Analyst

Exploring a Career as an Analyst

The term "Analyst" encompasses a wide range of roles centered around a core function: interpreting information to drive better decision-making. Analysts are the sense-makers within organizations, examining data, identifying trends, uncovering insights, and translating complex findings into actionable recommendations. They work across nearly every industry, applying their skills to solve problems, optimize processes, evaluate opportunities, and shape strategy.

What makes the analyst path engaging is the detective work involved. You might find excitement in diving into datasets to find hidden patterns, satisfaction in building a compelling case based on evidence, or fulfillment in seeing your insights lead to tangible results. The field is dynamic, constantly evolving with new tools and techniques, offering continuous learning opportunities for those with a curious mind.

Introduction to Analyst Roles

What Does an Analyst Do?

At its heart, an analyst role involves gathering, cleaning, interpreting, and communicating information. Analysts act as intermediaries between raw data and decision-makers. They use various tools and methodologies to transform numbers and observations into meaningful narratives that guide business actions, policy choices, or investment strategies.

The specific tasks vary significantly depending on the type of analyst and the industry. However, common threads include identifying relevant questions, sourcing appropriate data, applying analytical techniques (from simple spreadsheets to complex statistical models), visualizing findings, and presenting conclusions clearly to stakeholders who may not have a technical background.

Ultimately, the goal is to provide clarity in the face of complexity and uncertainty. Analysts help organizations understand past performance, monitor current operations, predict future outcomes, and make informed choices to achieve their objectives.

Where Do Analysts Work?

Analysts are in demand across virtually all sectors. Finance relies heavily on financial analysts for investment research, risk management, and corporate finance. The technology sector employs data analysts and business analysts to understand user behavior, improve products, and guide strategy. Healthcare utilizes analysts for clinical research, operational efficiency, and health informatics.

Other major employers include consulting firms, government agencies, marketing and advertising companies, retail businesses, manufacturing operations, and non-profit organizations. The skills of an analyst – critical thinking, quantitative reasoning, and effective communication – are highly transferable, making it a versatile career choice with broad applicability.

You can find analyst roles in large multinational corporations, nimble startups, research institutions, and public sector bodies. The environment might range from fast-paced trading floors to collaborative tech campuses or policy-focused government offices.

Distinguishing Between Analyst Types

While united by the core function of analysis, different types of analysts focus on specific domains. A Business Analyst often bridges the gap between business needs and technical solutions, focusing on process improvement and requirements gathering. A Data Analyst typically works more directly with large datasets, using programming and statistical tools to extract insights and build visualizations.

A Financial Analyst concentrates on financial data, evaluating investments, performing valuations, and forecasting economic trends. An Operations Research Analyst uses mathematical modeling and optimization techniques to improve efficiency in areas like logistics and supply chain management.

These are just a few examples, and many roles blend aspects of each. Understanding these distinctions can help you align your interests and skills with the right type of analyst career path.

Key Responsibilities of Analysts

Gathering and Interpreting Data

A fundamental responsibility for any analyst is acquiring the right data. This might involve querying databases using SQL, extracting information from company systems (like CRM or ERP software), conducting surveys, researching public sources, or even setting up experiments to generate new data.

Once gathered, data rarely arrives in perfect condition. Analysts spend considerable time cleaning, transforming, and structuring data to make it suitable for analysis. This critical step ensures accuracy and reliability. Interpretation involves applying statistical methods, domain knowledge, and critical thinking to understand what the data signifies in the context of the problem being addressed.

This interpretation phase is where analysts add significant value, moving beyond simple reporting to uncover underlying causes, trends, and potential implications. It requires both technical proficiency and sound judgment.

These courses provide foundational knowledge in statistics and data handling, crucial for effective interpretation.

Reporting and Communicating Findings

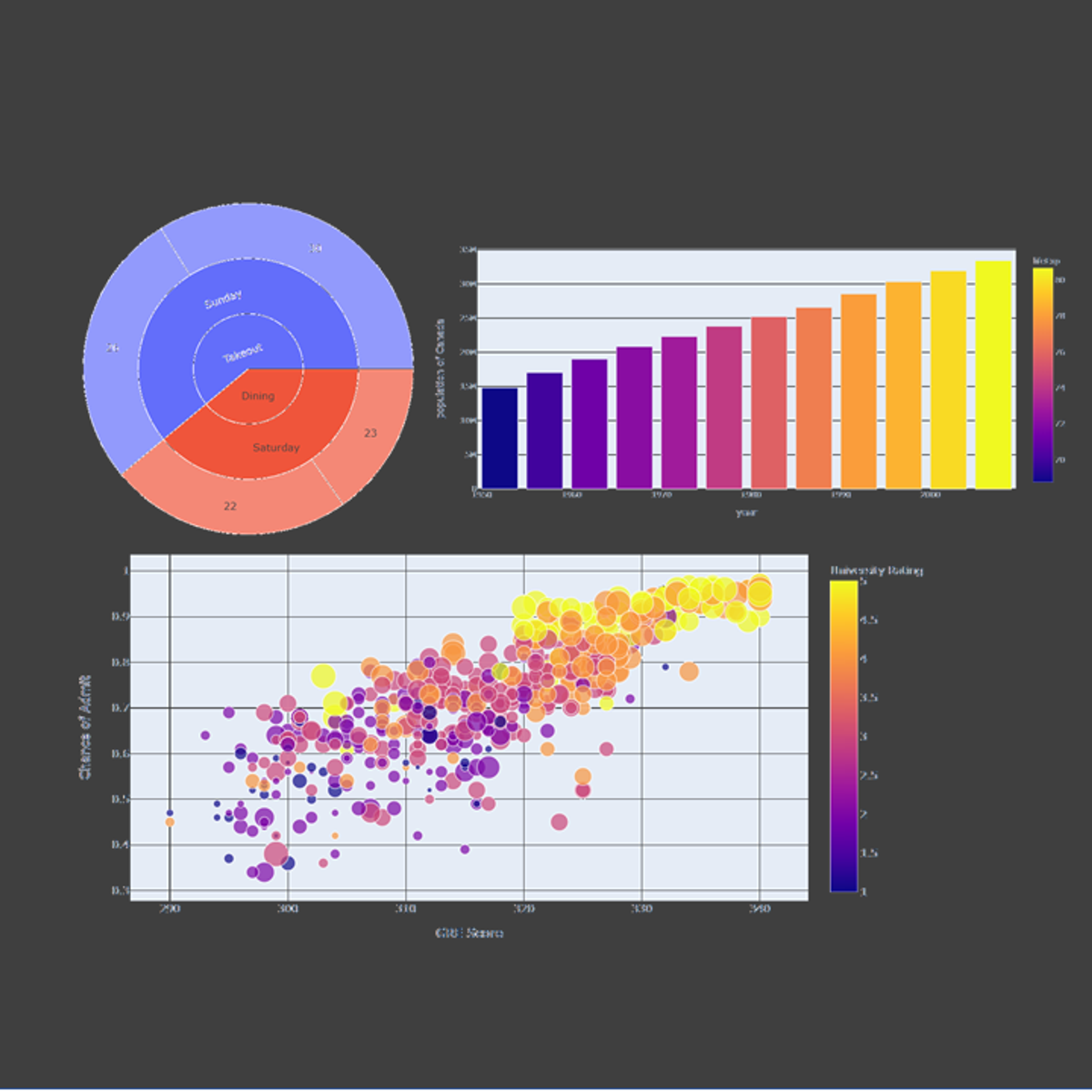

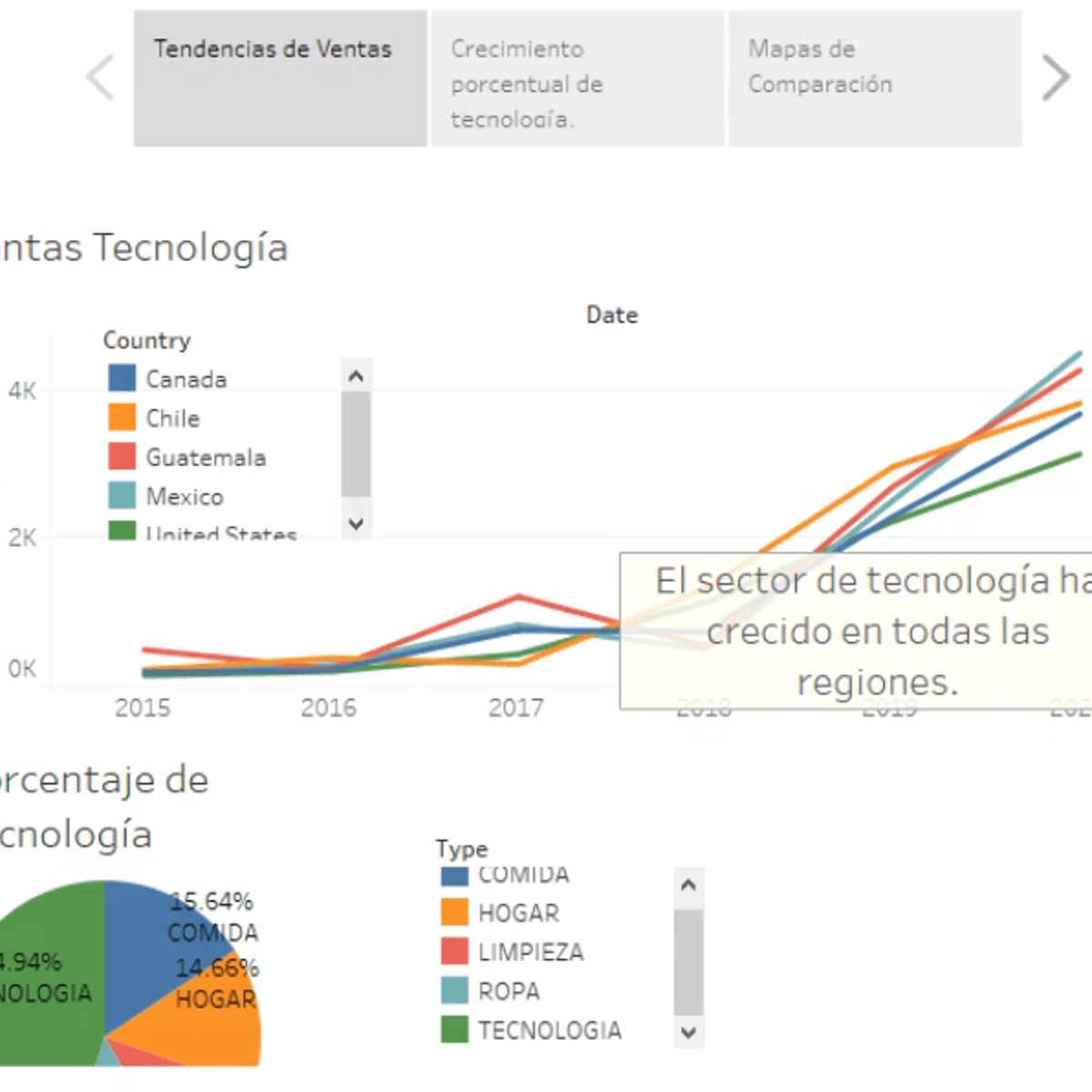

Analysis is only useful if its findings can be clearly communicated to those who need to act on them. Analysts must effectively translate complex results into understandable insights for various audiences, including managers, executives, clients, or technical teams. This often involves creating reports, dashboards, and presentations.

Data visualization plays a crucial role here. Using tools like Tableau or Power BI, analysts create charts and graphs that highlight key trends and make data more accessible. Strong writing and presentation skills are essential for conveying the story behind the data and supporting recommendations with evidence.

Effective communication ensures that the analytical work translates into real-world impact, influencing decisions and driving change within the organization.

Developing strong presentation and communication skills is vital for analysts. These courses focus on crafting compelling narratives and delivering impactful presentations.

Solving Problems with Data

At its core, analysis is about solving problems or answering questions. Analysts employ structured approaches to tackle challenges. This might involve defining the problem clearly, forming hypotheses, identifying the data needed to test them, conducting the analysis, and evaluating potential solutions.

Frameworks like root cause analysis, SWOT analysis, or cost-benefit analysis might be used depending on the context. Analysts need strong critical thinking and logical reasoning skills to break down complex issues, assess evidence objectively, and develop sound recommendations.

(Note: Portuguese, focuses on Critical Thinking)They often work collaboratively with other teams to understand the nuances of the problem and ensure that the proposed solutions are practical and aligned with organizational goals.

Types of Analysts and Specializations

Comparing Common Analyst Roles

Understanding the nuances between different analyst roles can guide your career exploration. Business Analysts focus on understanding business needs, processes, and systems. They elicit requirements, document workflows, and facilitate communication between business stakeholders and IT or development teams.

Data Analysts dive deep into data using statistical methods and programming tools like Python or R. They clean datasets, perform exploratory analysis, build dashboards, and communicate quantitative insights. Their focus is often on understanding trends, customer behavior, or operational performance through data.

Financial Analysts deal specifically with financial data to support investment decisions, assess company performance, manage risk, and forecast financial outcomes. They often require strong knowledge of accounting, economics, and financial markets. Operations Research Analysts apply advanced mathematical and analytical methods to optimize complex systems like supply chains, scheduling, or resource allocation.

Emerging Analyst Specializations

The field of analysis is constantly evolving. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are creating new opportunities for analysts who can work with these technologies, interpret model outputs, and apply AI to business problems. Roles like AI Analyst or Machine Learning Analyst are becoming more common.

Sustainability is another growing area, with organizations hiring Sustainability Analysts to measure environmental impact, track ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) metrics, and develop strategies for sustainable practices. Cybersecurity Analysts focus on protecting information systems by analyzing threats, monitoring networks, and responding to incidents.

As technology and business needs shift, new specializations will continue to emerge, requiring analysts to adapt and develop new skills. Staying curious and embracing lifelong learning is key in this dynamic field.

Industry-Specific Analyst Roles

Beyond generalist roles, many industries have specialized analyst positions. In healthcare, Healthcare Analysts or Health Informatics Analysts work with patient data, clinical trial results, and operational metrics to improve patient care and efficiency. Government agencies employ Policy Analysts to evaluate the impact of legislation and inform public policy decisions.

Marketing Analysts study consumer behavior, campaign effectiveness, and market trends to optimize marketing strategies. Market Research Analysts design surveys, analyze competitor activities, and forecast market demand to guide product development and business expansion. These roles often require deep domain expertise in addition to core analytical skills.

Exploring specific industries that interest you can reveal specialized analyst roles that align with your passions. OpenCourser's Business and Data Science categories offer courses relevant to many of these specializations.

Formal Education Pathways

Relevant Degrees

A bachelor's degree is typically the minimum educational requirement for entry-level analyst positions. Common fields of study include Business Administration, Economics, Finance, Statistics, Mathematics, Computer Science, or related quantitative fields. These programs provide foundational knowledge in areas like quantitative methods, critical thinking, and business principles.

For more specialized or advanced roles, particularly in data science or quantitative finance, a master's degree may be preferred or required. Programs in Analytics, Data Science, Business Analytics (MBAn), Finance, Statistics, or Operations Research offer deeper technical training and specialized knowledge.

Some analyst roles, especially in research or academia, may require a Ph.D. This path involves extensive research and prepares individuals for highly specialized analytical work or thought leadership positions.

Certifications for Analysts

Professional certifications can enhance your credentials and demonstrate expertise in specific areas of analysis. For Financial Analysts, the Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) designation offered by the CFA Institute is highly respected globally.

Business Analysts might pursue certifications like the Certified Business Analysis Professional (CBAP) from the International Institute of Business Analysis (IIBA). For analytics professionals, the Certified Analytics Professional (CAP) designation signifies a broad understanding of the end-to-end analytics process.

While not always required, certifications can signal commitment to the profession, provide structured learning, and potentially improve career prospects or earning potential, depending on the industry and specific role.

This course offers a certification related to digital assets, a niche but growing area for analysts.

Research Opportunities

For those pursuing advanced degrees like a Master's or Ph.D., research opportunities are integral. Working on research projects allows students to apply analytical techniques to novel problems, contribute to knowledge in their field, and develop deep expertise.

Research might involve statistical modeling, developing new algorithms, analyzing large datasets, or evaluating policy impacts. These experiences are highly valuable for roles requiring advanced analytical capabilities, such as quantitative analyst positions in finance or data scientist roles in tech.

Presenting research at conferences or publishing in academic journals further builds credibility and demonstrates strong analytical and communication skills. Even without pursuing a Ph.D., contributing to research projects during undergraduate or Master's studies can strengthen an analyst's profile.

Skill Development for Aspiring Analysts

Essential Technical Skills

Technical proficiency is crucial for most analyst roles. Proficiency in Microsoft Excel, including advanced functions like VLOOKUP, pivot tables, and data modeling, is often a baseline expectation. Knowledge of databases and the ability to query them using SQL is essential for accessing and manipulating data.

For roles involving more complex analysis or larger datasets, programming skills in languages like Python (with libraries such as Pandas, NumPy, Scikit-learn) or R are increasingly important. Familiarity with data visualization tools like Tableau or Power BI allows analysts to create compelling visual reports and dashboards.

Statistical knowledge, including understanding concepts like hypothesis testing, regression analysis, and probability, forms the backbone of sound analytical work.

These courses cover essential technical tools and concepts frequently used by analysts.

Cultivating Soft Skills

While technical skills are necessary, soft skills often differentiate successful analysts. Critical thinking is paramount – the ability to question assumptions, evaluate evidence objectively, and reason logically. Problem-solving involves identifying issues, exploring potential causes, and developing creative, data-backed solutions.

Communication skills are vital for translating technical findings into clear, concise language for non-technical audiences. This includes written communication (reports, emails), verbal communication (meetings, discussions), and presentation skills. Collaboration is also key, as analysts often work with diverse teams across an organization.

Developing business acumen – understanding the industry, company strategy, and operational context – helps analysts frame their work effectively and ensure its relevance.

Acquiring Domain-Specific Knowledge

Beyond general analytical skills, understanding the specific industry or functional area you work in (domain knowledge) significantly enhances an analyst's effectiveness. A financial analyst needs to understand financial markets and accounting principles. A healthcare analyst benefits from knowing medical terminology and healthcare systems.

Domain knowledge allows analysts to ask better questions, interpret data within its proper context, identify relevant metrics, and communicate more effectively with subject matter experts. It helps bridge the gap between technical analysis and real-world application.

This knowledge can be gained through work experience, industry-specific training, reading industry publications, or taking specialized courses. Online courses on platforms like OpenCourser offer pathways to learn about various domains, from Finance & Economics to Health & Medicine.

These courses provide insights into specific domains where analysts work.

(Real Estate/Finance) (Energy Sector) (Public Sector/Accounting)Leveraging Online Learning and Projects

Online courses provide accessible and flexible ways to build foundational knowledge and acquire specific technical skills. Platforms like OpenCourser aggregate thousands of courses, allowing you to find resources on SQL, Python, statistics, data visualization, and various business domains.

Supplementing coursework with hands-on projects is crucial for solidifying skills and building a portfolio. You can find public datasets online (e.g., Kaggle, government open data portals) and apply your skills to analyze them. Documenting your projects on platforms like GitHub or a personal blog demonstrates practical ability to potential employers.

For those pivoting careers, online learning combined with project work offers a structured path to gain necessary competencies. It requires discipline, but the wealth of available resources makes self-directed learning a viable option for aspiring analysts. OpenCourser's Learner's Guide offers tips on structuring your learning and staying motivated.

These courses focus on practical application and project-based learning.

Career Progression for Analysts

Typical Career Trajectory

The career path for an analyst often follows a progression from entry-level to more senior roles. An entry-level or Junior Analyst typically works under supervision, focusing on tasks like data gathering, basic analysis, and report generation. With experience, they become an Analyst, handling more complex tasks independently and contributing to interpretations.

A Senior Analyst takes on greater responsibility, leading projects, mentoring junior analysts, tackling ambiguous problems, and presenting findings to higher-level stakeholders. Beyond this, paths can diverge. Some may become Lead Analysts or Principal Analysts, serving as deep technical experts in a specific domain.

Others move into management roles, overseeing teams of analysts as an Analytics Manager or Director. The trajectory depends on individual skills, interests, and organizational structure.

Timelines and Advancement

Progression timelines vary based on performance, industry, company size, and educational background. Generally, moving from a Junior Analyst to an Analyst role might take 1-3 years. Advancing to a Senior Analyst position often requires another 3-5 years of experience.

Factors influencing advancement include consistently delivering high-quality work, demonstrating initiative, developing strong technical and soft skills, building domain expertise, and effectively communicating impact. Pursuing advanced degrees or relevant certifications can sometimes accelerate progression.

Networking within the company and industry, seeking mentorship, and proactively taking on challenging projects can also contribute to faster career growth. Patience and continuous learning are key elements for long-term advancement.

Transitions to Other Roles

The skills developed as an analyst provide a strong foundation for various other career paths. Many analysts transition into management roles, leveraging their understanding of data and business processes to lead teams or departments.

Other common transitions include moving into Project Management, Product Management (especially for business or data analysts working closely with product teams), Data Science (for those with strong statistical and programming skills), or Strategy roles that require analytical thinking and data-driven decision making.

Some analysts leverage their expertise to become consultants, advising multiple clients on analytical challenges. The versatility of the analyst skill set opens doors to diverse opportunities across different functions and industries.

Analyst Tools and Technologies

Data Visualization Software

Communicating insights effectively often relies on powerful data visualization tools. Software like Tableau, Microsoft Power BI, and Qlik Sense allow analysts to create interactive dashboards, charts, and maps from various data sources. These tools help translate complex data into easily digestible visual stories.

Proficiency in at least one major visualization platform is a valuable skill for many analyst roles, particularly those involving reporting and business intelligence. These tools enable self-service analytics for stakeholders and facilitate data exploration.

These courses offer hands-on experience with popular visualization tools.

(Note: Spanish) (Note: French, covers Google Data Studio/Looker Studio)Statistical Analysis Software and Languages

For more advanced statistical analysis and modeling, analysts often use specialized software or programming languages. R (with its environment RStudio) is a popular open-source language widely used in academia and data science for statistical computing and graphics. Python, with libraries like SciPy and Statsmodels, is another versatile option favored for its integration with broader data science workflows.

Traditional statistical software packages like SAS and SPSS are still common in certain industries, particularly in clinical research, finance, and market research. Proficiency in these tools enables analysts to perform complex statistical tests, build predictive models, and handle sophisticated analytical tasks.

Industry-Specific Platforms

Depending on the industry and specific role, analysts may need proficiency in specialized platforms. Financial analysts frequently use Bloomberg Terminal or Refinitiv Eikon for market data and analysis. Marketing analysts might work with web analytics platforms like Google Analytics or CRM systems like Salesforce.

Supply chain analysts might use specialized optimization software or ERP systems like SAP. Understanding the key platforms used within a target industry can be a significant advantage. Familiarity often comes from on-the-job training, but introductory online courses can provide a valuable head start.

(Project/Work Management Platform)Ethical Considerations in Analysis

Data Privacy and Security

Analysts often work with sensitive information, making data privacy and security paramount. They must be aware of and comply with relevant regulations like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europe or the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA). This includes understanding principles of data minimization, purpose limitation, and user consent.

Proper handling of personally identifiable information (PII) is crucial. Analysts need to employ techniques like anonymization or pseudonymization where appropriate and ensure data is stored and transmitted securely. Adherence to company policies and legal requirements regarding data handling is a fundamental ethical responsibility.

(Touches on human factors in security) (Covers technical aspects of data integrity)Mitigating Bias in Analysis

Data can reflect historical biases present in society or in data collection processes. Analysts have an ethical obligation to be aware of potential biases in their data sources, analytical methods, and interpretations. Failure to address bias can lead to unfair or discriminatory outcomes.

This involves critically examining data for representativeness, scrutinizing algorithms for potential biases, and considering the potential impact of analysis on different groups. Transparency about limitations and potential biases in the analysis is also important. Striving for fairness and equity should guide analytical work.

These courses discuss biases, which is crucial for ethical analysis, though one is finance-focused.

(Covers the accuracy fallacy, related to misinterpretation)Ensuring Integrity and Transparency

Maintaining professional integrity is essential. Analysts must strive for objectivity in their work, avoiding conflicts of interest that could compromise their analysis. Findings should be reported accurately and honestly, even if they contradict expectations or desired outcomes.

Transparency in methodology is also key. Analysts should be able to explain how they arrived at their conclusions, including the data sources used, analytical techniques applied, and assumptions made. This allows others to understand, evaluate, and potentially reproduce the analysis.

Upholding ethical standards builds trust in the analytical process and ensures that data-driven decisions are made responsibly.

Future of Analyst Careers

Impact of AI and Automation

Artificial intelligence (AI) and automation are undoubtedly transforming the analyst landscape. Routine tasks like data cleaning, basic reporting, and even some exploratory analysis are becoming increasingly automated. However, this doesn't necessarily mean the end of analyst roles. Instead, it shifts the focus towards higher-value activities.

Analysts will increasingly work alongside AI tools, leveraging them to handle repetitive tasks and generate initial insights. The critical skills will involve interpreting AI outputs, asking the right questions, understanding complex business contexts, communicating nuanced findings, and exercising ethical judgment – areas where human expertise remains crucial. According to insights from firms like McKinsey, adaptability and upskilling will be vital.

New roles focused on managing, interpreting, and ethically deploying AI within analytical workflows are likely to emerge.

These courses explore the growing intersection of AI and business roles.

Growing Demand Sectors

The demand for analysts remains strong, particularly in sectors experiencing rapid growth and digital transformation. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), fields like management, scientific, and technical consulting services, healthcare, finance and insurance, and information technology are projected to have significant job growth for various analyst roles (e.g., Management Analysts, Operations Research Analysts, Market Research Analysts).

The increasing volume of data generated across all industries fuels the need for professionals who can turn that data into actionable insights. Areas like e-commerce, renewable energy, cybersecurity, and personalized medicine are also likely to drive demand for specialized analytical talent.

Analysts who combine technical skills with strong domain knowledge in these high-growth sectors will likely find ample opportunities.

Rise of Hybrid Roles

The lines between traditional analyst roles and related fields like data science and data engineering are becoming increasingly blurred. Organizations are seeking professionals with broader skill sets who can bridge gaps between different functions. This leads to the emergence of hybrid roles.

Examples include Analytics Engineers who combine data modeling, engineering, and analysis, or Machine Learning Analysts who possess both analytical and ML implementation skills. Analysts may need to develop skills traditionally associated with data scientists (e.g., advanced modeling, machine learning) or data engineers (e.g., data pipelines, cloud platforms) to remain competitive.

This trend underscores the importance of continuous learning and adaptability. Embracing a wider range of technical and analytical competencies will be advantageous for future career prospects.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I become an analyst without a related degree?

Yes, it is possible, especially for certain types of analyst roles. While many employers prefer candidates with degrees in quantitative fields like statistics, economics, business, or computer science, relevant skills and experience can often compensate. Building a strong portfolio of projects demonstrating your analytical abilities is crucial.

Completing online courses, earning certifications, and gaining practical experience through internships or entry-level data-related roles can help bridge the gap. Highlighting transferable skills from previous careers (e.g., problem-solving, critical thinking) is also important. It might be more challenging for highly quantitative roles (like Quant Analyst) but feasible for many Business or Data Analyst positions.

(Focuses on learning strategies)What's the earning potential for entry-level analysts?

Earning potential varies significantly based on location, industry, company size, specific role, and educational background. According to data from sources like the BLS and salary surveys from firms like Robert Half, entry-level salaries for roles like Data Analyst or Financial Analyst typically fall in a broad range, often starting from $55,000 to $75,000 USD per year, but this can fluctuate.

Salaries tend to be higher in high-cost-of-living areas and in industries like finance and technology. Roles requiring advanced degrees or highly specialized skills usually command higher starting salaries. It's best to research salary benchmarks for specific analyst roles in your target industry and geographic location.

How competitive are analyst positions?

Analyst roles are generally in demand, but competition can be significant, especially for entry-level positions at well-known companies. The level of competition varies by industry and specialization. Roles in popular fields like tech and finance tend to attract many applicants.

To stand out, candidates need a combination of relevant education, strong technical skills (SQL, Excel, often Python/R, visualization tools), demonstrable analytical abilities (showcased through projects or experience), good communication skills, and ideally some domain knowledge. Networking and internships can also provide a competitive edge.

While challenging, the broad applicability of analyst skills means opportunities exist across many sectors for persistent and well-prepared candidates.

Do analysts need programming skills?

It depends on the specific role. Many Business Analyst roles may rely more heavily on tools like Excel, SQL, and requirements gathering techniques, with less emphasis on programming. However, for Data Analysts, Quantitative Analysts, Operations Research Analysts, and increasingly Financial Analysts, programming skills in Python or R are often essential.

These languages are used for data manipulation, statistical analysis, modeling, and automation. Even if not strictly required initially, learning programming can significantly enhance an analyst's capabilities and career prospects. Familiarity with Programming concepts is becoming a valuable asset across the board.

What industries hire the most analysts?

Several industries are major employers of analysts. Finance and Insurance (Financial Analysts, Risk Analysts), Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services (Management Analysts, Consultants, Data Analysts), Information Technology (Data Analysts, Business Analysts, Systems Analysts), Healthcare and Social Assistance (Healthcare Analysts, Data Analysts), and Government (Policy Analysts, Operations Research Analysts) are consistently large employers.

Manufacturing, Retail Trade, and Wholesale Trade also employ significant numbers of analysts, particularly Operations Analysts and Marketing Analysts. The demand reflects the broad need for data-driven decision-making across the economy.

How does certification impact career advancement?

The impact of certifications varies. In some fields, like finance with the CFA, a specific certification is highly valued and can significantly boost career advancement and earning potential. In other areas, like general data analysis or business analysis, certifications (like CAP or CBAP) can be beneficial but might be weighed alongside experience and demonstrated skills.

Certifications demonstrate commitment, provide structured knowledge, and can help differentiate candidates. However, they are rarely a substitute for practical experience and proven ability. They are often most valuable when combined with a solid educational foundation and relevant work history.

Embarking on or transitioning into an analyst career requires dedication to learning and skill development. Whether pursuing formal education or leveraging online resources, the key is to build a solid foundation in analytical thinking, technical tools, and effective communication. While challenges exist, the ability to derive meaning from data is an increasingly valuable skill in today's world, offering rewarding opportunities for those willing to put in the effort. OpenCourser provides a vast library of courses related to analysis to support your learning journey.