Chinese History

An Introduction to Chinese History

Chinese History encompasses the vast and intricate tapestry of human experience within the geographical region now known as China, spanning from prehistory to the present day. It is a field that examines the development of one of the world's oldest continuous civilizations, tracing the rise and fall of dynasties, the evolution of complex social structures, philosophical thought, artistic expression, and technological innovation. Understanding Chinese History involves exploring millennia of written records, archaeological discoveries, and cultural artifacts that collectively narrate a story of remarkable resilience, transformation, and profound global influence.

Delving into Chinese History can be an incredibly engaging pursuit. Imagine piecing together the strategic brilliance behind the construction of the Great Wall, a monumental feat of engineering and defense. Consider the intellectual ferment of the Hundred Schools of Thought, a period that laid the philosophical foundations for much of East Asian civilization. Or picture the bustling cosmopolitanism of Tang Dynasty Chang'an, then the largest city in the world, a vibrant hub of the Silk Road connecting East and West. These are but glimpses into the richness and dynamism that characterize the study of Chinese History, offering endless avenues for exploration and discovery.

Introduction to Chinese History

Embarking on the study of Chinese History can feel like stepping into a vast and ancient landscape. It's a journey that can be immensely rewarding, offering insights into a civilization that has profoundly shaped our world. For those new to this expansive field, a foundational understanding will illuminate the major currents and pivotal moments that define China's long past. This exploration is not just about memorizing dates and names; it's about understanding the enduring patterns, societal structures, and cultural legacies that continue to resonate today.

OpenCourser provides a wealth of resources to begin this journey. With access to thousands of online courses and books, learners can easily browse through materials on Chinese History. Features like course syllabi, summarized reviews, and the "Save to list" option help individuals find and organize resources that best suit their learning style and interests. For those looking to supplement formal education or embark on a self-directed learning path, OpenCourser offers a structured yet flexible approach to mastering this fascinating subject.

Defining the Scope and Chronological Span

Chinese History is conventionally understood to begin with prehistoric cultures like the Yangshao and Longshan, dating back thousands of years BCE, and stretches to the present day. The chronological span covers early legendary dynasties, the unification under the Qin Dynasty in 221 BCE, successive imperial eras each with unique characteristics, and the tumultuous transformations of the modern period leading to the People's Republic of China. This immense timeframe is often organized through dynastic periods, providing a framework for understanding political, social, and cultural developments.

The scope of Chinese History is equally broad, encompassing not just political and military events, but also philosophy, religion, art, literature, science, technology, and economic history. It explores the lives of emperors and peasants, scholars and soldiers, artists and merchants, providing a multifaceted view of a civilization's evolution. Regional variations within China also add layers of complexity, highlighting the diverse experiences and contributions of different peoples and areas within the vast territory. Understanding this scope helps learners appreciate the richness and depth of the subject.

For those beginning their exploration, online courses can offer structured introductions to this vast timeline. These courses often break down complex periods into digestible modules, making the long span of Chinese history more approachable. They can provide a narrative thread that connects different eras and helps learners grasp the overarching developments.

The following courses offer a strong starting point for understanding the broad sweep of Chinese history and its analytical approaches:

Highlighting Key Themes

Several key themes recur throughout Chinese History, offering lenses through which to understand its complexities. One prominent theme is the concept of the "Mandate of Heaven" (天命, Tiānmìng), which provided a justification for the rule of emperors and explained the rise and fall of dynasties—the dynastic cycle. This belief held that a just ruler maintained divine sanction, while a corrupt or ineffective one would lose it, often signaled by natural disasters or popular rebellion.

Cultural continuity and transformation is another vital theme. Despite periods of division and foreign rule, a distinct Chinese cultural identity, often rooted in Confucian principles and a shared written language, has shown remarkable persistence. Simultaneously, Chinese culture has been dynamic, absorbing and adapting influences from outside, such as Buddhism from India, and undergoing significant internal evolutions in philosophy, art, and social customs. The tension between tradition and change is a constant thread.

Geopolitical evolution also plays a crucial role. China's interactions with neighboring peoples and distant empires have shaped its borders, its political strategies, and its self-perception. From managing nomadic groups on its northern frontiers to engaging in maritime trade and diplomacy, China's relationship with the wider world has been a consistent factor in its historical development, influencing periods of expansion, isolation, and renewed global engagement. Understanding these recurring themes can provide a coherent framework for navigating the vastness of Chinese history.

To delve deeper into the philosophical and cultural underpinnings that inform these themes, consider these resources:

Mentioning Primary Sources

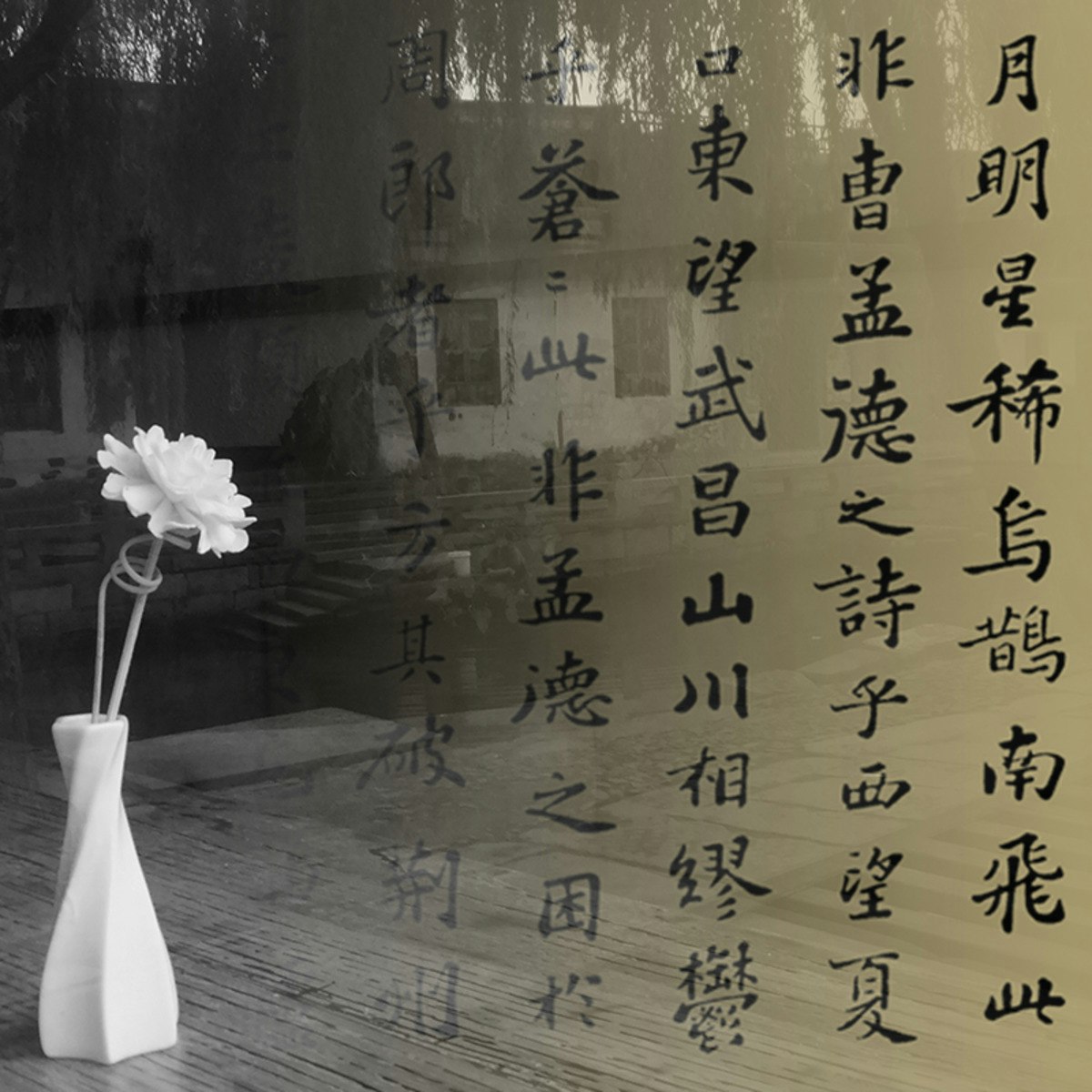

The study of Chinese History relies on a rich and diverse array of primary sources. Official dynastic histories, such as the Records of the Grand Historian (史記, Shǐjì) compiled by Sima Qian during the Han Dynasty, form a cornerstone of historical knowledge. These extensive chronicles, often commissioned by succeeding dynasties, provide detailed accounts of events, biographies of key figures, and treatises on various aspects of governance and society.

Beyond official histories, scholars draw upon a multitude of other primary materials. Archaeological findings, including oracle bones from the Shang Dynasty bearing the earliest known Chinese writing, bronze ritual vessels, ancient tombs, and remnants of cities, offer tangible connections to the past. Other important sources include philosophical texts, poetry, personal letters, diaries, legal documents, local gazetteers, and artistic creations like paintings and calligraphy. Each type of source offers unique insights and requires careful interpretation.

Access to digitized primary sources has been transformative for researchers and learners alike. Many university libraries and research institutions now offer online collections of historical texts, images, and artifacts. For instance, the Tibetan Oral History Archive Project at the Library of Congress provides valuable first-hand accounts. These digital resources allow for broader access and new methods of analysis, making it easier for students and enthusiasts to engage directly with the materials of the past.

The following course delves into one of the most foundational primary texts in Chinese historiography:

Noting the Influence of Geography

Geography has profoundly shaped the course of Chinese History. The vast and varied terrain—encompassing fertile river valleys, formidable mountain ranges, expansive deserts, and a long coastline—has influenced patterns of settlement, agriculture, communication, and defense. The Yellow River (Huang He) and the Yangtze River (Chang Jiang) valleys, in particular, served as cradles of Chinese civilization, providing water for agriculture and facilitating transportation and trade.

Natural barriers such as the Himalayan mountains to the southwest, the Gobi Desert to the north, and the Pacific Ocean to the east contributed to periods of relative isolation, allowing Chinese culture to develop with a degree of continuity. However, these barriers were not insurmountable. The northern frontiers, for example, were zones of frequent interaction and conflict with nomadic peoples, leading to the construction of fortifications like the Great Wall and influencing dynastic changes.

Regional diversity within China, fostered by geographical differences, has also been a significant factor. Variations in climate, resources, and topography led to distinct regional cultures and economies. The Qinling Mountains, for instance, traditionally divide China into northern and southern regions with different agricultural practices and cultural traits. Understanding these geographical influences is essential for appreciating the complexities of China's historical development and its internal dynamics.

Major Dynasties and Eras in Chinese History

The dynastic cycle is a fundamental concept for organizing the vast expanse of Chinese history. Each dynasty represents a distinct period, often characterized by unique political structures, social norms, cultural achievements, and territorial boundaries. Understanding these major dynasties and the transitions between them provides a chronological backbone for studying China's past. This framework allows us to trace patterns of unification, flourishing, decline, and renewal that have marked Chinese civilization for millennia.

For university students and academic researchers, a firm grasp of the dynastic periods is crucial for specialized study. It enables a deeper analysis of specific eras and the ability to compare developments across different dynasties. Online courses and academic texts often structure their content around these dynastic shifts, offering detailed explorations of each period's contributions and challenges. Exploring resources on OpenCourser can help learners identify courses that focus on specific dynasties or provide comprehensive overviews.

Shang/Zhou Foundations: Bronze Age and Mandate of Heaven

The Shang Dynasty (c. 1600-1046 BCE) is the first Chinese dynasty for which there is extensive archaeological evidence, including inscribed oracle bones and sophisticated bronze vessels. This period marked a significant development in Chinese civilization, with a complex social hierarchy, established religious practices centered on ancestor worship and divination, and a developed writing system. The mastery of bronze casting during the Shang era was unparalleled, producing ritual objects of extraordinary artistry and technical skill that were central to state power and religious ceremonies.

The succeeding Zhou Dynasty (c. 1046-256 BCE) overthrew the Shang and introduced a pivotal political and religious concept: the Mandate of Heaven (天命, Tiānmìng). This doctrine asserted that rulers were granted the right to rule by a divine power, but this mandate could be withdrawn if a ruler became unjust or incompetent, leading to their overthrow and the rise of a new dynasty. The Zhou period is further divided into the Western Zhou, characterized by a feudal-like system, and the Eastern Zhou, which saw a decline in central authority and the rise of powerful regional states during the Spring and Autumn (771-476 BCE) and Warring States (475-221 BCE) periods. This era of political fragmentation was also a time of profound intellectual and philosophical development, giving rise to Confucianism, Daoism, and Legalism.

Understanding the Shang and Zhou periods is essential as they laid the groundwork for many enduring aspects of Chinese culture, governance, and thought. The technological advancements of the Bronze Age, the establishment of foundational political ideologies, and the emergence of key philosophical schools during this long era profoundly shaped the subsequent course of Chinese history.

These courses offer insights into China's early historical and philosophical beginnings:

Qin/Han Unification: Legalism vs. Confucianism

The Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE), though short-lived, achieved the momentous feat of unifying China after centuries of division during the Warring States period. Its first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, implemented sweeping reforms based on Legalist principles, which emphasized strict laws, centralized power, and harsh punishments to maintain order. He standardized weights, measures, currency, and, crucially, the writing system, creating a foundation for a unified Chinese state and culture. The construction of massive projects like the early Great Wall and his own mausoleum with the Terracotta Army demonstrated the immense power and ambition of the Qin state.

The Han Dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE) succeeded the Qin and built upon its foundations, but adopted a more moderate approach to governance, gradually embracing Confucianism as the state ideology. Confucianism, with its emphasis on ethics, social harmony, filial piety, and education, provided a moral framework for society and government that would endure for centuries. The Han Dynasty is considered a golden age in Chinese history, marked by territorial expansion, technological advancements (such as papermaking), economic prosperity, and the flourishing of arts and culture. The Silk Road, connecting China to Central Asia and the Roman Empire, also became a major conduit for trade and cultural exchange during this period.

The interplay between Legalist efficiency and Confucian humanism during the Qin and Han periods was critical in shaping the template for imperial Chinese governance. While Legalism provided the tools for unification and state control, Confucianism offered the ideological glue that sustained the imperial system and defined Chinese social values for much of its history. The legacy of these two dynasties continues to be felt in China today.

This course provides a detailed look into this pivotal era of unification and the rise of enduring ideologies:

Tang/Song Golden Ages: Technological and Cultural Flourishing

The Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) is widely regarded as a high point in Chinese civilization, a golden age of cosmopolitanism, cultural achievement, and territorial expansion. Its capital, Chang'an (modern Xi'an), was the largest and most populous city in the world at the time, a vibrant multicultural hub that attracted traders, scholars, and religious figures from across Asia and beyond. Poetry, painting, and calligraphy flourished, with figures like Li Bai and Du Fu producing some of China's most celebrated literary works. Buddhism also reached its zenith of influence during the Tang, profoundly impacting art, philosophy, and popular religious practices.

The Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE), despite facing significant military pressures from northern nomadic empires, was a period of remarkable economic and technological advancement. Innovations such as movable type printing, gunpowder, and the compass were further developed and widely applied. Commerce thrived, with bustling cities, extensive canal networks, and the world's first paper money. Neo-Confucianism emerged as the dominant intellectual current, providing a sophisticated philosophical framework that would influence East Asia for centuries. The period also saw significant achievements in landscape painting, ceramics (especially porcelain), and a highly educated scholar-official class selected through an increasingly refined imperial examination system.

Together, the Tang and Song dynasties represent periods of extraordinary creativity, innovation, and prosperity. Their cultural and technological legacies had a lasting impact not only on China but also on the wider world, solidifying China's position as a leading civilization of its time. Many consider this combined era to be one of the peaks of Chinese historical development.

Explore the richness of these golden ages with courses that touch upon their cultural and societal transformations:

Yuan/Ming/Qing Transitions: Mongol Rule to Late Imperial Decline

The Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) marked the first time that all of China was ruled by a foreign people, the Mongols, led by Kublai Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan. The Mongols established a vast empire that stretched across Eurasia, facilitating unprecedented East-West contact, famously documented by travelers like Marco Polo. While the Yuan period saw advancements in areas like drama and mathematics, Mongol rule was also characterized by ethnic discrimination and economic policies that eventually led to widespread rebellion.

The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) overthrew the Mongols and re-established Han Chinese rule. This era is known for its impressive construction projects, including the rebuilding and expansion of the Great Wall to its present form and the construction of the Forbidden City in Beijing. Early Ming saw ambitious maritime expeditions led by Admiral Zheng He, reaching as far as East Africa. However, later Ming emperors adopted more isolationist policies. The period also saw significant growth in population, commerce, and urbanization, alongside the flourishing of arts, particularly porcelain and vernacular literature.

The Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), founded by the Manchus from the northeast, was China's last imperial dynasty. The early Qing saw territorial expansion to its greatest extent and relative stability. However, by the 19th century, the Qing faced mounting internal pressures, including population growth and social unrest, as well as external challenges from increasingly powerful Western nations seeking trade and influence. This led to events like the Opium Wars and the signing of unequal treaties, marking a period of decline and setting the stage for the end of imperial rule and the birth of modern China.

These courses examine the later imperial periods, including significant transitions and the foundations of modern China:

For a deeper dive into these pivotal dynasties, the following books offer comprehensive narratives:

Philosophical and Cultural Foundations

The philosophical and cultural foundations of China are deeply rooted in traditions that have evolved over millennia. These foundations have profoundly shaped not only social structures and governance but also artistic expression, ethical norms, and individual worldviews. Understanding these core elements is essential for anyone seeking a comprehensive grasp of Chinese history and its enduring legacy in the contemporary world. This exploration delves into the key philosophical schools, influential institutions, and the development of foundational cultural elements like the writing system.

For those in advanced studies or professional fields requiring deep cultural understanding, examining these foundations offers critical insights. The continuity and adaptation of these philosophical and cultural tenets are visible in many aspects of modern Chinese society and its global interactions. Resources available through OpenCourser's philosophy section can provide avenues for in-depth study of these influential traditions.

Confucianism's Role in Social Structure

Confucianism, originating from the teachings of Confucius (Kong Fuzi, c. 551-479 BCE), has been arguably the most influential philosophical system in shaping Chinese social structure for over two millennia. At its core, Confucianism emphasizes moral cultivation, social harmony, filial piety (respect for one's parents and elders), and the importance of well-defined social roles and hierarchies. The Five Relationships (ruler-subject, father-son, husband-wife, elder brother-younger brother, friend-friend) provided a framework for interpersonal conduct and societal order.

The emphasis on hierarchy and respect for authority became deeply ingrained in Chinese society, influencing family life, education, and governance. The family was seen as the basic unit of society, and virtues cultivated within the family, such as loyalty and respect, were expected to extend to the state. Education was highly valued as a means of moral development and for preparing individuals, particularly men, for public service. Confucian ideals permeated the legal system, social etiquette, and even artistic expression, creating a cohesive, albeit hierarchical, social fabric.

While Confucianism's dominance has been challenged at various points in Chinese history, particularly during the 20th century, its influence on social values and interpersonal relationships remains significant. Understanding its historical role is crucial for interpreting social dynamics and cultural norms in both historical and contemporary China. Many of its tenets regarding social responsibility and the importance of education continue to resonate.

These courses and topics explore the profound impact of Confucianism:

Daoist/Buddhist Influences on Art and Governance

Daoism (or Taoism), traditionally attributed to the sage Laozi, offered a complementary, and sometimes contrasting, worldview to Confucianism. Daoism emphasizes living in harmony with the Dao (the Way), the underlying natural order of the universe. It values simplicity, spontaneity, non-action (wu wei), and a deep appreciation for nature. In art, Daoist ideals inspired landscape painting that sought to capture the spirit and immensity of the natural world, often depicting humans as small figures within vast, harmonious settings. Calligraphy and poetry also drew inspiration from Daoist concepts of natural flow and effortless expression.

Buddhism, originating in India, arrived in China via the Silk Road around the 1st century CE and gradually became deeply integrated into Chinese culture. It introduced new concepts such as karma, reincarnation, and the pursuit of enlightenment. Buddhist art, including statues, murals, and temple architecture, flourished, leaving a rich visual legacy. In governance, both Daoism and Buddhism, at different times and to varying degrees, influenced rulers. Daoist ideas sometimes encouraged a more laissez-faire approach to governance, emphasizing minimal interference. Buddhism, particularly during dynasties like the Tang, enjoyed imperial patronage and played a role in state rituals and social welfare, with monasteries often providing charity and education.

The interplay between Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism created a complex spiritual and intellectual landscape in China. While Confucianism often dominated the socio-political sphere, Daoism and Buddhism profoundly shaped artistic sensibilities, personal spirituality, and provided alternative perspectives on life and governance. Their influences are often intertwined in Chinese cultural expressions.

To understand these influential philosophies and their cultural impact, consider these resources:

Imperial Examination System's Impact on Meritocracy

The imperial examination system (科舉, kējǔ) was a unique and long-lasting institution in Chinese history, serving as the primary method for recruiting government officials for over a thousand years, from its formal establishment in the Sui Dynasty (581-618 CE) until its abolition in 1905. The system was designed to select candidates based on merit, primarily their knowledge of Confucian classics, literature, and governmental affairs, rather than solely on aristocratic birth or wealth. This fostered a degree of social mobility, allowing individuals from lower socio-economic backgrounds, in theory, to rise to positions of power and influence through education and scholarly achievement.

The examinations were incredibly rigorous and highly competitive, conducted at multiple levels: local, provincial, and metropolitan (in the capital). Success brought immense prestige and the opportunity for an official career, leading to the development of a scholar-official (士大夫, shìdàfū) class that dominated China's bureaucracy and cultural life. This system reinforced the importance of Confucian values and classical education throughout society, as aspiring candidates dedicated years, often decades, to mastering the prescribed texts.

While the imperial examination system promoted a degree of meritocracy and intellectual unity, it also had limitations. It tended to favor conformity and a focus on classical scholarship over practical or scientific knowledge. Nevertheless, its impact on Chinese society was profound, shaping educational ideals, social aspirations, and the structure of government for centuries. It stands as a remarkable early attempt to institutionalize merit-based recruitment for public service.

Development of Chinese Script and Literary Traditions

The Chinese writing system is one of the oldest continuously used writing systems in the world. Its earliest confirmed forms appear on oracle bones from the late Shang Dynasty (c. 1250 BCE), used for divination. Over millennia, the script evolved through various forms, from bronze inscriptions (金文, jīnwén) and seal script (篆書, zhuànshū) to the clerical script (隸書, lìshū) of the Han Dynasty, and eventually to the standard script (楷書, kǎishū) still in use today. A key characteristic of the Chinese script is its logographic nature, where characters generally represent morphemes or words rather than individual sounds, allowing it to transcend dialectal variations and serve as a powerful unifying force throughout Chinese history.

This unique script laid the foundation for a rich and diverse literary tradition. Early classics, such as the Book of Songs (詩經, Shījīng), an anthology of poetry from the Zhou Dynasty, and the philosophical works of the Hundred Schools of Thought, established enduring literary and intellectual forms. Dynastic histories, essays, poetry (shi, ci, qu), and eventually vernacular fiction became major genres. Each era contributed distinct styles and masterpieces, from the eloquent fu rhapsodies of the Han, the regulated verse of the Tang (exemplified by poets like Li Bai and Du Fu), to the great classical novels of the Ming and Qing dynasties, such as Journey to the West and Dream of the Red Chamber.

The literary tradition was not merely an aesthetic pursuit; it was deeply intertwined with philosophy, history, and governance. Literacy and mastery of classical texts were essential for the scholar-official class and played a crucial role in cultural transmission and social cohesion. The development of printing, first woodblock and later movable type, further facilitated the dissemination of literature and knowledge, contributing to the vibrancy and continuity of Chinese literary culture.

These courses offer a glimpse into China's rich literary and linguistic heritage:

Military History and Border Relations

China's military history and its relations with bordering states and peoples are integral to understanding its long and complex past. For millennia, Chinese dynasties have contended with issues of defense, territorial integrity, and the management of diverse populations along their frontiers. These interactions have profoundly shaped China's political strategies, cultural exchanges, and its very geographical extent. This section will explore key aspects of this military and diplomatic history, from iconic defensive structures to significant conflicts and ambitious expeditions.

Understanding this domain is particularly relevant for those analyzing contemporary geopolitical dynamics and international relations, as historical precedents and strategic thinking often inform present-day policies. The challenges of border security, the impact of military technology, and the complexities of intercultural relations on the frontiers are recurring themes with enduring significance.

Great Wall Construction Strategies

The Great Wall of China (長城, Chángchéng) is not a single, continuous structure but rather a series of fortifications built, rebuilt, and maintained by various dynasties over centuries. The primary strategic purpose of these walls was to protect settled agricultural Chinese states from raids and invasions by nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples from the north and northwest, such as the Xiongnu during the Han Dynasty and later the Mongols and Manchus. Early walls were constructed by different states during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, later connected and expanded by Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of a unified China, around 221 BCE.

Construction strategies varied depending on the era, available resources, and the specific threat. Early walls were often made of rammed earth. The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), however, undertook the most extensive and sophisticated construction, using brick and stone, particularly in strategically important areas. The Ming wall system incorporated watchtowers, fortresses, and barracks, creating an integrated defense network. The placement of the wall often followed natural geographical barriers like mountain ridges to enhance its defensive capabilities.

Beyond its purely military function, the Great Wall also served as a means of border control, regulating trade and migration. While its effectiveness in completely preventing invasions was mixed—it was breached or circumvented on several occasions—the Great Wall stands as a monumental testament to the enduring strategic challenges faced by Chinese dynasties and their immense capacity for large-scale mobilization and construction.

Mongol Invasions and Silk Road Dynamics

The Mongol invasions of the 13th century, led by Genghis Khan and his successors, represent a pivotal moment in Chinese and world history. These invasions culminated in the complete conquest of China and the establishment of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) by Kublai Khan. The Mongol military machine, characterized by its skilled cavalry, discipline, and innovative tactics, overwhelmed the armies of the Jin, Southern Song, and other contemporary states. This period of conquest brought immense destruction but also led to the unification of a vast Eurasian empire under Mongol rule.

The Mongol Empire, by securing and pacifying vast swathes of Central Asia, significantly impacted the dynamics of the Silk Road. Under Mongol rule, the overland trade routes experienced a period of relative safety and increased traffic, often referred to as the "Pax Mongolica." This facilitated greater commercial and cultural exchange between East and West. Merchants, missionaries, and travelers like Marco Polo journeyed across the continent, leading to a greater European awareness of Chinese goods, technologies, and culture. Conversely, influences from the West also reached China during this time.

While Mongol rule in China (the Yuan Dynasty) was relatively short-lived, its impact was profound. It altered the political landscape, introduced new cultural elements, and reshaped patterns of trade and interaction across Eurasia. The legacy of the Mongol invasions and their effect on the Silk Road underscore the interconnectedness of different regions and the far-reaching consequences of military and political transformations.

This book offers a broader context of Chinese civilization which includes these periods of interaction and conflict:

Maritime Expeditions (Zheng He)

In the early 15th century, during the Ming Dynasty, China embarked on a series of extraordinary maritime expeditions led by the eunuch admiral Zheng He. Between 1405 and 1433, Zheng He commanded seven epic voyages with enormous fleets, some consisting of hundreds of ships and tens of thousands of men, including massive "treasure ships" (寶船, bǎochuán) that were far larger than contemporary European vessels. These expeditions sailed across the Indian Ocean, reaching Southeast Asia, India, the Persian Gulf, Arabia, and the eastern coast of Africa.

The primary purposes of Zheng He's voyages were diplomatic and political, aimed at establishing Chinese prestige, projecting Ming power, and enrolling foreign states into the Chinese tributary system. The fleets carried valuable Chinese goods like silk and porcelain for trade and gifts, and brought back exotic items, animals (such as giraffes), and envoys from numerous kingdoms. These voyages demonstrated China's advanced shipbuilding technology and navigational skills at the time.

However, these grand maritime expeditions were abruptly halted after 1433 due to a combination of factors, including changes in imperial policy, the immense cost, and a renewed focus on northern land-based threats. This decision marked a turning point, as China gradually withdrew from extensive state-sponsored overseas exploration just as European powers were beginning their age of discovery. Zheng He's voyages remain a remarkable chapter in global maritime history, highlighting a period when China possessed an unparalleled naval capacity.

19th-Century Conflicts with Western Powers

The 19th century was a period of profound crisis and transformation for China, marked by a series of debilitating conflicts with Western powers. These encounters, often driven by Western imperial ambitions and trade interests, exposed China's military and technological weaknesses and led to a significant erosion of its sovereignty. The First Opium War (1839-1842) erupted over Britain's illegal opium trade into China and China's attempts to suppress it. British military superiority resulted in a decisive Chinese defeat and the signing of the Treaty of Nanking, the first of many "unequal treaties." This treaty ceded Hong Kong to Britain, opened several treaty ports to foreign trade, and imposed a large indemnity on China.

The Second Opium War (1856-1860), involving Britain and France, further weakened the Qing Dynasty. It led to the looting and burning of the Old Summer Palace in Beijing and more concessions, including the legalization of the opium trade and the opening of more ports. Subsequent decades saw further foreign encroachments, including the Sino-French War (1884-1885) and the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), the latter resulting in a humiliating defeat and the loss of Taiwan. These conflicts, collectively referred to by some in China as the "Century of Humiliation," fueled anti-foreign sentiment and contributed to internal unrest, such as the Taiping Rebellion and the Boxer Uprising.

These 19th-century conflicts had a devastating impact on the Qing Dynasty, undermining its authority and forcing China to confront the challenges of modernization in a world increasingly dominated by Western powers. They set the stage for the revolutionary movements of the early 20th century that would ultimately lead to the end of imperial rule. The legacy of these events continues to shape China's perception of its modern history and its relationship with the wider world.

The following book touches upon the complexities of this era within the broader sweep of Chinese history:

Technological Contributions of Chinese History

Throughout its long history, China has been a center of significant technological innovation, with many inventions and discoveries that have had a profound impact both domestically and globally. From foundational agricultural techniques to groundbreaking inventions that reshaped the world, Chinese ingenuity has a rich legacy. Understanding these contributions is essential not only for appreciating China's historical role in scientific and technological development but also for contextualizing its modern technological ambitions.

Academic researchers and industry practitioners alike can benefit from exploring this history. It reveals patterns of innovation, the societal conditions that fostered or hindered scientific progress, and the complex processes of technological diffusion. For those interested in the history of science and technology, China offers a compelling and deeply rewarding field of study. You can explore related courses on OpenCourser's technology section for broader context.

Four Great Inventions: Paper, Printing, Gunpowder, Compass

The "Four Great Inventions" (四大發明, Sì Dà Fāmíng) of ancient China are celebrated for their historical significance and transformative impact on world civilization. These are papermaking, printing (both woodblock and movable type), gunpowder, and the compass. While other Chinese inventions were also highly significant, these four are particularly noted for their role in the development of human society globally.

Papermaking is traditionally attributed to Cai Lun in the Han Dynasty (around 105 CE), although earlier forms of paper existed. This invention provided an affordable and convenient writing medium, revolutionizing record-keeping, communication, and the spread of knowledge. Printing technology, initially developed as woodblock printing during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) and later as movable type printing by Bi Sheng in the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE), enabled the mass production of texts, greatly facilitating education and the dissemination of ideas.

Gunpowder was discovered by Daoist alchemists searching for an elixir of immortality, likely during the Tang Dynasty. Initially used for fireworks, its military applications were developed over time, leading to the creation of various firearms and explosive devices that transformed warfare. The magnetic compass, also originating in China, likely during the Han Dynasty and initially used for divination, was later adapted for navigation during the Song Dynasty, revolutionizing maritime travel and exploration. The transmission of these Four Great Inventions to other parts of the world, particularly Europe during the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, played a crucial role in global historical developments.

These courses touch upon the cultural and societal contexts in which such innovations occurred:

Agricultural Innovations: Iron Plows, Crop Rotation

Agriculture has always been the backbone of the Chinese economy and society, and numerous innovations throughout history allowed for increased food production to support a growing population. The development and widespread use of iron plows, beginning in the Warring States period and becoming common during the Han Dynasty, significantly improved farming efficiency. Iron plows were stronger and more durable than earlier wooden or bronze implements, allowing for deeper tilling and the cultivation of harder soils.

Chinese farmers also developed sophisticated techniques for crop rotation and soil conservation. Understanding the importance of maintaining soil fertility, they practiced methods such as intercropping and planting nitrogen-fixing crops like soybeans. The development of new, faster-ripening, and drought-resistant strains of rice, particularly Champa rice introduced from Southeast Asia during the Song Dynasty, allowed for multiple harvests per year in southern China and the expansion of rice cultivation into new areas.

Other agricultural innovations included the invention of the seed drill, which allowed for more precise planting of seeds, and various irrigation and water-control systems. These advancements, accumulated over centuries, enabled China to sustain one of the world's largest populations and contributed to periods of economic prosperity and social stability. The ingenuity displayed in agriculture underscores the practical and empirical nature of much of Chinese scientific and technological development.

Hydraulic Engineering Projects

Given the importance of rivers for agriculture, transportation, and flood control, hydraulic engineering has a long and distinguished history in China. The management of major rivers like the Yellow River, often prone to devastating floods (earning it the name "China's Sorrow"), and the Yangtze River necessitated large-scale water control projects from very early times. These projects required sophisticated planning, organization of labor, and engineering skill.

One of the most remarkable early examples is the Dujiangyan Irrigation System in Sichuan province, constructed during the Qin Dynasty in the 3rd century BCE. This ingenious system diverts water from the Min River for irrigation while also mitigating floodwaters, and it continues to function to this day, a testament to its brilliant design. Other major hydraulic projects included the construction of extensive canal systems for irrigation and transportation.

The Grand Canal, the world's longest artificial waterway, is perhaps the most famous example. Begun in earlier periods and significantly expanded during the Sui Dynasty (581-618 CE) and later dynasties, it linked the Yellow River and Yangtze River basins, facilitating the transport of grain and other goods between northern and southern China. These monumental hydraulic engineering feats demonstrate the advanced capabilities of Chinese states in resource management and large-scale public works, which were crucial for economic integration and political stability.

Traditional Medicine Developments

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) is a comprehensive medical system with a history spanning several thousand years. Its theoretical foundations are rooted in ancient Chinese philosophy, including concepts like Yin and Yang, the Five Elements (Wuxing), and Qi (vital energy). TCM emphasizes a holistic approach to health, viewing the human body as an interconnected system where balance and harmony are essential for well-being. Diagnosis often involves observing symptoms, checking the pulse, and examining the tongue.

Key therapeutic modalities in TCM include acupuncture (the insertion of fine needles at specific points on the body), moxibustion (the burning of mugwort near the skin), herbal medicine (utilizing a vast pharmacopoeia of plant, animal, and mineral substances), Tui Na (therapeutic massage), and dietary therapy. Over centuries, a vast body of medical literature was compiled, including classic texts like the Huangdi Neijing (Yellow Emperor's Inner Canon) and the Shanghan Lun (Treatise on Cold Damage Disorders).

Developments in TCM included the refinement of diagnostic techniques, the classification of diseases, the systematic compilation of herbal remedies, and the mapping of acupuncture meridians. While distinct from Western medicine, TCM has developed sophisticated theories and practices that continue to be used by millions worldwide and are an area of ongoing research and integration. Its long history reflects a continuous tradition of observation, practice, and theoretical development in healthcare.

These courses provide an introduction to aspects of traditional Chinese medicine and its historical context:

Formal Education Pathways

For individuals aspiring to specialize in Chinese History, formal education provides a structured and rigorous path to developing deep expertise. This journey typically involves progressing through undergraduate and graduate programs, engaging with primary sources and scholarly debates, and potentially contributing to the field through original research. Academic institutions worldwide offer specialized programs that equip students with the necessary linguistic skills, historiographical knowledge, and research methodologies.

Navigating these pathways requires dedication and a clear understanding of the academic landscape. University students considering this specialization should be prepared for a demanding but intellectually stimulating course of study. OpenCourser can be a valuable tool in this process, helping students explore introductory courses, identify potential areas of interest, and supplement their formal education with additional learning resources. The OpenCourser Learner's Guide offers tips on how to create a structured curriculum and make the most of online learning opportunities.

Undergraduate Programs: Language Requirements and Core Curricula

Undergraduate programs in Chinese History, or History programs with a specialization in China, typically aim to provide students with a broad understanding of the chronological sweep of Chinese history, key themes, and major historiographical debates. Core curricula often include survey courses covering ancient, imperial, and modern China, as well as thematic courses on topics such as Chinese philosophy, art, society, or foreign relations.

A significant component of many undergraduate programs focusing on Chinese History is language study. Proficiency in Modern Standard Chinese (Mandarin) is often required or strongly recommended, as it allows students to access a wider range of primary and secondary sources and engage more deeply with the culture. Some programs may also introduce Classical Chinese, which is essential for reading pre-modern texts. Students should expect to dedicate considerable time to language acquisition alongside their historical studies.

Beyond coursework, undergraduate programs may encourage or require a senior thesis or research project, providing students with an opportunity to engage in independent scholarly inquiry under the guidance of a faculty mentor. Internships at museums, archives, or cultural organizations, as well as study abroad programs in China or Taiwan, can also offer invaluable experiential learning opportunities. Successfully completing an undergraduate program in this field provides a strong foundation for graduate study or careers requiring expertise in Chinese history and culture.

Many universities with strong East Asian Studies departments offer excellent programs. For example, institutions like Harvard University and UC Berkeley have renowned programs that students might explore. Prospective students should research specific university offerings to find programs that align with their interests.

These courses, often part of university offerings, provide a taste of undergraduate-level study:

Graduate Research: Paleography and Archival Studies

Graduate research in Chinese History, typically at the Master's (MA) and Doctoral (PhD) levels, involves highly specialized and intensive study. Students focus on specific periods, themes, or methodologies, and are expected to produce original scholarly work, culminating in a substantial thesis or dissertation. A core component of graduate training is the development of advanced research skills, including the ability to work with primary sources in their original languages.

For historians of pre-modern China, paleography—the study of ancient and historical handwriting—is often crucial. This involves deciphering and interpreting texts written in various forms of classical Chinese script found on materials such as oracle bones, bronze vessels, bamboo slips, silk manuscripts, and early paper documents. Archival studies are equally important, particularly for modern Chinese history, requiring researchers to navigate and analyze vast collections of government documents, personal papers, institutional records, and other unpublished materials held in archives in China and around the world.

Graduate programs emphasize critical engagement with existing scholarship, theoretical frameworks, and historiographical debates. Students learn to formulate research questions, develop methodologies, and present their findings in academic settings. Proficiency in multiple languages, including Modern and Classical Chinese, and often Japanese or other relevant languages, is usually essential. The goal of graduate research is to contribute new knowledge and interpretations to the field of Chinese History.

Aspiring graduate students should seek programs with faculty whose research interests align with their own. For example, institutions like Cambridge University and Oxford University have strong traditions in sinology and Chinese historical research.

Fieldwork Opportunities: Archaeological Digs

For certain specializations within Chinese History, particularly those focused on early periods or material culture, fieldwork can be an integral part of the research process. Archaeological digs in China offer unparalleled opportunities to uncover new evidence about ancient civilizations, settlement patterns, burial practices, and daily life. These excavations can yield artifacts, structural remains, and other material traces that provide direct insights into the past, often complementing or challenging textual sources.

Participating in archaeological fieldwork typically requires specialized training in excavation techniques, artifact identification, and site recording. It often involves collaboration between Chinese and international archaeological teams and adherence to strict protocols for excavation and preservation. For historians, involvement in such projects can provide a deeper understanding of the material context of the periods they study and allow them to engage directly with primary evidence as it is unearthed.

While opportunities for international scholars to lead or independently conduct large-scale excavations in China may be limited, collaborative projects and participation in field schools or as team members can provide invaluable experience. Fieldwork is not limited to archaeology; historians may also conduct fieldwork by visiting historical sites, interviewing local communities (for more contemporary history), or examining local archives and collections. Such experiential research can enrich historical understanding and lead to new perspectives.

Institutional Partnerships with Chinese Universities

Many universities and research institutions outside of China have established partnerships with Chinese universities. These collaborations can take various forms, including joint research projects, faculty and student exchange programs, dual-degree programs, and shared academic conferences and workshops. Such partnerships are highly valuable for scholars and students of Chinese History, providing direct access to resources, academic communities, and cultural immersion in China.

For students, exchange programs offer the chance to study at a Chinese university, improve language skills, take courses from Chinese professors, and experience the culture firsthand. This can be particularly beneficial for dissertation research, allowing access to archives, libraries, and fieldwork sites. For faculty, these partnerships facilitate collaborative research with Chinese colleagues, access to unique scholarly materials, and opportunities to share their own work with an international audience.

These institutional links foster a global network of scholarship in Chinese History, promoting cross-cultural understanding and the exchange of diverse perspectives. They play a vital role in advancing the field by enabling deeper engagement with China's rich historical heritage and its contemporary academic landscape. Prospective students and researchers should investigate the international partnerships of institutions they are considering, as these can significantly enhance their educational and research opportunities.

Courses offered by Chinese universities on international platforms are one example of such global academic engagement:

Digital Resources and Self-Directed Learning

The digital age has revolutionized how we learn about and engage with history, and Chinese History is no exception. A vast array of online resources now makes it possible for career pivoters, curious learners, and even seasoned academics to explore China's rich past from anywhere in the world. This accessibility opens up exciting avenues for self-directed learning, allowing individuals to tailor their studies to their specific interests and pace. Whether you're looking to build a foundational understanding or delve into niche topics, the digital realm offers a wealth of opportunities.

For those embarking on a self-directed learning journey, platforms like OpenCourser can be invaluable. You can search for specific courses on Chinese History, compare different offerings, and read reviews to find the best fit. Furthermore, OpenCourser's "Save to list" feature allows learners to curate their own learning paths by organizing courses and books, making the process of self-study more structured and manageable.

Digitized Primary Sources and Translation Tools

One of the most significant impacts of digitization on historical research is the increased accessibility of primary sources. Numerous libraries, archives, and institutions worldwide have undertaken projects to digitize historical Chinese texts, manuscripts, maps, photographs, and artifacts. This means that rare and fragile documents, once only accessible to a few scholars with the means to travel to specific collections, can now be viewed online by a global audience. Websites like the Chinese Text Project offer vast collections of pre-modern Chinese texts, often with search functionalities and linked dictionaries.

For those who are not yet proficient in Classical or Modern Chinese, online translation tools and digitized bilingual editions can be helpful starting points. While machine translation should be used with caution for academic purposes, it can provide a preliminary understanding of a text's content. More importantly, many digitized collections include scholarly translations or provide tools that assist with character recognition and dictionary lookups, significantly lowering the barrier to engaging with original materials. The International Dunhuang Project, for example, provides access to manuscripts from Dunhuang with images, transcriptions, and often translations.

These digital resources empower self-directed learners to go beyond secondary interpretations and engage directly with the voices and materials of the past. This can lead to a richer, more nuanced understanding of Chinese history and allows for independent exploration and discovery. The availability of such resources encourages a more active and critical approach to learning.

This book provides an excellent overview and can guide learners to key historical periods often covered by primary sources:

Virtual Museum Collections

Museums around the world house extensive collections of Chinese art and artifacts, and many now offer virtual tours or online access to their collections. These digital platforms allow individuals to explore exquisite ceramics, bronzes, paintings, calligraphy, textiles, and other cultural treasures from different periods of Chinese history without leaving their homes. High-resolution images, often with detailed descriptions and curatorial notes, provide rich contextual information.

Virtual museum collections can be an engaging way to learn about the material culture, artistic traditions, and daily life of past Chinese societies. For example, the websites of institutions like the National Palace Museum in Taipei or the British Museum offer extensive online galleries of their Chinese holdings. Exploring these collections can complement textual learning by providing a visual and tangible connection to the past.

For self-directed learners, virtual museums offer a flexible and immersive learning experience. One can focus on specific types of objects, artistic styles, or historical periods. Some museums also provide educational resources, online lectures, and interactive exhibits related to their Chinese collections, further enhancing the learning opportunities. This direct engagement with artifacts, even virtually, can spark curiosity and deepen one's appreciation for the richness and diversity of Chinese cultural heritage.

These courses can help contextualize the artifacts and cultural periods one might encounter in museum collections:

Historical GIS Mapping Projects

Historical Geographic Information Systems (GIS) are powerful tools that allow researchers and learners to explore the spatial dimensions of history. Several projects focused on Chinese history utilize GIS to map historical administrative boundaries, trade routes, settlement patterns, environmental changes, and the locations of significant events or sites. These interactive maps can provide new perspectives on historical developments by visualizing them geographically.

Projects like the China Historical GIS (CHGIS) at Harvard University provide datasets and tools for mapping Chinese history from the imperial period to the 20th century. By overlaying different types of historical and geographical data, users can analyze spatial relationships and patterns that might not be apparent from textual sources alone. For example, one could map the spread of a particular rebellion, the extent of a canal system, or the distribution of different ethnic groups over time.

For self-directed learners, engaging with historical GIS projects can make history more dynamic and tangible. It allows for an exploratory approach, where one can ask spatial questions and seek answers through interactive mapping. While creating one's own historical GIS maps requires specialized skills, many projects offer user-friendly online interfaces that allow anyone to explore pre-existing maps and data. This adds a valuable geographical layer to the study of Chinese history.

Independent Research Project Ideas

Self-directed learning in Chinese History can be greatly enhanced by undertaking independent research projects. These projects allow learners to delve deeply into topics of personal interest, develop research skills, and synthesize information from various sources. The vastness of Chinese history offers countless possibilities for such projects, catering to a wide range of interests and skill levels.

For example, a learner might choose to research the life of a particular historical figure, the development of a specific art form (like porcelain or landscape painting), the history of a particular city, the impact of a specific technological innovation, or the details of a significant event or period. The project could involve reading scholarly articles and books, exploring digitized primary sources, virtually visiting museum collections, and perhaps even learning some basic Chinese characters related to the topic.

The output of an independent research project could take various forms, such as a written essay, a presentation, a website, a blog series, or even a creative work inspired by historical events. The process of researching and creating such a project can be highly rewarding, fostering critical thinking, analytical skills, and a deeper, more personal connection to the subject matter. OpenCourser's resources, including its vast catalog of courses and books, can provide excellent starting points and foundational knowledge for such independent explorations. For those looking for structured learning, OpenCourser's deals page might offer affordable courses to support their research.

To gather foundational knowledge for such projects, consider these comprehensive courses:

A broad historical understanding is often key, which these books can provide:

Chinese History in Global Markets

A nuanced understanding of Chinese history is increasingly valuable in the context of global markets. Historical patterns of trade, cultural exchange, and geopolitical thinking often provide essential context for contemporary economic trends, business practices, and international relations involving China. Professionals in fields such as finance, international business, diplomacy, and marketing can leverage historical knowledge to make more informed decisions, navigate cultural complexities, and anticipate future developments.

For financial analysts and international relations professionals, insights from Chinese history can illuminate long-term strategic thinking, the cultural underpinnings of economic policy, and the historical roots of current global initiatives. This understanding moves beyond surface-level analysis, offering a deeper appreciation of the forces that shape China's engagement with the world. Exploring resources like those found in OpenCourser's business category can complement historical knowledge with practical business insights.

Historical Basis for Belt and Road Initiative

China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a massive global infrastructure development strategy, has significant historical parallels, most notably with the ancient Silk Road. The Silk Road was not a single route but a vast network of overland and maritime pathways that connected China with Central Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Europe for centuries, facilitating trade in goods like silk, tea, and porcelain, as well as the exchange of ideas, technologies, and cultures. Understanding the historical significance of the Silk Road—its economic impact, its role in cultural diffusion, and the geopolitical dynamics that shaped it—provides a valuable framework for analyzing the ambitions and potential implications of the BRI.

The BRI explicitly evokes the legacy of the historical Silk Road, aiming to enhance connectivity and cooperation across continents. By studying the successes and failures of past efforts to manage long-distance trade and infrastructure networks, analysts can gain insights into the challenges and opportunities facing the BRI. Historical knowledge of China's tributary system, its past infrastructure projects (like the Grand Canal), and its historical foreign relations can also inform assessments of the BRI's strategic goals and its reception in participating countries. According to some analyses, such as discussions on Council on Foreign Relations, understanding these historical underpinnings is crucial for a comprehensive view of this contemporary initiative.

A historical perspective helps to contextualize the scale of the BRI, its emphasis on infrastructure, and its potential to reshape global trade patterns and geopolitical alignments. It encourages a look beyond immediate economic figures to consider the longer-term historical currents that may be at play.

This course touches upon modern China's global interactions, which are often viewed through historical lenses:

Tea/Silk Trade Patterns and Modern Commerce

The historical trade in iconic Chinese goods like tea and silk offers valuable lessons for understanding modern commerce and China's role in global markets. For centuries, silk was one of China's most prized exports, so much so that the primary Eurasian trade routes became known as the Silk Road. The production techniques for silk were a closely guarded secret for a long time, giving China a virtual monopoly and making silk a symbol of luxury and status in places like the Roman Empire. Similarly, tea, originating in China, became a globally consumed beverage, with its trade profoundly impacting economies and even international relations, as seen in events like the Boston Tea Party.

Studying the historical patterns of this trade—how routes were established, how commercial relationships were managed, the role of state control versus private enterprise, and how demand fluctuated—can provide insights into enduring aspects of international commerce. Issues such as quality control, branding (even in nascent forms), supply chain management, and the impact of changing consumer preferences were relevant then as they are now. The historical tea and silk trades also highlight the economic power that can accrue from unique products and specialized knowledge.

Today, as China is a global manufacturing hub and a major player in international trade, understanding these historical precedents can be illuminating. The legacy of these ancient trade networks and the cultural significance of these products continue to influence modern Chinese business identity and its approach to global commerce. Knowledge of these historical trade dynamics can help businesses better understand market development, branding, and the cultural dimensions of trade with China.

Cultural Heritage in Brand Marketing

Chinese cultural heritage, with its rich history, symbolism, and aesthetic traditions, is increasingly being leveraged in brand marketing, both by domestic Chinese companies and international brands seeking to connect with Chinese consumers. Elements such as traditional calligraphy, auspicious symbols (like dragons or phoenixes), references to historical figures or legends, traditional color palettes (like red and gold), and motifs from classical art and literature are often incorporated into product design, advertising campaigns, and brand storytelling.

An understanding of Chinese history and cultural nuances is crucial for effectively and respectfully utilizing these elements. Misinterpretations or superficial applications of cultural symbols can lead to negative perceptions or even offense. Conversely, brands that demonstrate a genuine appreciation and understanding of Chinese heritage can build stronger emotional connections with consumers and differentiate themselves in a competitive market. This often involves more than just aesthetics; it means understanding the values, beliefs, and historical narratives associated with particular cultural elements.

For marketing professionals, knowledge of Chinese history can provide a deep well of inspiration for creating culturally resonant campaigns. It can inform the choice of imagery, messaging, and even the timing of marketing initiatives to align with important cultural festivals or historical commemorations. As Chinese consumers increasingly value authenticity and cultural pride, brands that can thoughtfully integrate historical and cultural heritage into their identity are likely to find greater success.

Courses that explore Chinese culture and arts can provide foundational knowledge for understanding these marketing dynamics:

Historical Analogies in Economic Policymaking

Historical analogies and precedents often play a role, explicitly or implicitly, in economic policymaking in China. Policymakers and strategists may draw upon lessons from China's long economic history—its periods of prosperity and decline, its experiences with state monopolies, land reform, currency systems, and foreign trade—to inform current decisions. For example, historical experiences with managing large-scale infrastructure projects, controlling inflation, or fostering regional development might be referenced in contemporary discussions.

Understanding these historical reference points can be crucial for analysts seeking to interpret China's economic policies and predict future trends. Phrases or concepts rooted in historical events or philosophies (e.g., references to the "well-field system" or periods of "harmonious society") can carry significant weight and convey deeper meanings to a domestic audience. An awareness of how history is understood and utilized in policy discourse can provide valuable context that might be missed by purely economic or political analyses. Research from institutions like the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) sometimes delves into the historical context of economic developments.

For professionals in global markets, recognizing these historical undercurrents can lead to a more nuanced understanding of China's economic trajectory and policy priorities. It encourages looking beyond immediate data points to consider the long-term historical consciousness that may shape economic thinking and strategic planning. This historical literacy can be a significant asset in navigating the complexities of China's economic landscape.

These courses provide insights into contemporary China, where historical understanding often informs present-day decisions:

A comprehensive understanding of modern Chinese history is also beneficial, as provided by this book:

Ethical Considerations in Historical Interpretation

The study and interpretation of Chinese history, like all historical inquiry, involve significant ethical considerations. Historians grapple with questions of objectivity, the treatment of sensitive or controversial topics, the responsible use of sources, and the impact of their narratives on contemporary understanding and identity. These challenges are particularly acute in a field as vast, complex, and politically relevant as Chinese history. Engaging with these ethical dimensions is crucial for academic researchers, PhD candidates, and anyone seeking a nuanced understanding of the past.

Navigating these issues requires a commitment to rigorous methodology, intellectual honesty, and an awareness of the potential biases and perspectives that can influence historical interpretation. The ongoing dialogue within the historical profession about these ethical challenges is vital for maintaining the integrity and relevance of historical scholarship.

Nationalism vs. Historical Objectivity

One of the central ethical challenges in interpreting Chinese history is navigating the tension between nationalist narratives and the pursuit of historical objectivity. Nationalist interpretations often seek to present a heroic, unified, and often unblemished view of the nation's past, emphasizing achievements and downplaying or reinterpreting problematic episodes. While national pride can be a powerful force for social cohesion, it can also lead to the politicization of history, where historical accounts are shaped to serve contemporary political agendas rather than to accurately reflect the complexities and ambiguities of the past.

Historians striving for objectivity aim to base their interpretations on a critical evaluation of all available evidence, to acknowledge different perspectives, and to avoid anachronism or presentism (judging the past by present-day values). This involves being transparent about one's own potential biases and engaging with a wide range of sources, including those that may challenge prevailing narratives. The ethical imperative for historians is to resist pressures to conform to officially sanctioned or popularly accepted versions of history if the evidence suggests a different or more nuanced understanding.

This tension is not unique to Chinese history but is particularly pronounced given China's long and often contested past, as well as the significant role that history plays in shaping national identity and political legitimacy. Balancing a respectful understanding of national narratives with a critical and evidence-based approach is an ongoing ethical task for scholars in the field.

Treatment of Sensitive Topics (e.g., Cultural Revolution)

Chinese history contains numerous periods and events that are considered sensitive or controversial, such as the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution, the 1989 Tiananmen Square events, and issues related to ethnic minorities or territorial disputes. The ethical treatment of these topics requires careful handling, a commitment to truth-telling, and an awareness of the potential impact on individuals and communities who were directly affected or whose memories are deeply intertwined with these events.

Historians face ethical dilemmas regarding access to sources (which may be restricted for sensitive topics), the interpretation of conflicting accounts, and the potential risks to individuals who provide information. There is an ethical responsibility to approach these subjects with empathy and respect for human suffering, while also maintaining scholarly rigor and avoiding hagiography or demonization. The goal is to understand these complex events in their historical context, exploring their causes, consequences, and the diverse human experiences associated with them.

For PhD candidates and academic researchers, tackling sensitive topics often requires courage, meticulous research, and a nuanced approach. It also involves navigating the political and social sensitivities that may surround such research, both within China and internationally. The ethical commitment is to contribute to a more complete and accurate understanding of the past, even when it is painful or challenging. Books like "Mao's Great Famine" and "The Cultural Revolution" by Frank Dikötter, or "Mao" by Jon Halliday or Philip Short, delve into such sensitive periods and are important for understanding these debates.

Archaeological Ethics and Relic Preservation

Archaeology plays a vital role in uncovering and understanding China's ancient past, but it also comes with significant ethical responsibilities regarding the excavation, interpretation, preservation, and ownership of cultural relics. Ethical archaeological practice involves minimizing damage to sites, ensuring meticulous recording and documentation, and collaborating with local communities and authorities. The preservation of unearthed artifacts and sites for future generations is a paramount concern, often involving complex conservation challenges.

Issues of cultural heritage ownership and repatriation can also be ethically fraught, particularly concerning artifacts that may have been removed from China during periods of conflict or colonial exploitation. There are ongoing international debates about the rightful custodianship of such relics. Furthermore, the commercialization of archaeological finds and the problem of looting and illicit trafficking in antiquities pose serious ethical and legal challenges that require constant vigilance and international cooperation.

For historians and archaeologists working with Chinese material culture, ethical considerations include respecting the cultural significance of objects and sites, ensuring that research benefits and is shared with the source communities where appropriate, and advocating for responsible stewardship of China's rich archaeological heritage. This includes careful consideration of how human remains are treated and studied. An example of a resource that touches on the importance of relics is the course below, which highlights their cultural value.

Cross-Cultural Comparative Methodologies

When studying Chinese history, particularly in a global context, scholars often employ cross-cultural comparative methodologies. This involves comparing aspects of Chinese history (such as political systems, philosophical ideas, social structures, or technological developments) with those of other civilizations. While comparative approaches can yield valuable insights and help to highlight unique features or universal patterns, they also present ethical challenges.

One key ethical consideration is the avoidance of Eurocentrism or other forms of cultural bias, where one civilization is implicitly or explicitly treated as the norm or standard against which others are measured. It is important to understand each culture or historical context on its own terms before making comparisons. Oversimplification or the imposition of anachronistic or inappropriate analytical categories can lead to distorted understandings. A responsible comparative methodology requires deep knowledge of all cultures being compared, sensitivity to context, and a clear articulation of the basis and purpose of the comparison.

Furthermore, scholars must be mindful of how comparisons might be used or interpreted, particularly in contexts where historical narratives are politically charged. The goal of comparative history should be to foster deeper understanding and mutual respect, rather than to rank civilizations or reinforce stereotypes. Ethical cross-cultural comparison encourages a nuanced appreciation of human diversity and the complex ways in which societies have developed across time and space.

This course explores a unique cross-cultural historical interaction:

And this book explores Western perceptions of China, relevant to cross-cultural understanding:

Frequently Asked Questions (Career Focus)

Embarking on a path of study in Chinese History can be deeply rewarding, but it's natural to have questions about how this knowledge translates into career opportunities. This section addresses common inquiries from individuals considering how expertise in Chinese History can be applied in professional settings, the skills it cultivates, and the types of roles available. Whether you're a student, a career pivoter, or simply curious, these insights aim to provide practical guidance.

Understanding the career landscape is an important step in planning your educational and professional journey. While a direct "historian" role is one path, the skills gained from studying Chinese History are often transferable to a wide range of fields. If you are exploring career options, the Career Development section on OpenCourser might offer additional resources and insights into various professional paths.

What careers value Chinese history expertise?

Expertise in Chinese history is valued in a surprising array of careers. Academia is a traditional path, with roles as professors and researchers at universities and colleges. Museums and cultural heritage institutions often seek curators, archivists, and educators with specialized knowledge of Chinese art and history. [dd61ls]

Beyond these, government agencies, particularly those involved in foreign affairs, diplomacy, intelligence, and cultural exchange, value deep regional expertise. Policy analyst roles in think tanks or non-governmental organizations focusing on East Asia also benefit from historical understanding. [tw34c0] In the private sector, journalism, international business, consulting, and translation services may seek individuals who can provide historical context and cultural insights related to China. [i8f9j1, r6hk5f, ia98df] The ability to analyze complex information, understand long-term trends, and appreciate cultural nuances are key skills derived from historical study.

The growing importance of China in global affairs means that a sophisticated understanding of its past is increasingly relevant across many sectors. Careers that involve research, analysis, communication, and cross-cultural understanding are all areas where Chinese history expertise can be a significant asset. Consider also the role of a

How transferable are sinology skills to other fields?

The study of Chinese history, and Sinology more broadly (the comprehensive study of China), cultivates a range of highly transferable skills. Critical thinking and analytical skills are paramount, as students learn to evaluate diverse sources, identify biases, construct arguments, and synthesize complex information. Research skills, including the ability to locate, assess, and interpret textual and material evidence, are also central to the discipline.