Music Arranger

Becoming a Music Arranger: Crafting Soundscapes

A Music Arranger takes existing musical material—a melody, a song, a theme—and adapts it for a specific performance setting, ensemble, or style. Think of them as musical architects who design how a piece of music will sound, deciding which instruments play what parts, how harmonies are voiced, and how the overall structure unfolds. Their work shapes the listener's experience, transforming a basic musical idea into a fully realized performance.

Working as an arranger can be deeply fulfilling, involving creative problem-solving and collaboration with composers, performers, and producers. It offers the chance to explore diverse musical genres and instrumental combinations, from crafting intimate acoustic versions to orchestrating large-scale symphonic works. The thrill lies in hearing your arrangement brought to life by talented musicians, adding your unique voice to the musical landscape.

What Does a Music Arranger Do?

Definition and Core Responsibilities

At its core, music arranging involves reinterpreting a musical piece. This isn't composing from scratch, but rather taking an existing composition and tailoring it. An arranger might adapt a pop song for a jazz big band, orchestrate a piano piece for a symphony orchestra, or create a vocal harmony arrangement for an a cappella group.

Key responsibilities include understanding the source material deeply, selecting appropriate instrumentation, writing individual parts for each instrument or voice, and ensuring the arrangement is playable and stylistically coherent. They must balance creative vision with practical considerations like performer skill levels and available resources.

Arrangers often work closely with composers, artists, music directors, or producers to achieve a desired sound. This requires strong communication skills alongside musical expertise. The final product is typically a score and individual parts ready for rehearsal and performance.

This foundational course provides a comprehensive overview of music theory, essential for any aspiring arranger.

Understanding how harmony functions is critical for effective arranging.

Distinction Between Composer and Arranger

While composers create original musical works, arrangers adapt existing ones. A composer originates the melody, harmony, and rhythm that define a piece. An arranger then takes that foundation and reimagines it for a different context.

However, the line can sometimes blur. Arrangers often add creative elements, such as countermelodies, harmonic substitutions, or new formal sections, that significantly shape the final piece. Highly creative arrangements can sometimes be considered derivative works with their own copyright status, depending on the extent of original contribution.

Many musicians work as both composers and arrangers. Understanding composition strengthens arranging skills, and vice versa. Both roles require a deep understanding of music theory, instrumentation, and form, but their starting points differ: one begins with a blank page, the other with existing material.

Exploring composition can deepen an arranger's understanding of musical structure and development.

Historical Evolution of the Role

Music arrangement has existed implicitly for centuries, as performers adapted music for available instruments. However, the role became more formalized with the rise of larger ensembles and the music publishing industry. In the Baroque era, composers often left instrumentation details open, requiring performers or directors to make arranging decisions.

The Classical and Romantic periods saw composers specifying instrumentation more precisely, but arrangements for different forces (like piano reductions of orchestral works) were common for dissemination and study. The 20th century, particularly with the rise of jazz big bands, film scoring, and popular music recording, solidified the arranger as a distinct and crucial creative role.

Figures like Duke Ellington, Nelson Riddle, Gil Evans, and Quincy Jones became celebrated for their arranging prowess, demonstrating how transformative arrangement can be. Today, arrangers work across genres, adapting music for recordings, live performance, film, television, video games, and educational settings, continually evolving with new technologies and musical styles.

Learning about different historical periods provides context for arranging styles.

Key Skills and Competencies

Music Theory and Notation Proficiency

A rock-solid foundation in music theory is non-negotiable for an arranger. This includes understanding harmony, counterpoint, melody, rhythm, and form. You need to analyze the structure and harmonic language of the original piece to make informed decisions about your arrangement.

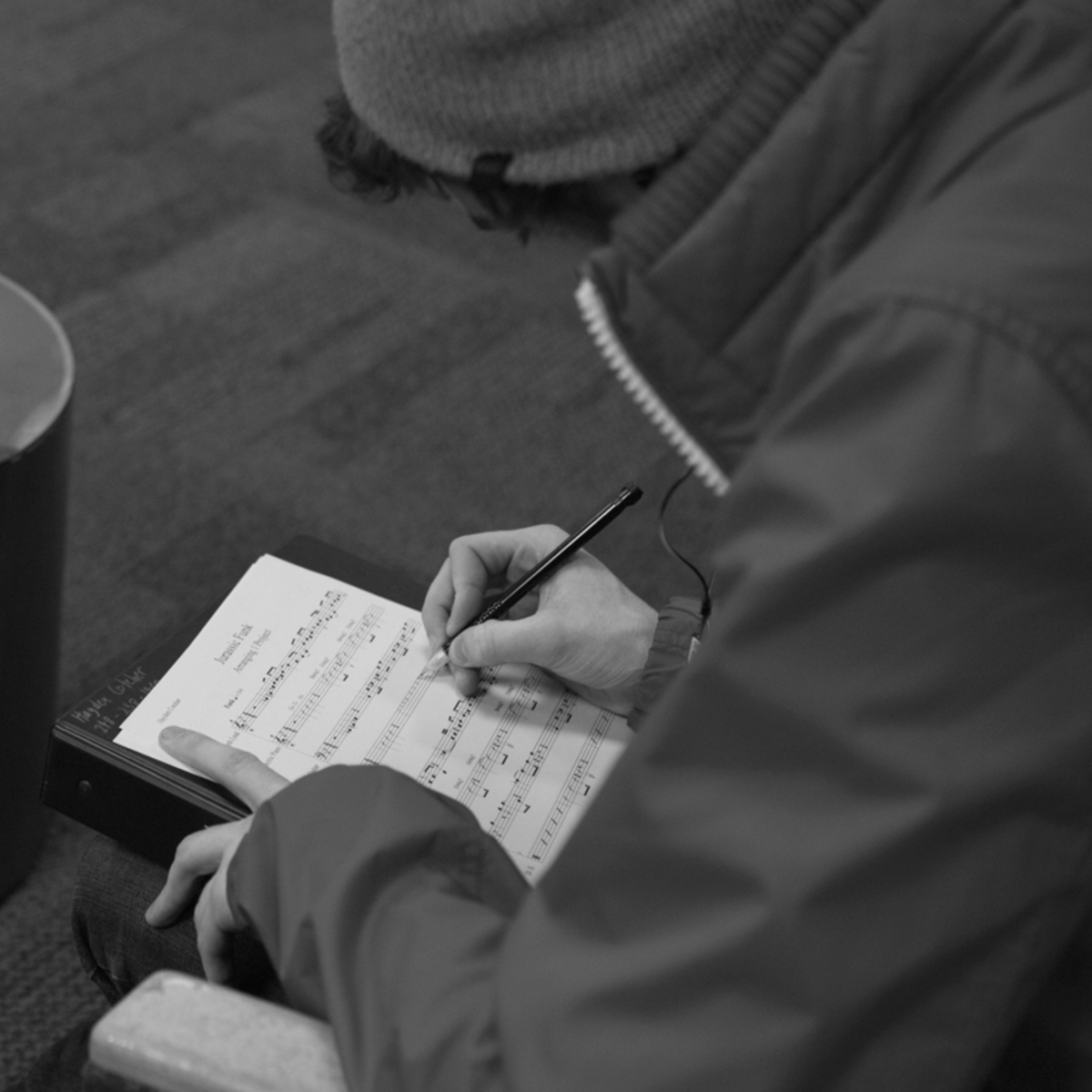

Proficiency in reading and writing standard music notation is equally vital. Arrangers must create clear, accurate scores and parts that effectively communicate their musical intentions to performers. This involves knowing the conventions of notation for various instruments and voices, including clefs, key signatures, time signatures, dynamics, and articulation markings.

Advanced theoretical knowledge, including extended harmonies, modal interchange, and contrapuntal techniques, allows for more sophisticated and creative arrangements. Continuous study and practice are essential to maintain and expand these skills.

These courses offer in-depth explorations of music theory concepts crucial for arranging.

These books provide comprehensive resources for deepening your understanding of music theory and analysis.

Instrumentation and Orchestration Techniques

Instrumentation involves choosing which instruments or voices will perform the arrangement. Orchestration is the art of assigning specific musical lines and harmonies to those instruments effectively. A good arranger understands the unique capabilities, ranges, timbres, and technical limitations of each instrument.

Effective orchestration involves balancing instrumental families, creating varied textures, and ensuring clarity of musical lines. It requires knowledge of how instruments blend together, common doubling practices, and idiomatic writing—writing music that suits the natural tendencies of an instrument.

From scoring for a string quartet to a full orchestra or a rock band with horns, the principles remain similar: use the available resources to best serve the music. Studying scores and listening critically to recordings are invaluable ways to learn these techniques.

These resources focus specifically on the techniques of orchestration and instrumentation.

Adaptability Across Genres (e.g., Classical, Pop, Film)

Versatility is a significant asset for a music arranger. While specialization is possible, the ability to work convincingly across different musical styles opens up more opportunities. Arranging a jazz standard for a pop vocalist requires different techniques than orchestrating an action sequence for a film score.

This adaptability requires familiarity with the conventions, harmonic languages, rhythmic feels, and typical instrumentation of various genres. It means understanding what makes a funk arrangement groove, how to create tension in a cinematic cue, or the nuances of vocal harmony in musical theatre.

Developing this flexibility involves broad listening, studying scores from diverse genres, and experimenting with different styles in your own arrangements. The more musical languages you understand, the more effectively you can translate music from one context to another.

Understanding different genres, like jazz, enhances an arranger's toolkit.

Tools and Technologies for Music Arrangers

Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs)

Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs) are software programs that allow for recording, editing, mixing, and producing audio. For arrangers, DAWs like Logic Pro X, Pro Tools, Ableton Live, and Cubase are essential tools. They serve as virtual studios for sketching ideas, creating mock-ups using virtual instruments, and sometimes even producing final recordings.

DAWs enable arrangers to hear their ideas realized quickly, experiment with different sounds and textures, and easily revise parts. Proficiency in at least one major DAW is standard in the industry for creating demos and collaborating with producers and composers.

Working within a DAW requires understanding MIDI sequencing, audio editing, mixing basics, and how to integrate virtual instruments and effects effectively. Many online courses offer comprehensive training on specific DAWs.

These courses provide introductions and deeper dives into popular DAWs used in music production and arrangement.

Score-Writing Software

While DAWs are great for audio mock-ups, professional score-writing software like Sibelius, Finale, or Dorico is crucial for producing the final sheet music. These programs are designed specifically for creating high-quality, publication-ready scores and individual parts.

This software offers detailed control over layout, notation symbols, text, and formatting, ensuring that the music is clear, accurate, and easy for performers to read. They often include features for part extraction, score playback using built-in or third-party sounds, and integration with DAWs.

Mastery of score-writing software streamlines the process of finalizing arrangements and delivering professional materials. Familiarity with industry standards is essential for collaboration and professional presentation.

This course focuses on MuseScore, a powerful free alternative for music notation.

Virtual Instrument Libraries

Virtual Studio Technology (VST) instruments, or virtual instruments, are software simulations of real instruments. High-quality sample libraries allow arrangers to create realistic mock-ups of their arrangements within a DAW. These libraries cover everything from orchestral instruments and pianos to synthesizers and drum kits.

Using virtual instruments effectively requires understanding MIDI programming techniques like velocity, expression, and articulation control to make the simulated instruments sound more human and expressive. They are invaluable tools for testing orchestration ideas, presenting demos to clients, and even for final production in some contexts.

Investing in and learning to use good quality sample libraries can significantly elevate the quality of an arranger's mock-ups and demos, which are often crucial for securing work.

Many orchestration and production courses touch upon using virtual instruments effectively.

Career Pathways for Music Arrangers

Typical Entry Points (e.g., Internships, Assistantships)

Breaking into the field often involves gaining practical experience and building connections. Internships with established arrangers, composers, music publishers, or production companies can provide invaluable insight and networking opportunities.

Working as an assistant to an experienced arranger or orchestrator is another common path. This might involve tasks like music copying, proofreading scores, preparing mock-ups, or handling administrative duties. While demanding, these roles offer direct mentorship and exposure to professional workflows.

Building a strong portfolio of diverse arrangements is crucial. This might involve creating arrangements for student ensembles, local bands, or personal projects. Demonstrating high-quality work is often the key to securing initial paid opportunities.

Freelance vs. Institutional Employment

Many music arrangers work on a freelance basis, taking on projects as they come. This offers flexibility and variety but requires strong self-discipline, business acumen, and networking skills to maintain a steady stream of work. Freelancers often work for artists, bands, producers, film composers, or theatre productions.

Some arrangers find employment within institutions like universities (teaching arranging), music publishing houses, production companies, or even large churches with extensive music programs. These positions may offer more stability and benefits but potentially less variety in projects.

The choice between freelance and institutional work often depends on individual preferences regarding stability, autonomy, and the type of projects desired. Some may combine part-time institutional work with freelance projects.

Revenue Streams (Commissions, Royalties)

Arrangers are typically paid through commissions or fees for their work on a specific project. The fee depends on the scope of the arrangement, the arranger's experience, the instrumentation, and the project's budget. Negotiating fair compensation is an important skill for freelancers.

In some cases, particularly for arrangements of copyrighted popular songs, arrangers might receive royalties based on sales or performances, though this is less common than upfront fees. Understanding copyright law and licensing agreements is essential, especially when arranging existing works.

Income can be variable, particularly for freelancers starting out. Diversifying skills, such as combining arranging with composing, performing, teaching, or music production, can help create a more stable financial foundation.

Understanding copyright is crucial for navigating royalties and permissions.

The career landscape for musicians, including arrangers, is influenced by broader economic factors.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, employment for music directors and composers is projected to grow slower than average, while growth for musicians and singers is projected to be about average through 2032. While arrangers aren't tracked separately, these figures suggest a competitive field requiring high skill levels.

Salary expectations can vary significantly. Resources like the Berklee Career Communities page for Arrangers can provide some general insights into potential earnings based on experience and work setting.

Formal Education in Music Arrangement

Relevant Degree Programs (e.g., Composition, Music Production)

While not always mandatory, a formal education in music can provide a strong theoretical and practical foundation. Many successful arrangers hold degrees in Music Composition, Music Theory, Jazz Studies, or Music Production.

Composition programs emphasize creating original music but heavily cover theory, orchestration, and analysis—all vital for arranging. Music Production degrees focus on recording technology and techniques, often including arranging components within the curriculum. Jazz Studies programs typically offer specific courses in jazz arranging.

Choosing a program often depends on career goals. A composition degree might suit those interested in concert or film music, while a production degree could be better for popular music genres. Look for programs with faculty who are active professional arrangers or composers.

These courses cover theoretical aspects often found in formal music degree programs.

Core Curriculum Components

A typical music degree relevant to arranging will include extensive coursework in music theory (harmony, counterpoint, form and analysis), ear training (aural skills), music history, and keyboard skills. Performance studies on a primary instrument are also standard.

Specific courses directly related to arranging might include Orchestration, Instrumentation, Jazz Arranging, Choral Arranging, or specific style analysis classes. Increasingly, curricula also incorporate music technology, including DAW proficiency and score-writing software.

Beyond coursework, ensemble participation (orchestra, band, choir, jazz ensemble) provides practical experience hearing how instruments work together and how arrangements sound in performance. Seek out programs offering hands-on arranging opportunities.

Developing aural skills is a core component of music education and essential for arrangers.

Portfolio-Building Strategies

Regardless of educational path, a strong portfolio is paramount. This collection of your best work demonstrates your skills and versatility to potential clients or employers. Formal education provides numerous opportunities to build this.

Arrange pieces for student ensembles or recitals. Collaborate with fellow students on projects. Take advantage of any opportunities for readings or performances of your arrangements by university ensembles. Seek feedback from faculty and peers.

Include diverse examples showcasing different styles, instrumentations, and skill levels. High-quality recordings (even good mock-ups) are essential alongside clean, professional-looking scores. Your portfolio is your primary calling card in the professional world.

Learning to arrange for specific contexts, like songwriting, is a great portfolio piece.

Online Learning and Skill Development

Self-Directed Learning Strategies

The internet offers vast resources for aspiring arrangers. Online courses, tutorials, score libraries, and forums provide flexible and often affordable ways to learn theory, orchestration, software skills, and genre conventions. Platforms like OpenCourser aggregate thousands of courses, making it easy to find relevant music courses.

Effective self-directed learning requires discipline and structure. Set clear goals, create a study schedule, and actively apply what you learn through practical arranging exercises. Supplement video lessons with textbook study and critical listening.

Analyze scores while listening to recordings—many classical scores are available online. Transcribe arrangements you admire to understand the techniques used. Seek feedback on your work through online communities or by connecting with mentors.

These comprehensive courses cover fundamental music theory suitable for self-study.

For foundational knowledge, these books are excellent resources.

Project-Based Skill Application

Learning theory and techniques is essential, but skills solidify through application. Create your own arranging projects: arrange a favorite song for a small combo, orchestrate a piano piece, or write a horn section part for a demo track.

Start with smaller, manageable projects and gradually increase complexity. Challenge yourself to work in different styles or with unfamiliar instruments. Use these projects to practice specific skills learned through courses or study.

Document your projects with scores and recordings (even mock-ups) to build your portfolio. Project-based learning makes study more engaging and directly contributes to career development.

These courses provide practical skills applicable to arranging projects.

Complementing Formal Education

Online learning can effectively supplement a formal music education. Use online courses to delve deeper into specific topics not covered extensively in your degree program, such as advanced orchestration techniques, specific DAWs, or niche genres.

If your program lacks certain practical elements, online resources can fill the gaps. For instance, if your university primarily uses Sibelius, you might take an online course in Finale or Dorico to broaden your software skills.

Online learning also facilitates lifelong learning after graduation. Stay updated on new technologies, trends, and techniques through ongoing online study. OpenCourser's platform helps learners manage saved courses, creating personalized learning paths that can complement any educational background.

Explore advanced theory concepts online to enhance your formal training.

Industry Trends Affecting Music Arrangers

AI-Assisted Arrangement Tools

Artificial intelligence is beginning to influence music creation, including arrangement. AI tools can generate harmonic progressions, suggest orchestrations, or even create basic arrangements automatically. This technology presents both challenges and opportunities.

While AI might automate simpler arranging tasks or assist in brainstorming, it currently lacks the nuanced musical understanding, creativity, and emotional depth of a skilled human arranger. AI is more likely to become a tool that arrangers use to enhance workflow rather than a complete replacement, especially for complex or high-stakes projects.

Arrangers may need to adapt by learning how to leverage AI tools effectively while emphasizing the unique creative value they bring. Staying informed about AI developments in music technology is becoming increasingly important.

Globalization of Music Production

Technology has made international collaboration easier than ever. Arrangers can work with composers, artists, and orchestras across the globe, sending scores and audio files digitally. This expands potential markets but also increases competition.

Understanding different cultural musical traditions can be an advantage in a globalized market. The ability to communicate effectively across potential language barriers and time zones is also beneficial.

Online platforms facilitate finding collaborators and clients worldwide. Building an online presence and leveraging digital communication tools are key aspects of navigating the global music industry.

Changing Media Formats (Streaming, Gaming)

The dominance of streaming services impacts how music is consumed and, consequently, arranged. Arrangements may need to be optimized for playback on various devices and platforms. The decline of physical media has also shifted revenue streams.

The video game industry represents a significant and growing market for music, including complex, adaptive arrangements. Arrangers skilled in creating interactive scores that respond to gameplay are in demand.

Similarly, music for television, film, and online content continues to require skilled arrangers who can adapt to different formats, genres, and production constraints. Versatility and adaptability remain key assets.

Understanding audio mastering is relevant for preparing music for different media formats.

Ethical Considerations in Music Arrangement

Copyright and Intellectual Property

Arranging existing music inherently involves copyright law. Arranging a work still under copyright typically requires permission (a license) from the copyright holder (often the publisher or composer's estate). Understanding the basics of copyright duration, public domain, and licensing is crucial.

Failure to secure proper permissions can lead to legal issues. Arrangers must be diligent in clearing rights before distributing or commercially exploiting arrangements of copyrighted material. Contracts should clearly outline rights and responsibilities regarding the arrangement.

Original elements added by the arranger might qualify for their own copyright protection as a derivative work, but this depends on the degree of originality and the terms of any licensing agreement.

This course covers essential copyright concepts relevant to the music industry.

Cultural Appropriation Concerns

When arranging music from cultures other than one's own, sensitivity and respect are paramount. Arrangers should strive to understand the cultural context and significance of the music they are working with.

Avoid superficial or stereotypical representations. Engage with the source material deeply and respectfully. When possible, collaborate with musicians from that culture or seek guidance to ensure authenticity and avoid misrepresentation.

Ethical arranging involves acknowledging sources appropriately and considering the potential impact of adapting culturally specific music for new audiences or contexts.

Crediting Practices

Proper crediting is essential in the music industry. Ensure that the original composer is clearly credited on the score and any associated materials. The arranger should also receive appropriate credit for their contribution.

Standard practice is to list the arranger's name alongside the composer's, often as "Music by [Composer] / Arranged by [Arranger]". Clear and consistent crediting acknowledges the creative contributions of all involved and maintains professional integrity.

Contracts should specify how crediting will be handled for recordings, performances, and published scores.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is formal education required to become an arranger?

While not strictly required—talent and a strong portfolio are most important—a formal education provides structured learning in theory, orchestration, and analysis, which is highly beneficial. Many successful arrangers hold music degrees. Online learning offers alternative pathways.

How competitive is the job market?

The field is competitive, requiring a high level of skill, professionalism, and networking. As noted by BLS data for related fields, growth may be limited. Success often involves building a strong reputation and finding a niche.

Can arrangers work remotely?

Yes, much arranging work can be done remotely. With DAWs, score software, and digital communication tools, collaboration across distances is common. However, some projects might require in-person attendance for rehearsals or recording sessions.

What genres offer the most opportunities?

Opportunities exist across many genres, including pop, jazz, classical, musical theatre, film/TV scoring, video games, and educational music. Versatility increases opportunities, but specialization in high-demand areas like film scoring or commercial music can also be viable.

How does AI impact career prospects?

AI is emerging as a tool that might assist or automate simpler tasks. While it could increase competition for lower-end work, skilled arrangers offering creativity, nuance, and collaboration are likely to remain in demand. Adapting to use AI tools may become beneficial.

Typical career progression timeline?

Progression varies greatly. It often starts with education/portfolio building, followed by assistant roles or small freelance projects. Building a reputation and client base takes time. Experienced arrangers may tackle larger projects, command higher fees, or move into related roles like composing or music direction.

Embarking on a career as a Music Arranger requires dedication, continuous learning, and a deep love for music. It's a path that blends technical skill with creative artistry. Whether pursuing formal education or leveraging online resources like those found on OpenCourser, building a strong foundation and a compelling portfolio is key. While challenges exist, the reward of shaping sound and bringing musical ideas to life can be immensely satisfying.