Epidemiologist

vigating the World of Epidemiology: A Career Guide

Epidemiology is the cornerstone of public health, a field dedicated to understanding the patterns, causes, and effects of health and disease conditions in defined populations. It is the science that underpins public health interventions and policy decisions. Epidemiologists are, in essence, disease detectives. They investigate the origin and spread of illnesses, identify risk factors, and develop strategies to prevent and control diseases, ultimately working to improve public health outcomes.

The work of an epidemiologist can be profoundly engaging and exciting. Imagine being at the forefront of solving complex public health mysteries, much like a detective piecing together clues to solve a case. Epidemiologists often find themselves working on a diverse range of issues, from investigating outbreaks of infectious diseases like influenza or Ebola to studying the long-term impacts of environmental exposures or the effectiveness of new vaccines and treatments. Their findings directly influence public health policies and can lead to tangible improvements in community well-being, making it a career with a significant real-world impact.

Introduction to Epidemiology

This article serves as a comprehensive guide for anyone considering a career in epidemiology. We will explore the definition and scope of this vital field, delve into its historical context, and highlight its crucial role in modern public health and disease prevention.

What Exactly is Epidemiology?

At its core, epidemiology is the study of how often diseases occur in different groups of people and why. It involves observing, recording, and analyzing the distribution and determinants of health-related states or events – not just diseases, but also injuries, and even positive health outcomes – in specified populations. This information is then applied to control health problems. Think of it like medical detective work on a large scale. Instead of focusing on one patient, epidemiologists examine entire communities or populations to uncover patterns and causes of health issues.

The scope of epidemiology is broad and encompasses a wide array of health concerns. It's not limited to communicable diseases; epidemiologists also study chronic illnesses such as heart disease and cancer, environmental health issues, occupational hazards, injuries, maternal and child health, and mental health. They work to understand who is at risk, what factors contribute to illness or health, and what interventions are most effective in improving the health of populations. The ultimate goal is to use this knowledge to promote health and reduce disease, disability, and death.

Epidemiologists are essentially the investigators of the public health world. They use scientific methods to identify the causes of diseases and to propose ways to control or prevent them. Their work can range from investigating an acute outbreak of food poisoning in a local community to conducting long-term studies on the factors that influence the development of diseases like Alzheimer's over many years. They play a critical role in informing public health policy and in designing interventions to protect and improve the health of the public.

A Look Back: Key Moments in Epidemiology's History

The roots of epidemiology can be traced back to ancient times, with figures like Hippocrates observing that environmental factors could influence disease occurrence. However, the field began to take its modern shape in the 19th century. One of the most iconic moments was Dr. John Snow's investigation of cholera outbreaks in London in the 1850s. By meticulously mapping cases and identifying a contaminated water pump as the source, he demonstrated the power of systematic investigation in controlling disease, even before the germ theory of disease was widely accepted.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw significant advancements with the rise of bacteriology and the identification of specific microbes causing diseases. This era brought about a greater understanding of infectious disease transmission and led to public health measures like sanitation and vaccination. Seminal figures during this period laid the groundwork for many of the methods still used today, focusing on disease surveillance and control.

Throughout the 20th century, epidemiology expanded its focus beyond infectious diseases to tackle chronic conditions like heart disease and cancer. Landmark studies, such as the Framingham Heart Study (which began in 1948 and is still ongoing), identified major risk factors for cardiovascular disease. The linking of smoking to lung cancer was another pivotal achievement. More recently, the field has been instrumental in addressing global health challenges, including the HIV/AIDS pandemic and emerging infectious diseases like SARS and COVID-19. These milestones underscore the evolving nature of epidemiology and its continuous adaptation to new health threats and research methodologies.

These historical examples highlight the critical thinking and problem-solving inherent in epidemiology. They demonstrate how careful observation, data collection, and analysis can lead to breakthroughs in understanding and preventing disease. Exploring these historical investigations can provide valuable insights into the core principles of the field.

For those interested in exploring the foundational concepts further, courses on the history of public health and epidemiological methods can offer a richer understanding.

The Epidemiologist's Role in Public Health and Disease Prevention

Epidemiologists are vital to the public health system, serving as the scientific backbone for disease prevention and health promotion efforts. Their primary role is to identify the distribution, patterns, and determinants (causes, risk factors) of diseases and health conditions in populations. This information is crucial for developing targeted interventions and policies aimed at reducing the incidence and impact of these conditions. For example, by identifying that a particular neighborhood has a higher rate of asthma, epidemiologists can investigate potential environmental triggers or socioeconomic factors, leading to interventions like improved air quality monitoring or better access to healthcare for residents.

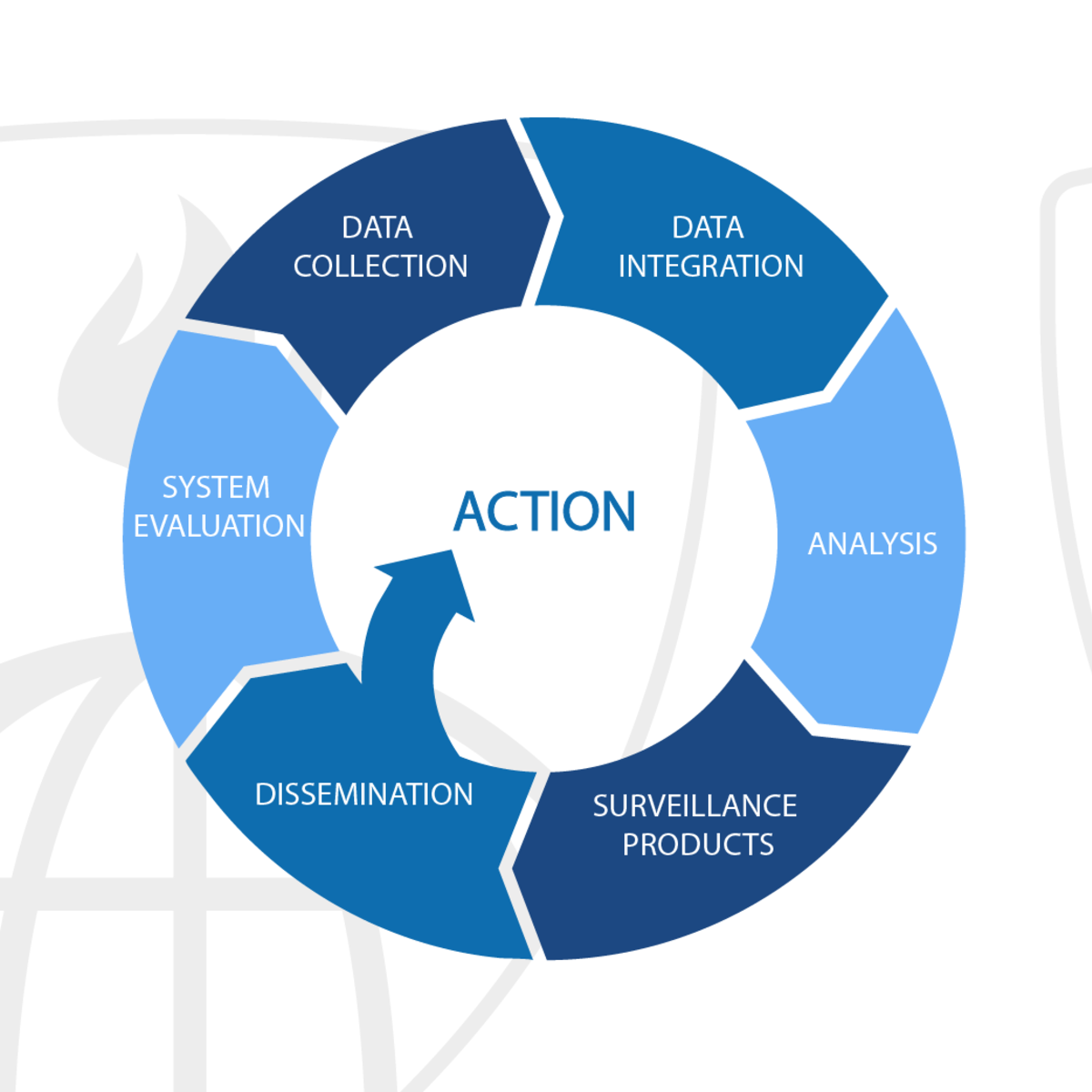

A key function of epidemiologists is disease surveillance – the ongoing, systematic collection, analysis, interpretation, and dissemination of health data. This surveillance helps public health officials monitor the health of a community, identify outbreaks or unusual patterns of disease, and assess the effectiveness of control measures. During an outbreak, such as a flu epidemic or a foodborne illness cluster, epidemiologists are on the front lines, working to identify the source, understand how it's spreading, and implement measures to contain it. They might conduct interviews, collect biological samples, and analyze data to quickly pinpoint the cause and recommend actions.

Beyond outbreak investigation, epidemiologists contribute to disease prevention by studying risk factors for chronic diseases like diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. This research can identify modifiable risk factors, such as diet, physical activity, or exposure to certain chemicals, leading to public health campaigns and policies that encourage healthier behaviors and environments. They also evaluate the effectiveness and impact of prevention programs and health services, ensuring that resources are used efficiently and that interventions are actually making a difference in community health. Their work informs everything from vaccination programs to health education initiatives.

These foundational courses provide a solid introduction to the principles and practices that epidemiologists use to safeguard public health.

Understanding the fundamental role of epidemiology in public health can be further enhanced by exploring related topics and career paths within the broader field.

Core Responsibilities of Epidemiologists

The daily work of an epidemiologist is diverse and dynamic, involving a blend of scientific investigation, data analysis, and communication. Professionals in this field are tasked with protecting public health by understanding and addressing disease patterns.

Keeping Watch: Disease Surveillance and Data Analysis

A fundamental responsibility of epidemiologists is disease surveillance. This involves systematically collecting, analyzing, and interpreting health data to monitor for outbreaks, track disease trends, and identify emerging health threats. Imagine it as the public health equivalent of an early warning system. Data sources can be varied, including reports from hospitals and clinics, laboratory results, public health surveys, and even newer sources like social media trends. Epidemiologists use this information to understand the burden of disease in a community and to spot any unusual increases or patterns that might signal an outbreak or a new public health problem.

Once data is collected, rigorous analysis is key. Epidemiologists employ statistical methods to identify patterns, calculate rates of disease, and compare these rates across different populations or time periods. They look for associations between exposures (like a contaminated food source or a particular behavior) and health outcomes. This analytical work requires a strong understanding of biostatistics and the ability to use statistical software to manage and interpret large datasets. The goal is to transform raw data into meaningful information that can guide public health action.

The findings from surveillance and data analysis are then used to inform public health interventions. For instance, if surveillance data shows a rise in flu cases in a particular region, epidemiologists might recommend increased vaccination efforts or public awareness campaigns about handwashing and staying home when sick. The continuous cycle of data collection, analysis, and action is central to effective public health practice.

These courses provide an excellent foundation in the methods used for disease surveillance and the analysis of health data, crucial skills for any aspiring epidemiologist.

For a deeper dive into the statistical techniques used in epidemiology, exploring resources on biostatistics is highly recommended.

On the Front Lines: Outbreak Investigation Techniques

When a disease outbreak occurs, epidemiologists are often the first responders from a public health perspective. Their role is to investigate the source of the outbreak, understand how it is spreading, and recommend control measures to stop it. This is where the "disease detective" analogy truly comes to life. The investigation process typically involves several key steps, starting with confirming that an outbreak is indeed occurring by comparing the number of observed cases to the expected number.

Once an outbreak is confirmed, epidemiologists work to define and identify cases, often developing a case definition that includes specific symptoms and criteria. They then collect detailed information from affected individuals through interviews and questionnaires, gathering data on their exposures, activities, and contacts. This might involve tracing contacts of infected individuals to identify others who may have been exposed and to prevent further spread. Fieldwork, such as visiting affected locations or collecting environmental samples, is often a crucial part of the investigation.

Data analysis plays a critical role in identifying patterns and potential sources. Epidemiologists might create an "epi curve" to visualize the onset of illness over time, which can provide clues about the type of exposure and the incubation period of the disease. They also use statistical methods to compare exposure histories of ill and well individuals to pinpoint likely sources of infection. The ultimate aim is to implement control measures rapidly, which could range from recalling contaminated food to recommending isolation or quarantine measures.

Understanding how to investigate and respond to outbreaks is a core competency for epidemiologists. These courses offer valuable insights into the techniques and strategies involved.

Exploring topics related to outbreak investigation can provide a more comprehensive understanding of this critical area of epidemiology.

Shaping Health: Policy Development and Communication Strategies

The work of an epidemiologist doesn't end with data analysis and investigation. A crucial aspect of their role is translating complex scientific findings into actionable recommendations for health practitioners, policymakers, and the public. This involves effectively communicating research results and their implications, which can influence the development of public health policies and programs. For instance, epidemiological studies demonstrating the link between air pollution and respiratory illnesses can provide the evidence base for stricter air quality regulations.

Epidemiologists often work with government agencies and health organizations to develop and evaluate public health policies. They might be involved in designing health education campaigns, advocating for legislative changes to improve health, or planning resource allocation for disease prevention programs. This requires not only scientific expertise but also an understanding of the policymaking process and the ability to collaborate with diverse stakeholders. Strong communication skills, both written and verbal, are essential for conveying technical information in a clear and understandable way to different audiences.

Furthermore, epidemiologists play a role in educating the public about health risks and preventive measures. During public health emergencies, such as a pandemic, they are often key sources of information, explaining the science behind the recommendations and helping to address public concerns. This requires an ability to build trust and communicate with empathy, particularly when dealing with sensitive or fear-inducing topics. The goal is to empower individuals and communities to make informed decisions about their health.

These courses highlight the importance of data in shaping policy and effective communication in public health.

Delving into topics like health policy and risk factor assessment can provide further context on how epidemiological findings are translated into public health action.

Educational Pathways

Embarking on a career in epidemiology requires a strong educational foundation. The path typically involves specific undergraduate studies followed by specialized graduate-level training. Understanding these academic requirements is the first step for aspiring epidemiologists.

Laying the Groundwork: Undergraduate Prerequisites

While there isn't one single "epidemiology" major at the undergraduate level, a bachelor's degree is the necessary first step toward a career in this field. Aspiring epidemiologists often pursue degrees in science-focused disciplines such as biology, public health, or health sciences. Strong coursework in biology, chemistry, and mathematics, particularly statistics, is highly beneficial. These subjects provide the foundational knowledge needed for understanding disease processes and the quantitative methods used in epidemiological research.

Beyond the hard sciences, courses in social sciences like sociology or anthropology can also be valuable. These disciplines offer insights into human behavior, social structures, and cultural factors that can significantly influence health patterns and the effectiveness of public health interventions. Additionally, developing strong analytical and critical thinking skills through any rigorous academic program will serve you well. Some universities may offer undergraduate courses with a public health focus, which can provide an early introduction to epidemiological concepts.

Regardless of the specific major, it's wise to seek out research opportunities, internships, or volunteer experiences in public health or healthcare settings. This practical exposure can help solidify your interest in the field, provide valuable experience for graduate school applications, and begin building a professional network. Focus on courses and experiences that build a strong scientific and analytical toolkit. Many students find that a bachelor's degree in public health provides a broad yet relevant foundation.

To supplement your undergraduate studies or to explore foundational concepts online, consider courses that cover essential scientific and statistical principles.

Exploring fundamental topics in biology and statistics can further strengthen your preparation for graduate studies in epidemiology.

Advanced Studies: Graduate Programs in Epidemiology

To work as an epidemiologist, at least a master's degree is typically required. The most common graduate degree for epidemiologists is a Master of Public Health (MPH) with a concentration in epidemiology. An MPH program provides comprehensive training in public health principles, including biostatistics, environmental health, health policy and management, and social and behavioral sciences, in addition to specialized epidemiology coursework. Some individuals may opt for a Master of Science (MS) in Epidemiology, which often has a stronger research and methods focus.

MPH and MS programs in epidemiology delve into core epidemiological methods, including study design, data collection and analysis, disease surveillance, and outbreak investigation. Students learn to critically evaluate scientific literature, design research studies, and apply statistical techniques to analyze health data. Many programs also require a practicum or internship, offering valuable hands-on experience in a public health setting. This practical component allows students to apply their classroom learning to real-world public health challenges.

For those interested in high-level research positions, particularly in academia or at federal agencies like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or the National Institutes of Health (NIH), a doctoral degree (PhD or DrPH) in epidemiology is often necessary. A PhD program typically involves more intensive research training, culminating in a dissertation based on original research. Some epidemiologists also hold medical degrees (MD or DO), often combining clinical practice with epidemiological research.

A strong foundation in epidemiological principles is essential for graduate studies. These introductory courses can provide a taste of what you'll learn in a master's program.

The following books are often considered essential reading for students and professionals in epidemiology, providing in-depth knowledge of the field.

Further exploration of core epidemiological concepts will be beneficial as you consider graduate programs.

Staying Current: Certifications and Licensure

While licensure is generally not required for epidemiologists in the same way it is for physicians or nurses, certifications can enhance professional credibility and demonstrate a commitment to the field. One prominent certification is the Certified in Public Health (CPH) credential offered by the National Board of Public Health Examiners (NBPHE). The CPH exam covers core areas of public health knowledge, including epidemiology, biostatistics, and health policy. While not always mandatory for employment, it is becoming increasingly recognized and valued by employers.

Some epidemiologists, particularly those working in specific subfields or in certain healthcare settings, may pursue other specialized certifications. For example, those focusing on infection control might seek certification from the Certification Board of Infection Control and Epidemiology (CBIC), which offers the CIC® (Certification in Infection Control) credential. Additionally, some states or specific job roles might have their own requirements or preferred qualifications, so it's important to research the specific context in which you plan to work.

Continuing Education (CE) is also a critical aspect of an epidemiologist's career. The field of public health is constantly evolving with new research findings, emerging diseases, and changing methodologies. Participating in CE activities, such as attending conferences, workshops, and online courses, helps epidemiologists stay current with the latest advancements and maintain their expertise. Many professional organizations offer CE opportunities, and some certifications require ongoing CE credits for maintenance.

Online courses are an excellent way to gain specialized knowledge and fulfill continuing education requirements. OpenCourser offers a wide array of courses in public health and epidemiology that can help professionals stay current and expand their skill sets. You can easily browse courses in Health & Medicine to find relevant options.

These courses delve into specific areas relevant to practicing epidemiologists and can contribute to continuing education.

Understanding the importance of ongoing learning and professional development is key. Exploring topics like health research and study design can further enhance an epidemiologist's expertise.

Essential Skills and Competencies

Success as an epidemiologist hinges on a unique blend of analytical prowess, critical thinking abilities, and strong interpersonal skills. Mastering these competencies is crucial for navigating the complexities of public health research and practice.

The Language of Data: Statistical Analysis and Software Proficiency

At the heart of epidemiology lies the ability to understand, interpret, and draw meaningful conclusions from data. Strong statistical analysis skills are therefore non-negotiable for an epidemiologist. This involves more than just plugging numbers into a formula; it requires a deep understanding of statistical principles, such as probability, sampling, hypothesis testing, and regression analysis. Epidemiologists must be able to choose appropriate statistical methods for different types of data and research questions, and accurately interpret the results to assess associations, identify risk factors, and evaluate interventions.

Proficiency in statistical software is also essential. Epidemiologists regularly work with large datasets, and software packages like SAS, SPSS, and R are standard tools of the trade. R, in particular, is a powerful open-source language widely used for statistical computing and graphics. The ability to manage data, perform complex analyses, and create visualizations using these software programs is a critical skill. Familiarity with database management can also be advantageous. Many epidemiologists find that skills in data science are increasingly valuable in their work.

Online courses offer excellent opportunities to develop and hone these statistical and software skills. Whether you're looking to learn the fundamentals of biostatistics or master a specific software package, there are numerous resources available. For instance, OpenCourser's platform allows you to search for courses related to Data Science and R programming to enhance your analytical capabilities.

These courses offer practical training in statistical analysis and relevant software, which are fundamental for epidemiological work.

For those looking to build a strong foundation in statistical thinking and its application, these topics are highly relevant.

Thinking Like a Detective: Critical Thinking and Problem-Solving

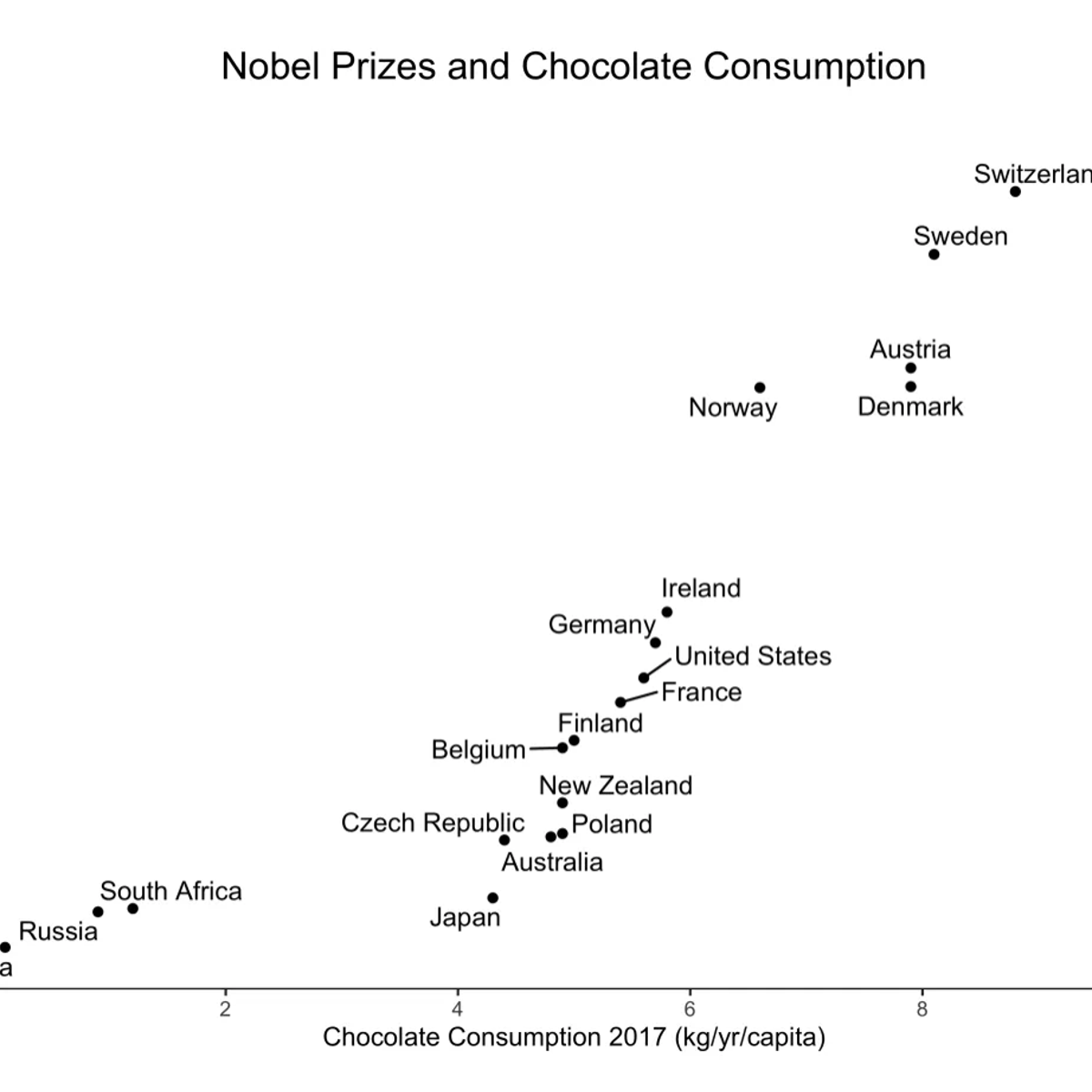

Epidemiology is fundamentally about solving puzzles – identifying the causes of disease, understanding patterns of illness, and figuring out how to intervene effectively. This requires exceptional critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Epidemiologists must be able to approach complex health issues systematically, break them down into manageable components, and develop logical and evidence-based solutions. They need to evaluate information from various sources, identify potential biases, and draw sound conclusions even when faced with incomplete or conflicting data.

When investigating an outbreak, for example, an epidemiologist must think critically about potential sources of exposure, modes of transmission, and factors that might be contributing to the spread. This involves formulating hypotheses, designing studies to test those hypotheses, and interpreting the findings in the context of existing knowledge. They must also be adept at identifying limitations in their own research and considering alternative explanations for their observations.

Problem-solving in epidemiology often involves navigating ambiguity and uncertainty. Public health challenges are rarely straightforward, and solutions often require creative and adaptive thinking. Epidemiologists must be resourceful in finding ways to collect data, overcome obstacles in investigations, and develop practical and effective interventions within real-world constraints. The ability to think on one's feet and adapt to changing circumstances is a hallmark of a successful epidemiologist.

Developing strong critical thinking and problem-solving skills is an ongoing process. Engaging with case studies and complex public health scenarios can be highly beneficial.

Further exploring topics related to research methodology and causal inference can significantly enhance an epidemiologist's problem-solving toolkit.

Working Together: Interdisciplinary Collaboration in Public Health

Public health problems are rarely solved in isolation. Addressing complex health issues effectively requires collaboration across a wide range of disciplines. Epidemiologists frequently work as part of multidisciplinary teams that may include physicians, nurses, statisticians, laboratory scientists, environmental health specialists, health educators, social workers, and policymakers. The ability to work effectively within these teams, communicate clearly with individuals from different professional backgrounds, and appreciate diverse perspectives is crucial.

For instance, during an outbreak investigation, an epidemiologist might collaborate with laboratory staff to confirm diagnoses, with clinicians to gather patient information, and with health communication specialists to develop public messaging. When developing health policies, they may work with economists to assess the cost-effectiveness of interventions or with community leaders to ensure that programs are culturally appropriate and meet the needs of the target population.

Strong interpersonal and communication skills are vital for successful interdisciplinary collaboration. This includes the ability to listen actively, articulate ideas clearly, negotiate effectively, and build consensus. Epidemiologists must be able to explain complex technical information to non-technical audiences and to understand and integrate insights from other fields into their own work. The success of public health initiatives often depends on the strength of these collaborative relationships.

These courses emphasize the collaborative nature of public health and the importance of working with diverse teams and communities.

Understanding the broader context of public health and global health can highlight the importance of interdisciplinary teamwork.

Career Progression and Specializations

A career in epidemiology offers diverse pathways for growth and specialization. From entry-level positions to senior leadership roles, and from focusing on infectious diseases to chronic conditions, epidemiologists can tailor their careers to their interests and expertise. The field provides ample opportunities for continuous learning and making a significant impact on public health.

From Entry Point to Expertise: Navigating Career Levels

Entry-level positions in epidemiology, typically requiring a master's degree (MPH or MS), often involve roles in state or local health departments, research institutions, or hospitals. In these roles, individuals might be involved in data collection and analysis, assisting with outbreak investigations, conducting literature reviews, or contributing to public health program implementation. These early career experiences are crucial for building foundational skills and gaining practical knowledge.

With experience and potentially further education (such as a PhD or DrPH), epidemiologists can advance to more senior positions. This might include leading research projects, managing surveillance systems, overseeing public health programs, or taking on supervisory responsibilities for junior staff. Senior epidemiologists often have more autonomy in designing studies, securing research funding through grant proposals, and influencing public health policy. They may also specialize in a particular area of epidemiology, becoming recognized experts in their chosen field.

Leadership opportunities are available in various settings, including government agencies (like the CDC or NIH), academic institutions, international health organizations (like the World Health Organization), and private sector companies such as pharmaceutical firms or healthcare consulting. These roles often involve strategic planning, program direction, and mentoring other public health professionals. Career progression often depends on a combination of experience, advanced education, research productivity, and leadership skills.

Understanding the trajectory from foundational knowledge to advanced application is key. These courses cover a range of topics that can support career development at various stages.

Exploring advanced topics within epidemiology and public health can pave the way for specialized and leadership roles.

Finding Your Niche: Specializations in Epidemiology

Epidemiology is a broad field, and many professionals choose to specialize in a particular area of public health. One major area of specialization is infectious disease epidemiology. These epidemiologists focus on tracking, investigating, and preventing the spread of communicable diseases, ranging from common illnesses like influenza to emerging threats like COVID-19 or Ebola. Their work often involves outbreak investigation, vaccine effectiveness studies, and developing strategies to control transmission in communities and healthcare settings. Many find this work exciting due to its fast-paced nature and direct impact on controlling acute health threats.

Another significant specialization is chronic disease epidemiology. This area focuses on understanding the causes, distribution, and prevention of long-term health conditions such as heart disease, cancer, diabetes, and respiratory diseases. Chronic disease epidemiologists often conduct large-scale population studies to identify risk factors (like diet, lifestyle, or environmental exposures) and develop interventions to reduce the burden of these conditions. Their work is critical in addressing some of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality globally.

Beyond these, there are many other specializations, including environmental epidemiology (studying the impact of environmental factors on health), maternal and child health epidemiology, injury epidemiology, psychiatric epidemiology, and pharmacoepidemiology (studying the use and effects of drugs in populations). Some epidemiologists also specialize in methodological areas, such as biostatistics or spatial epidemiology. The choice of specialization often depends on individual interests, career goals, and the specific public health challenges one wishes to address.

These courses offer insights into various epidemiological specializations, helping individuals explore areas of potential focus.

For those interested in specific disease areas, these books provide comprehensive overviews.

Delving into specific disease topics can help aspiring epidemiologists identify their areas of passion.

Leading the Way: Leadership in Public Health Organizations

Experienced epidemiologists with strong leadership qualities often move into roles where they guide public health initiatives and organizations. These leadership positions can be found in a variety of settings, including government health agencies at the local, state, and federal levels, academic institutions, non-profit organizations, and international health bodies. Leaders in epidemiology are responsible for setting strategic directions, managing teams of researchers and public health professionals, securing funding, and representing their organizations to the public and policymakers.

Effective leadership in public health requires more than just scientific expertise. It also demands strong communication, interpersonal, and management skills. Leaders must be able to inspire and motivate their teams, build collaborations with other organizations, navigate complex political and social environments, and advocate effectively for public health priorities. They often play a key role in translating research findings into impactful public health programs and policies that can improve the health of entire populations.

Many leadership roles require advanced degrees, such as a DrPH (Doctor of Public Health) or a PhD, along with significant experience in the field. Mentorship and professional development are also important for aspiring leaders. Gaining experience in project management, grant writing, and policy development can pave the way for leadership opportunities. The ability to think strategically and to anticipate future public health challenges is also a hallmark of effective leadership in this dynamic field.

These courses can help develop the skills necessary for leadership roles in public health, focusing on policy, program management, and strategic thinking.

Exploring topics related to health systems and policy can provide a broader understanding of the landscape in which public health leaders operate.

Challenges in Modern Epidemiology

The field of epidemiology, while offering immense rewards in protecting public health, is not without its significant challenges. Modern epidemiologists grapple with a complex array of issues, from the ever-present threat of new diseases to ethical dilemmas and resource constraints.

The Ever-Present Threat: Emerging Infectious Diseases and Pandemics

One of the most significant and persistent challenges in epidemiology is the emergence and re-emergence of infectious diseases. Factors such as globalization, urbanization, climate change, and ecological disruption contribute to the increased risk of pathogens jumping from animals to humans (zoonotic diseases) or spreading rapidly across borders. The COVID-19 pandemic served as a stark reminder of the world's vulnerability to novel viruses and the critical role epidemiologists play in understanding and combating such threats.

Responding to pandemics and large-scale epidemics requires rapid mobilization of resources, effective surveillance systems, quick development and deployment of diagnostic tests, vaccines, and treatments, and clear public health communication. Epidemiologists are central to all these efforts, from tracking the spread of the disease and identifying risk factors to evaluating the effectiveness of control measures. However, they often face challenges such as incomplete data in the early stages of an outbreak, public mistrust or misinformation, and the logistical hurdles of implementing interventions on a massive scale.

Preparing for future pandemics involves strengthening global health security, investing in research on potential pandemic pathogens, and improving early warning systems. This also includes addressing the underlying drivers of disease emergence. The work in this area is ongoing and requires international collaboration and sustained commitment. Epidemiologists are at the forefront of these efforts, working to build resilience against future health crises.

Understanding the dynamics of infectious diseases and pandemic preparedness is crucial. These courses offer valuable knowledge in this critical area.

Books on past and potential future pandemics offer deep insights into the challenges epidemiologists face.

Exploring topics like pandemics and emerging diseases can provide a comprehensive understanding of this complex challenge.

Navigating the Gray Areas: Data Privacy and Ethical Dilemmas

Epidemiological research and public health surveillance rely heavily on the collection and analysis of personal health information. While this data is essential for understanding disease patterns and protecting public health, its use raises significant data privacy and ethical concerns. Epidemiologists must navigate a complex landscape of regulations and ethical guidelines to ensure that individuals' privacy is protected while still enabling vital public health work.

The increasing use of big data, electronic health records, and digital technologies in epidemiology further amplifies these concerns. While these tools offer powerful new ways to track and analyze health trends, they also create new risks for data breaches and misuse of sensitive information. Ensuring data security, obtaining informed consent, and maintaining confidentiality are paramount. Ethical dilemmas can also arise when balancing individual liberties with public health measures, such as during quarantine or mandatory vaccination programs.

Epidemiologists must be well-versed in ethical principles and data privacy laws, such as HIPAA in the United States. They need to employ methods to de-identify data where possible and to ensure that research protocols are reviewed and approved by institutional review boards (IRBs) or ethics committees. Transparency with the public about how data is being used and protected is also crucial for maintaining trust. Addressing these ethical challenges thoughtfully is essential for the responsible practice of epidemiology.

Courses that touch upon research ethics and data governance are valuable for understanding these complex issues.

Understanding the ethical frameworks and privacy considerations in health data is becoming increasingly important.

Doing More with Less: Funding and Resource Allocation Challenges

Public health initiatives, including epidemiological research and surveillance, often face significant funding and resource allocation challenges. Securing adequate and sustained funding for public health infrastructure, research projects, and emergency preparedness can be a constant struggle. Epidemiologists, particularly those in academic or research settings, frequently need to write grant proposals to fund their work, a competitive and time-consuming process.

Budget constraints can impact the ability to conduct thorough investigations, maintain robust surveillance systems, hire and retain skilled personnel, and implement effective interventions. This is particularly true in low-resource settings, both domestically and internationally, where the public health needs may be greatest but the available resources are most limited. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the consequences of underinvestment in public health infrastructure over many years.

Epidemiologists must often be adept at prioritizing activities and making the most of limited resources. This can involve advocating for increased public health funding, demonstrating the value and impact of epidemiological work, and finding innovative and cost-effective ways to achieve public health goals. Collaboration and partnerships can also help to leverage resources and avoid duplication of effort. Addressing the challenge of resource allocation is critical for ensuring that public health systems can effectively protect and promote the health of all populations.

Understanding the economics of healthcare and public health can provide context for these funding challenges.

Exploring how public health programs are funded and managed is crucial for epidemiologists working in various settings.

Global Impact and International Opportunities

Epidemiology is inherently a global field, as diseases know no borders. The interconnectedness of the world means that health threats can spread rapidly, necessitating international cooperation and a global perspective on public health. For epidemiologists, this opens up a wide range of opportunities to contribute to health improvements worldwide.

A World Connected: Cross-Border Disease Control Efforts

In an era of frequent international travel and trade, infectious diseases can spread from one country to another with unprecedented speed. This makes cross-border disease control a critical component of global health security. Epidemiologists play a key role in monitoring disease activity globally, sharing information across borders, and coordinating responses to international outbreaks. Organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) work with member states to establish international health regulations and provide support during public health emergencies.

Effective cross-border control requires robust surveillance systems in all countries, the ability to rapidly detect and report unusual health events, and mechanisms for international collaboration and mutual assistance. Epidemiologists may be involved in developing these systems, training public health personnel in different countries, or participating in international outbreak investigation teams. The challenges are significant, including variations in healthcare infrastructure, cultural differences, and political sensitivities, but the need for a coordinated global response to health threats is undeniable.

The COVID-19 pandemic vividly illustrated the importance of international cooperation in sharing data, research findings, and resources to combat a global health crisis. Epidemiologists were central to understanding the virus's transmission, evaluating the effectiveness of different control measures in various settings, and tracking the emergence of new variants. These experiences continue to shape efforts to strengthen global preparedness for future pandemics.

These courses provide insights into global health challenges and the collaborative efforts required to address them.

Books on global health and international health organizations offer valuable context for understanding cross-border disease control efforts.

Exploring global health topics can provide a deeper understanding of the interconnectedness of health issues worldwide.

Teamwork Across Nations: Collaboration with International Health Organizations

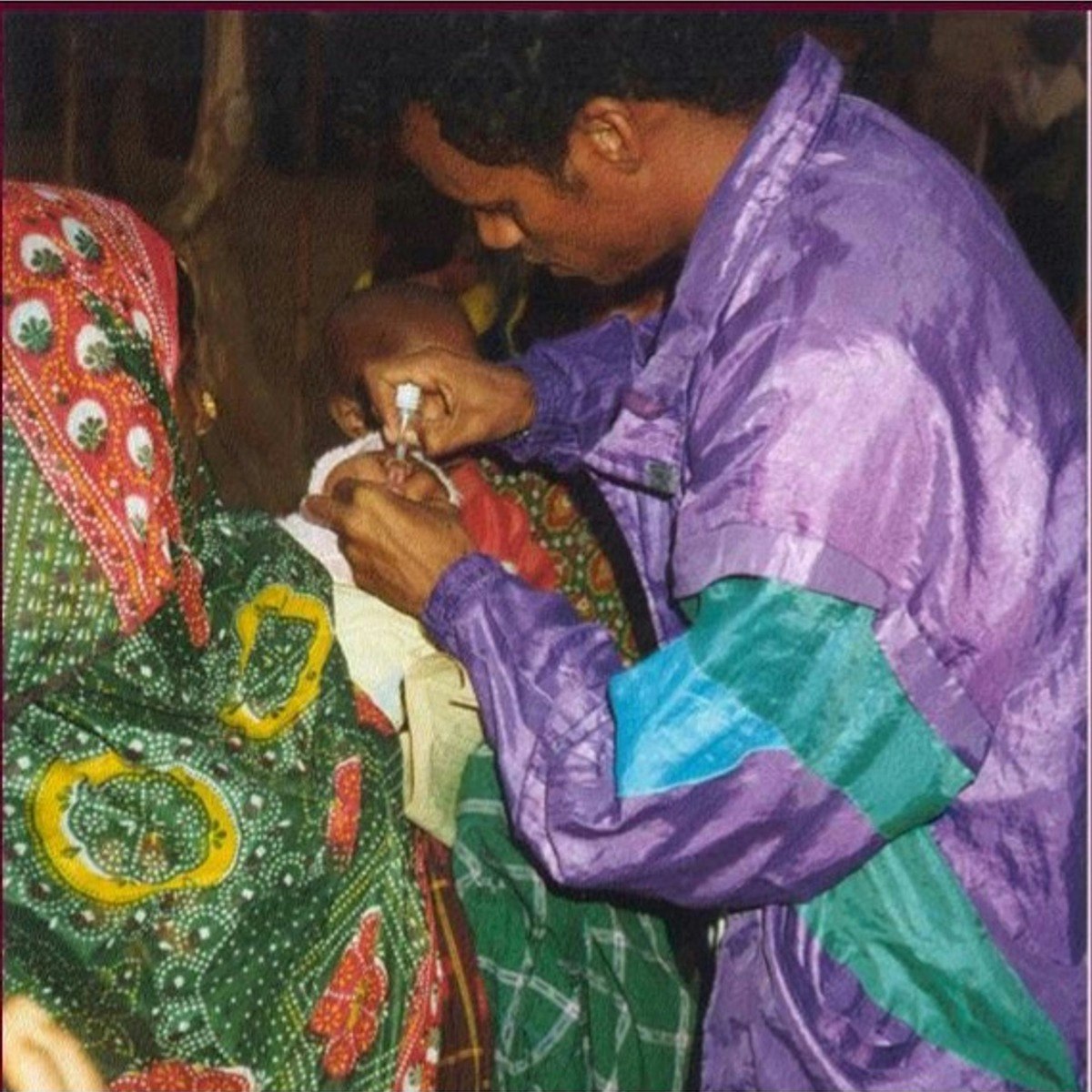

Many epidemiologists find fulfilling careers working with international health organizations dedicated to improving global health. Prominent organizations in this sphere include the World Health Organization (WHO), UNICEF, the World Bank, and numerous non-governmental organizations (NGOs) like Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) and Partners In Health. These organizations undertake a wide range of activities, from disease surveillance and outbreak response to strengthening health systems and addressing health inequities in low- and middle-income countries.

Working for an international health organization often involves travel, sometimes to remote or challenging environments, and requires adaptability and cross-cultural sensitivity. Epidemiologists in these roles might be involved in designing and implementing health programs, conducting research in diverse settings, providing technical assistance to ministries of health, or advocating for global health priorities. The work can be incredibly rewarding, offering the chance to make a direct impact on the lives of vulnerable populations.

Collaboration is a cornerstone of international health work. Epidemiologists frequently partner with local health workers, government officials, community leaders, and other international experts. Building trust and fostering effective working relationships across different cultures and contexts are essential skills for success in this arena. Many international health initiatives rely on interdisciplinary teams to address the multifaceted determinants of health.

These courses provide valuable insights into the workings of global health initiatives and the importance of international collaboration.

Understanding the landscape of international health organizations is key for those interested in global careers.

Bridging Divides: Cultural Competency in Global Settings

Cultural competency is a critical skill for epidemiologists working in global health settings. Health beliefs, practices, and social norms vary significantly across cultures, and these factors can profoundly influence disease patterns, health-seeking behaviors, and the acceptability and effectiveness of public health interventions. An epidemiologist who is not attuned to these cultural nuances may struggle to collect accurate data, design appropriate interventions, or build the trust necessary for successful collaboration with local communities.

Developing cultural competency involves more than just learning about different customs; it requires an attitude of humility, respect, and a willingness to learn from others. It means recognizing one's own cultural biases and assumptions and being open to understanding health and illness from different perspectives. This might involve working closely with local interpreters and cultural brokers, engaging community leaders in the design and implementation of health programs, and adapting communication strategies to be culturally sensitive and appropriate.

For example, understanding local beliefs about the causes of illness can inform how health messages are framed. Recognizing traditional healing practices can help in integrating public health interventions with existing healthcare systems. Building rapport and trust with communities is essential for gaining cooperation in research studies and ensuring the success of public health programs. Cultural competency is not just a "soft skill"; it is a fundamental component of effective and ethical epidemiological practice in global settings.

These courses touch upon the social and cultural aspects of health, which are crucial for working effectively in diverse global settings.

Understanding the social determinants of health is crucial for culturally competent epidemiological practice.

Technological Advancements in Epidemiology

Technology is rapidly transforming the field of epidemiology, providing new tools and methods for collecting, analyzing, and interpreting health data. From the power of big data and artificial intelligence to the precision of geographic information systems, these advancements are enhancing our ability to understand and respond to public health challenges.

The Power of Information: Big Data and AI in Disease Modeling

The era of big data has arrived in epidemiology, bringing with it unprecedented opportunities to analyze vast and diverse datasets. This includes electronic health records, genomic data, social media feeds, wearable sensor data, and environmental monitoring information. Epidemiologists are increasingly using these large datasets to identify subtle patterns, predict disease outbreaks with greater accuracy, and understand the complex interplay of factors that influence health.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning are playing a crucial role in harnessing the power of big data. AI algorithms can analyze complex datasets much faster and often with greater precision than traditional statistical methods. They are being used for tasks such as early outbreak detection, forecasting disease trends, identifying populations at high risk, and even accelerating drug discovery and development. For example, AI can analyze news reports or social media posts in real-time to detect early signals of an emerging epidemic.

While the potential of big data and AI in epidemiology is immense, there are also challenges to address. These include issues of data quality and bias, the need for specialized analytical skills, ethical concerns around data privacy and algorithmic fairness, and the "black box" nature of some AI models, which can make it difficult to understand how they arrive at their conclusions. However, the ongoing development and refinement of these technologies promise to significantly enhance the toolkit available to epidemiologists.

These courses explore the application of data science, machine learning, and AI in health contexts, reflecting the cutting edge of epidemiological research.

The integration of AI and big data is a rapidly evolving area. Understanding these technological shifts is crucial for modern epidemiologists.

Mapping Health: Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Applications

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) have become invaluable tools in epidemiology and public health. GIS technology allows epidemiologists to visualize and analyze health data in a spatial context, by mapping the distribution of diseases, identifying geographical hotspots or clusters of illness, and exploring the relationship between health outcomes and environmental or social factors. This spatial perspective can provide crucial insights that might be missed with traditional data analysis alone.

GIS is used in a wide range of applications, including tracking the spread of infectious disease outbreaks, identifying areas with limited access to healthcare services, assessing exposure to environmental hazards like air or water pollution, and planning the optimal location of health facilities. For example, by mapping cases of a foodborne illness and overlaying data on restaurant locations or food supply chains, GIS can help pinpoint the source of an outbreak. During the COVID-19 pandemic, GIS was widely used to map infection rates, track hospital capacity, and identify vulnerable populations.

The ability to integrate diverse datasets – such as demographic data, environmental data, healthcare infrastructure data, and disease surveillance data – within a GIS framework makes it a powerful tool for understanding the complex determinants of health. As GIS technology becomes more accessible and user-friendly, its applications in public health are continually expanding, enabling more targeted and effective interventions. You can explore GIS applications further through GIS public health resources.

This course introduces the diverse applications of GIS across various industries, highlighting its relevance to public health and epidemiology.

Understanding how spatial data is collected, analyzed, and visualized is a valuable skill for epidemiologists.

The Digital Shift: Telehealth and Digital Surveillance Tools

The rise of digital technologies is profoundly impacting how public health surveillance is conducted and how healthcare services, including those related to epidemiological investigations, are delivered. Digital surveillance tools encompass a wide range of technologies, from automated reporting systems for infectious diseases to the use of mobile phone data, social media analytics, and wearable sensors to monitor health trends and detect outbreaks in near real-time. These tools can provide more timely and granular data than traditional surveillance methods, enabling faster public health responses.

Telehealth, or the provision of healthcare services remotely using telecommunications technology, has also gained prominence, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. While primarily a healthcare delivery model, telehealth can intersect with epidemiology in various ways. For instance, telehealth platforms can facilitate remote data collection for research studies, support contact tracing efforts by enabling virtual interviews, and help monitor individuals in quarantine or isolation. It can also expand access to public health information and counseling.

However, the increasing reliance on digital tools also brings challenges. Ensuring data privacy and security, addressing the digital divide (inequitable access to technology), validating the accuracy of data from non-traditional sources, and integrating digital data with existing public health systems are all important considerations. Despite these hurdles, the trend towards greater use of digital technologies in epidemiology is clear, offering exciting possibilities for enhancing public health practice.

These courses explore the intersection of digital technology, data, and healthcare, which are increasingly relevant to modern epidemiology.

The evolving landscape of digital health tools presents both opportunities and challenges for epidemiologists.

Career Transitioning into Epidemiology

Making a career change into epidemiology is a feasible and often rewarding path for individuals with backgrounds in related fields. Leveraging existing skills and acquiring specialized knowledge are key components of a successful transition. This section offers guidance and encouragement for those considering this professional pivot.

From a Related Field: Transferable Skills

Professionals from various scientific and healthcare backgrounds often possess a wealth of transferable skills that are highly valuable in epidemiology. For example, individuals in nursing, medicine, biology, laboratory sciences, statistics, or even social work may find that their existing expertise provides a strong foundation for a career in epidemiology. Skills such as analytical thinking, problem-solving, data interpretation, research methodology, and communication are all critical in epidemiology and are often developed in these related professions.

Nurses and physicians, for instance, have a deep understanding of disease processes, patient care, and health systems, which can be invaluable in clinical epidemiology or outbreak investigations. Biologists and laboratory scientists bring expertise in pathogens, molecular techniques, and diagnostic testing. Statisticians and data analysts already possess the quantitative skills that are central to epidemiological analysis. Even those from less obvious fields, like urban planning or environmental science, might have relevant skills in spatial analysis or understanding environmental determinants of health.

The key is to identify how your current skills and experiences align with the core competencies of an epidemiologist and to highlight these connections. Recognizing the value of your existing skillset can be a significant confidence booster as you embark on this new career path. It’s not always about starting from scratch, but rather about building upon a solid existing foundation with specialized epidemiological training.

If you are considering a career change, reflecting on your current skillset is a great first step. OpenCourser's Career Development section might offer resources to help with this type of self-assessment and planning.

These courses can help bridge knowledge gaps and build upon existing skills for those transitioning into epidemiology.

Bridging the Gap: Retraining and Educational Options

For individuals transitioning into epidemiology from another field, further education is typically necessary to acquire specialized knowledge and credentials. As mentioned earlier, a Master of Public Health (MPH) with a concentration in epidemiology or a Master of Science (MS) in Epidemiology is generally the standard entry-level requirement. These programs provide rigorous training in epidemiological methods, biostatistics, and other core public health disciplines.

Fortunately, many universities offer flexible MPH and MS programs, including online and part-time options, which can be suitable for working professionals looking to make a career change. Some institutions may also offer "bridge" programs or post-baccalaureate certificates designed to help individuals with non-science backgrounds gain the prerequisite knowledge for graduate study in public health. It's important to research different programs to find one that aligns with your career goals and learning style. OpenCourser is an excellent resource for finding and comparing epidemiology master's programs and related online courses.

When selecting a program, consider factors such as curriculum, faculty expertise, research opportunities, and practicum placements. The practicum or internship component of a graduate program is particularly valuable for career changers, as it provides hands-on experience and allows you to apply your new skills in a real-world setting. This experience can also be crucial for building a professional network in the epidemiology field.

These courses are excellent starting points for anyone looking to build foundational knowledge in epidemiology as part of a career transition.

For those needing to strengthen their quantitative skills, a foundational book in statistics can be immensely helpful.

Building Connections: Networking and Mentorship Strategies

Networking and mentorship are invaluable assets for anyone transitioning into a new career, and epidemiology is no exception. Building connections with established professionals in the field can provide insights into career paths, job opportunities, and the day-to-day realities of working as an epidemiologist. Professional organizations, such as the American Public Health Association (APHA) or the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE), offer excellent networking opportunities through conferences, workshops, and online forums. APHA and CSTE are great resources to explore.

Seeking out a mentor who is an experienced epidemiologist can provide personalized guidance and support throughout your career transition. A mentor can offer advice on educational choices, help you identify relevant job opportunities, provide feedback on your resume or cover letter, and introduce you to other professionals in their network. Many universities and professional organizations have formal or informal mentorship programs. Don't hesitate to reach out to alumni from your graduate program or professionals whose work you admire.

Informational interviews are another effective networking strategy. This involves reaching out to epidemiologists working in areas or organizations that interest you and requesting a brief conversation to learn more about their work and career path. Most professionals are willing to share their experiences and offer advice to those who are genuinely interested in the field. These conversations can provide valuable insights and potentially lead to future opportunities. Remember that building a strong professional network takes time and effort, but the connections you make can be incredibly beneficial in the long run.

Engaging with the broader public health community through courses and professional development can also aid in networking.

Consider exploring related career paths to broaden your understanding of the public health landscape.

Frequently Asked Questions (Career Focus)

This section addresses some common questions that individuals exploring a career in epidemiology often have. The answers aim to provide quick insights to help with career decision-making.

Where Do Epidemiologists Work? Exploring Industries and Settings

Epidemiologists work in a diverse range of settings and industries. A significant number are employed by government agencies at the state and local levels, working in health departments to monitor community health, investigate outbreaks, and implement public health programs. Federal agencies, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), also employ many epidemiologists in research and public health practice roles. These roles often involve national-level surveillance, research on diseases of public health importance, and providing guidance on health policy.

Hospitals and other healthcare facilities also hire epidemiologists, often in roles focused on infection control and prevention (sometimes called hospital epidemiologists or infection control practitioners). Academic institutions, including universities and colleges, are major employers of epidemiologists who conduct research and teach. In these settings, epidemiologists often lead research studies, publish their findings, and train the next generation of public health professionals.

The private sector also offers opportunities for epidemiologists. Pharmaceutical companies employ epidemiologists for drug development research, post-marketing surveillance of drug safety, and outcomes research. Health insurance companies may hire epidemiologists to analyze health trends in their covered populations and develop wellness programs. Non-profit organizations and global health agencies also employ epidemiologists to work on a variety of public health issues, both domestically and internationally.

These courses provide insights into the various contexts where public health professionals, including epidemiologists, contribute their expertise.

Understanding the different sectors where epidemiologists work can help tailor your job search and career planning.

Is a PhD Necessary for Advanced Roles in Epidemiology?

While a master's degree (typically an MPH or MS in Epidemiology) is the standard entry-level requirement for most epidemiologist positions, a PhD or other doctoral degree (like a DrPH) is often necessary or highly advantageous for certain advanced roles. This is particularly true for positions that involve leading independent research projects, such as principal investigator roles in academia or at major research institutions like the NIH. A PhD program provides in-depth training in research methodology, advanced statistical analysis, and the development of original research through a dissertation.

Many senior leadership positions in academic departments, research centers, and some government agencies also prefer or require a doctoral degree. For those aspiring to become university professors and mentor graduate students, a PhD is generally essential. However, it's important to note that many highly impactful and senior roles in applied epidemiology, particularly in state and local health departments or in certain non-profit organizations, can be achieved with a master's degree and significant experience.

The decision to pursue a PhD should be based on your specific career goals. If your passion lies in conducting high-level, independent research, seeking tenure-track academic positions, or leading major research programs, then a PhD is likely a worthwhile investment. If your primary interest is in applied public health practice, program management, or policy development, a master's degree coupled with strong experience and potentially specialized certifications may be sufficient for a fulfilling and advanced career.

These courses delve into research methodologies and advanced analytical techniques often explored in doctoral programs.

Understanding the nuances of advanced research and statistical modeling can help you decide if a PhD aligns with your career aspirations.

Epidemiology vs. Public Health: What's the Difference?

Epidemiology and public health are closely related, but they are not interchangeable terms. Public health is a broad, multidisciplinary field focused on protecting and improving the health of populations. It encompasses a wide range of activities, including health education, policy development, environmental health, health administration, and, importantly, epidemiology. Think of public health as the overarching umbrella, and epidemiology as one of the core scientific disciplines that falls underneath it.

Epidemiology is often described as the basic science of public health. It provides the evidence base for public health action by studying the distribution and determinants of health and disease in populations. Epidemiologists use scientific methods to conduct research, investigate outbreaks, and analyze health data. The findings from epidemiological studies inform the development of public health interventions, programs, and policies.

So, while all epidemiologists are public health professionals, not all public health professionals are epidemiologists. A public health professional might work in health promotion, developing campaigns to encourage healthy eating, or in health policy, advocating for laws that improve access to healthcare. An epidemiologist, on the other hand, would be the one conducting studies to determine which dietary factors are linked to obesity or evaluating the impact of a new healthcare law on health outcomes. Both roles are essential for a functioning public health system, but their specific focus and methodologies differ.

These foundational courses explore the breadth of public health and the specific role of epidemiology within it.

Exploring the core concepts of public health provides a better understanding of epidemiology's context.

Show Me the Data: Salary Expectations and Job Outlook

The job outlook for epidemiologists is quite positive. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), employment of epidemiologists is projected to grow 19 percent from 2023 to 2033, which is much faster than the average for all occupations. This projected growth is expected to result in about 800 job openings for epidemiologists each year, on average, over the decade. This demand is driven by factors such as the ongoing need to respond to public health threats, the increasing use of data in healthcare, and a greater emphasis on preventative health.

In terms of salary, the median annual wage for epidemiologists was $83,980 in May 2024, according to the BLS. However, salaries can vary significantly based on factors such as geographic location, level of experience, education (master's vs. doctoral degree), and the type of employer. For example, epidemiologists working in scientific research and development services or for private hospitals often earn higher median salaries than those in state or local government. The lowest 10 percent of epidemiologists earned less than $56,950, while the highest 10 percent earned more than $134,860 in May 2024. Another source, Salary.com, reports an average annual salary of $93,055 as of May 2025, with a typical range between $80,777 and $101,570. ZipRecruiter shows a similar average annual pay of $85,222 as of May 2025.

Experience level also plays a role, with entry-level positions generally earning less than senior-level roles requiring more experience and expertise. For instance, an entry-level epidemiologist with less than a year of experience might earn around $87,557, while those with over 8 years of experience could earn an average of $96,232 or more. States with higher costs of living and greater demand for epidemiologists, such as Massachusetts and Washington, tend to offer higher average salaries. The increasing recognition of the importance of epidemiological work, particularly in the wake of global health events, contributes to a favorable job market for qualified professionals.

These courses can help aspiring epidemiologists develop the skills that are in demand in the job market.

Understanding market trends and salary expectations is an important part of career planning. Reputable sources like the Occupational Outlook Handbook from the BLS provide valuable data.

Working From Anywhere? Remote Work Opportunities

The nature of epidemiological work often involves a combination of data analysis, report writing, collaboration, and sometimes fieldwork. While some tasks, particularly data analysis and writing, can be performed remotely, other aspects, like outbreak investigations that require on-site presence or laboratory work, inherently cannot. The availability of remote work opportunities for epidemiologists can vary significantly depending on the specific role, employer, and the nature of the projects involved.

In recent years, particularly accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a general trend towards increased acceptance of remote work in many fields, including some areas of public health. For epidemiologists whose roles are primarily research-focused and involve computer-based data analysis and report generation, remote or hybrid work arrangements may be more feasible. Positions in academia or with some consulting firms might offer more flexibility in this regard.

However, applied epidemiology roles, especially those in state and local health departments that involve direct community engagement, emergency response, or hands-on investigation, are less likely to be fully remote. Some positions may offer a hybrid model, combining remote work with occasional on-site requirements. It's important for job seekers to carefully review job descriptions and inquire about remote work policies during the application and interview process. The feasibility of remote work will continue to evolve with technological advancements and changing workplace norms.

Developing strong skills in data analysis and using collaborative online tools can enhance one's suitability for roles that may offer remote work components.

The ability to effectively manage and analyze data is key, whether working on-site or remotely.

Lab Coat or Laptop? Balancing Fieldwork and Desk-Based Research

The balance between fieldwork and desk-based research for an epidemiologist can vary greatly depending on their specific role and area of specialization. Some epidemiologists, particularly those involved in outbreak investigations ("field epidemiologists") or certain types of community-based research, may spend a significant portion of their time in the field. This can involve traveling to affected communities, conducting interviews, collecting biological or environmental samples, and observing conditions firsthand. This type of work can be dynamic and requires adaptability and strong interpersonal skills.

Conversely, many epidemiologists, especially those in research-focused roles in academia or government agencies, spend the majority of their time engaged in desk-based research. This typically involves designing studies, analyzing large datasets using statistical software, writing research papers and grant proposals, and collaborating with other researchers. These roles require strong analytical, writing, and critical thinking skills. While they may involve less travel, the intellectual challenges and potential for discovery are significant.

It's also common for epidemiologists to have roles that involve a mix of both fieldwork and desk-based research. For example, an epidemiologist working for a state health department might spend time in the office analyzing surveillance data but also be deployed to investigate local outbreaks when they occur. The specific balance often depends on the priorities of the employing organization and the nature of the public health issues being addressed. Aspiring epidemiologists should consider what type of work environment and activities they find most engaging when exploring different career paths within the field.

These courses offer insights into both the analytical and practical aspects of epidemiology, reflecting the diverse nature of the work.

Whether in the field or at a desk, the core of an epidemiologist's work is to understand and improve population health.

Embarking on Your Epidemiological Journey

A career in epidemiology offers a unique opportunity to blend scientific inquiry with a profound commitment to public health. It is a field that demands rigor, critical thinking, and a passion for solving complex health puzzles. While the path requires significant education and continuous learning, the potential to make a tangible difference in the well-being of communities is immense. Whether you are drawn to the front lines of outbreak investigations, the intricate analysis of large datasets, or the development of health policies that shape societies, epidemiology provides a challenging and deeply rewarding career. As you consider this path, remember that the journey is one of constant discovery and contribution to a healthier world.