Supply Chain Management

Navigating the Network: An Introduction to Supply Chain Management

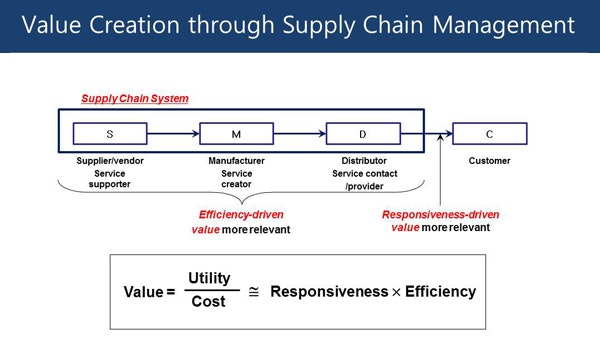

Supply Chain Management (SCM) is the broad range of activities required to plan, control, and execute a product's flow, from acquiring raw materials and production through distribution to the final customer, in the most streamlined and cost-effective way possible. It encompasses the planning and management of all activities involved in sourcing and procurement, conversion, and all logistics management activities. Crucially, it also includes coordination and collaboration with channel partners, which can be suppliers, intermediaries, third-party service providers, and customers. In essence, SCM integrates supply and demand management within and across companies.

Working in Supply Chain Management can be an engaging and exciting field. Professionals in this area often find satisfaction in optimizing complex systems, ensuring that goods and services reach their destinations efficiently, which is vital for the functioning of global commerce. The field is also at the forefront of adopting new technologies, such as artificial intelligence and blockchain, to enhance visibility and resilience, making it a dynamic and forward-looking career. Furthermore, with a growing emphasis on sustainability, SCM professionals play a crucial role in developing and implementing ethical and environmentally responsible practices, contributing to a more sustainable global economy.

What is Supply Chain Management? An ELI5 Explanation

Imagine you want to bake a cake. First, you need ingredients: flour, sugar, eggs, and chocolate. You buy these from a grocery store. The grocery store got them from different places: the flour from a mill, the sugar from a refinery, the eggs from a farm, and the chocolate from a factory. Each of those places also got their "ingredients" from somewhere else. For example, the mill got wheat from a farmer, and the chocolate factory got cocoa beans from a different farmer, perhaps in another country.

Supply Chain Management is like being the master coordinator for making sure all these steps happen smoothly, not just for your one cake, but for thousands or even millions of cakes (or cars, phones, clothes, medicines – anything you can think of!). It's about getting the right things (like ingredients or parts) to the right place (like the factory or the store) at the right time, in the right amount, and in good condition, all while trying to spend as little money as possible and keeping everyone happy – from the first supplier to the final customer who buys the cake.

Think of it as a giant, interconnected network. If one part of the chain breaks – say, the truck carrying eggs to the grocery store gets a flat tire – it can affect everything down the line. A good supply chain manager tries to predict these problems, have backup plans, and keep everything moving efficiently. They use information, technology, and teamwork to make sure you can get your cake ingredients (or any other product) when you want them.

Historical Evolution of Supply Chain Management

Understanding the journey of supply chain management from its rudimentary forms to today's sophisticated, technology-driven operations offers valuable context for anyone considering a career in this field. The evolution reflects broader economic, technological, and social changes that have shaped global commerce.

From Localized Trade to Early Industrial Logistics

In the pre-industrial era, supply chains were predominantly localized. Trade was often restricted by geographical proximity, and logistics were manual and labor-intensive. The movement of goods relied on basic transportation methods like animal-drawn carts and sailing ships. Record-keeping was manual, and coordination between different parties was slow and often unreliable. The focus was primarily on acquiring raw materials and distributing finished goods within a limited region. Efficiency was less about complex optimization and more about the basic availability of goods.

The Industrial Revolution marked a significant turning point. Innovations like the steam engine and later, the internal combustion engine, revolutionized transportation, allowing goods to be moved faster and over greater distances. Manufacturing processes became more centralized with the advent of factories. However, the concept of an integrated "supply chain" was still nascent. Businesses focused more on internal production efficiencies rather than the broader network of suppliers and distributors.

Early logistics primarily dealt with the physical movement and storage of goods. There was little strategic coordination beyond immediate transactional relationships. The primary challenges were overcoming physical distances and ensuring the timely delivery of goods without sophisticated forecasting or inventory management techniques. Communication advancements, such as the telegraph, began to improve coordination, but the overall approach remained fragmented compared to modern standards.

20th-Century Innovations: Assembly Lines and Containerization

The 20th century witnessed transformative innovations that laid the groundwork for modern supply chain management. Henry Ford's introduction of the moving assembly line in the early 1900s revolutionized manufacturing by dramatically increasing production speed and efficiency. This mass production capability created a need for more organized and continuous flows of materials into factories and finished goods out to a growing consumer market. While the focus was still heavily on manufacturing, the implications for upstream and downstream activities were profound.

Perhaps one of the most significant logistical innovations of the 20th century was the development of containerization in the mid-1950s by Malcom McLean. Standardized shipping containers dramatically reduced the time, cost, and complexity of loading and unloading goods from ships, trains, and trucks. This innovation facilitated intermodal transportation and was a key enabler of globalization, making it economically viable to source materials and sell products across vast distances.

During this period, especially after World War II, operations research techniques began to be applied to business problems, including logistics. Mathematical models for inventory control, warehousing, and transportation planning started to emerge, bringing a more scientific approach to managing the flow of goods. The rise of large corporations also led to the development of more formal organizational structures for purchasing, distribution, and logistics, though these often operated in silos.

The Digital Revolution: ERP Systems and Automation

The latter part of the 20th century, particularly from the 1970s onwards, was characterized by the digital revolution, which had a profound impact on how supply chains were managed. The advent of computers and information technology enabled businesses to collect, process, and analyze data in ways that were previously impossible. This led to the development of early Material Requirements Planning (MRP) systems, which helped manufacturers plan their raw material needs more effectively based on production schedules.

MRP systems evolved into Manufacturing Resource Planning (MRP II) systems, incorporating broader aspects of manufacturing planning and control. The real game-changer, however, was the emergence of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems in the 1990s. ERP systems aimed to integrate all aspects of a business, including finance, human resources, manufacturing, and supply chain management, into a single information system. This provided unprecedented visibility and control over business operations, facilitating better coordination across different functions and with external partners.

Automation also began to play a more significant role, not just in manufacturing (e.g., robotics) but also in warehousing (e.g., automated storage and retrieval systems) and data processing. The development of electronic data interchange (EDI) allowed businesses to exchange documents like purchase orders and invoices electronically, speeding up transactions and reducing errors. These technological advancements were crucial in enabling more complex and geographically dispersed supply chains.

For those interested in the foundational principles that underpin modern supply chain technologies, understanding these historical developments is key. The following course provides a good overview of how technology and systems are integrated into supply chain management.

Modern Shifts: Lean, Just-in-Time, and Resilience

The late 20th and early 21st centuries saw the widespread adoption of practices like Lean Manufacturing and Just-in-Time (JIT) inventory management, philosophies largely pioneered by Toyota. Lean principles focus on eliminating waste in all its forms, while JIT aims to reduce inventory levels by having materials arrive exactly when they are needed for production. These approaches demanded much tighter coordination with suppliers and a highly efficient logistics network.

The rise of globalization, fueled by trade liberalization and further advancements in transportation and communication technology, led to increasingly complex and extended supply chains. Companies sourced components from numerous countries to minimize costs, creating intricate global networks. While this often led to cost efficiencies, it also introduced new vulnerabilities.

Events like natural disasters, geopolitical instability, and more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic, have starkly highlighted these vulnerabilities. This has led to a significant modern shift in SCM: a much greater emphasis on supply chain resilience and agility. Companies are now exploring strategies like dual sourcing, nearshoring, regionalization, and investing in advanced analytics and AI to better predict and mitigate disruptions. Sustainability and ethical sourcing have also become paramount, driven by consumer demand, regulatory pressures, and a growing corporate understanding of their broader societal impact. Today, SCM is not just about cost and efficiency; it's about managing risk, fostering innovation, and creating sustainable value across the entire network.

These books delve into the strategic aspects of modern supply chain management, including redesign and risk management, which are critical in today's dynamic environment.

Core Components of Supply Chain Management

Supply Chain Management is a multifaceted discipline composed of several interconnected components. Each plays a vital role in the journey of a product or service from its conception to its delivery to the end consumer. Understanding these core components is crucial for anyone aspiring to build a career in this dynamic field, as they form the building blocks of efficient and effective supply chain operations.

Procurement and Supplier Relationship Management

Procurement, often referred to as purchasing, is the process of acquiring goods, services, or works from an external source. It involves identifying needs, finding and selecting suppliers, negotiating contracts, and ensuring timely delivery. Effective procurement goes beyond just minimizing costs; it focuses on securing the best value, which includes quality, reliability, and innovation from suppliers. This function is critical as the cost of procured materials and services often represents a significant portion of a company's total expenses.

Supplier Relationship Management (SRM) is an integral part of procurement. It involves strategically planning for, and managing, all interactions with third-party organizations that supply goods and/or services to an organization in order to maximize the value of those interactions. SRM aims to build collaborative and long-term relationships with key suppliers. This can lead to benefits such as improved supplier performance, access to supplier innovation, reduced supply risks, and better terms. In an era of increasing supply chain complexity and volatility, strong supplier relationships are a key competitive advantage.

Professionals in procurement and SRM need strong negotiation, analytical, and interpersonal skills. They must understand market dynamics, assess supplier capabilities, and manage contracts effectively. The rise of digital procurement tools and platforms is also transforming this space, requiring a new set of technological competencies. Many organizations are also placing greater emphasis on sustainable and ethical sourcing, making these important considerations in procurement decisions.

These courses offer a deeper dive into the sourcing and procurement aspects of supply chain management, which are fundamental for managing supplier relationships effectively.

For those interested in the broader strategic context of sourcing within the supply chain, the following book is a valuable resource.

Understanding the field of Procurement as a related topic can also be beneficial.

Production Planning and Inventory Control

Production planning involves determining how to best utilize a company's manufacturing resources to meet forecasted demand. This includes scheduling production runs, allocating resources such as labor and machinery, and managing work-in-progress inventory. The goal is to produce the right quantity of goods, at the right quality, and at the right time, while minimizing production costs and lead times. Effective production planning is crucial for meeting customer orders and maintaining operational efficiency.

Inventory control, also known as inventory management, is the process of overseeing the constant flow of units into and out of an existing inventory. It involves deciding what to stock, how much to stock, and when to order or produce more. The primary objectives of inventory control are to ensure that enough stock is available to meet customer demand without interruption, while minimizing the costs associated with holding inventory (such as storage, insurance, and obsolescence). Too much inventory ties up capital and increases holding costs, while too little inventory can lead to stockouts and lost sales.

Techniques such as Material Requirements Planning (MRP), Just-in-Time (JIT), and various forecasting models are commonly used in production planning and inventory control. Professionals in this area require strong analytical skills, attention to detail, and an understanding of manufacturing processes. The increasing use of data analytics and automation is enabling more sophisticated and responsive inventory management strategies, such as demand sensing and predictive inventory optimization.

The following courses provide insights into inventory management and production planning, essential skills for SCM professionals.

This book is a classic reference for manufacturing planning and control systems, highly relevant to this component of SCM.

Warehousing and Transportation Logistics

Warehousing involves the storage of goods before they are sold or distributed further. Modern warehousing is more than just storage; it includes activities like receiving, putaway, order picking, packing, and shipping. Efficient warehouse operations are critical for managing inventory effectively, ensuring timely order fulfillment, and minimizing handling costs. Warehouse design, layout, and the use of material handling equipment and Warehouse Management Systems (WMS) are key aspects of this function.

Transportation logistics focuses on the physical movement of goods from one point to another in the supply chain. This includes selecting transportation modes (e.g., truck, rail, air, sea, pipeline), managing carrier relationships, planning routes, and ensuring timely and cost-effective delivery. Transportation is often a significant cost component in the supply chain, and its efficient management can provide a competitive edge. Factors such as fuel costs, regulations, infrastructure, and geopolitical events can all impact transportation logistics.

Professionals in warehousing and transportation logistics need skills in operations management, spatial planning, and network optimization. They must also be adept at using logistics software and understanding transportation regulations. The rise of e-commerce has placed immense pressure on these functions, demanding faster delivery times and more complex fulfillment models, such as last-mile delivery. Technologies like automation, robotics, GPS tracking, and AI are increasingly being used to optimize warehousing and transportation operations.

These courses cover essential aspects of logistics, including warehousing and transportation, which are vital for moving goods efficiently.

Exploring Logistics as a broader subject can provide additional context.

Demand Forecasting and Customer Service

Demand forecasting is the process of predicting future customer demand for products or services. Accurate forecasts are essential for making informed decisions across the supply chain, from procurement and production planning to inventory control and logistics. Forecasting involves analyzing historical sales data, market trends, economic indicators, and other relevant factors. Various statistical methods and, increasingly, machine learning algorithms are used to generate forecasts.

Customer service in the context of SCM refers to the ability of the supply chain to meet customer expectations in terms of product availability, order fulfillment accuracy, delivery timeliness, and post-sales support. Excellent customer service is a key differentiator in today's competitive market. It requires a responsive and agile supply chain that can adapt to changing customer needs and quickly resolve any issues that may arise. Metrics such as on-time delivery, order fill rate, and customer satisfaction are used to measure customer service performance.

Professionals in demand forecasting and customer service need strong analytical skills, communication abilities, and a customer-centric mindset. They play a crucial role in aligning supply chain operations with market demand and ensuring a positive customer experience. The integration of Customer Relationship Management (CRM) systems with SCM systems helps provide a holistic view of customer interactions and preferences, enabling more personalized service and proactive demand shaping.

Understanding demand and ensuring customer satisfaction are critical. These courses touch upon planning and customer-focused aspects.

A related career path that focuses on predicting demand is the Demand Planner.

Emerging Trends in Supply Chain Management

The field of Supply Chain Management is constantly evolving, driven by technological advancements, shifting global dynamics, and changing societal expectations. Staying abreast of these emerging trends is crucial for professionals and organizations aiming to maintain a competitive edge and build resilient, efficient, and sustainable supply chains for the future. These trends are not just shaping how supply chains operate but are also creating new opportunities and challenges.

AI/ML for Predictive Analytics and Risk Management

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are rapidly transforming supply chain management by enabling more sophisticated predictive analytics and proactive risk management. These technologies can analyze vast amounts of data from diverse sources – including historical sales, weather patterns, social media trends, news reports, and IoT sensor data – to generate more accurate demand forecasts, identify potential disruptions, and optimize various supply chain processes. For instance, AI can predict equipment failures in manufacturing or transportation, allowing for preventative maintenance and minimizing downtime. Early adopters of AI-enabled SCM have reported significant reductions in logistics costs and improvements in inventory levels and service.

In risk management, AI and ML algorithms can continuously monitor global events, supplier financial health, and transportation routes to identify and assess potential risks in real-time. This allows organizations to develop more robust contingency plans and respond more quickly to disruptions. For example, AI can help in mapping multi-tier supply chains to understand hidden dependencies and vulnerabilities that might not be apparent through traditional methods. As companies increasingly experiment with and implement Generative AI, its ability to process information and automate tasks in procurement, supplier management, and logistics is expected to deliver significant value.

However, the adoption of AI also brings challenges, including the need for high-quality data, significant initial investment, and concerns about job displacement, although many experts believe AI will augment human roles and create new opportunities. The focus is shifting towards leveraging AI to enhance human decision-making rather than complete replacement, requiring upskilling and reskilling of the workforce.

These courses explore the application of analytics and AI in supply chains, reflecting this major trend.

The following topic delves deeper into the role of AI in this field.

Consider exploring McKinsey's insights on future supply chains for more on technology's role.

Blockchain for Transparency and Traceability

Blockchain technology offers significant potential to enhance transparency, traceability, and security within supply chains. By creating a decentralized, immutable ledger, blockchain allows all participants in a supply chain to share and access information about transactions and product movements in a secure and verifiable manner. This can drastically improve the ability to trace products from their origin to the final consumer, which is particularly valuable for industries like food and pharmaceuticals where provenance and authenticity are critical.

The improved traceability offered by blockchain can help in combating counterfeit goods, ensuring compliance with ethical sourcing standards, and managing product recalls more efficiently. For example, a consumer could scan a QR code on a product and see its entire journey through the supply chain, verified by blockchain records. Smart contracts, which are self-executing contracts with the terms of the agreement directly written into code, can automate processes like payments upon confirmed delivery, reducing administrative overhead and speeding up transactions.

While the adoption of blockchain in SCM is still in its earlier stages compared to AI, its ability to build trust among supply chain partners without relying on intermediaries is a powerful proposition. Companies are exploring various use cases, from tracking high-value goods to verifying sustainability claims. The technology can help streamline communication, reduce fraud, and improve overall supply chain efficiency by providing a single, shared source of truth.

These courses touch upon the transformative potential of blockchain in supply chains.

Further insights into blockchain's application can be found in resources like this Forbes Advisor article.

Sustainability Initiatives: Circular Supply Chains and Carbon Footprint Reduction

Sustainability has become a critical priority in Supply Chain Management, driven by increasing consumer awareness, regulatory pressures, and the growing recognition of the business benefits of environmentally and socially responsible practices. Companies are focusing on reducing their environmental impact, ensuring ethical labor practices, and promoting social responsibility throughout their supply chains. This includes initiatives to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, minimize waste, conserve natural resources, and ensure fair treatment of workers.

A key concept gaining traction is the circular supply chain, which moves away from the traditional linear "take-make-dispose" model. Instead, it emphasizes keeping products and materials in use for as long as possible through strategies like reuse, repair, refurbishment, and recycling. This approach not only reduces waste and conserves resources but can also create new value streams and enhance brand reputation. Companies are also increasingly focused on reducing their carbon footprint by optimizing transportation routes, using renewable energy, improving energy efficiency in operations, and adopting greener packaging.

Measuring and reporting on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) performance is becoming standard practice, with many organizations setting ambitious sustainability goals. Supply chain visibility and collaboration with suppliers are crucial for achieving these goals, as a significant portion of a company's environmental and social impact often lies within its extended supply network. Technology, including AI and blockchain, can play a role in tracking sustainability metrics and verifying claims.

These courses focus on the increasingly important area of sustainability within supply chain operations.

These books provide further depth on sustainable SCM practices.

Key topics in this area include:

Resilience Strategies Post-Pandemic (e.g., Nearshoring, Diversification)

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the vulnerabilities of long, complex global supply chains, leading to widespread disruptions. As a result, building supply chain resilience has become a top priority for organizations worldwide. Resilience refers to the ability of a supply chain to prepare for and adapt to unexpected events, and to recover quickly from disruptions. This involves not just reacting to crises but proactively identifying risks and implementing mitigation strategies.

Key resilience strategies being adopted include diversification of sourcing, moving away from single-source dependencies to multiple suppliers, potentially in different geographic regions. Nearshoring (moving production closer to end markets) and regionalization (creating regional supply hubs) are also gaining traction as ways to reduce lead times, lower transportation risks, and improve responsiveness. While cost efficiency remains important, there's a greater willingness to balance it with the need for increased agility and risk mitigation.

Enhanced supply chain visibility, often enabled by digital technologies, is crucial for resilience, allowing companies to better understand their end-to-end networks and anticipate potential bottlenecks. Collaboration and information-sharing with key partners are also vital. According to a McKinsey survey from October 2024, while companies have made progress in areas like dual-sourcing and regionalization, significant gaps remain in identifying and mitigating risks, especially in deeper tiers of the supply network. The focus is on creating supply chains that are not only robust but also flexible enough to adapt to a constantly changing global landscape marked by geopolitical tensions, climate events, and other uncertainties.

These courses address the critical need for managing disruptions and building resilient supply networks.

The following topic is central to these strategies:

Formal Education Pathways in Supply Chain Management

For individuals aiming to build a robust career in Supply Chain Management, a strong educational foundation is often a significant asset. Formal education provides structured learning, theoretical knowledge, and analytical skills that are highly valued by employers. Various pathways exist, from undergraduate degrees to specialized graduate programs and professional certifications, each catering to different career stages and aspirations.

Undergraduate Degrees: Building the Foundation

An undergraduate degree is a common starting point for a career in Supply Chain Management. Many universities offer bachelor's degrees specifically in SCM, Logistics, or Operations Management. These programs typically cover core business principles alongside specialized SCM topics such as procurement, inventory management, transportation, warehousing, and supply chain analytics. Students learn quantitative methods, strategic thinking, and problem-solving skills applicable to real-world supply chain challenges.

Curricula often include courses in economics, statistics, accounting, information systems, and business law, providing a well-rounded business education. Some programs may also offer opportunities for internships or co-op placements, allowing students to gain practical experience and build professional networks. A bachelor's degree can open doors to entry-level positions such as logistics coordinator, procurement assistant, supply chain analyst, or inventory planner.

Even if a university doesn't offer a dedicated SCM major, degrees in related fields like business administration (with a concentration in operations or logistics), industrial engineering, or even data analytics can provide a strong foundation. The key is to select coursework that develops analytical capabilities, understanding of business processes, and knowledge of information technology relevant to supply chains. According to Zippia, a business major is the most common among logisticians.

These foundational courses offer an excellent starting point for understanding the core principles of supply chain management, suitable for those beginning their educational journey or looking to solidify their understanding.

A foundational book can complement undergraduate studies effectively.

Graduate Programs: Specialization and Advancement

For those seeking to deepen their expertise, advance to leadership roles, or transition into SCM from another field, graduate programs offer specialized knowledge and skills. A Master of Business Administration (MBA) with a specialization in Supply Chain Management is a popular option. MBA programs provide a broad management education, covering strategy, finance, marketing, and leadership, while the SCM specialization offers in-depth courses on advanced supply chain topics, strategic sourcing, global logistics, and supply chain risk management.

Alternatively, specialized master's degrees, such as a Master of Science in Supply Chain Management (MS-SCM) or Logistics, provide a more focused and intensive study of the field. These programs often delve deeper into quantitative analysis, supply chain modeling, technology applications, and emerging trends like sustainability and digitalization. They are well-suited for individuals who want to become experts in specific SCM domains.

Graduate programs typically involve case studies, research projects, and sometimes industry collaborations, providing opportunities to apply theoretical knowledge to complex business problems. A master's degree can significantly enhance career prospects, leading to roles such as supply chain manager, operations manager, logistics director, or consultant, and often results in higher earning potential.

These courses, offered at a more advanced level, align well with the depth of study found in graduate programs.

A comprehensive textbook is often a cornerstone of graduate-level SCM education.

Professional Certifications: Validating Expertise

Professional certifications are a valuable way for SCM professionals to validate their knowledge and skills, enhance their credibility, and improve their career opportunities. Several globally recognized certifications cater to different areas of supply chain management. These certifications typically require passing one or more rigorous exams and often have experience and/or education prerequisites.

Some of the most well-known certifications include the Certified Supply Chain Professional (CSCP) and Certified in Planning and Inventory Management (CPIM) offered by ASCM (Association for Supply Chain Management, formerly APICS). CSCP covers end-to-end supply chain management, while CPIM focuses on production and inventory management. Another notable certification is the Certified Professional in Logistics (CPL) or similar credentials focusing on logistics expertise. Six Sigma certifications (Green Belt, Black Belt) are also highly valued in SCM for their focus on process improvement and quality management.

Pursuing certifications can be beneficial for both new entrants and experienced professionals. For those starting, it can demonstrate commitment and foundational knowledge. For experienced individuals, it can help in staying updated with best practices and advancing to more senior roles. Many employers recognize and value these credentials, and they can sometimes lead to higher salaries and better job prospects. Some online courses also prepare learners for these certification exams.

These courses are specifically designed to help individuals prepare for SCM certification exams or offer a certified level of knowledge.

Exploring various SCM certifications can help individuals identify the best fit for their career goals.

Research Opportunities in PhD Programs

For those inclined towards academia, research, or high-level consultancy and thought leadership in Supply Chain Management, pursuing a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) is the typical pathway. PhD programs in SCM, Operations Management, or Industrial Engineering involve rigorous research, advanced coursework in theory and quantitative methods, and the development of a dissertation that contributes new knowledge to the field.

Research in SCM is diverse and can cover a wide range of topics, including supply chain optimization, risk and resilience modeling, sustainable supply chains, behavioral operations management, the impact of new technologies like AI and blockchain, humanitarian logistics, and global supply network design. PhD candidates work closely with faculty advisors, publish in academic journals, and present their research at conferences. This path requires a strong analytical aptitude, intellectual curiosity, and a passion for solving complex problems.

A PhD in SCM can lead to a career as a university professor, conducting research and teaching the next generation of supply chain professionals. It can also open doors to roles in research institutions, government agencies, or specialized consulting firms that require deep expertise and analytical capabilities. While it's a demanding path, it offers the opportunity to make significant contributions to the advancement of supply chain knowledge and practice.

While specific PhD-level courses are not listed, advanced courses focusing on specific research methodologies or cutting-edge topics can be found by browsing specialized university offerings. For instance, OpenCourser allows users to browse business courses, which can include advanced seminars and research-oriented modules. Exploring the Industrial Engineering category might also yield relevant advanced topics.

Online and Self-Directed Learning in Supply Chain Management

In today's rapidly evolving job market, online and self-directed learning pathways offer flexible and accessible options for individuals looking to enter or advance in the field of Supply Chain Management. These routes can be particularly appealing for career changers, working professionals seeking to upskill, or curious learners wanting to explore the domain without the commitment of a full-time degree program. OpenCourser is an excellent platform to find a wide array of SCM courses to suit various learning needs.

Feasibility of Self-Study for Entry-Level Roles

It is indeed feasible to prepare for certain entry-level roles in Supply Chain Management through dedicated self-study and online courses. Many foundational concepts in logistics, procurement, inventory basics, and customer service can be effectively learned through well-structured online programs. These roles might include positions like logistics coordinator, dispatch clerk, purchasing assistant, or inventory clerk, where practical understanding and specific skills are highly valued.

To make self-study effective, it's important to be disciplined and create a structured learning plan. Focus on acquiring a solid understanding of core SCM principles, common terminology, and relevant software tools (like basic Excel for supply chain tasks or introductory modules to ERP systems). Supplementing theoretical learning with practical case studies, simulations, or even volunteer work in a related area can significantly enhance your profile. While a formal degree might be preferred by some employers, demonstrating initiative, a strong grasp of fundamentals, and relevant skills through a portfolio of completed courses or projects can make a compelling case for entry-level positions, especially in smaller companies or for specific operational roles.

Remember, persistence is key. The journey of self-study requires motivation and a proactive approach to fill knowledge gaps. Networking with professionals in the field, even virtually, can also provide valuable insights and potential opportunities. While some employers might still prioritize traditional degrees, a well-curated set of skills and knowledge acquired through self-study can certainly open doors.

These courses are excellent for building foundational knowledge, making them suitable for self-study towards entry-level roles.

A good introductory book can guide self-study efforts.

Blending Online Courses with Hands-On Projects

One of the most effective ways to leverage online learning for SCM is to blend theoretical knowledge gained from courses with practical, hands-on projects. This approach helps solidify understanding, develop problem-solving skills, and create tangible evidence of your capabilities for potential employers. Many online SCM courses now include simulations, case studies, or project assignments that mimic real-world challenges.

For instance, you could use skills learned in an inventory management course to create a simulation of an inventory system for a small business, perhaps using spreadsheet software to model different reorder points and safety stock levels. If learning about logistics, you might analyze different transportation routes for a hypothetical company, considering costs, lead times, and risk factors. Some learners even take on freelance micro-projects or volunteer to help local non-profits with their supply chain tasks to gain experience.

Creating a portfolio of these projects, detailing the problem, your approach, the tools used, and the outcomes, can be a powerful asset in a job search. It demonstrates not only what you've learned but also your ability to apply that knowledge. Platforms like OpenCourser often feature courses with built-in projects or suggest supplementary activities, and their Learner's Guide can offer tips on how to structure such learning experiences effectively.

These courses provide practical knowledge that can be directly applied to hands-on projects.

This book offers practical insights that can inspire project ideas.

Micro-Credentials for Niche Topics

Micro-credentials, such as certificates for completing a series of specialized online courses or a focused program, are becoming increasingly popular for gaining expertise in niche SCM topics. These can be particularly valuable for professionals looking to upskill in emerging areas like blockchain in SCM, sustainable supply chains, supply chain analytics with AI, or e-commerce logistics. They offer a more targeted and often quicker way to acquire specific skills compared to a full degree program.

For example, a procurement specialist might pursue a micro-credential in ethical sourcing, or a logistics manager might take a series of courses on cold chain logistics if their company is expanding into perishable goods. These credentials can signal to employers that you are proactive in your professional development and possess up-to-date knowledge in specialized domains. They can also be useful for career pivots, allowing individuals to gain credible qualifications in a new area of SCM without committing to a lengthy program.

When choosing micro-credentials, consider the reputation of the issuing institution or platform, the relevance of the curriculum to your career goals, and whether the program includes practical application or project work. OpenCourser's "Save to list" feature can be helpful for shortlisting and comparing such programs as you explore options like Logistics or specialized areas within Business.

These courses focus on specific, niche areas within SCM, making them ideal for micro-credentialing or specialization.

Relevant topics for specialized learning include:

Supplementing Formal Education with Specialized Modules

Online courses and specialized modules offer an excellent way for students currently enrolled in formal education programs (like a bachelor's or master's degree) to supplement their learning and gain deeper knowledge in specific areas of SCM. University curricula, while comprehensive, may not always cover the very latest trends or highly specialized tools in great depth. Online platforms can fill these gaps by providing access to cutting-edge content from industry experts and leading academics worldwide.

For example, a student in a general business program might take an online module on supply chain risk management to complement their operations management coursework. Similarly, an industrial engineering student could explore online courses on AI applications in logistics or advanced warehouse automation to gain a competitive edge. This approach allows students to tailor their learning to their specific interests and career aspirations, making them more well-rounded and attractive to potential employers.

Furthermore, many online courses offer certificates of completion, which can be added to a resume or LinkedIn profile to showcase specialized knowledge. It's a proactive way to demonstrate a commitment to continuous learning and a passion for the SCM field. When selecting supplementary modules, ensure they align with your foundational knowledge and enhance, rather than simply repeat, what you are learning in your formal program. OpenCourser's detailed course descriptions and syllabi (where available) can help in making these choices.

These courses can provide specialized knowledge to supplement formal degree programs.

This topic focuses on an important specialized area:

Career Progression in Supply Chain Management

A career in Supply Chain Management offers diverse opportunities for growth and advancement. The field is critical to almost every industry, leading to a consistent demand for skilled professionals. Progression typically involves moving from operational and analytical roles to managerial and strategic leadership positions. Understanding the potential career trajectory, along with the skills and experience required at each stage, can help individuals plan their professional development effectively.

Entry-Level Roles: Gaining Foundational Experience

Entry-level positions in SCM are crucial for building a solid foundation of practical experience and understanding the day-to-day operations of a supply chain. Common roles include Logistics Coordinator, Procurement Assistant, Supply Chain Analyst (junior level), Inventory Planner, or Dispatcher. In these roles, individuals typically support more senior staff, handle operational tasks, collect and analyze data, and learn the specific processes and systems used by their organization.

A Logistics Coordinator might be involved in tracking shipments, coordinating with carriers, and ensuring timely deliveries. A Procurement Assistant could help with sourcing suppliers, processing purchase orders, and managing supplier documentation. An entry-level Supply Chain Analyst often focuses on gathering data, generating reports, and assisting with basic forecasting or inventory analysis. These roles provide exposure to different facets of the supply chain and help develop essential skills in problem-solving, communication, and using SCM software. While some roles may be accessible with an associate's degree or relevant certifications, a bachelor's degree in SCM, logistics, business, or a related field is often preferred or required for analyst positions. According to ASCM, the median salary for a Demand Planner (often an early-career role) was $78,375 and for a Supply Chain Analyst was $78,400 in 2023.

This phase is about learning the ropes, demonstrating reliability, and developing a keen eye for detail and efficiency. It's also an excellent time to identify areas within SCM that are of particular interest for future specialization. Many professionals find that practical experience gained in these initial roles is invaluable throughout their careers.

These courses can help build the analytical and operational skills needed for entry-level SCM roles.

Consider these entry-to-mid-level career paths:

Mid-Career Paths: Specialization and Management

After gaining several years of foundational experience, SCM professionals often move into mid-career roles that involve greater responsibility, specialization, and often, team leadership. Titles at this stage can include Supply Chain Manager, Operations Manager, Logistics Manager, Procurement Manager, Inventory Manager, or Senior Supply Chain Analyst. These roles typically require a deeper understanding of specific SCM functions, strong analytical and problem-solving skills, and the ability to manage projects and people.

A Supply Chain Manager oversees broader aspects of the supply chain, developing strategies, managing budgets, and improving overall performance. An Operations Manager might be responsible for a manufacturing plant or distribution center, focusing on efficiency, quality, and cost control. A Logistics Manager handles transportation, warehousing, and distribution networks, while a Procurement Manager leads sourcing activities and supplier relationships. According to ASCM's 2023 report, median salaries for such roles included Purchasing Manager ($90,000), Inventory Manager ($93,000), Logistics Manager ($100,000), Procurement Manager ($104,000), Materials Manager ($110,342), and Supply Chain Manager ($114,750). Salary.com reported an average annual salary for a Supply Chain Manager in the US as $125,505 as of May 2025, with ranges often between $113,707 and $138,477. ZipRecruiter data from April 2025 indicated an average of around $100,315 for Supply Chain Managers. Talent.com also suggests an average around $100,075, with experienced workers earning up to $165,000.

At this stage, continuous learning and professional development, such as obtaining relevant certifications (e.g., CSCP, CPIM) or pursuing a master's degree, can be highly beneficial for career advancement. Strong leadership, communication, and strategic thinking skills become increasingly important. Professionals often specialize in areas like global logistics, strategic sourcing, demand planning, or SCM technology implementation.

These courses are suited for professionals looking to advance into mid-career SCM roles, focusing on strategy and broader management skills.

A pivotal role in this stage is:

Books focusing on strategic SCM are very relevant at this career stage.

Leadership Roles: Strategic Oversight and Influence

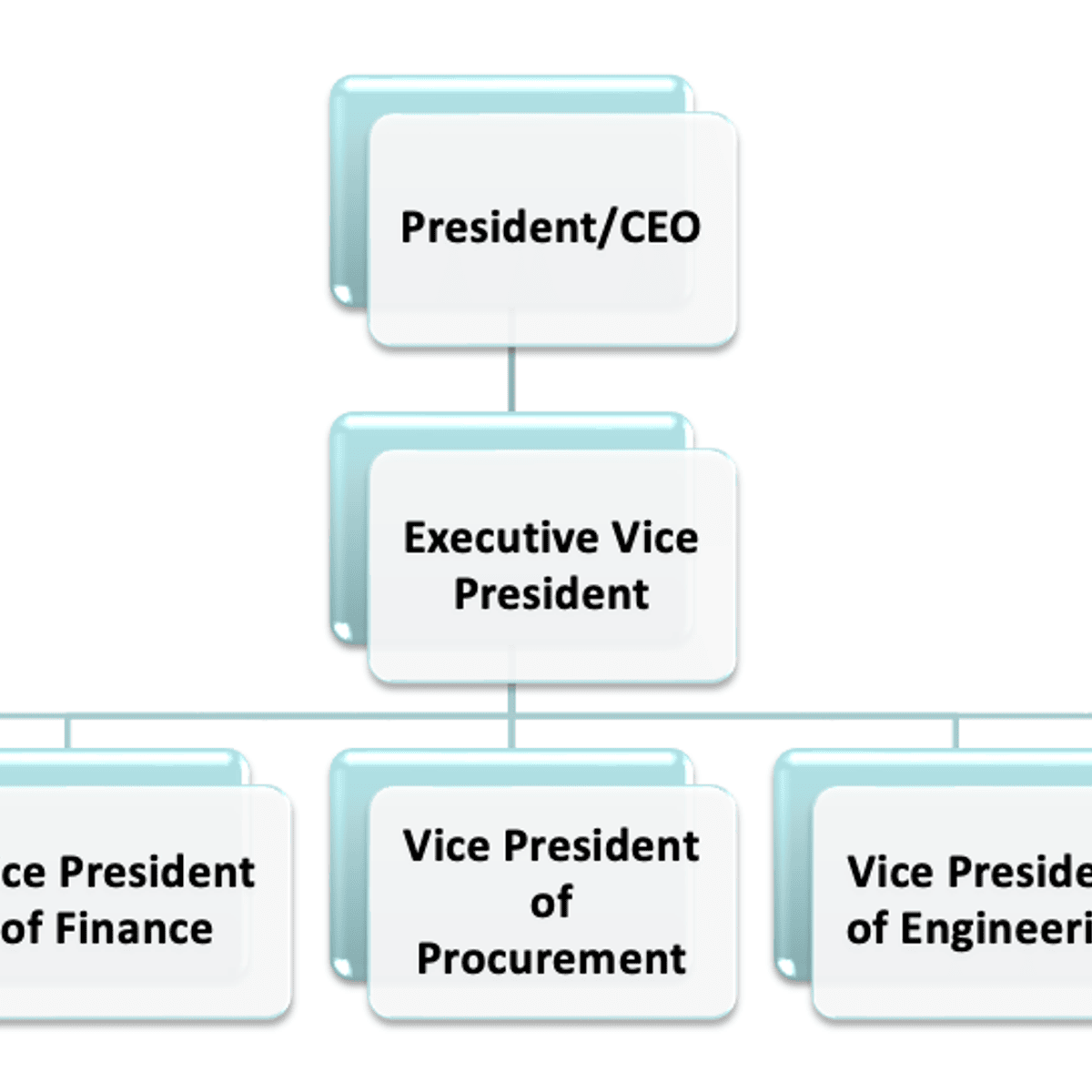

With significant experience and a proven track record, SCM professionals can advance to senior leadership roles. These positions involve setting the strategic direction for the company's entire supply chain, managing large teams and budgets, and influencing key business decisions. Common titles include Director of Supply Chain, Vice President (VP) of Supply Chain, Chief Supply Chain Officer (CSCO), or Chief Operations Officer (COO).

In these roles, individuals are responsible for optimizing the end-to-end supply chain to achieve business objectives related to cost, service, quality, resilience, and sustainability. They work closely with other C-suite executives to align supply chain strategy with overall business strategy. Leadership roles require exceptional strategic thinking, decision-making, negotiation, and change management skills. A deep understanding of global markets, emerging technologies, risk management, and sustainability practices is essential. According to ASCM's 2023 data, Supply Chain Directors earned a median salary of $145,000, with top earners in leadership making over $192,000 when including bonuses and other compensation.

Many executives in these positions hold advanced degrees (like an MBA or specialized master's) and have extensive experience across various SCM functions and industries. They are often responsible for driving innovation, leading digital transformation initiatives, and building agile and resilient supply chains that can navigate an increasingly complex and volatile global environment. The job outlook for logisticians and supply chain managers, in general, is positive, with projected growth much faster than the average for all occupations, indicating continued demand for skilled leaders. The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects employment for logisticians to grow 19 percent from 2023 to 2033.

For those aspiring to leadership, courses focusing on high-level strategy and comprehensive management are key.

A leadership role to aim for is:

Cross-Functional Mobility: Expanding Horizons

The skills and experience gained in Supply Chain Management are highly transferable, offering opportunities for cross-functional mobility into related fields. SCM professionals develop strong analytical, problem-solving, project management, and negotiation skills, which are valued in many different roles and industries. This versatility can lead to exciting career pivots and broader professional development.

One common transition is into management consulting. SCM consultants work with various clients to help them improve their supply chain performance, implement new technologies, or redesign their operations. The ability to quickly understand complex business problems, analyze data, and develop actionable recommendations is a key asset. Another area is operations management, which often has significant overlap with SCM but may focus more broadly on the internal processes of a company, including manufacturing, service delivery, and quality control. SCM professionals may also move into roles in project management, business analysis, or even general management, leveraging their understanding of how different parts of a business connect and operate.

Furthermore, with the increasing importance of data analytics in SCM, individuals with strong quantitative skills might find opportunities in data science or business intelligence roles, focusing on supply chain data. The experience of managing global networks, dealing with international trade, and navigating cultural differences can also be valuable for roles in international business development or global strategy. This cross-functional mobility underscores the broad applicability and strategic importance of supply chain expertise in today's interconnected business world.

These courses highlight skills that are highly transferable to consulting and broader operational roles.

A relevant career pivot could be:

This broader topic encompasses many skills used in SCM.

Ethical Challenges in Supply Chain Management

As global supply chains become increasingly complex and geographically dispersed, they also face a growing number of ethical challenges. These challenges require careful consideration and proactive management to ensure that business operations are conducted responsibly and sustainably. Addressing these issues is not only a matter of corporate social responsibility but also increasingly important for brand reputation, legal compliance, and long-term business viability.

Labor Practices and Human Rights in Global Supply Chains

One of the most significant ethical challenges in SCM revolves around labor practices and human rights, particularly in developing countries where many goods are manufactured. Issues such as forced labor, child labor, unsafe working conditions, excessive working hours, and unfair wages can be prevalent in some parts of global supply chains. Companies sourcing from these regions face the risk of being associated with such abuses, which can lead to severe reputational damage, consumer boycotts, and legal repercussions.

Ensuring ethical labor practices requires robust supplier codes of conduct, regular audits, and transparency throughout the supply chain. However, visibility into lower-tier suppliers (suppliers of suppliers) can be difficult to achieve. Companies are increasingly expected to take responsibility for conditions not just in their direct suppliers' factories but further down the chain. This involves working collaboratively with suppliers to improve standards, investing in training and capacity building, and sometimes making difficult decisions about disengaging with suppliers who fail to meet ethical requirements.

Technology, such as blockchain, is being explored as a means to improve traceability and verify claims about labor conditions, but human oversight and commitment remain crucial. Advocacy groups and international organizations play a vital role in highlighting these issues and pressuring companies to improve. For SCM professionals, navigating these complexities requires a strong ethical compass and a commitment to upholding human rights.

Courses that touch on sustainability and global operations often cover ethical labor practices.

Understanding corporate social responsibility is key.

Environmental Impact of Logistics Networks

The logistics component of supply chains, particularly transportation and warehousing, has a significant environmental impact. Transportation of goods, whether by road, sea, air, or rail, is a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution. Warehousing operations also consume energy for lighting, heating, cooling, and material handling equipment. Packaging waste is another major environmental concern associated with the movement and distribution of products.

Addressing these environmental impacts requires a multi-faceted approach. This includes optimizing transportation routes to reduce mileage and fuel consumption, shifting to more fuel-efficient modes of transport (e.g., from air to sea or rail where feasible), and investing in cleaner vehicle technologies like electric trucks. In warehousing, adopting energy-efficient designs, using renewable energy sources, and implementing waste reduction programs are important steps. Sustainable packaging solutions, such as using recycled materials, reducing packaging size, and designing for reusability, also play a crucial role.

Companies are increasingly being held accountable for the carbon footprint of their supply chains. Regulatory measures like carbon taxes or emissions trading schemes, along with consumer demand for greener products and services, are driving the adoption of more sustainable logistics practices. SCM professionals need to be knowledgeable about these environmental issues and capable of implementing strategies to minimize the ecological footprint of their operations.

These courses delve into sustainable practices, including reducing environmental impact.

This book focuses on a key aspect of logistics impact.

The following topic is central to these concerns.

Counteracting Counterfeit Goods and Fraud

The proliferation of counterfeit goods and various forms of fraud pose significant ethical and economic challenges to supply chains. Counterfeiting affects a wide range of industries, from luxury goods and pharmaceuticals to electronics and automotive parts. Fake products can not only lead to financial losses for legitimate businesses but also pose serious health and safety risks to consumers, especially in the case of counterfeit medicines or substandard components.

Fraud in supply chains can take many forms, including invoice fraud, cargo theft, and corruption in procurement processes. These activities undermine the integrity of the supply chain, increase costs, and can damage a company's reputation. Combating counterfeiting and fraud requires robust security measures, enhanced traceability, and close collaboration with law enforcement and industry partners.

Technologies like blockchain are being explored for their potential to improve product authentication and traceability, making it harder for counterfeit goods to enter legitimate supply chains. Secure packaging, serialization, and RFID tagging are other tools used to track products and verify their authenticity. SCM professionals must be vigilant in identifying potential vulnerabilities in their supply chains and implementing measures to prevent and detect fraudulent activities. This includes thorough vetting of suppliers and partners, implementing strong internal controls, and fostering a culture of ethics and compliance.

Courses focusing on transparency and technology can be relevant here.

Understanding supply chain security is crucial in this context.

Balancing Cost Efficiency with Ethical Sourcing

A persistent ethical dilemma in SCM is the tension between the drive for cost efficiency and the imperative of ethical sourcing. Companies are often under pressure to reduce costs to remain competitive, which can lead to sourcing from suppliers in regions with lower labor and environmental standards. While this may offer short-term financial benefits, it can create significant ethical risks and long-term sustainability challenges.

Ethical sourcing involves ensuring that products and materials are obtained in a responsible and sustainable way, that workers involved are treated fairly and safely, and that environmental impacts are minimized. This often requires investing more in supplier selection, auditing, and development, which can sometimes increase upfront costs. However, many companies are recognizing that the long-term benefits of ethical sourcing – including enhanced brand reputation, improved customer loyalty, reduced risk of disruptions, and greater employee morale – outweigh the short-term cost considerations.

Achieving a balance requires a strategic approach that integrates ethical considerations into all procurement and supply chain decisions. This includes a willingness to pay a fair price for goods produced under ethical conditions and to collaborate with suppliers to improve standards rather than simply switching to the cheapest option. Transparency and communication with stakeholders about sourcing practices are also increasingly important. SCM professionals play a critical role in navigating this balance, making decisions that are both economically sound and ethically responsible.

Courses on sourcing and sustainability address this balance.

Global Supply Chain Dynamics

Global supply chains operate within a complex and ever-changing international landscape. Various macro-level factors, including geopolitical events, cultural nuances, and regional infrastructure capabilities, can significantly influence the efficiency, cost, and resilience of these networks. Understanding these dynamics is essential for financial analysts assessing market stability and for international practitioners managing cross-border operations.

Geopolitical Risks (e.g., Trade Wars, Tariffs, Conflicts)

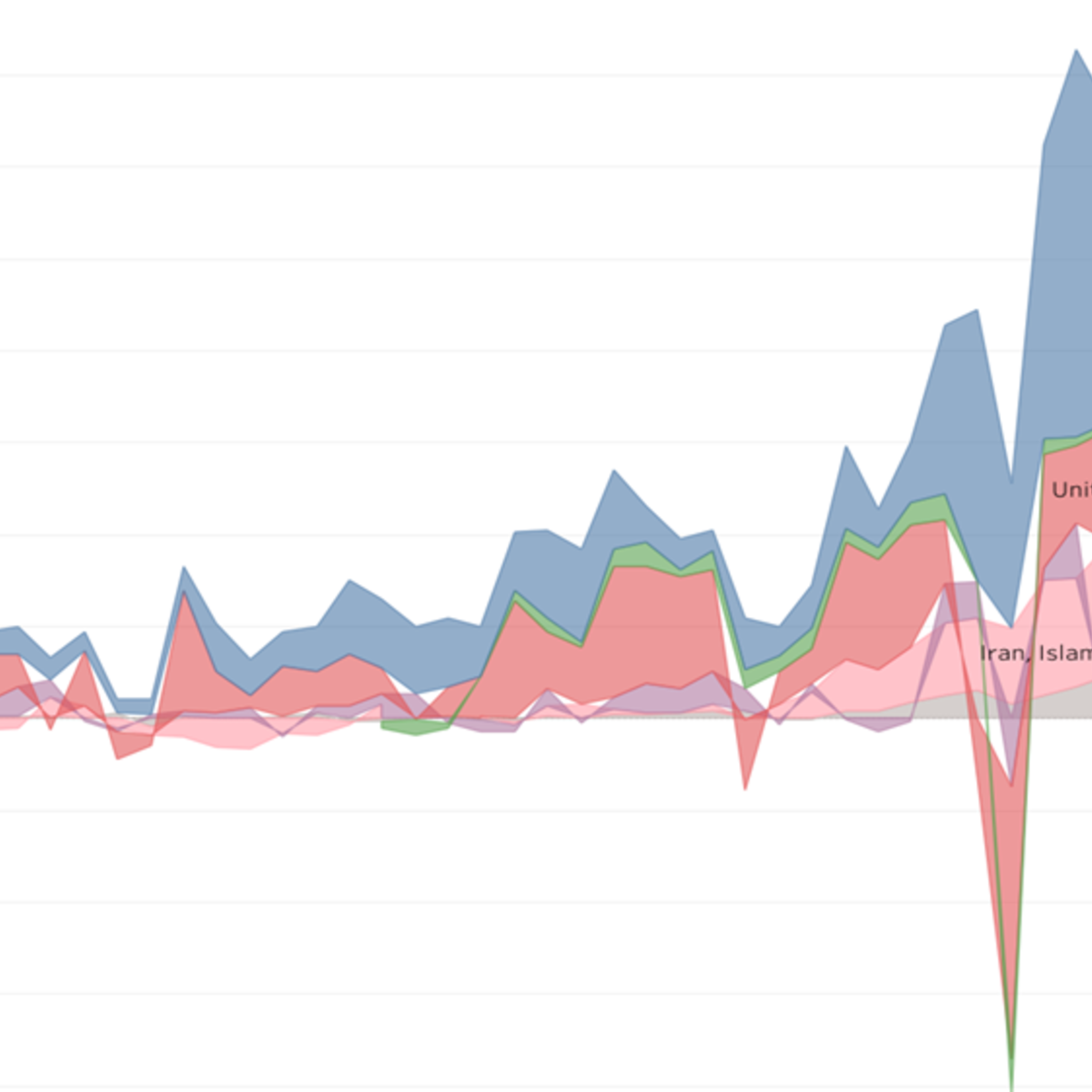

Geopolitical risks, such as trade wars, the imposition of tariffs, economic sanctions, and armed conflicts, represent significant challenges to global supply chains. These events can disrupt the flow of goods, increase costs, and create uncertainty for businesses. For example, tariffs on imported goods can make components or finished products more expensive, forcing companies to either absorb the costs, pass them on to consumers, or reconfigure their supply chains to source from different locations. Political instability or conflicts in key regions can lead to port closures, disruptions in transportation routes, and even the shutdown of manufacturing facilities, impacting the availability of critical materials and products.

The COVID-19 pandemic, and more recently, conflicts like the war in Ukraine, have highlighted the vulnerability of global supply chains to such shocks. These events have prompted many companies to reassess their reliance on specific countries or regions and to explore strategies for building greater resilience, such as diversifying their supplier base or nearshoring production. Navigating these geopolitical risks requires constant monitoring of the global political and economic environment, scenario planning, and developing agile supply chain strategies that can adapt to changing conditions. As noted in a report by the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS), businesses are increasingly rethinking the value of lean, globally distributed supply chains in favor of models that prioritize reliability and resilience.

The increasing frequency of such events means that geopolitical risk management has become a core competency for global supply chain managers. This involves not only reacting to crises but also proactively identifying potential flashpoints and building contingency plans to mitigate their impact.

These courses can provide context on international business operations and managing global risks.

Key topics relevant to this include:

Cultural Considerations in Supplier Negotiations

When operating globally, cultural differences can play a significant role in supplier negotiations and relationship management. Business practices, communication styles, approaches to decision-making, and perceptions of time can vary widely across cultures. Ignoring these differences can lead to misunderstandings, strained relationships, and ultimately, less effective supply chain partnerships.

For instance, in some cultures, building a personal relationship and trust is a prerequisite for conducting business, requiring more time and social interaction before substantive negotiations begin. In other cultures, a more direct, task-oriented approach is common. Negotiation styles can also differ, with some cultures valuing assertiveness and direct confrontation, while others prefer indirect communication and consensus-building. Understanding these nuances is crucial for successful cross-cultural negotiations and for fostering long-term, collaborative supplier relationships.

Effective global supply chain managers invest time in learning about the cultures of their key suppliers and adapt their communication and negotiation strategies accordingly. This might involve using interpreters, being mindful of non-verbal cues, and showing respect for local customs and traditions. Building cultural intelligence within the SCM team can lead to smoother negotiations, stronger partnerships, and a more resilient and adaptive global supply network.

While not SCM-specific, courses on international business or cross-cultural communication can be very beneficial for understanding these dynamics. OpenCourser offers a variety of courses in Communication Studies and International Studies which may cover relevant aspects.

Regional Infrastructure Disparities

The quality and availability of infrastructure – including transportation networks (roads, railways, ports, airports), communication systems, and energy supply – vary significantly across different regions and countries. These disparities can have a profound impact on the efficiency, cost, and reliability of supply chain operations. Sourcing from or distributing to regions with underdeveloped infrastructure can lead to longer lead times, higher transportation costs, increased risk of damage to goods, and greater operational complexity.

For example, poor road conditions can slow down truck transport and increase vehicle maintenance costs. Inefficient port operations can lead to significant delays in loading and unloading cargo. Unreliable electricity supply can disrupt manufacturing processes. Conversely, regions with well-developed, modern infrastructure can offer significant advantages in terms of speed, cost, and reliability, making them more attractive locations for sourcing, manufacturing, or distribution hubs.

When designing global supply chain networks, companies must carefully assess the infrastructure capabilities of different regions. This involves considering not only the current state of infrastructure but also planned investments and potential risks (e.g., vulnerability to natural disasters). Strategies to mitigate infrastructure-related challenges might include investing in alternative transportation modes, building buffer inventory, or even collaborating with local authorities or other businesses to improve infrastructure.

These courses touch on the design and operational aspects where infrastructure plays a critical role.

Case Studies: Semiconductor Shortages and Automotive Industries

Recent events have provided stark case studies on the impact of global dynamics on specific industries. The global semiconductor shortage, which began to significantly impact various sectors in 2020 and 2021, is a prime example. Semiconductors are essential components in a vast array of products, from consumer electronics and automobiles to industrial machinery and medical devices. The shortage was caused by a confluence of factors, including a surge in demand for electronics during the pandemic, disruptions to production due to COVID-19 outbreaks and extreme weather events, and existing geopolitical tensions affecting key manufacturing regions. The automotive industry was particularly hard-hit, with many manufacturers forced to halt production lines due to a lack of chips, leading to significant revenue losses and delays in vehicle deliveries.

The automotive supply chain itself is a complex global network, traditionally optimized for lean manufacturing and just-in-time delivery. This made it highly vulnerable to disruptions like the semiconductor shortage. The crisis prompted a re-evaluation of sourcing strategies within the industry, with a greater focus on building resilience, improving visibility into lower-tier suppliers, and in some cases, exploring direct partnerships with chip manufacturers. It also highlighted the strategic importance of semiconductors and led to government initiatives in various countries aimed at boosting domestic chip production and reducing reliance on a few concentrated sources of supply.

These case studies illustrate how interconnected global supply chains are and how disruptions in one part of the world or in one component category can have cascading effects across multiple industries and economies. They underscore the need for robust risk management, strategic diversification, and greater visibility and collaboration across global supply networks.

Understanding specific industry dynamics is crucial. This course focuses on the automotive sector.

Further exploration of industry-specific SCM can be beneficial.

Frequently Asked Questions about Supply Chain Management

Embarking on a career or educational path in Supply Chain Management often brings up a host of questions. Here, we address some of the common inquiries to provide clarity and help you make informed decisions about this dynamic and vital field.

Is a degree mandatory for entry-level roles?

While a bachelor's degree in supply chain management, logistics, business, or a related field is increasingly common and often preferred for many entry-level roles, particularly analytical positions, it is not always an absolute mandate for all starting positions. Some operational roles, such as logistics coordinator, warehouse associate, or dispatch clerk, may be accessible with an associate's degree, relevant certifications, or significant practical experience, especially in smaller companies. Demonstrating strong foundational knowledge through online courses, possessing relevant technical skills (like proficiency in Excel or familiarity with SCM software), and showcasing a proactive learning attitude can also strengthen an application. However, for broader career advancement and access to more strategic roles, a bachelor's degree generally provides a significant advantage.

How does SCM differ from operations management?

Supply Chain Management (SCM) and Operations Management (OM) are closely related and often overlapping fields, but they have distinct focuses. Operations Management is primarily concerned with managing the processes that transform inputs (like materials, labor, and energy) into outputs (goods and services) *within* an organization. It focuses on efficiency, quality, and productivity in areas like manufacturing, service delivery, and internal logistics.

Supply Chain Management, on the other hand, takes a broader, more external view. It encompasses the planning and management of all activities involved in sourcing, procurement, conversion, and logistics management *across* multiple organizations. SCM focuses on the entire flow of goods, services, information, and finances from the initial supplier to the ultimate consumer. While OM might optimize a single factory's output, SCM looks at how that factory integrates with suppliers upstream and distributors and customers downstream to create an efficient and responsive end-to-end system. Essentially, OM is a critical component of SCM, but SCM has a wider, inter-organizational scope.

These courses can help clarify the distinctions and overlaps:

What industries hire the most SCM professionals?

Supply Chain Management professionals are in demand across a vast array of industries because virtually every organization that produces or delivers goods or services has a supply chain. However, some sectors have a particularly high concentration of SCM roles. These include manufacturing (of all types, from automotive and electronics to consumer packaged goods and industrial equipment), retail (especially with the growth of e-commerce and complex distribution networks), and logistics and transportation services (third-party logistics providers, freight forwarders, shipping companies).

Other significant employers include the healthcare sector (managing supplies for hospitals and pharmaceutical distribution), aerospace and defense, the energy sector, agriculture and food production, and government agencies (particularly in defense logistics and public procurement). The rise of e-commerce has created a surge in demand for SCM professionals skilled in fulfillment, last-mile delivery, and warehouse automation. Essentially, any industry with complex sourcing, production, and distribution needs will require skilled SCM talent.

Can certifications replace experience for SCM roles?

Professional certifications like CSCP or CPIM can significantly enhance a candidate's profile and demonstrate a commitment to the SCM field, but they generally do not fully replace practical experience, especially for roles requiring significant decision-making or leadership. Certifications are excellent for validating knowledge, learning best practices, and can be a strong asset for entry-level candidates or those looking to specialize or advance.

However, employers often look for a combination of theoretical understanding (which certifications help demonstrate) and the ability to apply that knowledge in real-world situations (which comes from experience). For entry-level roles, a strong certification might help a candidate stand out, particularly if their formal education is in a less directly related field. For mid-career and senior roles, certifications are often seen as a valuable supplement to a solid track record of experience and accomplishments. In essence, certifications and experience are complementary, not mutually exclusive, in building a successful SCM career.

These courses prepare individuals for well-regarded SCM certifications.

How vulnerable are SCM careers to automation and AI?

Automation and Artificial Intelligence (AI) are indeed transforming Supply Chain Management, automating many routine tasks and enhancing decision-making capabilities. Tasks like data entry, basic report generation, and some aspects of inventory tracking are becoming increasingly automated. AI is also being used for demand forecasting, route optimization, and predictive maintenance. This does mean that some traditional SCM roles, particularly those focused on repetitive, manual tasks, may evolve or see reduced demand.

However, most experts believe that AI and automation will augment rather than entirely replace SCM professionals. The technology will free up humans to focus on more strategic, complex, and value-added activities, such as managing exceptions, fostering supplier relationships, developing innovative solutions, and making nuanced decisions that require human judgment and ethical considerations. New roles are also emerging that require skills in managing and interpreting data from AI systems, designing and implementing automated solutions, and ensuring the ethical use of these technologies. Professionals who are adaptable, willing to upskill in areas like data analytics and technology management, and who can leverage AI as a tool will likely find their careers enhanced, not threatened. Studies suggest that while some jobs will be disrupted, AI is also expected to create new opportunities.

These resources explore the impact of AI on supply chains and related job roles:

What soft skills are most valued in SCM roles?

While technical knowledge and analytical abilities are crucial in Supply Chain Management, soft skills are equally important for success, especially in roles involving collaboration, negotiation, and leadership. Strong communication skills are essential for effectively interacting with suppliers, customers, and internal teams across different departments and often, different cultures. Problem-solving and critical thinking are vital for identifying issues in complex supply chains and developing effective solutions, often under pressure.

Adaptability and flexibility are key, as SCM professionals frequently deal with unexpected disruptions and must be able to adjust plans quickly. Negotiation skills are paramount in procurement and supplier management for achieving favorable terms and building strong partnerships. Attention to detail is critical for ensuring accuracy in areas like inventory management, order fulfillment, and compliance. Furthermore, leadership and teamwork skills become increasingly important as one moves into managerial roles, requiring the ability to motivate teams, manage conflict, and drive collaborative efforts towards common goals. A customer-centric mindset, focusing on meeting and exceeding customer expectations, also underpins successful supply chain operations.

This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of Supply Chain Management. We hope it has supplied you with valuable insights to help you determine if this is the right path for you. The field is dynamic, challenging, and essential to the global economy, offering a wide range of opportunities for those willing to learn and adapt. OpenCourser provides many resources, from browsing logistics courses to exploring deals on educational materials, to support your learning journey.