Theologian

A Career in Theology: Exploring Faith, Reason, and Society

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It delves into questions about God, humanity, salvation, and the meaning of existence, drawing upon sacred texts, tradition, reason, and experience. As an academic discipline, theology intersects with philosophy, history, sociology, anthropology, and ethics, offering a rich intellectual landscape for exploration. It is a field dedicated to understanding diverse religious traditions and their profound impact on cultures, societies, and individual lives.

Working as a theologian can be intellectually stimulating and deeply rewarding. You might find excitement in the meticulous analysis of ancient scriptures, uncovering layers of meaning relevant to contemporary life. Engaging in ethical debates, constructing frameworks for moral reasoning, or facilitating dialogue between different faith communities can also be compelling aspects of the work. Furthermore, the opportunity to contribute to scholarly understanding or guide communities in their spiritual journeys offers profound personal and professional satisfaction.

The Role of a Theologian

The work of a theologian involves rigorous intellectual inquiry and often, deep personal engagement with questions of faith, meaning, and ethics. It's a field that demands critical thinking, analytical prowess, and often, a nuanced understanding of history and culture.

Core Responsibilities and Activities

At its heart, theology involves the critical interpretation of religious texts, traditions, and beliefs. Theologians analyze sacred scriptures, historical documents, and philosophical arguments to understand and articulate concepts of the divine, human nature, and the cosmos. This often requires skills in hermeneutics, the theory and methodology of interpretation.

Many theologians also focus on developing ethical frameworks derived from religious principles. They examine moral questions related to social justice, bioethics, environmental stewardship, and personal conduct, aiming to provide guidance grounded in their respective traditions. Interfaith dialogue is another crucial area, where theologians work to foster mutual understanding and respect between different religious communities, analyzing points of convergence and divergence.

Research and writing are central activities, whether for academic publications, educational materials, or resources for religious communities. Teaching, either in universities, seminaries, or community settings, is also a common responsibility, involving the communication of complex ideas to diverse audiences. Some theologians engage directly in pastoral work, community leadership, or advisory roles within religious institutions or non-profits.

These courses offer insights into the interpretive methods and foundational texts central to theological study.

These books provide essential tools and background for textual analysis and understanding core theological concepts.

Areas of Specialization

Theology is a broad field with numerous areas of specialization. Biblical Studies focuses on the critical examination of the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) and the New Testament, involving linguistic analysis, historical context, and literary criticism. Scholars in this area might focus on specific books, genres, or historical periods.

Systematic Theology attempts to formulate an orderly, rational, and coherent account of the doctrines of a particular faith tradition. It addresses topics like the nature of God, Christology, soteriology (the study of salvation), and eschatology (the study of end times), often drawing heavily on philosophical concepts.

Comparative Religion, or Religious Studies, involves the systematic comparison of the doctrines and practices of the world's religions. Theologians in this area explore similarities and differences across traditions like Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and others, often focusing on themes like ritual, myth, scripture, or ethics across cultures.

Other specializations include historical theology (tracing the development of doctrines over time), moral theology or theological ethics (focusing on ethical reasoning and behavior), practical theology (examining religious practices and ministry), and contextual theologies (like liberation theology, feminist theology, or black theology) which interpret theological themes through the lens of specific social or cultural experiences.

These courses delve into specific religious traditions and the philosophical underpinnings often engaged by systematic theologians.

These texts offer foundational insights into major world religions and philosophical thought relevant to theology.

Institutional vs. Independent Paths

Theologians typically work within institutional settings like universities, seminaries, colleges, or religious organizations (churches, synagogues, mosques, dioceses, etc.). Academic theologians primarily engage in research, publishing, and teaching at the postsecondary level. Those working within religious institutions might focus on education, leadership, pastoral care, or policy development.

However, there is also scope for independent theological work. Some theologians operate as freelance writers, public intellectuals, consultants, or speakers. They might contribute to journals, author books for a general audience, advise organizations on ethical matters, or engage in public discourse on religion and society. This path requires significant self-direction, networking, and often, entrepreneurial skills.

The rise of digital platforms also enables independent theologians to build audiences through blogs, podcasts, or online courses, disseminating their work outside traditional institutional structures. While potentially offering more autonomy, independent work often lacks the stability and resources associated with institutional employment.

This course explores the intersection of theology and contemporary life, relevant for both institutional and independent paths.

This career path often involves work within religious institutions.

Formal Education Pathways

Pursuing theology, especially within academia or formal ministry, typically requires a structured educational journey. This path involves building foundational knowledge and developing sophisticated research and analytical skills.

Undergraduate Foundations

A bachelor's degree is usually the first step. While some universities offer undergraduate degrees specifically in Theology or Religious Studies, related fields provide excellent preparation. Degrees in Philosophy, History, Classics, Sociology, or Anthropology equip students with critical thinking, analytical reading, and writing skills essential for theological study.

Coursework in philosophy introduces logical reasoning and major ethical theories. History courses provide context for understanding the development of religious traditions and texts. Studying ancient languages like Greek, Hebrew, Latin, or Arabic can be highly advantageous, particularly for those interested in biblical studies or the history of specific traditions, as it allows for engagement with primary sources in their original form.

Developing strong research and writing abilities during undergraduate studies is crucial. Familiarity with library resources, databases, and scholarly citation methods forms the bedrock for future graduate work. Engaging with diverse perspectives and honing argumentation skills are key objectives at this stage.

These courses offer foundational knowledge in philosophy and ancient languages often required or recommended for theological studies.

Graduate Programs and Research

For academic careers or specialized ministry roles, graduate study is essential. Master's degrees, such as the Master of Arts (MA) in Theology or Religious Studies, Master of Theological Studies (MTS), or Master of Divinity (MDiv), deepen knowledge and refine research skills. An MDiv is often required for ordination in many Christian denominations.

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) is typically necessary for university-level teaching and advanced research. PhD programs involve intensive coursework, comprehensive examinations demonstrating mastery of the field, and the completion of a dissertation – a substantial piece of original scholarly research contributing new knowledge to the discipline.

Graduate programs demand advanced research capabilities. This includes proficiency in hermeneutics for textual interpretation, experience with archival research for historical theology, and skills in qualitative analysis for studying contemporary religious phenomena. Depending on the specialization, quantitative methods might also be relevant. Mastery of relevant ancient and modern languages is often a strict requirement.

These courses provide introductions to specific religious scriptures and historical contexts often explored at the graduate level.

These books represent the kind of in-depth scholarly work often encountered or produced in graduate studies.

Essential Research Techniques

Success in theological studies hinges on mastering specific research techniques. Hermeneutics, the art and science of interpretation, is fundamental for analyzing sacred texts and theological writings. This involves understanding literary genres, historical contexts, linguistic nuances, and the history of interpretation itself.

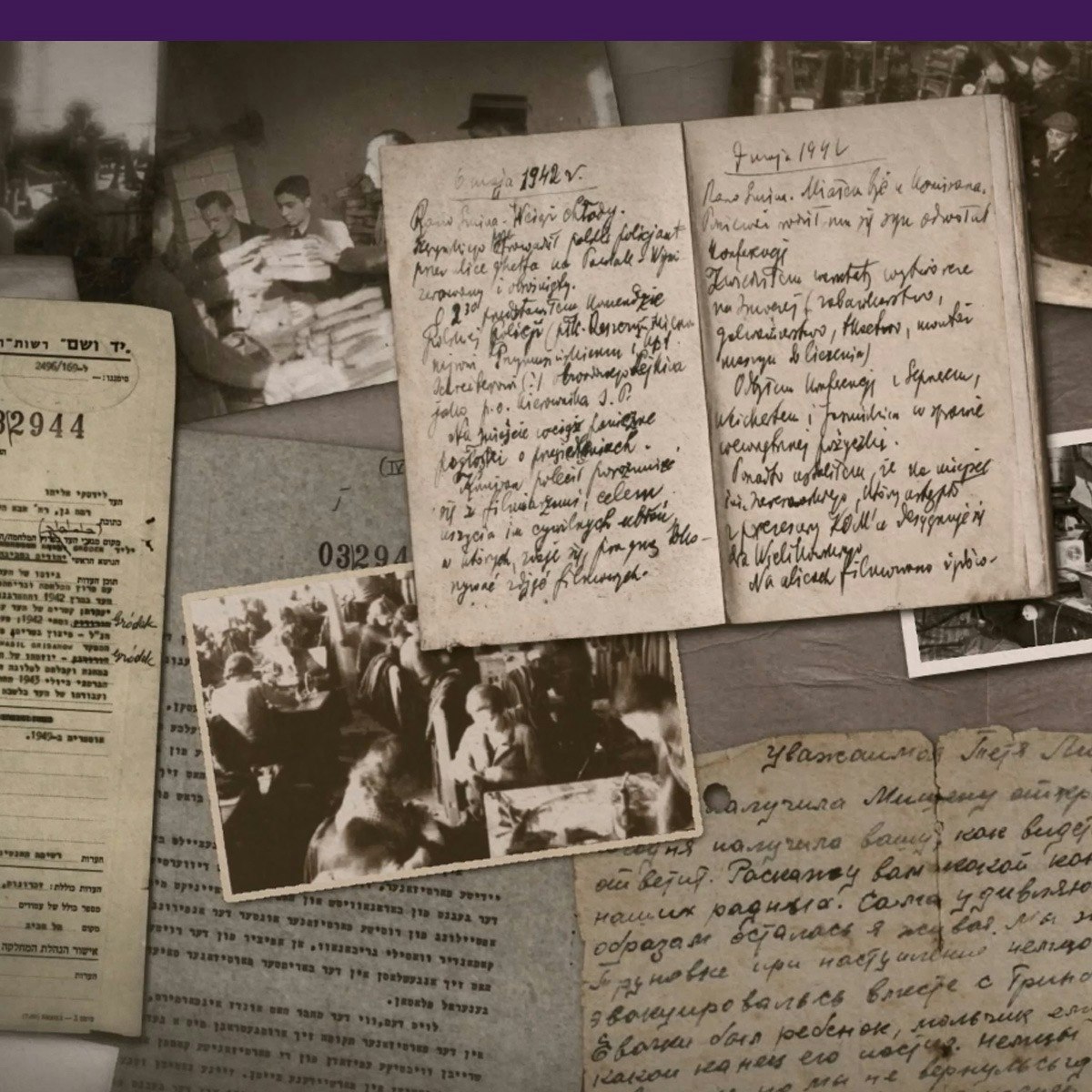

Archival work is crucial for historical theology. This requires locating, accessing, and analyzing primary source documents housed in libraries, archives, and special collections. Skills include paleography (reading old handwriting), understanding archival organization, and critically evaluating historical evidence.

Qualitative analysis methods, often borrowed from the social sciences, are increasingly used in practical theology and the study of contemporary religion. Techniques like interviews, participant observation, and content analysis help theologians understand lived religious experiences, community dynamics, and the impact of religion in society. Regardless of specialization, strong analytical reasoning and clear, persuasive writing are paramount.

These courses touch upon historical research methods and critical thinking applicable to theological inquiry.

This book is a classic text on the philosophy of science, relevant to understanding methodologies and paradigms in academic research.

Independent Learning Strategies

While formal education provides structure and credentials, dedicated individuals can pursue theological understanding independently. This path requires discipline, resourcefulness, and a commitment to rigorous self-assessment.

Engaging with Foundational Texts

The cornerstone of independent theological study is direct engagement with primary sources. This means reading foundational religious texts – the Bible, Quran, Vedas, Sutras, Talmud, etc. – thoughtfully and critically. Alongside scriptures, delve into the works of major theologians, philosophers, and historians relevant to the tradition(s) you are exploring.

Start with accessible translations and commentaries, gradually moving towards more scholarly editions. Don't just read; analyze. Take notes, summarize arguments, identify key themes, and compare different perspectives. Consider the historical and cultural context in which these texts were written and how interpretations have evolved over time.

Building this foundational knowledge takes time and patience. It's a cumulative process where understanding deepens with each text encountered. Be prepared to grapple with challenging ideas and unfamiliar concepts, revisiting materials as your knowledge grows.

These courses provide guided introductions to major religious scriptures, ideal starting points for independent learners.

These books represent foundational texts across different traditions, essential for independent study.

Leveraging Digital Resources and Online Courses

The digital age offers unprecedented resources for independent learners. Online course platforms provide access to university-level lectures and structured learning experiences, often taught by leading scholars. OpenCourser catalogs thousands of such courses across Humanities, Philosophy, and Religion, allowing you to compare syllabi, read reviews, and find materials suited to your interests.

Beyond courses, numerous digital libraries (like Project Gutenberg or university archives) offer free access to classic texts. Online journals, academic databases (sometimes accessible through public libraries), podcasts, and reputable websites dedicated to religious studies provide a wealth of information. You can use OpenCourser's features like "Save to List" to curate your own learning path (manage your lists here) combining courses, books, and other resources.

When designing your personal curriculum, aim for breadth and depth. Explore different traditions or dive deep into a specific area. Balance primary text reading with secondary sources (scholarly analysis) and consider incorporating courses on relevant languages or historical periods. Be discerning about sources, prioritizing academic and reputable materials.

These online courses offer structured learning on specific theological topics and related philosophical inquiries, perfect for supplementing independent study.

Developing Critical Analysis Independently

Learning independently means taking responsibility for developing critical analysis skills without the direct feedback of professors. This involves actively questioning assumptions (both your own and those in the texts), evaluating arguments for logical consistency and evidence, and considering alternative interpretations.

Engage with scholarly debates by reading book reviews, journal articles presenting different viewpoints, and critical commentaries. Try writing summaries, critiques, or comparative analyses of the materials you study. Joining online forums, discussion groups, or local reading circles focused on theology or religion can provide valuable interaction and feedback.

Seek out opportunities to present your ideas, perhaps through a personal blog or by participating in community discussions. The process of articulating your thoughts and responding to questions helps refine your understanding and analytical abilities. Be open to revising your views as you learn more – intellectual humility is key to growth.

These courses focus on critical thinking, ethical reasoning, and understanding diverse perspectives, skills vital for independent analysis.

This book explores how to approach spirituality outside traditional religious frameworks, potentially useful for independent thinkers.

Career Progression for Theologians

A career path in theology can unfold in various ways, often blending academic pursuits with practical application. Progression typically depends on education, experience, specialization, and individual career goals.

Early Career Opportunities

For those on an academic track, early career roles often involve gaining teaching and research experience after completing graduate studies. Positions like teaching fellowships, postdoctoral research appointments, or adjunct instructorships provide valuable experience while scholars work on publishing their research, often derived from their doctoral dissertation.

In non-academic settings, entry-level roles might include positions in religious education, youth ministry, administrative support within religious organizations, or assistant roles in non-profits focused on social justice or interfaith work. Some graduates may find roles in archives, libraries, or museums with religious collections.

Building a professional network is crucial during this phase. Attending conferences, joining scholarly societies, and connecting with established professionals in the field can open doors to future opportunities. Demonstrating strong communication, analytical, and interpersonal skills is key.

These courses cover areas relevant to early-career applications of theology, such as education and understanding specific communities.

Mid-Career Transitions and Advancement

As theologians gain experience and build their reputations, opportunities for advancement emerge. In academia, this often means securing tenure-track positions, progressing through assistant, associate, and full professorship ranks. Mid-career academics typically have established research profiles, significant publications (including books), and take on greater departmental or university service roles.

Outside academia, mid-career theologians might move into leadership positions within religious institutions, such as directors of education, senior pastors, or denominational administrators. Others leverage their expertise to transition into roles in publishing as editors, or into leadership positions within non-profits, foundations, or advocacy groups focused on ethics, human rights, or interfaith relations.

Some theologians establish themselves as public intellectuals, writing for broader audiences, giving public lectures, or consulting for media organizations. International opportunities may arise with ecumenical bodies, international NGOs, or academic institutions abroad, particularly for those with relevant language skills and cross-cultural expertise.

These courses explore leadership and communication within religious contexts, pertinent to mid-career advancement.

This book delves into the workings of a major religious institution, offering context for leadership roles.

These careers represent potential leadership or specialized roles accessible mid-career.

Alternative and Adjacent Career Paths

The skills developed through theological study – critical thinking, textual analysis, ethical reasoning, cross-cultural understanding, research, and communication – are highly transferable. This opens doors to various alternative career paths beyond traditional academic or ministerial roles.

Many graduates find fulfilling careers in non-governmental organizations (NGOs) working on issues like social justice, poverty alleviation, human rights, or environmental advocacy. Their understanding of ethics and diverse worldviews can be invaluable in program development, policy analysis, or community outreach.

Some theologians become cultural consultants, advising businesses or government agencies on religious diversity, ethical practices, or cross-cultural communication. Others pursue careers in journalism, writing, editing, or museum curation, specializing in religion, history, or ethics. Counseling, social work, and law are other fields where a theological background can provide a unique perspective and skill set, though these typically require additional specific qualifications.

According to data gathered by universities and career sites like Prospects.ac.uk, theology graduates find employment across diverse sectors including education, charity work, social services, government, finance, law, and media. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects growth in related fields like community and social service occupations, suggesting opportunities exist where theological skills are applicable, even if not explicitly required.

This course examines the intersection of religion, conflict, and peace, relevant for NGO and policy work.

This book explores business ethics, an area where theologians might serve as consultants.

Ethical Challenges in Theological Work

Engaging deeply with diverse beliefs, sensitive histories, and personal faith commitments brings unique ethical responsibilities and challenges for theologians.

Sensitivity in Comparative Studies

When studying and comparing different religious traditions, theologians must navigate the complex issue of cultural appropriation. It's essential to approach other faiths with respect, avoiding misrepresentation or the superficial adoption of symbols and practices removed from their original context. Representing traditions accurately and charitably requires careful research and humility.

Scholars must be mindful of power dynamics and historical relationships between different religious groups. Presenting non-Western or minority traditions solely through a Western academic lens can perpetuate biases. Ethical comparative work involves amplifying diverse voices from within each tradition and acknowledging the limitations of one's own perspective.

Engaging in interfaith dialogue requires sensitivity to different communication styles and theological frameworks. Building trust and fostering genuine understanding, rather than aiming for conversion or asserting superiority, should be the primary goal.

These courses deal with inter-religious understanding and the importance of cultural context.

Objectivity, Faith, and Bias

A central tension for many theologians, particularly those working in academic settings, is balancing personal faith commitments with the demands of scholarly objectivity. While personal belief can provide deep insight and motivation, it can also introduce bias into research and interpretation.

Maintaining academic integrity requires transparency about one's own standpoint and a rigorous commitment to evidence-based analysis. It involves engaging fairly with perspectives that challenge one's own beliefs and distinguishing between confessional statements and academic arguments. This doesn't necessarily mean suppressing personal faith, but rather employing critical self-awareness.

In fields like theological ethics, the line between description (what a tradition teaches) and prescription (what one ought to believe or do) can be blurry. Ethical theologians must clearly articulate their methodology and the basis for their normative claims, respecting the distinction between academic analysis and pastoral guidance.

These courses explore philosophical and ethical reasoning, highlighting the importance of intellectual rigor and self-awareness.

This book discusses differing worldviews, relevant to navigating objectivity and faith.

Interpreting Controversial Histories

The history of religious traditions includes periods and events that are ethically troubling or contested, such as instances of violence, persecution, or complicity in injustice. Theologians have an ethical responsibility to confront these difficult aspects honestly, avoiding hagiography or apologetics that minimize harm.

Interpreting controversial historical events requires careful contextualization without excusing wrongdoing. It involves acknowledging the suffering caused and analyzing the theological ideas or institutional structures that may have contributed to negative outcomes. This can be particularly challenging when dealing with foundational figures or cherished aspects of a tradition.

Presenting historical interpretations requires sensitivity to how different communities may understand and be affected by that history today. Responsible scholarship involves engaging with diverse historical narratives and acknowledging the ongoing impact of the past.

These courses examine historical events and interpretations with ethical dimensions.

Theologian in the Digital Age

Technology is reshaping how theological research is conducted, how religious knowledge is disseminated, and how faith communities interact. Theologians must engage critically and thoughtfully with these digital transformations.

Technology's Impact on Research Methods

Artificial intelligence (AI) and computational tools are beginning to impact theological research, particularly in textual analysis. Machine learning algorithms can analyze vast amounts of text, identifying patterns, linguistic features, and thematic connections in scriptures or theological corpora that might be missed by human readers. This can augment traditional hermeneutical methods, though it also raises questions about the role of interpretation.

AI tools can also assist in translating ancient languages or comparing manuscript variations. While powerful, these tools require careful oversight. Theologians need to understand the capabilities and limitations of AI, ensuring that technology serves, rather than dictates, interpretive and analytical goals. Ethical considerations regarding data bias in algorithms and the potential de-humanization of textual study are also emerging.

Digital humanities methods, more broadly, offer new ways to visualize data, map historical developments, and collaborate on large-scale research projects. Theologians increasingly need digital literacy to engage with these evolving methodologies.

These courses explore the intersection of technology, ethics, and human thought.

Digital Archives and Accessibility

The digitization of religious manuscripts, historical documents, and theological journals has revolutionized access to primary and secondary sources. Major initiatives by libraries, universities, and cultural institutions are making vast collections available online, breaking down geographical barriers for researchers.

Digital archives facilitate new kinds of research, allowing scholars to search across large datasets and compare texts easily. They also play a crucial role in preserving fragile materials. However, challenges remain regarding the quality of digitization, metadata standards, long-term digital preservation, and equitable access, especially for resources behind paywalls.

Theologians benefit immensely from these digital resources but must also engage critically with their curation and potential biases. Understanding digital archiving practices and supporting open-access initiatives are becoming important aspects of scholarly citizenship in the field.

This course touches upon manuscript studies, highlighting the importance of primary sources now often accessed digitally.

Online Communities and Dialogue

The internet provides numerous platforms for theological discussion, interfaith dialogue, and the formation of virtual religious communities. Social media, blogs, forums, and online learning platforms allow theologians to share their work with broader audiences and engage in public discourse.

These platforms facilitate connections across geographical boundaries, enabling collaboration and the exchange of diverse perspectives. Online interfaith dialogue initiatives can foster understanding and bridge divides, reaching participants who might not engage in traditional, face-to-face encounters. Some research suggests technology enhances accessibility and participation in religious services, particularly for younger generations or those with mobility issues.

However, the digital sphere also presents challenges. Online discussions can lack nuance, foster polarization, and spread misinformation. Maintaining respectful dialogue and ensuring the credibility of information requires careful moderation and critical engagement from participants. Theologians engaging online must navigate these complexities ethically and effectively.

This course looks at the relationship between religion and society, increasingly mediated by digital platforms.

This book explores societal shifts relevant to online community formation.

Global Theological Perspectives

Theology is not monolithic; its practice, study, and emphasis vary significantly across different cultural and geographical contexts. Understanding these global perspectives enriches the field and fosters cross-cultural understanding.

Diverse Educational Systems

Theological education systems differ markedly around the world. European universities often integrate theology faculties within public institutions, emphasizing historical-critical methods and philosophical engagement. North American systems include university-based religious studies departments (often more secular in approach) alongside denominational seminaries and divinity schools focused on ministry training and specific faith traditions.

In other regions, theological training might occur primarily within religious institutions, monasteries, or madrasas, with curricula deeply embedded in specific traditions and sometimes less influenced by Western academic methodologies. Understanding these structural differences is crucial for international collaboration and for evaluating scholarship from diverse contexts.

Global partnerships and exchange programs are increasingly important for fostering dialogue between these different educational approaches. Recognizing the strengths and limitations of various systems promotes a more comprehensive global understanding of theological inquiry.

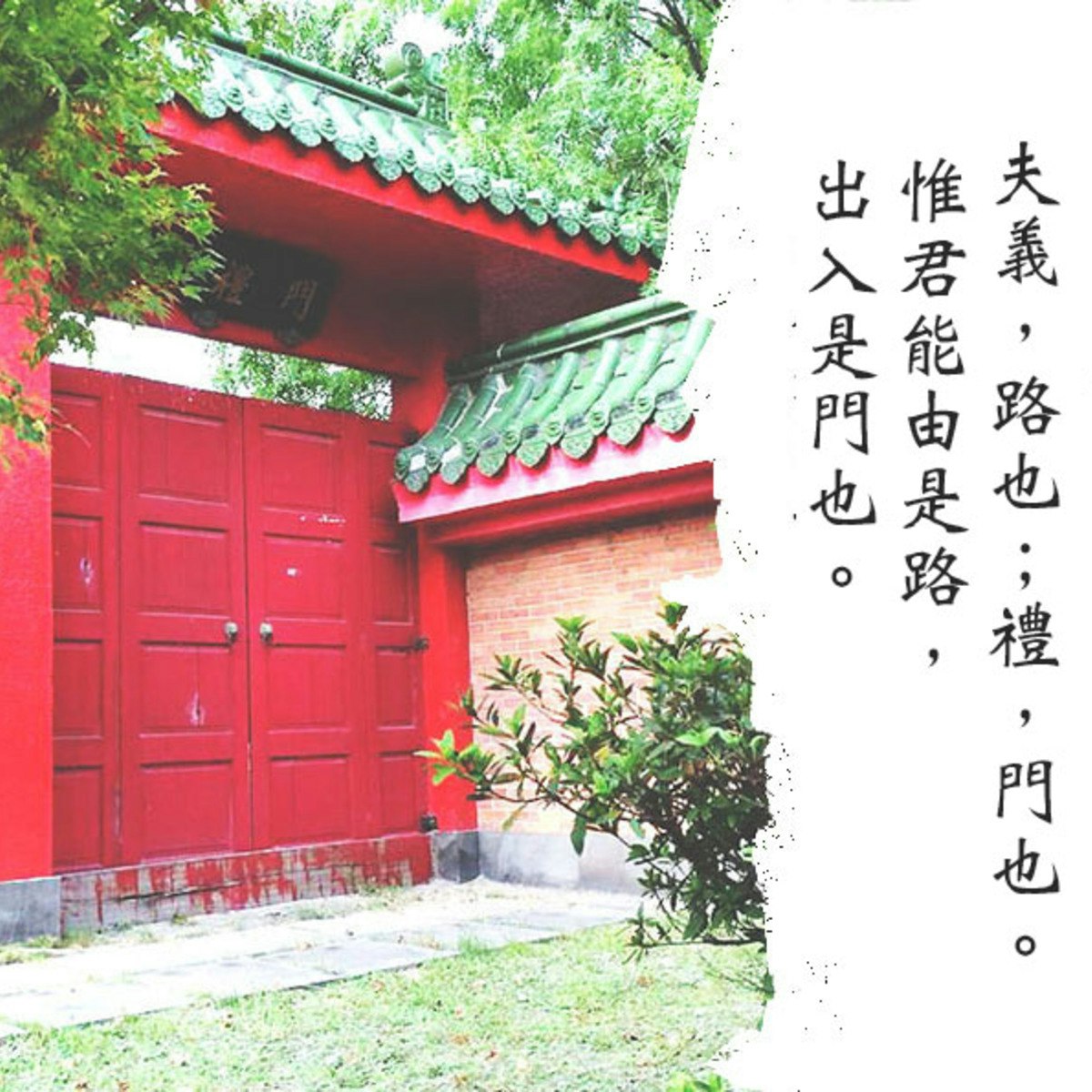

These courses offer glimpses into non-Western religious and philosophical traditions.

This foundational text represents a major Eastern tradition.

Emerging Non-Western Voices

While historically dominated by European and North American perspectives, theological scholarship is increasingly recognizing and engaging with vibrant traditions from Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. Contextual theologies, developed from the lived experiences of communities in the Global South, offer fresh insights and critiques of traditional Western frameworks.

Academic attention is growing for theological perspectives rooted in indigenous traditions, post-colonial contexts, and diverse interpretations of major world religions outside their regions of origin. This decentering of theology enriches the global conversation, highlighting diverse ways of understanding the divine, ethics, and community.

Engaging with these non-Western voices requires humility and a willingness to learn from different epistemologies and cultural assumptions. It pushes the boundaries of the discipline and fosters a more inclusive and globally relevant theological discourse.

These courses introduce perspectives from the Middle East and East Asia.

This book explores a period of Christianity outside its traditional Western centers.

Language and Cross-Cultural Research

Engaging deeply with global theological perspectives often necessitates language proficiency beyond the traditional Greek, Hebrew, and Latin. Scholars working on Islamic theology may need Arabic or Persian; those studying Hinduism or Buddhism might require Sanskrit, Pali, Tibetan, Chinese, or Japanese; research in African traditional religions often involves local languages.

Cross-cultural research demands more than just linguistic ability; it requires cultural competency. This includes understanding different social norms, communication styles, historical contexts, and conceptual frameworks. Ethical cross-cultural research involves building respectful relationships with local scholars and communities, ensuring collaborative partnerships rather than extractive research practices.

The challenges of translation – not just of words, but of concepts – are significant in cross-cultural theological work. Researchers must be sensitive to the nuances lost or gained in translation and strive for interpretations that are faithful to the original context while being intelligible to a wider audience.

These courses involve non-English languages or explore cross-cultural historical interactions.

Challenges Facing Modern Theologians

Despite its rich history and intellectual depth, theology today faces significant challenges related to funding, public perception, and navigating societal shifts.

Resource Constraints in the Humanities

Like many fields in the humanities, theology often faces funding constraints. Research grants for theological projects can be competitive and limited compared to STEM fields. University departments may face budget cuts, impacting faculty positions, library resources, and student support. Some analysis suggests federal funding for research touching on religion and spirituality, while substantial overall, may be declining or focused peripherally rather than centrally on R/S topics.

Seminaries and theological schools, particularly smaller independent institutions, can struggle with financial sustainability, relying heavily on donations and tuition. This economic pressure can impact faculty salaries, program offerings, and the ability to invest in necessary resources, including digital infrastructure for online learning, which became crucial during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Securing funding often requires theologians to demonstrate the broader societal relevance of their work, connecting theological insights to contemporary issues like ethics, social justice, or cultural understanding. Organizations like the Louisville Institute offer specific grants, but the overall landscape remains challenging.

Public Perception and Relevance

In increasingly secular societies, theology can face public skepticism regarding its relevance and academic rigor. Some perceive it as disconnected from practical concerns or based on untestable faith claims rather than objective inquiry. This perception can impact student enrollment, institutional support, and the perceived value of a theology degree in the broader job market.

Furthermore, negative actions or controversies associated with religious institutions can sometimes tarnish the public image of theology itself. Theologians often need to actively articulate the value of their discipline – its contribution to ethical reflection, cultural understanding, historical knowledge, and the exploration of fundamental human questions.

Overcoming skepticism requires demonstrating the intellectual depth of theology and its ability to engage constructively with science, philosophy, and pressing social issues. Highlighting the transferable skills gained through theological study (critical thinking, analysis, communication) also helps counter narrow perceptions of its applicability.

These courses address the relationship between religion, science, and philosophy, areas where theology engages broader public discourse.

This book tackles the relationship between science and belief systems.

Navigating Tradition and Modernity

Theologians often grapple with the tension between maintaining fidelity to historical traditions and engaging meaningfully with contemporary social values and scientific knowledge. Issues related to gender, sexuality, social justice, and scientific discoveries can create internal debates within religious traditions and challenges for theologians seeking to bridge tradition and modernity.

Balancing reverence for sacred texts and established doctrines with critical inquiry and evolving ethical sensibilities requires careful navigation. Some theologians focus on reinterpreting tradition in light of new contexts, while others emphasize defending traditional positions against perceived challenges from modern culture. This tension is inherent in a living tradition.

Effectively addressing these challenges involves deep engagement with both the sources of tradition and contemporary thought. It requires intellectual honesty, openness to dialogue, and the ability to articulate theological positions in ways that are both faithful to the tradition and relevant to contemporary life. According to Pew Research Center data, trends like declining religious affiliation in some regions alongside global growth in others highlight the complex landscape theologians must navigate.

These courses explore ethical dimensions and societal changes relevant to this tension.

These books address contemporary issues within specific religious contexts.

Frequently Asked Questions

Exploring a career in theology often raises practical questions about job prospects, skills, and requirements. Here are answers to some common inquiries.

Can theology lead to stable employment outside academia?

Yes, a theology degree develops transferable skills valuable in various sectors. Graduates find roles in non-profits, social services, counseling (often requiring further certification), chaplaincy (hospital, military, prison), secondary education, journalism, cultural consultancy, policy analysis, and even corporate ethics or human resources. While direct "theologian" roles outside academia are less common, the underlying skills in critical thinking, communication, research, and cross-cultural understanding are sought after. Job prospects in related fields like social services show average to above-average growth, according to BLS data referenced by university career pages.

How does theologian compensation compare to other humanities fields?

Compensation varies widely based on the specific role, sector (academic, non-profit, religious institution), location, and level of education (Bachelor's, Master's, PhD). Academic salaries for professors are generally comparable to other humanities disciplines, though potentially lower than STEM or professional fields. Salaries in ministry or non-profit work can range significantly. Some sources like ZipRecruiter place the average US salary for roles titled "Theology" around $63,000 (as of early 2025), while others like Comparably suggest higher averages ($111,000), likely reflecting different job title inclusions and experience levels. Specific roles like Minister or Professor have their own distinct salary ranges. Generally, advanced degrees lead to higher earning potential.

Is fluency in ancient languages absolutely necessary?

It depends heavily on the specific path. For academic careers, especially in biblical studies or historical theology focusing on primary sources, proficiency (often reading fluency) in languages like Greek, Hebrew, Latin, or Arabic is typically essential, particularly at the PhD level. For many ministry roles, comparative religion, or applied ethics specializations, deep language expertise may be less critical, though basic familiarity can still be beneficial. Undergraduate study might recommend, but not always require, language courses. Independent learners can engage meaningfully through translations, though original language access unlocks deeper levels of understanding.

These courses offer introductions to key ancient languages for theological study.

Do theologians need formal religious affiliation?

For roles within specific religious institutions (like clergy or denominational leadership), formal affiliation and adherence to that tradition's beliefs are almost always required. However, in academic religious studies departments at secular universities, personal religious affiliation is generally not a requirement; the focus is on scholarly study *of* religion, regardless of the researcher's personal beliefs. Theologians working in interfaith dialogue, non-profits, or consulting roles may or may not have personal affiliations, but require deep knowledge and respect for diverse traditions.

How transferable are theological research skills to other sectors?

Highly transferable. Theological training cultivates strong skills in critical thinking, complex text analysis, research methodologies (historical, textual, qualitative), ethical reasoning, argumentation, written and oral communication, and understanding diverse cultural perspectives. These abilities are valued in fields like law, policy analysis, journalism, education, non-profit management, market research, conflict resolution, and any role requiring deep analytical thought and nuanced communication.

What emerging fields intersect with theology?

Several fields are showing increased intersection with theology. Digital Humanities brings computational methods to textual and historical analysis. Bioethics constantly engages theological perspectives on life, health, and technology. Environmental Ethics draws on religious traditions for concepts of stewardship and creation care. Neurotheology explores the neural basis of religious experience. Artificial Intelligence ethics raises questions about consciousness, personhood, and values that intersect with theological anthropology. Peace and Conflict Studies increasingly incorporates religious dimensions in understanding and resolving conflicts.

This course explores an area where theology intersects with contemporary science and philosophy.

Embarking on a path in theology, whether through formal education or independent study, is a journey into profound questions about humanity, divinity, and the world we inhabit. It demands intellectual rigor, ethical sensitivity, and often, personal reflection. While challenges exist, the pursuit offers rich rewards in understanding and the potential to contribute meaningfully to academic discourse, community life, or broader societal understanding. Resources like OpenCourser can significantly aid this journey by providing access to a vast library of relevant courses and books.