Patient Advocate

A Career Guide to Patient Advocacy

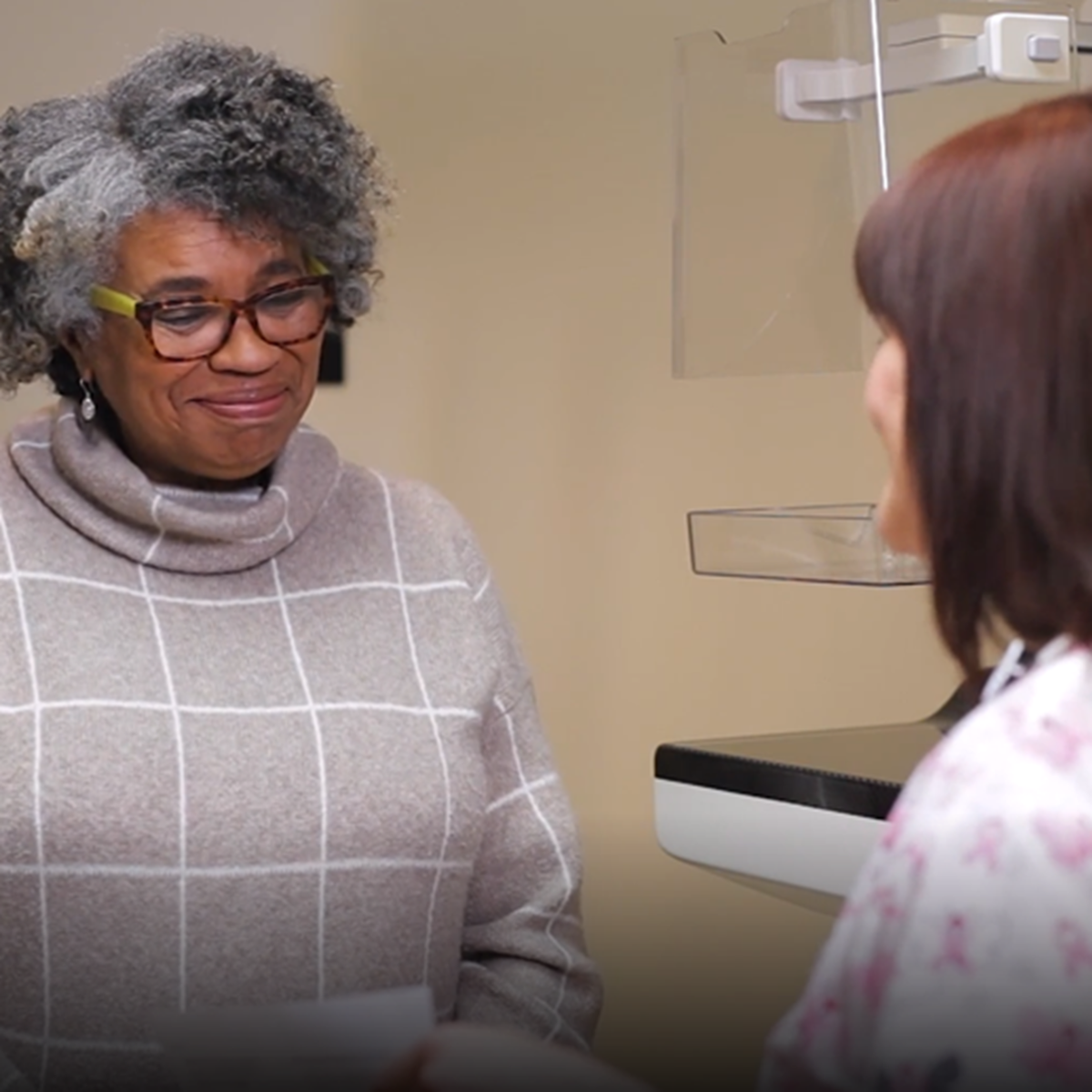

Navigating the complexities of the healthcare system can be overwhelming for patients and their families, especially during times of illness or vulnerability. A Patient Advocate steps into this challenging space, serving as a guide, supporter, and voice for individuals needing assistance. They work to ensure patients understand their rights, receive appropriate care, manage logistical hurdles like insurance and billing, and make informed decisions aligned with their values and preferences.

Working as a Patient Advocate can be deeply rewarding. You have the opportunity to directly impact individuals' lives, helping them through difficult health journeys. This role involves critical thinking to solve complex problems, strong communication to bridge gaps between patients and providers, and profound empathy to connect with people on a human level. It's a career that combines analytical skills with a deep sense of purpose.

Introduction to Patient Advocacy

What is a Patient Advocate?

A Patient Advocate is a professional who supports individuals navigating the healthcare system. Their primary goal is to empower patients by providing information, facilitating communication, and helping resolve issues related to care, insurance, billing, and access. They act as a liaison between patients, families, healthcare providers, and insurers.

Advocates ensure patients' voices are heard and their rights respected. They might help someone understand a diagnosis, explore treatment options, decipher complex medical bills, appeal an insurance denial, or arrange for necessary support services. The focus is always on the patient's needs and well-being.

This role requires a unique blend of compassion, communication prowess, problem-solving skills, and knowledge of the healthcare landscape. Advocates must be persistent, resourceful, and ethically grounded to effectively represent their clients' interests.

The Evolution of Patient Advocacy

The concept of patient advocacy emerged alongside the patient rights movement, gaining momentum in the latter half of the 20th century. As healthcare became more complex and institutionalized, the need for individuals dedicated to representing patient interests became increasingly apparent. Early advocates often came from nursing or social work backgrounds.

Initially informal, the role has become more professionalized over time. The rise of consumerism in healthcare, coupled with increasing system complexity (insurance intricacies, specialized treatments), solidified the need for dedicated advocates. Organizations dedicated to advocacy and professional certification bodies have emerged, establishing standards and credibility.

Today, patient advocacy is recognized as a distinct field within healthcare, responding to systemic challenges and empowering patients to be active participants in their care. The focus has expanded from solely resolving problems to proactively supporting patient engagement and informed decision-making throughout their healthcare journey.

Who Do Patient Advocates Serve?

Patient Advocates serve a diverse range of individuals facing various healthcare challenges. A significant portion of their work involves assisting patients with chronic or complex conditions who require ongoing, coordinated care and navigation through multiple specialists and treatments.

The elderly are another key population, often needing help managing multiple health issues, understanding Medicare/Medicaid, arranging home care, or transitioning to long-term care facilities. Advocates ensure their specific needs and preferences are addressed, safeguarding them against potential vulnerabilities.

Advocates also support patients facing sudden critical illnesses, navigating difficult diagnoses like cancer, dealing with medical errors, or struggling with significant billing or insurance disputes. Essentially, anyone feeling lost, overwhelmed, or unable to effectively communicate within the healthcare system can benefit from an advocate's help.

These courses provide insight into specific patient populations and conditions advocates might encounter.

Distinguishing Patient Advocates from Similar Roles

While Patient Advocates share the goal of helping patients, their role differs from other healthcare professionals like social workers, case managers, or nurses. Social workers often focus on psychosocial needs, connecting patients with community resources, counseling, and support for social determinants of health.

Case managers, frequently employed by hospitals or insurers, primarily focus on coordinating care for efficiency and cost-effectiveness, managing transitions, and ensuring adherence to treatment plans within the framework of the payer or facility.

Nurses provide direct clinical care, administer treatments, monitor patient conditions, and educate patients about their health. While nurses certainly advocate for their patients daily, a dedicated Patient Advocate's scope is broader, encompassing system navigation, rights protection, and communication facilitation across the entire care continuum, often independent of a specific facility or insurer.

Roles and Responsibilities of a Patient Advocate

Core Duties and Functions

The day-to-day work of a Patient Advocate involves a variety of tasks centered on patient support. A primary function is care coordination: helping patients schedule appointments, manage communication between different specialists, and ensure smooth transitions between care settings (e.g., hospital to home).

Navigating insurance and billing is another critical area. Advocates help patients understand their coverage, resolve billing errors, appeal denied claims, and find financial assistance programs. They act as intermediaries with insurance companies and hospital billing departments.

Providing emotional support and facilitating communication are also key. Advocates help patients articulate their concerns and questions to providers, ensure they understand complex medical information, and assist in making informed decisions that align with their values. They empower patients to be active participants in their care.

Common Work Environments

Patient Advocates work in various settings across the healthcare landscape. Many are employed by hospitals and health systems, often within patient relations or patient experience departments, helping patients navigate services within that specific system.

Non-profit organizations focused on specific diseases (e.g., cancer societies) or populations (e.g., seniors) frequently employ advocates to provide specialized support and resource connection. Government agencies, particularly those serving veterans or specific community health programs, may also utilize advocates.

A growing number of Patient Advocates operate in private practice, working directly for patients and families on a fee-for-service basis. Insurance companies sometimes employ advocates or care managers with similar functions to guide members through complex care needs, although their primary allegiance may be to the insurer. The setting often influences the specific focus and scope of the advocate's role.

These courses provide insights into healthcare delivery systems and the environments advocates navigate.

Legal and Ethical Boundaries

Patient advocacy operates within important legal and ethical frameworks. A fundamental principle is confidentiality, guided by laws like the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in the United States. Advocates must rigorously protect patient privacy and sensitive health information.

Advocates must clearly understand the scope of their practice. They do not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Their role is to facilitate understanding and decision-making, not to direct clinical care. Maintaining this boundary is crucial to avoid legal liability and ensure patient safety.

Ethical considerations include avoiding conflicts of interest, ensuring patient autonomy in decision-making (even when disagreeing with the patient's choice), acting with integrity, and accurately representing their qualifications and services. Adherence to a professional code of ethics, often provided by certifying bodies, is essential.

Understanding HIPAA and ethical conduct is vital for patient advocates.

Documentation and Case Management

Effective patient advocacy relies heavily on meticulous documentation and strong case management skills. Advocates must keep detailed records of patient interactions, communications with providers and insurers, actions taken, and progress made.

This documentation serves multiple purposes: it ensures continuity if another advocate takes over, provides evidence for appeals or complaints, helps track complex issues over time, and demonstrates the value of the advocacy services. Proficiency with case management software or systems may be required, depending on the work setting.

Strong organizational skills are paramount. Advocates often juggle multiple cases simultaneously, each with unique complexities and timelines. They need systems to track follow-ups, manage deadlines for appeals, and organize vast amounts of information related to medical records, insurance policies, and bills.

Developing case management skills is crucial for effective advocacy.

Formal Education Pathways

Relevant Undergraduate Degrees

While there isn't one single required degree to become a Patient Advocate, certain fields provide a strong foundation. Degrees in health-related areas such as Health Sciences, Public Health, Nursing, or Health Administration are common starting points. These programs offer crucial knowledge about healthcare systems, medical terminology, and health policy.

Degrees in Social Work or Psychology are also highly relevant, providing skills in communication, counseling, understanding psychosocial factors affecting health, and navigating social services. Communication Studies can equip individuals with essential skills for mediation and clear articulation.

Regardless of the specific major, coursework related to ethics, healthcare law, communication, and human services provides a valuable base for aspiring advocates. Many successful advocates also transition from direct clinical or administrative roles within healthcare.

Certification Programs

Professional certification adds credibility and demonstrates a standardized level of knowledge and competence in patient advocacy. The most recognized certification in the U.S. is the Board Certified Patient Advocate (BCPA), administered by the Patient Advocate Certification Board (PACB).

Achieving BCPA certification typically requires meeting eligibility criteria related to education and/or experience in advocacy or related fields, and passing a rigorous examination. The exam covers domains like ethics, communication, healthcare finance, medical knowledge, care coordination, and legal considerations.

While not always legally mandated for practice (unlike licensing for doctors or nurses), certification is increasingly preferred or required by employers, especially in hospital settings or established advocacy organizations. It signals a commitment to professional standards and ethical practice.

These books cover essential knowledge areas relevant to certification and practice.

Clinical Experience Requirements

While not universally required, prior experience in a clinical or healthcare setting is often highly beneficial, and sometimes mandatory, for Patient Advocate roles, particularly those within hospitals or complex health systems. Experience as a nurse, social worker, case manager, or even in medical billing or administration provides invaluable context.

This background helps advocates understand clinical workflows, medical terminology, provider perspectives, and the practical challenges patients face within the system. It builds credibility when interacting with clinical staff and provides a deeper understanding of the issues patients encounter.

For those entering the field without direct clinical experience, volunteering in healthcare settings, completing internships focused on patient services, or working in related support roles can help bridge this gap and build relevant skills and understanding.

Graduate-Level Specializations

While a bachelor's degree combined with experience and certification is sufficient for many patient advocacy roles, pursuing a graduate degree can open doors to leadership positions, specialized practice areas, or roles in policy and administration. Relevant master's degrees include Public Health (MPH), Health Administration (MHA), Nursing (MSN), or Social Work (MSW).

These advanced degrees often offer specializations relevant to advocacy, such as health policy, healthcare management, community health education, or gerontology. A graduate degree can provide deeper expertise in system-level issues, research methodologies, and leadership skills.

For those interested in shaping healthcare systems or leading advocacy programs, a graduate education can be a significant asset. It demonstrates a higher level of commitment and expertise in the complex dynamics of healthcare delivery and patient support.

This course provides a high-level view relevant to healthcare administration pathways.

Online and Independent Learning

Essential Topics for Self-Study

For career changers or those supplementing formal education, online learning offers flexible pathways to acquire foundational knowledge. Key areas include medical terminology to understand diagnoses and treatments, and the basics of the healthcare system structure, including different types of providers and facilities.

Understanding healthcare finance is crucial. This includes learning about different insurance models (Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance), billing codes, Explanation of Benefits (EOBs), and the appeals process. Knowledge of relevant healthcare laws, especially HIPAA and patient rights legislation, is also essential.

Developing strong communication and interpersonal skills is vital. Online courses focusing on active listening, conflict resolution, motivational interviewing, and cross-cultural communication can be highly beneficial for effectively interacting with patients, families, and providers.

These online courses cover crucial foundational knowledge for advocates.

Building Practical Skills Online

Beyond theoretical knowledge, effective advocacy requires practical skills. Online platforms increasingly offer courses that incorporate simulations, case studies, and role-playing exercises to help learners practice navigating challenging patient interactions and ethical dilemmas.

Courses focused on communication strategies, negotiation tactics, and conflict resolution can directly translate into improved advocacy skills. Look for courses emphasizing active listening, empathetic communication, and techniques for de-escalating tense situations – skills critical when dealing with stressed patients or navigating disagreements with providers or insurers.

Platforms like OpenCourser aggregate courses from various providers, allowing learners to compare syllabi and find options that include practical application components. Utilizing the "Save to list" feature helps organize potential courses for a personalized learning path.

These courses focus on communication and interaction skills vital for advocacy.

Building Experience and Portfolios

While online courses build knowledge, practical experience is indispensable. Aspiring advocates, especially those changing careers, should seek opportunities to apply their learning. Volunteering at hospitals, patient support groups, or community health clinics can provide invaluable real-world exposure.

Consider offering pro bono (free) advocacy services to friends, family, or community members (while being transparent about your level of experience and limitations). This helps build practical skills in navigating actual healthcare scenarios.

Documenting these experiences is crucial. Maintain records of cases handled (anonymized to protect privacy), challenges overcome, and skills utilized. This forms the basis of a portfolio demonstrating practical competence to potential employers or clients, supplementing formal education and online coursework.

Combining Online Learning with In-Person Opportunities

A hybrid approach often proves most effective. Use online courses for foundational knowledge, specialized topics, and flexible learning. Supplement this with in-person experiences like internships, volunteering, or shadowing experienced advocates.

This combination allows learners to acquire theoretical understanding at their own pace while gaining practical insights, mentorship, and networking opportunities through real-world engagement. Internships, in particular, provide structured exposure to the daily realities of the role within an organizational setting.

Look for local healthcare organizations, non-profits, or advocacy groups that offer volunteer or internship positions. Connecting theoretical learning from online courses with hands-on practice creates a well-rounded foundation for a successful career in patient advocacy.

Career Progression and Advancement

Entry-Level vs. Senior Advocate Roles

Entry-level patient advocacy positions might involve more focused tasks, such as assisting with appointment scheduling, basic insurance inquiries, or providing information within a specific department like patient relations or billing. These roles provide essential experience in navigating healthcare systems and interacting with patients.

As advocates gain experience and expertise (often supplemented by certification), they progress to senior roles. Senior advocates typically handle more complex cases involving intricate medical situations, challenging insurance appeals, ethical dilemmas, or coordinating care across multiple providers and systems. They may also mentor junior staff.

Progression often involves demonstrating strong problem-solving abilities, successful case resolution, deep knowledge of healthcare finance and policy, and excellent communication and negotiation skills. Specialization in areas like oncology, pediatrics, or geriatrics can also lead to advancement.

Transitioning to Policy or Administration

Experienced patient advocates possess unique insights into the systemic barriers and challenges patients face. This ground-level perspective is highly valuable in roles focused on improving the healthcare system itself. Many advocates leverage their experience to transition into health policy or healthcare administration.

In policy roles (often in government agencies, non-profits, or think tanks), advocates contribute to developing legislation, regulations, or organizational policies aimed at improving patient rights, access to care, and healthcare quality. Their practical experience informs evidence-based policy recommendations.

Within healthcare administration, former advocates might move into management positions overseeing patient experience initiatives, quality improvement projects, or advocacy departments within hospitals or health systems. Their focus shifts from individual cases to broader systemic improvements.

Understanding health policy is key for those interested in these transitions.

Entrepreneurial Paths: Private Advocacy

A growing number of experienced patient advocates choose to establish their own private practices. As independent advocates, they contract directly with patients and families, offering personalized navigation and support services on a fee-for-service basis.

This path offers autonomy and the ability to focus deeply on individual client needs outside the constraints of institutional employment. However, it also requires strong business acumen, including marketing, client acquisition, billing, and practice management skills.

Successful private advocates often build reputations within specific niches (e.g., elder care navigation, complex diagnosis support) and develop strong referral networks among physicians, attorneys, and financial planners. It's a challenging but potentially rewarding path for seasoned professionals seeking independence.

This course touches on digital health entrepreneurship, relevant for some private practice models.

Metrics for Evaluating Career Growth

Measuring success and growth in patient advocacy can differ from traditional corporate metrics. While efficiency and case volume might be tracked in some settings, the core value often lies in qualitative outcomes and patient impact.

Key indicators of growth and effectiveness can include positive patient feedback and satisfaction scores, success rates in resolving complex billing or insurance issues, and the ability to navigate increasingly challenging cases. Building a strong reputation and receiving referrals from healthcare professionals or former clients are also important markers.

For those in leadership roles, success might be measured by improvements in system-wide patient experience metrics, successful implementation of patient-centered initiatives, or effective management and development of an advocacy team. Ultimately, growth is often tied to expanding expertise, handling greater complexity, and demonstrably improving patient journeys.

This book offers insights into improving healthcare processes, relevant to demonstrating impact.

Ethical Challenges in Patient Advocacy

Confidentiality in the Digital Age

Maintaining patient confidentiality is a cornerstone of ethical advocacy, made more complex by the prevalence of digital health records (EHRs) and electronic communication. Advocates must be vigilant about protecting patient data, adhering strictly to HIPAA regulations and organizational policies regarding access and sharing of information.

Challenges include ensuring secure communication channels (e.g., encrypted email), understanding who has legitimate access to EHRs, and obtaining proper patient consent before sharing information with family members or other providers. Accidental breaches or misuse of data can have serious legal and ethical consequences.

Advocates must stay informed about best practices for digital privacy and security, using secure platforms and being mindful of the information they document and share electronically. Trust is paramount in the advocate-patient relationship, and safeguarding confidentiality is key to maintaining it.

Managing Conflicts: Patient, Family, and Provider Wishes

Advocates often find themselves navigating disagreements between parties involved in a patient's care. Conflicts can arise between a patient's wishes and their family's preferences, or between the patient/family and the recommendations of the healthcare team.

The advocate's primary allegiance is to the patient (assuming the patient has decision-making capacity). Their role is to ensure the patient's voice is heard and their autonomy respected, facilitating communication to bridge gaps and find common ground where possible. This requires strong mediation and communication skills.

These situations demand careful ethical navigation. Advocates must remain objective, clearly define their role, avoid taking sides inappropriately, and focus on promoting informed decision-making by the patient. Understanding legal frameworks around capacity and surrogate decision-making is also crucial.

These resources delve into ethical considerations and complex conversations.

Advocacy in End-of-Life Decisions

Supporting patients and families during end-of-life care presents unique and profound ethical challenges. Advocates play a crucial role in ensuring patients' wishes regarding treatment preferences, palliative care, and hospice are understood and honored.

This involves facilitating conversations about advance directives (like living wills and healthcare power of attorney), ensuring these documents are legally sound and accessible, and mediating discussions between patients, families, and providers about goals of care when prognosis is poor.

Advocates must provide compassionate support, navigate complex emotions, and ensure decisions align with the patient's stated values and preferences, even when faced with family disagreement or provider uncertainty. Deep empathy, strong communication skills, and knowledge of palliative care principles are essential.

These courses and books touch upon palliative care and end-of-life issues.

Whistleblower Protections and Responsibilities

Occasionally, advocates may encounter situations involving substandard care, safety violations, or unethical practices within a healthcare facility or system. Deciding whether and how to report such issues presents a significant ethical dilemma, balancing patient safety against potential repercussions.

Advocates need to understand internal reporting mechanisms within organizations, as well as external avenues like state licensing boards or patient safety organizations. They must also be aware of whistleblower protection laws, which vary by jurisdiction and circumstance, designed to shield individuals who report misconduct in good faith.

This requires careful judgment, thorough documentation, and an understanding of the potential risks and benefits of reporting. The primary goal is always patient safety and well-being, but advocates must navigate these situations strategically and ethically.

Understanding safety culture and quality improvement is relevant here.

Industry Trends Impacting Patient Advocates

Telehealth Integration Challenges

The rapid expansion of telehealth offers increased access to care but also introduces new challenges for patient advocacy. Advocates must help patients navigate the technology, ensure privacy during virtual visits, and address potential disparities for those lacking digital literacy or reliable internet access.

Advocates may need to assist patients in preparing for virtual appointments, ensuring they can effectively communicate their symptoms and concerns remotely. They also play a role in ensuring telehealth services maintain quality standards and don't inadvertently widen health equity gaps.

Furthermore, coordinating care between virtual and in-person providers adds another layer of complexity that advocates can help manage, ensuring seamless information flow and follow-up across different care modalities.

Value-Based Care Reimbursement Models

The shift from fee-for-service to value-based care models, which reward providers for quality outcomes rather than volume of services, impacts the healthcare landscape. Patient advocates can play a role in this environment by helping patients understand quality metrics and choose high-value providers.

Advocates also help ensure that cost-saving measures within value-based models do not compromise necessary care or patient choice. They can assist patients in navigating bundled payments or accountable care organizations (ACOs), ensuring they receive comprehensive, coordinated care aligned with the model's goals.

Understanding these evolving reimbursement structures allows advocates to better support patients in accessing appropriate, high-quality care within the changing financial realities of healthcare.

Aging Population Demographics

The aging of populations in many countries significantly increases the demand for patient advocacy services. Older adults often face multiple chronic conditions, complex medication regimens, and challenges related to mobility, cognition, and social support, making healthcare navigation particularly difficult.

Advocates specializing in elder care help navigate Medicare/Medicaid, coordinate geriatric care, arrange for home health or long-term care, and protect seniors from potential fraud or neglect. The need for advocates skilled in addressing the unique needs of this demographic is projected to grow substantially.

This demographic shift underscores the importance of the advocacy role in ensuring older adults receive appropriate, person-centered care that respects their autonomy and enhances their quality of life.

These books address health literacy and patient perspectives, crucial for serving diverse populations including the elderly.

AI in Care Coordination Tools

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly being integrated into healthcare, with potential applications in care coordination, data analysis, and even preliminary patient interaction (e.g., chatbots). While AI tools may streamline some administrative tasks or identify potential care gaps, they also raise questions for patient advocates.

Advocates may need to help patients understand how AI is being used in their care and ensure algorithms don't perpetuate biases or overlook individual patient nuances. The human element of empathy, complex problem-solving, and nuanced communication remains critical and is unlikely to be fully replaced by AI.

The future likely involves advocates leveraging AI tools to enhance their efficiency (e.g., managing data, identifying resources) while focusing on the uniquely human aspects of support, communication, and ethical navigation that technology cannot replicate. Staying informed about AI advancements in healthcare will be important for advocates.

Patient Advocate in the Healthcare Career Ladder

Common Previous Roles

Many individuals enter patient advocacy after gaining experience in other healthcare roles. Nursing (Nursing) and Social Work (Social Sciences) are common backgrounds, providing clinical knowledge and experience with patient interaction and resource navigation.

Case management, whether hospital-based or insurer-based, also provides a strong foundation in care coordination and understanding healthcare systems. Professionals from healthcare administration, medical billing, insurance claims processing, or even allied health fields like physical therapy may also transition into advocacy, bringing specific system knowledge.

This prior experience provides context, credibility, and practical skills that are highly transferable to the challenges of patient advocacy. It helps individuals hit the ground running when navigating complex healthcare environments.

These courses relate to common feeder roles like social work and nursing case management.

Lateral Moves to Patient Experience Design

The skills and insights gained as a Patient Advocate are highly relevant to the growing field of Patient Experience (PX). Professionals in PX focus on systematically improving patients' overall journey and interactions with a healthcare organization.

Advocates possess a deep understanding of patient pain points, communication breakdowns, and systemic barriers encountered during care. This makes them well-suited for roles designing and implementing initiatives to enhance patient satisfaction, improve communication workflows, and create more patient-centered environments.

Moving into a PX role often involves a shift from individual case resolution to broader strategy and process improvement, leveraging advocacy experience to inform design decisions that impact many patients.

This course looks at patient journeys, relevant to patient experience design.

Leadership Roles in Advocacy Departments

Within larger healthcare organizations or non-profits, experienced Patient Advocates can advance into leadership positions. This might involve managing a team of advocates, overseeing a patient relations department, or directing an organization's overall advocacy strategy.

Leadership roles require strong management skills, strategic thinking, program development capabilities, and the ability to represent patient interests at higher administrative levels. Leaders are responsible for setting standards, training staff, managing budgets, and demonstrating the value of advocacy services within the organization.

These positions often require significant experience, proven success in complex advocacy cases, and sometimes advanced degrees (like an MHA or MPH) or specialized leadership training.

This course covers leadership principles applicable in healthcare settings.

Cross-Industry Transitions

The skills developed in patient advocacy – communication, problem-solving, negotiation, system navigation, understanding patient needs – are valuable in various sectors beyond direct patient care.

Some advocates transition to roles in the pharmaceutical or medical device industries, often in patient support programs, medical liaison roles, or market access positions where understanding the patient journey is crucial. Others may move into healthcare consulting, advising organizations on patient engagement strategies or regulatory compliance.

Opportunities might also exist in health technology companies developing patient-facing tools, or in insurance companies focusing on member services or complex case management. The ability to understand and navigate the healthcare system from the patient's perspective is a transferable asset.

Frequently Asked Questions (Career Focus)

Can Patient Advocates prescribe medication?

No, Patient Advocates cannot prescribe medication or provide medical treatment. They are not licensed clinical providers like doctors or nurse practitioners. Their role is strictly non-clinical.

Advocates focus on communication, navigation, support, and rights protection. They help patients understand information provided by clinicians, ask relevant questions, and make informed decisions, but they do not offer medical advice or interfere with the clinical judgment of licensed providers.

Maintaining this clear boundary is essential for ethical practice and legal compliance. Advocates empower patients within the healthcare system; they do not replace clinical professionals.

What are typical salary ranges?

Salary ranges for Patient Advocates vary widely based on factors like geographic location, work setting (hospital vs. non-profit vs. private practice), years of experience, level of education, and certification (like BCPA).

Entry-level positions in non-profits or support roles might start lower, while experienced, certified advocates in hospital systems or successful private practices can earn significantly more. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), roles like Health Education Specialists and Community Health Workers (which can encompass some advocacy functions) had median annual wages ranging roughly from $49,000 to $62,000 in May 2023, but specialized or senior advocacy roles could exceed this.

Private practice earnings depend heavily on client volume and fee structures. Thorough research on salary comparison websites for specific locations and employer types is recommended for accurate expectations.

How might AI impact job prospects?

Artificial intelligence is likely to augment rather than replace Patient Advocates. AI tools may automate certain administrative tasks, help analyze large datasets to identify patient needs, or provide initial information via chatbots, potentially freeing up advocates' time.

However, the core aspects of advocacy – empathy, nuanced communication, building trust, navigating complex human emotions, ethical judgment, and creative problem-solving in unique situations – are skills AI currently cannot replicate effectively. The human touch remains central to the role.

Advocates who adapt and learn to leverage AI tools for efficiency may find their roles enhanced. The fundamental need for human guidance and support within a complex, often impersonal healthcare system is expected to persist, ensuring continued demand for skilled advocates.

What are the licensing requirements?

Unlike clinical professions (doctors, nurses), Patient Advocacy generally does not have state-mandated licensing requirements to practice. This means there isn't a government-issued license needed to call oneself a Patient Advocate in most jurisdictions.

However, professional certification, particularly the Board Certified Patient Advocate (BCPA), serves as the industry standard for demonstrating competence and ethical commitment. While not a legal license, employers increasingly prefer or require certification, especially in formal healthcare settings.

It's crucial to distinguish between voluntary professional certification and mandatory state licensure. Always check specific state regulations, as requirements could evolve, but currently, certification is the key credential in the field.

Are Patient Advocates typically unionized?

Unionization among Patient Advocates is less common compared to professions like nursing, particularly in hospital settings where nurses often have strong union representation. However, it's not entirely absent.

If an advocate works within a larger hospital system or organization where other professional groups are unionized, they might fall under an existing bargaining unit, depending on their specific job classification and the union's scope.

In non-profit settings or private practice, unionization is rare. The prevalence depends heavily on the specific employer, region, and the history of labor organization within that workplace.

What are the career longevity considerations?

A career in patient advocacy can be incredibly rewarding but also emotionally demanding. Advocates often deal with patients and families experiencing significant stress, illness, and frustration. Witnessing suffering and navigating bureaucratic obstacles can lead to burnout if not managed carefully.

Successful long-term advocates develop strong coping mechanisms, practice regular self-care, establish clear professional boundaries, and seek peer support or supervision. The ability to manage stress and prevent compassion fatigue is crucial for career longevity.

Despite the challenges, the deep sense of purpose derived from making a tangible difference in people's lives provides strong motivation for many advocates, leading to long and fulfilling careers for those equipped to handle the emotional aspects of the role.

Developing resilience and stress management skills is important for sustainability in this field.

Conclusion

Becoming a Patient Advocate is a path for individuals passionate about empowering others within the complex world of healthcare. It demands a unique mix of empathy, analytical thinking, communication skills, and resilience. While challenges like navigating bureaucracy and managing emotional intensity exist, the opportunity to directly improve patients' experiences and ensure their voices are heard offers profound professional satisfaction. Whether entering through formal education, online learning, or transitioning from another healthcare role, a career in patient advocacy provides a meaningful way to contribute to a more patient-centered healthcare system. For those exploring this rewarding field, resources like the OpenCourser Learner's Guide can offer valuable tips on structuring your educational journey.