Supply Chain Planning

Comprehensive Guide to Supply Chain Planning

Supply Chain Planning (SCP) is the intricate process of coordinating and optimizing all the activities involved in getting products from raw materials to the end consumer. Think of it as the central nervous system of a business, ensuring that the right products are in the right place at the right time, and at the right cost. It involves forecasting what customers will want, figuring out how to make or procure those items, managing inventory effectively, and ensuring smooth delivery. In a world where product availability and rapid fulfillment are paramount, SCP is the invisible engine driving customer satisfaction and business success.

Working in Supply Chain Planning can be incredibly engaging. Imagine the satisfaction of orchestrating a complex global network, solving puzzles to overcome disruptions, and seeing your strategies directly impact a company's bottom line and a customer's happiness. It's a field that blends analytical rigor with creative problem-solving, where you might be developing sophisticated forecasting models one day and collaborating with international teams to navigate logistical challenges the next. The dynamic nature of global markets means that no two days are exactly alike, offering continuous learning and opportunities for innovation.

Core Concepts and Processes

Understanding Supply Chain Planning begins with grasping its fundamental components. These processes work in concert to ensure the smooth and efficient flow of goods and services. While each element has its unique focus, they are all interconnected and essential for a well-functioning supply chain.

Demand Planning and Forecasting

Demand planning is the process of predicting future customer demand for a company's products and services. It's a critical first step in SCP because all subsequent planning activities, from sourcing raw materials to scheduling production and managing inventory, depend on an accurate understanding of what customers are likely to buy. Effective demand planning helps businesses avoid stockouts (not having enough product) or overstocking (having too much product, which ties up capital and warehouse space).

Forecasting techniques are the tools used within demand planning to make these predictions. These can range from simple methods, like looking at historical sales data, to more complex statistical models that incorporate factors like seasonality, promotions, economic indicators, and even social media trends. The goal is to create the most accurate possible picture of future demand, enabling the rest of the supply chain to prepare accordingly.

For those looking to build a strong foundation in this area, understanding how to analyze demand data and select appropriate forecasting methods is key. These skills are central to effective Sales and Operations Planning.

These courses can help build a foundation in demand planning and forecasting techniques:

Supply Planning

Once a demand forecast is in place, supply planning kicks in. This process focuses on how the company will meet that anticipated demand. It involves determining the production levels, sourcing strategies, and resource allocation needed to ensure products are available when and where customers want them. Supply planning aims to balance the forecasted demand with the company's capacity and available resources in the most efficient way possible.

Key components of supply planning include capacity planning and material planning. Capacity planning assesses the company's ability to produce goods or deliver services, considering factors like machinery uptime, labor availability, and facility space. If forecasted demand exceeds current capacity, planners must decide whether to increase capacity (e.g., by adding shifts or investing in new equipment) or adjust the demand plan. Material planning, often referred to as Material Requirements Planning (MRP), involves determining the exact quantity and timing of raw materials, components, and subassemblies needed to meet production targets. This ensures that all necessary inputs are available to avoid production delays.

Effective supply planning is crucial for minimizing costs, optimizing resource utilization, and ensuring timely order fulfillment. It requires close coordination with procurement, production, and logistics teams.

Consider these resources for learning more about supply planning:

Inventory Management and Optimization

Inventory management is the art and science of maintaining the right amount of stock to meet demand while minimizing costs. Holding too much inventory ties up capital, increases storage and handling expenses, and risks obsolescence. Conversely, holding too little inventory can lead to stockouts, lost sales, and dissatisfied customers. Inventory optimization strategies aim to find this delicate balance.

This involves deciding how much inventory to hold for each product (safety stock), when to reorder (reorder points), and in what quantities (economic order quantity). Techniques like ABC analysis (categorizing inventory based on value), Just-in-Time (JIT) inventory systems (receiving goods only as they are needed in the production process), and vendor-managed inventory (VMI) are commonly used. The goal is to ensure product availability, improve cash flow, and reduce the risks associated with holding inventory.

Sophisticated inventory optimization often involves analytical models and software to determine optimal stock levels across the entire supply chain network, considering demand variability, lead times, and service level targets.

To delve deeper into managing and optimizing inventory, these courses and books offer valuable insights:

Sales and Operations Planning (S&OP) / Integrated Business Planning (IBP)

Sales and Operations Planning (S&OP), often evolving into Integrated Business Planning (IBP), is a crucial cross-functional process that aligns demand, supply, and financial plans. It typically involves a monthly cycle of meetings where representatives from sales, marketing, operations, finance, and product development collaborate to create a single, consensus-based operational plan that supports the company's overall business strategy. The S&OP process aims to balance supply and demand at the aggregate level, usually looking out over a rolling 18-24 month horizon.

The primary goal of S&OP/IBP is to ensure that all departments are working from the same playbook, making decisions that are aligned with the company's objectives and financial targets. It helps to improve communication, enhance decision-making, and provide better visibility into potential future imbalances between supply and demand. This allows companies to proactively address issues, such as anticipated capacity constraints or material shortages, before they impact customers or financial performance.

A well-executed S&OP/IBP process leads to improved forecast accuracy, better inventory management, higher customer service levels, and ultimately, increased profitability. It acts as a bridge between strategic planning and day-to-day execution.

These courses offer a comprehensive look into S&OP and IBP:

Distribution Requirements Planning (DRP)

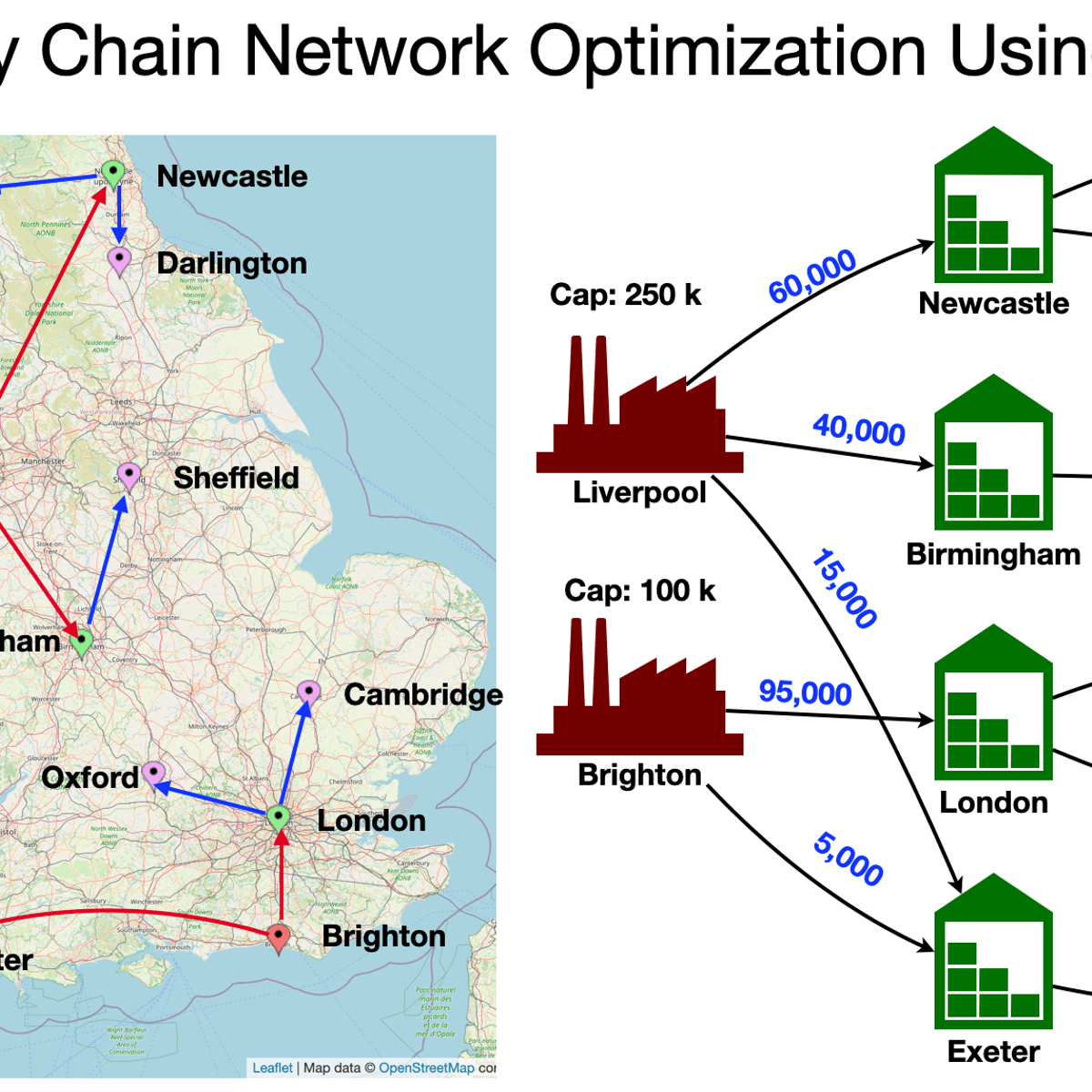

Distribution Requirements Planning (DRP) is a process used to plan and control inventory in a distribution network. It determines the quantity and timing of inventory needed at various points in the distribution system, such as regional warehouses or distribution centers, to meet anticipated demand from downstream locations (e.g., retail stores or customers). DRP is essentially an extension of Material Requirements Planning (MRP) logic into the distribution network.

DRP starts with the forecast of demand at the end-customer level and works backward through the distribution network, calculating the replenishment needs for each stocking location. It considers factors like lead times for transportation, safety stock levels at each location, and order quantities. The output of DRP is a time-phased plan for shipments between distribution centers and from central supply points.

By providing a clear view of future inventory needs across the distribution network, DRP helps to improve product availability, reduce transportation costs through better load consolidation, and optimize inventory levels throughout the system. It ensures that the right products are in the right place to meet customer orders efficiently.

This course provides insights into the logistics aspect of supply chains, which encompasses DRP:

Strategic versus Tactical Planning Horizons

Supply Chain Planning isn't a one-size-fits-all activity. It operates on different timescales, each with distinct objectives, levels of detail, and decision-making focus. Understanding these planning horizons – strategic, tactical, and operational – is crucial for appreciating how different planning activities integrate to achieve overall business goals. These horizons are not isolated; they form a hierarchy, with decisions at higher levels constraining and guiding plans at lower levels.

Long-Term Strategic Planning

Long-term strategic planning in the supply chain typically looks out several years, often three to five years or even longer. The focus here is on making high-level decisions that will shape the fundamental structure and capabilities of the supply chain. These decisions are usually capital-intensive and have a lasting impact on the business.

Examples of strategic planning decisions include designing the overall supply chain network (e.g., where to locate manufacturing plants, distribution centers, and sourcing hubs), making significant capacity expansion or contraction decisions (e.g., building a new factory or closing an existing one), and determining long-term supplier relationships and partnerships. Other strategic considerations might involve investing in major new technologies or deciding which markets to serve and how. The frequency of these planning activities is relatively low, perhaps annually or as major business shifts occur, and the level of detail is aggregate, focusing on product families or business units rather than individual SKUs.

Alignment with the overall corporate strategy is paramount in strategic supply chain planning. The goal is to create a supply chain that can effectively support the company's long-term competitive advantages and growth objectives.

These resources explore the strategic aspects of supply chain design and management:

Mid-Term Tactical Planning

Mid-term tactical planning bridges the gap between long-term strategy and short-term operations. This horizon typically covers a period from a few months up to two years. The primary goal of tactical planning is to effectively allocate and utilize the resources established through strategic decisions to meet anticipated demand in the most efficient manner.

The Sales and Operations Planning (S&OP) or Integrated Business Planning (IBP) process is a cornerstone of tactical planning. It involves creating aggregate plans for sales, production, inventory, and new product introductions. Other tactical decisions include resource allocation across different product lines or customer segments, workforce planning, and managing supplier contracts and performance. Tactical planning usually occurs on a monthly or quarterly cycle and involves a moderate level of detail, often at the product family or category level.

The focus is on balancing supply and demand, optimizing inventory levels, and managing costs within the constraints set by the strategic plan. Effective tactical planning ensures that the company is well-positioned to execute its operational plans smoothly.

These courses offer insights into tactical planning processes:

Short-Term Operational Planning

Short-term operational planning focuses on the day-to-day and week-to-week execution of the tactical plan. This horizon can range from a single day up to a few months. The objective is to make detailed decisions that ensure customer orders are fulfilled on time and in full, while adhering to production schedules and managing immediate resource constraints.

Activities in operational planning include detailed production scheduling, order promising (confirming delivery dates to customers), dispatching of goods, managing daily transportation, and addressing any immediate disruptions or exceptions. This level of planning is highly detailed, often dealing with individual stock-keeping units (SKUs), specific customer orders, and individual machines or work centers. The planning frequency is very high – daily or even intra-day in some dynamic environments.

Operational planning is where the rubber meets the road. It's about executing the plans efficiently and reacting quickly to any unforeseen events, like a machine breakdown or a sudden surge in orders. Success at this level depends heavily on accurate real-time information and effective communication across different operational teams.

These resources cover aspects relevant to operational planning and execution:

Interaction and Alignment of Planning Horizons

It's crucial to understand that these three planning horizons are not independent silos; they are deeply interconnected and must be aligned. Strategic decisions provide the framework and constraints for tactical planning. For example, the number and location of distribution centers (a strategic decision) will dictate the options available for tactical inventory positioning. Similarly, the tactical S&OP plan, which sets aggregate production targets, provides the input for short-term operational scheduling.

Feedback loops are also essential. Information from operational execution (e.g., actual production rates or persistent transportation delays) can inform tactical planners about potential issues with resource availability or capacity assumptions. Likewise, consistent difficulties in meeting tactical plans might signal to strategic planners that the underlying supply chain design or capacity is no longer adequate for current market demands. This hierarchical and iterative nature of planning, with continuous feedback and adjustment, is key to maintaining an agile and responsive supply chain.

A lack of alignment between these horizons can lead to significant problems, such as strategic goals not being met due to unfeasible tactical plans, or operational chaos resulting from poorly conceived tactical directives. Therefore, integrated planning processes and systems that facilitate communication and data flow across all horizons are vital for success.

Key Technologies and Software

Modern Supply Chain Planning is heavily reliant on a diverse array of technologies and software solutions. These tools are essential for managing the complexity, scale, and speed of contemporary global supply chains. They enable planners to analyze vast amounts of data, generate more accurate forecasts, optimize plans, and collaborate more effectively across the organization and with external partners. Without these technological enablers, achieving the levels of efficiency, responsiveness, and resilience demanded by today's markets would be virtually impossible.

The landscape of SCP technology is constantly evolving, with new innovations continually emerging. However, several core categories of systems form the backbone of most companies' planning capabilities. Understanding these different types of software and their roles is important for anyone involved in or aspiring to a career in supply chain planning.

Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) Systems

Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems are foundational software platforms that integrate various business processes and functions across an entire organization into a single system. While ERP systems cover a wide range of areas like finance, human resources, and customer relationship management, they also typically include core modules relevant to Supply Chain Planning. These modules often handle fundamental transactional data related to orders, inventory, production, and procurement.

Within the context of SCP, ERP systems provide the basic data infrastructure. They might include functionalities for basic forecasting, material requirements planning (MRP), and inventory control. For many smaller companies, the ERP system might be their primary planning tool. However, larger or more complex organizations often find that the standard planning capabilities of their ERP systems are not sophisticated enough to meet their advanced planning needs. In such cases, ERPs serve as the critical source of master data and transactional data that feeds into more specialized planning applications.

Effective integration between ERP systems and other planning tools is vital to ensure data consistency and accuracy throughout the planning process.

Understanding how ERP systems function in the context of supply chains is beneficial. These courses provide insights into specific ERP applications in SCP:

Advanced Planning and Scheduling (APS) Systems

Advanced Planning and Scheduling (APS) systems are specialized software solutions designed to provide more sophisticated planning and optimization capabilities than typically found in standard ERP modules. APS systems use advanced algorithms and mathematical models to tackle complex planning challenges across the supply chain, from demand forecasting and inventory optimization to production scheduling and distribution planning.

These systems can handle constraints (like limited production capacity or material availability) more effectively and can generate optimized plans that consider trade-offs between various objectives, such as minimizing costs, maximizing service levels, or reducing lead times. APS solutions often feature modules for strategic network design, demand planning, supply network planning, production planning and detailed scheduling, and transportation planning. They enable "what-if" scenario analysis, allowing planners to evaluate the impact of different decisions or potential disruptions.

APS systems are particularly valuable for companies with complex supply chains, high demand volatility, or significant production constraints. They help to improve planning accuracy, increase operational efficiency, and enhance responsiveness to market changes.

This course offers a look into advanced supply chain systems and network design, which often leverage APS capabilities:

Specific Tools for Demand Forecasting, Inventory Optimization, and S&OP

Beyond comprehensive ERP and APS suites, many organizations utilize specialized, best-of-breed software tools that focus on specific aspects of Supply Chain Planning. For instance, dedicated demand forecasting software might offer more advanced statistical modeling techniques, machine learning capabilities for pattern recognition, and better tools for incorporating causal factors (like promotions or economic indicators) than a generic APS module.

Similarly, specialized inventory optimization tools use sophisticated algorithms to set optimal inventory targets (e.g., safety stock levels) across multiple echelons of the supply chain, considering demand variability, lead time uncertainty, and desired service levels. These tools can help companies significantly reduce inventory holding costs while maintaining or improving product availability.

For Sales and Operations Planning (S&OP) or Integrated Business Planning (IBP), dedicated software platforms facilitate the collaborative planning process. These tools often provide dashboards, scenario modeling capabilities, and workflow management to support the monthly S&OP cycle, helping to align demand, supply, and financial plans across different business functions.

The decision to use specialized tools often depends on the complexity of a particular planning area and the potential benefits that a more focused solution can offer.

These courses cover some of these specialized areas and the analytical tools used:

Emerging Technologies: AI/ML, IoT, and Blockchain

The field of Supply Chain Planning is being significantly impacted by emerging technologies like Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), the Internet of Things (IoT), and blockchain. These technologies are poised to revolutionize how supply chains are planned and managed. AI and ML are being used to develop more accurate demand forecasts by analyzing vast datasets and identifying complex patterns that traditional methods might miss. They can also automate decision-making in areas like inventory replenishment and production scheduling, and even enable self-regulating supply chains.

The Internet of Things (IoT), with its network of connected sensors and devices, provides real-time visibility into the location and condition of goods as they move through the supply chain. This data can be used to improve tracking, monitor quality (e.g., temperature-sensitive products), and trigger alerts in case of deviations or disruptions. This enhanced visibility is crucial for agile and responsive planning.

Blockchain technology offers the potential to create more secure, transparent, and traceable supply chains. By providing a distributed and immutable ledger, blockchain can improve trust among supply chain partners, streamline processes like trade finance and customs clearance, and help combat issues like counterfeiting. While still in earlier stages of adoption for many SCP applications, the transformative potential of these technologies is widely recognized. A recent study highlighted that nearly half (46%) of organizations are already using AI in their supply chains, with logistics and transportation being primary beneficiaries. Furthermore, 68% of supply chain organizations have adopted AI-enabled traceability and visibility solutions, leading to a 22% increase in efficiency.

These courses explore some of these cutting-edge technologies:

Data Integration and Visibility Platforms

Regardless of the specific planning applications used, the ability to integrate data from various sources and achieve end-to-end supply chain visibility is paramount. Data integration platforms and visibility solutions play a crucial role in connecting disparate systems (both internal and external) and creating a single source of truth for planning data. This ensures that all stakeholders are working with consistent and up-to-date information.

Supply chain visibility platforms provide real-time insights into key metrics and events across the supply chain. They often use dashboards and analytics to help planners monitor performance, identify potential disruptions early, and make more informed decisions. Enhanced visibility allows for quicker response to unexpected events and better collaboration with suppliers, logistics providers, and customers.

The trend is towards creating "digital supply chain twins" – virtual replicas of the physical supply chain that allow for simulation, monitoring, and optimization in a dynamic way. Achieving this level of visibility and integration is a key goal for many organizations looking to build resilient and agile supply chains. Effective data management is critical, as highlighted by the fact that 78% of executives report having separate systems for various supply chain functions, creating data silos that hinder strategic decision-making.

This course focuses on the systems and technology aspect of supply chains:

The Role of Data Analytics in Supply Chain Planning

Data analytics has become an indispensable component of modern Supply Chain Planning. The ability to collect, process, analyze, and interpret vast amounts of data is no longer a luxury but a necessity for organizations striving for efficiency, responsiveness, and a competitive edge. In an increasingly complex and volatile global environment, data-driven decision-making empowers supply chain professionals to move beyond intuition and historical precedent towards more precise and proactive planning. From optimizing inventory levels to improving forecast accuracy and managing risks, analytics provides the insights needed to navigate the intricacies of today's supply chains.

The journey towards leveraging data analytics in SCP involves several key aspects, including ensuring data quality, defining relevant performance metrics, applying different types of analytical techniques, and fostering the necessary skills within planning teams. As companies generate and capture more data than ever before, the challenge lies in transforming this raw data into actionable intelligence that drives tangible improvements in supply chain performance.

Criticality of Data Quality and Availability

The adage "garbage in, garbage out" is particularly true for data analytics in Supply Chain Planning. The effectiveness of any analytical model or planning system is fundamentally dependent on the quality and availability of the underlying data. Poor data quality—inaccuracies, inconsistencies, incompleteness, or outdated information—can lead to flawed analyses, incorrect forecasts, suboptimal plans, and ultimately, poor business decisions. Ensuring data integrity is therefore a critical first step.

This involves establishing robust data governance practices, implementing data validation and cleansing processes, and ensuring that data is captured accurately at its source. Data availability is equally important. Planners need timely access to relevant data from various internal systems (like ERP, WMS, TMS) and external sources (like supplier portals, market intelligence providers, IoT devices). Breaking down data silos and creating integrated data platforms are essential for providing a comprehensive and unified view of the supply chain. According to a recent report, 78% of executives acknowledge that their organizations maintain separate systems for inventory, ordering, logistics, and planning, which creates data silos that can undermine strategic decision-making.

Organizations that prioritize data quality and invest in making data readily accessible to planners are better positioned to unlock the full potential of analytics.

These courses can help you understand how to leverage data in supply chain contexts:

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are quantifiable measures used to track and evaluate the performance of Supply Chain Planning processes and outcomes. Well-defined KPIs are essential for understanding how well the supply chain is operating, identifying areas for improvement, and aligning planning activities with overall business objectives. They provide a basis for data-driven decision-making and continuous improvement.

Common KPIs in SCP include forecast accuracy (measuring how close forecasts are to actual demand), inventory turns (measuring how quickly inventory is sold or used), on-time delivery (measuring the percentage of orders delivered by the promised date), order fill rate (measuring the percentage of customer demand met from available stock), and supply chain cycle time (measuring the total time it takes to fulfill a customer order). Other important metrics can relate to cost (e.g., transportation costs, warehousing costs), asset utilization (e.g., capacity utilization), and supplier performance.

The selection of KPIs should be tailored to the specific goals and priorities of the organization. Regularly monitoring these metrics, analyzing trends, and understanding the root causes of performance deviations are crucial for effective SCP.

This book delves into metrics relevant to supply chain performance:

Descriptive, Predictive, and Prescriptive Analytics

Data analytics in Supply Chain Planning can be broadly categorized into three types, each offering a different level of insight and decision support: descriptive, predictive, and prescriptive analytics.

Descriptive analytics focuses on understanding past performance by summarizing historical data. This involves creating reports, dashboards, and visualizations that answer questions like "What happened?" or "What is happening now?". Examples include analyzing past sales trends, current inventory levels, or supplier delivery performance. Descriptive analytics provides a baseline understanding and helps identify areas that may require further investigation.

Predictive analytics uses historical data and statistical techniques, including machine learning, to forecast future outcomes and trends. It answers questions like "What is likely to happen?". Demand forecasting is a prime example of predictive analytics in SCP. Other applications include predicting potential supply disruptions, equipment failures, or changes in transportation costs. Predictive analytics helps planners anticipate future conditions and make proactive decisions.

Prescriptive analytics goes a step further by recommending specific actions or decisions to achieve desired outcomes or optimize performance. It answers questions like "What should we do about it?". This often involves using optimization algorithms and simulation models to evaluate different scenarios and identify the best course of action. Examples include determining optimal inventory levels, selecting the most cost-effective transportation routes, or developing the best production schedule given certain constraints. Prescriptive analytics empowers planners to make data-driven decisions that can significantly improve supply chain efficiency and effectiveness.

The progression from descriptive to predictive and then to prescriptive analytics represents increasing levels of analytical maturity and business value.

These courses provide a deeper dive into analytics applications in supply chains:

Modeling and Simulation

Modeling and simulation are powerful analytical techniques used in Supply Chain Planning for scenario analysis, risk assessment, and decision support. A supply chain model is a mathematical or logical representation of the real-world supply chain, capturing its key entities (e.g., suppliers, plants, warehouses, customers), relationships, and operating rules.

Simulation involves running these models over time, often introducing variability and uncertainty (e.g., demand fluctuations, lead time variations, potential disruptions) to observe how the supply chain behaves under different conditions. This allows planners to conduct "what-if" analyses, testing the impact of various strategies or decisions before implementing them in reality. For example, simulation can be used to assess the resilience of the supply chain to different types of disruptions, evaluate the benefits of adding a new distribution center, or determine the optimal safety stock levels to achieve a target service level.

By providing a virtual environment for experimentation, modeling and simulation help planners to better understand complex supply chain dynamics, identify potential vulnerabilities, and make more robust and informed decisions, particularly in the face of uncertainty. The concept of a "digital supply chain twin" is an advanced form of this, creating a dynamic, real-time virtual replica of the physical supply chain.

This course touches upon optimization, which often involves modeling:

Growing Need for Data Science Skills

The increasing reliance on data analytics and sophisticated planning tools in Supply Chain Planning is driving a growing demand for data science skills within SCP teams. Professionals who can not only understand supply chain processes but also work with data, apply analytical techniques, and interpret the results are becoming highly valuable.

Skills in areas such as data manipulation and analysis (e.g., using Python or R), statistical modeling, machine learning, data visualization, and optimization are increasingly sought after. Furthermore, the ability to communicate complex analytical insights to non-technical stakeholders and translate them into actionable business strategies is crucial. As organizations continue to invest in advanced analytics and AI-driven solutions, the need for supply chain professionals with strong data literacy and analytical capabilities will only intensify. This trend underscores the importance of continuous learning and skill development for those in the SCP field.

For individuals interested in developing these in-demand skills, consider these courses:

Career Pathways and Roles

A career in Supply Chain Planning offers a diverse range of opportunities for individuals with analytical minds, strong problem-solving abilities, and a knack for collaboration. As businesses increasingly recognize the strategic importance of efficient and resilient supply chains, the demand for skilled planning professionals continues to grow. This field provides various entry points and clear progression paths, allowing individuals to build a rewarding and impactful career. Whether you are just starting or looking to advance, understanding the common roles, required skills, and typical career trajectories can help you navigate this dynamic domain.

The cross-functional nature of Supply Chain Planning means that professionals in these roles often interact with many different parts of the organization, from sales and marketing to manufacturing and finance, offering a broad business perspective.

Common Entry-Level Roles

For those beginning their journey in Supply Chain Planning, several common entry-level roles serve as excellent starting points. These positions typically involve supporting more senior planners, learning the core processes and systems, and developing foundational analytical skills.

A Demand Planner is often responsible for generating and maintaining demand forecasts for specific products or product lines. This involves analyzing historical sales data, incorporating market intelligence, and collaborating with sales and marketing teams. A Supply Planner focuses on ensuring that supply can meet the forecasted demand. This might involve monitoring inventory levels, coordinating with production schedulers, and communicating with suppliers about material requirements. A Planning Analyst or Supply Chain Analyst role can be more general, involving data analysis, report generation, and support for various planning activities across the supply chain, such as inventory analysis or logistics coordination. These roles provide a solid grounding in the fundamentals of SCP and exposure to key planning tools and methodologies.

These roles often require a bachelor's degree in supply chain management, business, industrial engineering, or a related field. Strong analytical skills and proficiency with tools like Microsoft Excel are usually essential.

Potential Career Progression Paths

Supply Chain Planning offers significant opportunities for career growth. As professionals gain experience and demonstrate expertise, they can advance to roles with greater responsibility and strategic impact. The progression often involves moving from analyst or planner roles to managerial positions overseeing specific planning functions or broader S&OP processes.

For example, an experienced Demand Planner might become a Demand Planning Manager, leading a team of planners and taking responsibility for the overall demand forecasting process. Similarly, a Supply Planner could progress to a Supply Planning Manager role. A common and highly sought-after progression is into an S&OP Manager or Integrated Business Planning (IBP) Manager position. These roles are critical for facilitating the cross-functional planning process that balances demand, supply, and financial objectives. Further advancement can lead to positions like Planning Manager (overseeing multiple planning functions), Director of Supply Chain Planning, and ultimately to executive roles such as Vice President of Supply Chain or Chief Supply Chain Officer.

The path can also involve specialization in areas like inventory optimization, supply chain analytics, or system implementation. The skills developed in planning roles are highly transferable and can open doors to broader supply chain management or operations leadership positions.

Required Skills and Typical Qualifications

Success in Supply Chain Planning requires a blend of analytical, technical, and soft skills. Analytical skills are paramount, as planners must be able to work with data, identify trends, develop forecasts, and perform quantitative analysis. Problem-solving skills are also crucial, as planners frequently encounter unexpected disruptions or challenges that require creative and timely solutions.

Communication skills are essential for collaborating effectively with various internal departments (sales, marketing, production, finance) and external partners (suppliers, customers, logistics providers). The ability to explain complex plans and analyses clearly is vital. Proficiency with relevant software systems, such as ERP, APS, and specialized planning tools, is increasingly important. Familiarity with data analysis tools and techniques, including Excel pivot tables and potentially data visualization software, is often expected.

Typical qualifications for entry-level roles include a bachelor's degree in supply chain management, operations management, business administration, industrial engineering, or a related quantitative field. For more senior roles, a master's degree (e.g., MBA with a supply chain concentration or an M.S. in Supply Chain Management) can be advantageous, along with relevant professional certifications.

Related Roles

The skills and knowledge gained in Supply Chain Planning are highly transferable to a variety of related roles within the broader supply chain and operations domain. Professionals with a background in planning often find opportunities in areas that work closely with or rely heavily on planning inputs.

For example, a Logistics Analyst or Logistics Manager focuses on the transportation and warehousing aspects of the supply chain, which are directly influenced by distribution and inventory plans. A Procurement Specialist or Procurement Manager deals with sourcing raw materials and services, a process that is tightly linked to material requirements planning and supply planning. An Inventory Manager specializes in optimizing inventory levels and processes, drawing heavily on demand forecasts and supply plans. Furthermore, many supply chain planners transition into Consultant roles, leveraging their expertise to help various companies improve their planning processes and systems.

Understanding these related fields can open up additional career avenues and provide a more holistic view of supply chain management.

Salary Expectations and Job Market Outlook

The job market for Supply Chain Planning professionals is generally positive, driven by the increasing complexity of global supply chains and the critical role of effective planning in business success. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) projects that employment for logisticians, a category that includes many supply chain planning roles, will grow at a rate of 18 percent between 2022 and 2032, which is significantly faster than the average for all occupations.

Salary expectations can vary based on factors such as experience, location, industry, company size, and qualifications. According to Payscale, an entry-level Supply Chain Planner with less than one year of experience can expect an average total compensation of around $59,843 as of early 2025. ZipRecruiter reports an average hourly pay for an Entry Level Supply Chain Planner in the United States at $34.72 as of April 2025, which translates to an annual salary of approximately $72,219. Talent.com suggests an average salary of $72,931 per year for supply chain planners in the USA, with entry-level positions starting around $58,749. Zippia indicates an average salary of $80,668 for supply chain planners, with entry-level salaries around $58,000. These figures can increase significantly with experience and added responsibilities. For instance, mid-career planners often earn more, and senior roles or specialized positions can command higher salaries.

It's advisable to research salary benchmarks for specific roles and locations using resources like BLS Occupational Outlook Handbook, Payscale, Glassdoor, and Zippia to get the most current and relevant information. Generally, roles in high-cost-of-living areas or in industries with complex supply chains (like pharmaceuticals or high-tech manufacturing) may offer higher compensation.

Internships, Co-ops, and Graduate Programs

For students and recent graduates looking to enter the field of Supply Chain Planning, internships and co-operative education (co-op) programs offer invaluable practical experience. These opportunities allow aspiring planners to apply their academic knowledge in a real-world business environment, learn from experienced professionals, and develop key skills. Many companies use internship and co-op programs as a way to identify and recruit future full-time employees.

Gaining hands-on experience with planning software, participating in team meetings, and contributing to actual planning tasks can significantly enhance a resume and provide a competitive edge in the job market. These experiences also help individuals clarify their career interests within the broader supply chain domain.

For those seeking to deepen their expertise or accelerate their career progression, graduate programs specializing in supply chain management can be highly beneficial. Master of Science (M.S.) in Supply Chain Management programs or MBA programs with a concentration in SCM offer advanced coursework, research opportunities, and networking connections that can lead to more senior roles and higher earning potential. These programs often cover advanced planning techniques, strategic supply chain design, analytics, and leadership skills.

Exploring options on OpenCourser's Career Development browse page can also provide resources for skill enhancement and career planning.

Formal Education in Supply Chain Management

A strong educational foundation is often a key stepping stone into the world of Supply Chain Planning and Management. As the field becomes more complex and data-driven, employers increasingly seek candidates with specialized knowledge and analytical capabilities. Formal education, from foundational coursework in high school to advanced degrees and professional certifications, provides the theoretical understanding and practical skills necessary to excel in this dynamic profession. Understanding the educational pathways available can help aspiring supply chain professionals make informed decisions about their learning journey.

Relevant High School Coursework

While specific supply chain courses are rare at the high school level, students interested in this career path can build a strong foundation by focusing on certain subjects. Mathematics courses, including algebra, statistics, and calculus, are particularly valuable as they develop the analytical and quantitative reasoning skills essential for forecasting, optimization, and data analysis in supply chain roles. Economics provides an understanding of market dynamics, supply and demand principles, and global trade, all of which are relevant to supply chain management.

Business courses can offer an introduction to general business concepts, management principles, and an overview of different functional areas within a company. Computer science or information technology classes can also be beneficial, given the increasing reliance on software and data in modern supply chains. Developing strong communication and problem-solving skills through various academic and extracurricular activities will also serve students well in any future supply chain career.

Undergraduate and Graduate Degree Programs

At the university level, many institutions offer specialized degree programs focused on supply chain management and logistics. A Bachelor of Science (B.S.) in Supply Chain Management (SCM) or a Bachelor of Business Administration (B.B.A.) with a major or concentration in SCM are common undergraduate pathways. These programs typically provide a comprehensive understanding of all aspects of supply chain management, including procurement, manufacturing, logistics, inventory management, and, crucially, supply chain planning.

For those seeking more advanced knowledge or looking to accelerate their careers, graduate degrees are a popular option. A Master of Science (M.S.) in Supply Chain Management or Logistics offers in-depth, specialized study. An MBA with a concentration in Supply Chain Management combines SCM expertise with broader business and leadership skills. These graduate programs often delve into advanced analytical techniques, strategic supply chain design, risk management, and global supply chain issues. Many programs also incorporate real-world case studies, industry projects, and opportunities for internships or networking. According to a report by Techneeds, graduates from top supply chain programs can anticipate competitive average salaries.

When choosing a program, consider factors like curriculum, faculty expertise, industry connections, and career placement services. You can explore various Business and Management courses on OpenCourser to supplement your formal education.

These courses provide an overview of supply chain principles often covered in degree programs:

Common Topics in University SCP Courses

University-level courses in Supply Chain Planning and Management cover a wide range of topics designed to equip students with the knowledge and skills needed for the profession. Core subjects often include Operations Management, which explores the design, planning, and control of production and service operations. Demand Forecasting courses delve into various quantitative and qualitative techniques for predicting future demand, as well as methods for measuring forecast accuracy.

Inventory Theory and Management classes focus on models and strategies for optimizing inventory levels, considering costs, service levels, and demand uncertainty. Logistics and Transportation Management covers the movement and storage of goods, including network design, carrier selection, and warehousing operations. A significant component of many programs is Sales and Operations Planning (S&OP) or Integrated Business Planning (IBP), teaching the cross-functional process of balancing demand and supply. Other common topics include procurement and strategic sourcing, supply chain analytics, information systems in SCM, global supply chain management, and sustainability in supply chains.

These courses often blend theoretical concepts with practical applications, using case studies, simulations, and software tools to provide a well-rounded education.

This introductory course touches upon many of these fundamental topics:

PhD Programs and Research Areas

For individuals passionate about advancing the frontiers of knowledge in Supply Chain Planning or pursuing a career in academia or advanced research and development, doctoral programs offer the highest level of specialized study. A Ph.D. in Supply Chain Management, Operations Management, or Industrial Engineering with a focus on SCM allows students to conduct original research and contribute new theories, models, or methodologies to the field.

Research areas within SCP are diverse and constantly evolving. They can include topics such as the application of artificial intelligence and machine learning to demand forecasting and supply chain optimization, developing more resilient supply chain designs, exploring sustainable and ethical supply chain practices, behavioral operations management (understanding human decision-making in supply chains), supply chain finance, and managing risk and disruptions in global networks. PhD programs typically involve rigorous coursework in quantitative methods, operations research, economics, and specialized SCM topics, followed by several years of dissertation research under the guidance of faculty advisors.

Graduates with a Ph.D. in SCM often pursue careers as university professors, researchers in think tanks or government agencies, or as high-level consultants or R&D specialists in industry.

Value of Professional Certifications

In addition to formal academic degrees, professional certifications play a significant role in validating expertise and enhancing career prospects in Supply Chain Planning and Management. These certifications are typically offered by industry associations and demonstrate a practitioner's mastery of a specific body of knowledge and best practices. They are often sought after by employers as an indicator of competence and commitment to the profession.

Two of the most globally recognized certifying bodies in supply chain management are ASCM (Association for Supply Chain Management), formerly APICS, and ISCEA (International Supply Chain Education Alliance). ASCM offers several respected certifications, including the Certified Supply Chain Professional (CSCP) and the Certified in Planning and Inventory Management (CPIM). The CSCP certification provides a broad overview of the entire supply chain, from suppliers to end customers, and is often pursued by professionals looking to understand end-to-end supply chain strategy and management. The CPIM certification focuses more specifically on internal operations, production and inventory management, demand management, and detailed planning and scheduling. Earning these certifications typically involves passing rigorous exams and may require relevant work experience. They can lead to increased earning potential and better job opportunities.

ISCEA also offers valuable certifications such as the Certified Supply Chain Analyst (CSCA). These credentials can be a significant differentiator in the job market and are a valuable complement to academic qualifications.

Consider these courses as preparation for or to understand the scope of such certifications:

Alternative Learning and Skill Development

While formal education provides a strong theoretical and structural foundation, the journey of learning and skill development in Supply Chain Planning doesn't end with a degree or certificate. The field is dynamic, with new technologies, strategies, and challenges emerging continuously. Alternative learning pathways, such as online courses, independent study, and professional networking, offer flexible and accessible ways for students to supplement their education, for practitioners to stay current, and for career changers to gain entry into this exciting domain. These avenues can be particularly valuable for acquiring specific skills or knowledge in a rapidly evolving landscape.

Embracing these non-traditional methods allows individuals to tailor their learning to their specific needs and career goals, fostering a mindset of continuous professional development that is highly valued in the supply chain profession.

Online Courses and MOOCs

Online courses and Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) have revolutionized access to education, and Supply Chain Planning is no exception. Numerous platforms offer a wide array of courses covering everything from fundamental SCP concepts to advanced analytical techniques and specialized software tools. These courses can be invaluable for individuals looking to build foundational knowledge, deepen their understanding of specific areas, or acquire new, in-demand skills.

For students, online courses can supplement their formal university education by providing different perspectives or covering topics not available in their curriculum. For working professionals, they offer a flexible way to upskill or reskill without the commitment of a full-time degree program. Career changers can use online courses to gain the necessary knowledge to pivot into supply chain roles. Many online courses are offered by reputable universities and industry experts, and some even provide certificates of completion or contribute towards professional development units for certifications. OpenCourser is an excellent resource for finding and comparing such online learning opportunities, allowing learners to easily browse through thousands of courses in Logistics and related fields.

These courses are great examples of online learning opportunities for SCP fundamentals:

Independent Study: Online Resources, Books, and Publications

Beyond structured online courses, a wealth of information is available for independent study in Supply Chain Planning. The internet hosts numerous blogs, articles, white papers, and webinars from industry experts, consulting firms, and academic institutions. These resources often cover current trends, best practices, and emerging technologies in SCP. Following thought leaders and reputable organizations on professional networking sites like LinkedIn can also provide a steady stream of valuable insights.

Books remain a cornerstone of in-depth learning. Many classic and contemporary texts cover the theoretical foundations and practical applications of supply chain planning. Industry publications, such as specialized magazines and academic journals, offer cutting-edge research and case studies. Engaging in independent study requires discipline and a proactive approach to seeking out and consuming relevant information, but it can be a highly effective way to build deep expertise and stay ahead of the curve.

OpenCourser's vast library of books can be a great starting point. For instance, these books are considered foundational in the field:

Supplementing Formal Education and Continuous Professional Development

Alternative learning methods are not just for those without formal SCM education; they are also highly beneficial for individuals with degrees and certifications. Online courses and independent study can help supplement formal education by providing practical skills in specific software (like SAP SCM or advanced Excel techniques), exploring niche topics (like sustainable supply chain planning or AI applications), or offering different perspectives on established concepts.

For working professionals, continuous professional development (CPD) is crucial in a field as dynamic as Supply Chain Planning. Technologies evolve, market conditions shift, and new regulations emerge. Regularly engaging with online learning resources, attending webinars, reading industry publications, and participating in workshops helps professionals stay current, learn new skills, and maintain their competitive edge. Many professional certifications also require ongoing education credits, and online courses are often an approved way to meet these requirements. OpenCourser's Learner's Guide offers tips on how to structure self-learning and make the most of online educational resources.

Personal Projects and Practical Application

One of the best ways to solidify learning and demonstrate practical skills is by undertaking personal projects. For aspiring or current supply chain planners, this could involve applying concepts learned from online courses or books to real-world or simulated scenarios. For example, one might try to analyze publicly available retail data to develop a demand forecast for a product category, or use spreadsheet software to build a simple inventory optimization model for a hypothetical small business.

Another project could involve simulating a simple supply chain to understand the impact of disruptions or changes in lead times. Some online courses include hands-on projects or case studies that provide practical experience. Creating a portfolio of such projects can be a powerful way to showcase abilities to potential employers, especially for those transitioning into the field or seeking entry-level positions. These activities bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application, fostering deeper understanding and skill development.

This course provides an example of a project-based learning experience:

Networking via Industry Associations and Online Communities

Learning in Supply Chain Planning is not solely an individual pursuit. Networking with peers, mentors, and industry experts through professional associations and online communities can be an invaluable source of knowledge, insights, and career opportunities. Organizations like ASCM, CSCMP (Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals), and ISCEA host conferences, seminars, and local chapter meetings that facilitate learning and networking.

Online forums, LinkedIn groups, and other digital communities dedicated to supply chain management provide platforms for asking questions, sharing experiences, and discussing current trends and challenges. Engaging in these communities can expose learners to different perspectives, practical solutions to common problems, and emerging best practices. Networking can also lead to mentorship opportunities, collaborations, and awareness of job openings. Building a strong professional network is an ongoing process that complements other forms of learning and skill development, contributing to long-term career success.

Global Dimensions and Ethical Considerations

Supply Chain Planning in the 21st century inherently operates within a globalized and interconnected world. This international scope brings immense opportunities but also significant complexities and responsibilities. Planners must navigate diverse regulatory environments, manage extended lead times, and account for geopolitical risks. Beyond operational efficiency, there's a growing imperative to address the ethical dimensions of supply chains, including sustainable sourcing, fair labor practices, and environmental impact. Building resilient and responsible supply chains is no longer just a matter of good corporate citizenship; it's increasingly a strategic necessity for long-term success and maintaining stakeholder trust.

Complexities of Planning Global Supply Chains

Planning for global supply chains introduces a host of complexities not typically encountered in purely domestic operations. Extended lead times due to international shipping and customs clearance require more sophisticated forecasting and inventory management strategies. Planners must contend with a patchwork of different national regulations, trade agreements, tariffs, and import/export controls, which can change frequently. Currency fluctuations can impact costs and profitability, adding another layer of uncertainty.

Cultural differences, language barriers, and varying business practices across countries can also pose challenges in communication and collaboration with international suppliers and partners. Furthermore, geopolitical instability, natural disasters, and public health crises in one part of the world can have cascading effects across an entire global supply network, highlighting the need for robust risk assessment and contingency planning. Successfully managing these complexities requires a deep understanding of international trade, strong analytical capabilities, and a proactive approach to risk management.

These resources touch upon the global nature of modern supply chains:

Ethical Considerations in SCP

The ethical dimensions of Supply Chain Planning are gaining increasing prominence. Businesses face growing scrutiny from consumers, investors, and regulatory bodies regarding the social and environmental impact of their supply chains. Ethical considerations encompass a wide range of issues, including sustainable sourcing of raw materials, ensuring fair labor practices and safe working conditions within supplier factories, and minimizing the environmental footprint of production and logistics activities.

Supply chain planners have a role to play in promoting ethical practices. This can involve incorporating sustainability criteria into supplier selection and evaluation processes, working with suppliers to improve their environmental and social performance, and designing supply chains that reduce waste and emissions. Transparency and traceability are key to addressing ethical concerns, allowing companies to identify and mitigate risks related to issues like forced labor, deforestation, or pollution within their extended supply networks. A 2024 report on the State of Supply Chain Sustainability by MIT CTL and CSCMP highlights increasing investor pressure for sustainability and the need for better Scope 3 emissions accounting. Many companies are now setting ambitious sustainability goals, and supply chain planning is critical to achieving them.

These courses and resources address sustainability and ethical practices:

Supply Chain Risk and Resilience

Modern supply chains are exposed to a wide array of risks, including natural disasters, geopolitical conflicts, supplier failures, transportation disruptions, cyber-attacks, and demand volatility. Effective Supply Chain Planning must therefore incorporate robust risk management practices aimed at identifying potential threats, assessing their likelihood and impact, and developing strategies to mitigate them. Building supply chain resilience—the ability to prepare for, respond to, and recover quickly from disruptions—is a key objective.

Strategies for enhancing resilience include diversifying the supplier base to reduce dependence on single sources, increasing inventory buffers for critical components, developing alternative transportation routes, improving supply chain visibility to detect disruptions early, and fostering stronger collaboration with key partners. Scenario planning and simulation can help planners understand potential vulnerabilities and test the effectiveness of different mitigation strategies. As global uncertainties persist, the focus on building agile and resilient supply chains will continue to be a top priority for organizations.

These resources delve into risk management and resilience:

International Availability of Roles and Skills Transferability

The principles and practices of Supply Chain Planning are largely universal, making the skills acquired in this field highly transferable across different countries and industries. While specific market conditions, regulations, and cultural nuances will vary, the core concepts of demand forecasting, supply planning, inventory management, and S&OP are globally relevant. This means that professionals with expertise in SCP often have opportunities to work in international settings or for multinational corporations.

Many large companies have global or regional planning hubs, creating demand for planners who can operate in diverse environments and manage cross-border complexities. The ability to speak multiple languages or experience working in different cultural contexts can be a significant asset for those seeking international roles. Furthermore, the increasing adoption of standardized planning software and methodologies across the globe also facilitates skills transferability. As businesses continue to expand their international operations, the demand for supply chain planners with a global mindset is likely to remain strong.

Impact of Trade Policies and Tariffs

Trade policies, tariffs, and international agreements can have a profound impact on Supply Chain Planning. Changes in these areas can affect the cost of goods, lead times, sourcing decisions, and the overall structure of supply chain networks. For example, the imposition of new tariffs can make products from certain countries more expensive, prompting companies to re-evaluate their sourcing strategies or even consider relocating production.

Supply chain planners must stay informed about current and potential changes in trade policies and be prepared to adapt their plans accordingly. This might involve modeling the financial impact of different tariff scenarios, identifying alternative sourcing locations, or adjusting inventory strategies to mitigate potential disruptions or cost increases. The uncertainty surrounding trade policies in recent years has underscored the importance of agility and flexibility in supply chain design and planning. Companies that can quickly adapt to shifts in the global trade landscape are better positioned to maintain their competitiveness.

This course discusses issues that can arise in global supply chains, including trade impacts:

Current Challenges and Future Trends

The landscape of Supply Chain Planning is in a constant state of flux, shaped by evolving market dynamics, technological advancements, and global events. Professionals in this field face a persistent array of challenges that require adaptability, innovation, and strategic foresight. Simultaneously, emerging trends are redefining how supply chains operate, offering new opportunities for efficiency, resilience, and value creation. Staying abreast of these challenges and trends is crucial for practitioners aiming to navigate the complexities of modern supply chains and for organizations seeking to build a competitive edge. The ability to anticipate and respond to these shifts will determine the future success of supply chain operations worldwide.

Major Challenges Facing SCP Professionals

Supply Chain Planning professionals today grapple with a multitude of pressing challenges. Demand volatility remains a significant hurdle, as shifting consumer preferences, economic uncertainties, and unforeseen events make it increasingly difficult to accurately predict future demand. Supply disruptions, stemming from geopolitical tensions, natural disasters, supplier issues, or transportation bottlenecks (like port congestion and the Red Sea crisis), continue to threaten the flow of goods and materials.

Data overload is another common issue; while more data is available than ever before, extracting meaningful insights and ensuring data quality can be overwhelming without the right tools and skills. The global talent shortage also extends to the supply chain field, with many companies struggling to find and retain individuals with the necessary analytical and technological competencies. Rising costs due to inflation and increasing pressure to operate sustainably add further layers of complexity. Navigating these multifaceted challenges requires robust planning processes, advanced analytical capabilities, and a proactive approach to risk management.

Key Trends Shaping the Future of SCP

Several key trends are actively shaping the future trajectory of Supply Chain Planning. Digitalization is at the forefront, with companies increasingly adopting digital technologies to enhance visibility, improve collaboration, and automate processes across the supply chain. The adoption of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) is accelerating, offering transformative potential in areas like demand forecasting, inventory optimization, and even autonomous planning. Reports indicate that around 40% of supply chain organizations are already investing in Generative AI. The global AI in Supply Chain market is projected to grow significantly, reaching around USD 157.6 billion by 2033, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 42.7%.

There's a growing focus on sustainability and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria, with companies striving to create more ethical and environmentally friendly supply chains. Enhanced supply chain visibility and transparency are becoming critical for managing risks and meeting customer expectations. Consequently, there's an increased need for agility and resilience to better withstand disruptions and adapt to rapidly changing market conditions. The move towards integrated ecosystems and collaborative networks is also a significant trend, facilitating real-time data sharing and joint planning.

These courses explore future-looking aspects of SCM:

The Concept of the 'Digital Supply Chain Twin'

A particularly exciting trend is the development and adoption of the 'digital supply chain twin'. This concept involves creating a dynamic, virtual replica of an organization's entire physical supply chain. This digital twin integrates real-time data from various sources – including IoT devices, ERP systems, transportation management systems, and supplier networks – to provide a comprehensive and up-to-date model of supply chain operations.

The benefits of a digital twin are numerous. It allows planners to visualize the entire value chain, monitor performance in real-time, and identify potential bottlenecks or disruptions before they escalate. Perhaps most powerfully, it enables sophisticated "what-if" scenario analysis and simulation. Planners can test the impact of different strategies, such as changing sourcing locations, adjusting inventory policies, or responding to unexpected events, in a risk-free virtual environment. This helps in making more informed, data-driven decisions and in building more resilient and optimized supply chains. As technology matures, digital twins are expected to become increasingly integral to advanced supply chain planning and control.

Impact of Economic Cycles and Geopolitical Instability

Supply Chain Planning strategies are significantly influenced by broader economic cycles and geopolitical instability. Economic downturns can lead to reduced consumer demand, forcing planners to adjust forecasts downwards, optimize inventory to reduce holding costs, and focus on cost-saving measures. Conversely, periods of economic growth may require scaling up capacity and ensuring supply can meet rising demand. Fluctuations in interest rates, inflation, and currency exchange rates also directly impact supply chain costs and investment decisions.

Geopolitical instability, such as trade disputes, political conflicts, or changes in government policies, can create significant uncertainty and risk for global supply chains. These events can disrupt transportation routes, impact supplier reliability, and lead to sudden changes in tariffs or trade regulations. In response, supply chain planners must focus on building resilience, perhaps by diversifying supplier bases (e.g., through reshoring or "friend-shoring" initiatives), increasing visibility into their multi-tier supply networks, and developing contingency plans for various geopolitical scenarios. The ability to adapt quickly to these external shocks is a hallmark of effective SCP.

Evolution of the SCP Skillset for the Future

As Supply Chain Planning becomes more technologically advanced and data-driven, the skillset required for success in this field is evolving. While traditional planning skills remain important, there's a growing need for professionals who are adept at leveraging new technologies and analytical tools. Proficiency in data analytics, including the ability to work with large datasets, apply statistical methods, and use data visualization tools, is becoming essential.

Familiarity with AI/ML concepts and their application in planning will be increasingly valuable. Beyond technical skills, capabilities in cross-functional collaboration, communication, and change management are critical as planning processes become more integrated and as organizations undergo digital transformations. Supply chain professionals will also need to be adaptable and committed to continuous learning to keep pace with the rapid evolution of the field. The future supply chain planner will likely be a more strategic, data-savvy, and technologically empowered professional who can navigate complexity and drive value for the organization.

OpenCourser's Professional Development section offers resources that can help in acquiring these evolving skills.

Frequently Asked Questions (Career Focused)

Embarking on or advancing a career in Supply Chain Planning can bring up many questions. This section aims to address some of the common queries that students, career changers, and even current practitioners might have. Understanding these aspects can help you make more informed decisions about pursuing and navigating a career in this dynamic and rewarding field.

What kind of companies hire Supply Chain Planners?

Supply Chain Planners are in demand across a vast array of industries because virtually any company that produces, distributes, or sells physical products needs to manage its supply chain effectively. Manufacturing companies of all types, from automotive and electronics to consumer packaged goods (CPG) and industrial equipment, heavily rely on planners to manage production schedules, material flow, and inventory. Retailers, both brick-and-mortar and e-commerce, need planners to forecast demand, manage inventory across distribution centers and stores, and ensure product availability for customers.

Logistics and transportation companies, including third-party logistics providers (3PLs), also employ planners to optimize routes, manage warehouse capacity, and coordinate shipments. Furthermore, industries like pharmaceuticals, aerospace, and technology, which often have complex and highly regulated supply chains, have a significant need for skilled planners. Even some service industries that manage physical assets or consumables will have roles related to supply chain planning. The breadth of industries ensures a wide range of opportunities for those with SCP skills.

Is Supply Chain Planning a stressful job?

Like many roles that involve managing complex systems and responding to dynamic situations, Supply Chain Planning can have its stressful moments. Planners are often responsible for balancing competing objectives (e.g., minimizing costs while maximizing customer service) and dealing with unexpected disruptions (e.g., supplier delays, transportation issues, sudden demand spikes). The need to make quick decisions under pressure, often with incomplete information, can contribute to stress.

However, the level of stress can vary significantly depending on the industry, the company culture, the specific role, and the individual's coping mechanisms. Companies with well-defined processes, effective communication channels, and supportive team environments may experience lower stress levels. While the job can be demanding, many planners find it highly rewarding due to the direct impact they have on the business and the intellectual challenge of solving complex problems. Developing strong organizational skills, effective communication, and problem-solving abilities can help manage the potential stressors of the job. According to Payscale, supply chain planners report a job satisfaction rating of 3.63 out of 5, indicating a generally positive level of satisfaction.

What is the typical starting salary for an entry-level planning role?

Typical starting salaries for entry-level Supply Chain Planning roles in the United States can vary based on factors like location, the specific industry, the size and type of company, and the candidate's qualifications and internships. As of early 2025, several sources provide a general range. Payscale suggests an average total compensation of around $59,843 for an entry-level Supply Chain Planner with less than one year of experience. ZipRecruiter reports an average hourly pay equating to an annual salary of approximately $72,219 for Entry Level Supply Chain Planners.

Talent.com indicates that entry-level positions start around $58,749 per year. Zippia notes that entry-level supply chain planner salaries are around $58,000 annually. In the UK, entry-level salaries for Supply Chain Planners typically range from £24,000 to £28,000 per year. It is important to research current salary data for specific locations and roles using up-to-date salary aggregator websites and industry reports to get the most accurate picture. Keep in mind that these are base figures and may not include bonuses or other forms of compensation.

Do I need an advanced degree (Masters/MBA) to succeed in Supply Chain Planning?

While an advanced degree such as a Master's in Supply Chain Management or an MBA with a supply chain concentration can certainly be beneficial and may accelerate career progression, it is not always a strict requirement for success in Supply Chain Planning, especially for entry-level and mid-level roles. Many successful supply chain planners have built their careers with a bachelor's degree in fields like supply chain management, business, engineering, or economics, coupled with relevant work experience and professional certifications.

An advanced degree can provide deeper specialized knowledge, enhanced analytical skills, and a broader strategic perspective, which can be particularly advantageous for those aspiring to senior leadership positions or highly specialized roles. It can also offer valuable networking opportunities. However, practical experience, a strong track record of performance, continuous learning, and relevant professional certifications (like CSCP or CPIM) can also pave the way for significant career advancement. The decision to pursue an advanced degree often depends on individual career goals, the specific industry and company culture, and personal circumstances.

How important is coding or data science knowledge for a career in SCP?

The importance of coding and data science knowledge in Supply Chain Planning is steadily increasing. As SCP becomes more data-driven and reliant on advanced analytics and AI/ML tools, professionals with skills in these areas are becoming more valuable. While deep coding expertise might not be required for all planning roles, a foundational understanding of data analysis techniques and familiarity with relevant software (like advanced Excel, SQL for database queries, or even Python for data manipulation and modeling) can be a significant advantage.

For roles specifically focused on supply chain analytics, demand modeling, or optimization, data science skills are often essential. Even for general planning roles, the ability to interpret data, understand analytical models, and communicate effectively with data scientists or IT teams is becoming more critical. As companies increasingly adopt sophisticated planning systems and AI-driven solutions, a certain level of data literacy and comfort with analytical tools will be expected. Continuous learning in these areas can greatly enhance career prospects. You can explore Data Science courses on OpenCourser to build these skills.

What are the key differences between Supply Chain Planning and Logistics roles?