant's assent.

The process ensures that individuals understand what they are agreeing to and participate based on their own free will, respecting their autonomy. Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) or ethics committees typically review survey protocols, including consent procedures, to ensure they meet ethical standards.

Navigating Regulations: Privacy Rules (GDPR, HIPAA)

Survey researchers must be aware of and comply with relevant data privacy regulations, which vary by jurisdiction and the type of data being collected. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union, for example, sets strict rules for collecting, processing, and storing personal data of EU residents, emphasizing transparency, data minimization, and individual rights like the right to access or erase one's data.

In the United States, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) governs the privacy and security of protected health information (PHI). Researchers collecting health-related data covered by HIPAA must implement specific safeguards and often require explicit authorization from participants beyond standard informed consent.

Understanding these regulations is crucial to avoid legal penalties and maintain public trust. Researchers need to ensure their data handling practices – from collection to storage and sharing – align with applicable legal requirements. This often involves consulting with institutional experts or legal counsel, particularly when dealing with sensitive data or international populations.

This book touches upon health and environmental research, areas often subject to stringent privacy regulations.

Handling Sensitive Topics with Care

Surveys often explore sensitive topics, such as personal finances, health conditions, illegal behaviors, trauma, or opinions on controversial issues. Asking questions about such topics requires particular care to minimize potential distress or harm to respondents and to maximize truthful reporting.

Strategies include careful question wording to be non-judgmental, placing sensitive questions later in the survey after rapport has been established, using normalizing statements (e.g., "Many people find it difficult to..."), and ensuring absolute clarity about confidentiality protections. Offering "prefer not to answer" options is essential.

Researchers must also consider potential risks beyond the survey interaction itself. For example, could participation expose individuals to social stigma or legal jeopardy if confidentiality were breached? Providing resources or referrals (e.g., contact information for support services) may be appropriate when dealing with particularly difficult topics like mental health or domestic violence. The potential benefits of collecting sensitive data must always be weighed against the potential risks to participants.

Building Trust Through Transparency

Transparency is fundamental to ethical survey practice. Researchers should be clear and honest with participants about the purpose of the survey, who is sponsoring the research, how the data will be used, and how their privacy will be protected. Deception should be avoided unless absolutely necessary for the research question and justified to an ethics committee, and even then, debriefing is usually required.

Transparency extends to reporting results. Researchers have an ethical obligation to report their methods and findings accurately and completely, including limitations of the study (e.g., low response rate, potential biases). Selectively reporting only findings that support a particular viewpoint is unethical.

Being transparent builds trust with participants and the public. When individuals understand why research is being done and how their contribution matters, they are more likely to participate thoughtfully. Openness about methods allows the scientific community and other stakeholders to evaluate the quality and credibility of the research.

Analyzing and Interpreting Survey Data

Choosing the Right Lens: Quantitative vs. Qualitative Analysis

Once survey data is collected, the next step is analysis. The approach depends largely on the type of data gathered. Quantitative analysis deals with numerical data, typically from closed-ended questions (e.g., rating scales, multiple-choice). It involves statistical methods to summarize data (e.g., calculating percentages, means, medians) and test relationships between variables (e.g., correlations, t-tests, regression analysis). The goal is often to quantify patterns, measure associations, and generalize findings from the sample to the population.

Qualitative analysis focuses on non-numerical data, usually from open-ended questions where respondents provide textual answers in their own words. Techniques like thematic analysis or content analysis are used to identify recurring themes, patterns, and insights within the text. Qualitative analysis provides rich, in-depth understanding of respondents' perspectives, experiences, and reasoning, often complementing quantitative findings by explaining the "why" behind the numbers.

Many surveys incorporate both closed-ended and open-ended questions, allowing for a mixed-methods approach that combines the strengths of both quantitative and qualitative analysis to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the research topic.

Tools of the Trade: Analysis Software

Analyzing survey data, especially large datasets, typically requires specialized software. For quantitative analysis, common choices include statistical packages like SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences), SAS, Stata, and the open-source language R. These programs offer a wide range of tools for data cleaning, manipulation, descriptive statistics, inferential tests, and complex modeling.

For qualitative analysis of open-ended responses, researchers often use Computer-Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS) such as NVivo, MAXQDA, or ATLAS.ti. These tools help researchers organize textual data, assign codes to segments of text, identify patterns and themes, and build theoretical models based on the data. While the software facilitates management and analysis, the intellectual work of interpretation still rests with the researcher.

Spreadsheet software like Microsoft Excel or Google Sheets can also be used for basic data management, descriptive statistics, and creating simple charts, particularly for smaller datasets or preliminary analysis.

These courses provide introductions to data analysis frameworks and specific tools used in data collection and analysis.

Adjusting the Scales: Weighting and Bias Correction

Even with careful sampling, the final sample of respondents might not perfectly mirror the target population demographics due to random chance or non-response bias. If certain groups are over- or under-represented, the raw survey results might be skewed. Weighting is a statistical technique used to adjust the data to correct for these discrepancies.

Post-stratification weighting involves adjusting the influence (weight) of each respondent's data so that the weighted sample demographics (e.g., age distribution, gender balance) match known population figures obtained from reliable sources like census data. This helps make the survey results more representative of the target population.

While weighting can help mitigate certain biases, it's not a magic bullet. It relies on having accurate population data and assumes that respondents within a demographic group hold similar views to non-respondents in that same group, which may not always be true. Weighting can also increase the variance of estimates, potentially widening the margin of error. It's a complex technique that requires careful application and interpretation.

Telling the Story: Visualizing and Reporting Results

The final step is communicating the findings effectively. This involves summarizing key results, interpreting their meaning in the context of the research questions, and acknowledging the study's limitations. Clear and concise reporting is essential for ensuring the insights derived from the survey are understood and utilized appropriately.

Data visualization plays a crucial role in making complex information accessible. Charts (like bar charts, pie charts, line graphs) and tables can effectively illustrate patterns, trends, and comparisons within the data. Choosing the right type of visualization for the data and the message being conveyed is key. Visualizations should be clearly labeled, uncluttered, and accurately represent the findings.

Written reports should outline the research objectives, describe the methodology (including sampling, questionnaire design, data collection procedures), present the key findings supported by data and visualizations, discuss the implications of the results, and note any limitations (e.g., potential biases, margin of error) that might affect the interpretation. Transparency about methods allows others to assess the credibility of the findings.

Formal Education Pathways in Survey Design

University Degrees and Relevant Fields

While dedicated undergraduate degrees solely in "Survey Design" are rare, expertise is typically developed within broader disciplinary contexts. Relevant fields of study include Statistics, Sociology, Psychology, Political Science, Public Health, Marketing, Communications, and Economics. These programs often include coursework in research methods, statistical analysis, and potentially specialized courses in survey methodology or questionnaire design.

At the graduate level (Master's or PhD), opportunities for specialization increase significantly. Many universities offer graduate programs or concentrations specifically in Survey Methodology, Survey Research, or Quantitative Methods. These programs provide in-depth training in sampling theory, questionnaire design, measurement error, data collection modes, non-response, data analysis, and ethical considerations. Leading programs often reside within departments of Statistics, Sociology, or joint programs like the Joint Program in Survey Methodology (JPSM) affiliated with the University of Maryland.

A strong foundation in quantitative reasoning and statistical methods is generally essential for advanced study and practice in survey design. Coursework often blends theoretical principles with practical application, preparing graduates for careers in academia, government statistical agencies, market research firms, or non-profit organizations.

Certifications and Professional Development

Beyond formal degrees, various professional certifications and workshops can enhance skills in survey design and methodology. Organizations like the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) and the Insights Association offer resources, conferences, and short courses covering specific topics in survey research. While not always mandatory for employment, certifications can signal specialized expertise and commitment to the field.

Universities and private training providers also offer workshops and certificate programs focused on specific aspects like questionnaire design, sampling techniques, or analysis using particular software (e.g., R, SPSS). These shorter programs can be valuable for professionals seeking to update their skills or gain expertise in a new area without committing to a full degree program.

Continuous learning is important in this evolving field. Staying abreast of new technologies, methodological advancements, and ethical guidelines through workshops, webinars, conferences, and professional literature helps practitioners maintain high standards in their work.

Research Opportunities: Theses and Dissertations

For students pursuing graduate degrees, particularly at the PhD level, conducting original research involving survey design is a core component of their training. Master's theses and doctoral dissertations often involve designing, implementing, and analyzing data from surveys to address specific research questions within their chosen discipline.

These research projects provide invaluable hands-on experience in applying theoretical principles to real-world challenges. Students grapple with sampling decisions, questionnaire development, navigating ethical reviews, managing data collection, analyzing complex data, and interpreting findings. This process develops critical thinking, problem-solving skills, and deep methodological expertise.

Working closely with faculty advisors who are experienced survey researchers provides mentorship and guidance. Presenting research at conferences and publishing findings in peer-reviewed journals further hones communication skills and contributes to the broader body of knowledge in survey methodology or the student's substantive field.

Interdisciplinary Connections

Survey design is inherently interdisciplinary, drawing on insights and techniques from various fields. Statistics provides the mathematical foundation for sampling and analysis. Psychology informs our understanding of how respondents process questions and formulate answers (cognitive psychology) and how social factors influence responses (social psychology).

Sociology and Political Science contribute theories about social structures and attitudes that surveys aim to measure. Computer Science and Data Science are increasingly relevant for developing online survey platforms, managing large datasets, and applying advanced analytical techniques. User Experience (UX) design principles are valuable for creating engaging and user-friendly online questionnaires.

This interdisciplinary nature means that professionals in survey design often collaborate with experts from diverse backgrounds. It also highlights the transferability of survey design skills across different sectors and research areas. A strong grounding in survey methodology can open doors in academic research, government, market research, user research, program evaluation, and more.

Online and Self-Directed Learning in Survey Design

Building Foundational Skills Online

The proliferation of online learning platforms has made acquiring foundational knowledge in survey design more accessible than ever. Numerous online courses cover topics ranging from introductory research methods to specific aspects like questionnaire construction, sampling, and data analysis using statistical software. Platforms like Coursera, edX, and others host courses offered by universities and industry experts.

Online courses offer flexibility, allowing learners to study at their own pace and on their own schedule. This is particularly beneficial for individuals looking to transition careers or working professionals seeking to upskill. Many courses provide a structured curriculum, video lectures, readings, quizzes, and assignments, simulating aspects of a traditional classroom experience. OpenCourser makes it easy to find and compare courses related to social sciences and research methods from various providers.

While online courses provide excellent theoretical grounding and instruction, practical application is key. Look for courses that incorporate hands-on exercises or projects, allowing you to practice designing questions, developing sampling plans, or analyzing mock data sets. Supplementing coursework with independent practice reinforces learning.

These courses offer structured learning paths covering quantitative methods, data collection frameworks, and analysis, suitable for building a solid foundation.

Applying Skills Through Projects

Theoretical knowledge gained from courses becomes truly ingrained through practical application. Undertaking personal projects is an excellent way to solidify understanding and build a portfolio demonstrating your skills. Start with a simple project: identify a research question of personal interest that can be addressed with a small survey.

Go through the entire design process: define objectives, draft a short questionnaire, consider your target audience (even if it's just friends or family initially), think about how you'll distribute it (e.g., using a free online tool), collect a small amount of data, and perform basic analysis. This hands-on experience, even on a small scale, highlights practical challenges and reinforces concepts learned in courses.

As your skills grow, tackle more complex projects. Volunteer to help a local non-profit design an evaluation survey, or collaborate with peers on a research project. Document your process and results. This practical experience is invaluable for learning and highly regarded by potential employers.

Learning Together: Forums and Peer Review

Self-directed learning doesn't have to be solitary. Engaging with online communities, forums (like those associated with specific courses or professional organizations), or study groups provides opportunities to ask questions, share challenges, and learn from others' experiences. Discussing concepts and reviewing each other's work can deepen understanding and expose you to different perspectives.

Participating in forums dedicated to statistical software like R or Python, or platforms used for survey deployment, can provide practical troubleshooting tips and expose you to advanced techniques. Peer review, even informally among fellow learners, can provide constructive feedback on questionnaire design or analysis plans.

Contributing to discussions and helping others also reinforces your own knowledge. The act of explaining a concept or methodology to someone else is a powerful way to solidify your own understanding.

Supplementing Formal Education

Online resources are not just for those learning independently; they are also valuable supplements for students enrolled in formal degree programs. Online courses can offer deeper dives into specific topics not covered extensively in a university curriculum, such as advanced sampling techniques, specific software training, or niche applications like mobile survey design.

Students can use online courses to reinforce difficult concepts encountered in their university classes or to explore related areas like data visualization or programming for data analysis. Platforms like OpenCourser allow students to save courses to a list, helping them plan supplementary learning alongside their formal studies. Accessing diverse perspectives from instructors at different institutions can also enrich understanding.

Furthermore, online tutorials, blogs by survey methodologists, and webinars offered by research organizations provide ongoing learning opportunities to stay current with the latest trends and best practices, complementing the foundational knowledge gained through formal education.

Career Progression and Opportunities

Starting Out: Entry-Level Roles

Individuals with foundational knowledge in survey design and related analytical skills can find opportunities in various entry-level positions. Common roles include Research Assistant, Survey Technician, Data Coordinator, Junior Analyst, or Field Interviewer Supervisor. These positions often involve supporting senior researchers or project managers in various stages of the survey process.

Typical responsibilities might include assisting with questionnaire formatting and testing, programming surveys into online platforms, managing participant recruitment and communication, cleaning and organizing collected data, conducting basic data analysis (e.g., generating frequency tables, descriptive statistics), and helping prepare reports or presentations. These roles provide practical experience and exposure to the day-to-day realities of survey research.

A bachelor's degree in a relevant field (social sciences, statistics, marketing, etc.) combined with strong attention to detail, organizational skills, basic computer proficiency (especially spreadsheets), and good communication abilities are often required. Demonstrating familiarity with survey principles and perhaps some experience with data collection or analysis software through coursework or projects can be advantageous.

Growing Expertise: Mid-Career Specialization

With experience, professionals can specialize in particular aspects of survey design or methodology. Potential mid-career roles include Survey Methodologist, Market Research Manager, Program Evaluator, User Researcher, Data Scientist (with a survey focus), or Senior Research Associate. These positions typically involve greater responsibility for designing studies, managing projects, analyzing complex data, and interpreting results.

Specializations might focus on sampling design, questionnaire development and testing, specific data collection modes (e.g., web surveys, mixed-mode), statistical analysis and modeling, qualitative research methods, or specific subject areas (e.g., health surveys, political polling, customer experience research). A Master's degree or PhD in Survey Methodology or a related quantitative field often facilitates advancement to these more specialized and senior roles.

Strong analytical, problem-solving, project management, and communication skills are essential at this level. Professionals are expected to not only execute research but also to provide methodological guidance, interpret complex findings, and communicate insights effectively to diverse audiences, including clients or policymakers.

Where the Jobs Are: High-Demand Industries

Expertise in survey design is valued across multiple sectors. Government agencies at the federal, state, and local levels employ survey methodologists and statisticians for conducting large-scale surveys (e.g., census, labor statistics, health surveillance). Research institutions and universities hire researchers and survey specialists for academic studies across various disciplines.

The private sector offers numerous opportunities, particularly in market research firms that design and conduct surveys for business clients. Technology companies increasingly employ user researchers who use surveys (among other methods) to understand user experiences and inform product design. Healthcare organizations, non-profits, and political polling organizations also rely heavily on survey expertise for data collection and analysis. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, employment for market research analysts, a common career path utilizing survey skills, is projected to grow much faster than the average for all occupations.

The specific skills in demand may vary by industry; for example, market research may emphasize consumer behavior and branding, while public health focuses on epidemiology and health outcomes. However, the core principles of sound survey design and analysis remain fundamental across sectors.

Going Independent: Freelance and Consulting

Experienced survey professionals may choose to work independently as freelancers or consultants. This path offers flexibility and the opportunity to work on diverse projects across different industries. Consultants might advise organizations on survey design, oversee data collection efforts, conduct complex analyses, or provide training on survey methods.

Success in consulting requires not only strong methodological expertise but also excellent business development, client management, and communication skills. Building a network of contacts and establishing a reputation for high-quality work are crucial. Freelancers often specialize in specific niches, such as survey programming on particular platforms, qualitative data analysis, or statistical consulting.

While offering autonomy, freelance work also involves managing administrative tasks, marketing services, and dealing with fluctuating workloads. It often appeals to seasoned professionals with established track records and strong self-discipline.

This course touches upon consulting tools and approaches, which can be relevant for those considering freelance work.

This book offers a practical perspective on research which is valuable for applied roles.

Emerging Trends in Survey Design

Smarter Surveys: AI and Adaptive Questionnaires

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning are beginning to influence survey design. One emerging trend is the development of adaptive questionnaires. These surveys dynamically adjust the questions presented to each respondent based on their previous answers, tailoring the experience and potentially reducing survey length while maximizing relevant information gathered. AI might also be used to analyze open-ended text responses more efficiently or even generate draft survey questions based on research objectives.

Chatbots are being explored as a way to administer surveys in a more conversational and engaging format, potentially improving respondent experience, particularly for younger demographics. AI can also assist in identifying complex patterns or anomalies in survey data during the analysis phase.

While promising, the application of AI in surveys is still evolving. Ensuring fairness, transparency, and avoiding algorithmic bias are critical ethical considerations as these technologies become more integrated into the survey process.

Going Small and Mobile: Micro-Surveys and Mobile-First Design

With the ubiquity of smartphones, survey design is increasingly adopting a "mobile-first" approach. This means designing questionnaires specifically for smaller screens, considering touch-based interactions, and optimizing for potentially shorter attention spans in a mobile context. Questions need to be concise, layouts simple, and response options easy to select on a touchscreen.

Relatedly, there is growing interest in micro-surveys – very short surveys, sometimes just a single question, often delivered in context (e.g., immediately after a customer service interaction or website visit). These aim to capture immediate feedback with minimal respondent burden. While useful for specific pulse checks, they typically lack the depth and breadth of traditional surveys.

Designing effectively for mobile requires understanding user behavior in that environment and testing questionnaires rigorously across different devices and operating systems to ensure a seamless experience.

Connecting the Dots: Integration with Big Data

Surveys are increasingly being used in conjunction with other data sources, often referred to as "Big Data" – large, complex datasets generated from digital transactions, social media, sensors, or administrative records. Instead of relying solely on self-reported information, researchers might link survey responses to behavioral data (e.g., purchase history, website clicks) or administrative records to gain a more holistic understanding.

This integration offers powerful possibilities, potentially enriching survey insights with objective behavioral measures or validating self-reported data. However, it also raises significant challenges related to data linkage, privacy protection, and the potential biases inherent in different data sources. Methodological research is ongoing to develop best practices for combining survey data with other data streams responsibly and effectively.

This book discusses connections between health and environmental data, hinting at the integration of diverse data sources.

The Challenge of Engagement: Declining Response Rates

A significant challenge facing the survey industry is the general trend of declining response rates across various modes, particularly telephone surveys. People are increasingly busy, wary of unsolicited contacts, and overwhelmed by requests for information. This makes it harder and more expensive to achieve representative samples and raises concerns about potential non-response bias.

Researchers are actively exploring strategies to mitigate this trend. These include improving survey design to be more engaging and respondent-friendly, offering appropriate incentives, utilizing mixed-mode approaches to reach different segments of the population, enhancing communication about the survey's value, and developing advanced statistical techniques to adjust for non-response bias. Organizations like Pew Research Center actively study and report on these challenges.

Addressing declining response rates requires continuous innovation in survey methodology and a renewed focus on building trust and demonstrating the value of participation to potential respondents. It underscores the importance of rigorous design and thoughtful implementation in obtaining reliable data.

Frequently Asked Questions (Career Focus)

What entry-level jobs use survey design skills?

Entry-level roles often involve supporting survey research activities. Titles might include Research Assistant, Data Collection Coordinator, Survey Technician, Junior Market Research Analyst, or Interviewer. Responsibilities typically involve tasks like formatting questionnaires, testing survey instruments, monitoring data collection, cleaning data, performing basic analyses, and assisting with report preparation. These roles provide practical grounding in the survey lifecycle.

How transferable are survey design skills to other fields?

Survey design skills are highly transferable. The ability to define problems, formulate clear questions, understand sampling, manage data, perform quantitative and qualitative analysis, and communicate findings clearly is valuable in many fields. These skills are applicable in market research, user experience (UX) research, program evaluation, data analysis, policy analysis, consulting, and various roles within business intelligence and analytics. The core competencies of rigorous thinking and evidence-based inquiry are widely sought after.

Is certification necessary for industry roles?

While formal certifications in survey methodology exist, they are generally not a strict requirement for most industry roles, especially at the entry level. Practical experience, relevant coursework, strong analytical skills, and familiarity with specific tools (like statistical software or survey platforms) are often more important. However, certifications can sometimes enhance a resume, demonstrate specialized knowledge, and may be more valued for certain advanced or specialized positions, particularly in government or highly technical consulting.

Which industries offer the highest salaries?

Salaries can vary significantly based on experience, education level, specific role, geographic location, and industry. Generally, private sector roles, particularly in technology (user research) and consulting (market research, management consulting), tend to offer higher compensation compared to academia or non-profit sectors. Positions requiring advanced degrees (Master's or PhD) and specialized quantitative skills typically command higher salaries. Government roles often offer competitive salaries and benefits, particularly at federal agencies.

Are there remote work opportunities in this field?

Yes, remote work opportunities are increasingly common in fields utilizing survey design skills, particularly following broader shifts towards remote work. Roles involving survey programming, data analysis, report writing, and project management can often be performed remotely. Data collection modes like online surveys are inherently remote-friendly. While some roles, especially those involving face-to-face interviewing or direct site management, may require physical presence, many analytical and design-focused positions offer partial or full remote flexibility.

How can I transition from academic to applied survey design?

Transitioning from an academic research setting to an applied role (e.g., in industry or government) involves highlighting the practical relevance of your skills. Emphasize experience with project management, data analysis software commonly used in industry (like R, Python, SPSS, or specific survey platforms), data visualization, and communicating complex findings to non-technical audiences. Tailor your resume to focus on tangible outcomes and skills relevant to the specific industry or role. Networking with professionals in your target field, seeking internships or short-term projects, and potentially pursuing additional training focused on applied methods or industry-specific tools can facilitate the transition. Be prepared to adapt to different timelines, reporting styles, and research goals common in applied settings.

Survey design is a dynamic field that combines analytical rigor with careful communication to gather essential insights about human attitudes and behaviors. Mastering its principles requires attention to detail, critical thinking, and a commitment to ethical practice. Whether used for academic inquiry, business strategy, or public policy, well-designed surveys provide a powerful lens for understanding our world. Developing skills in this area opens doors to diverse career paths focused on generating and interpreting data to inform decisions and drive progress. Exploring resources like the OpenCourser Learner's Guide can help you structure your learning journey in this rewarding field.