Quality Management

Comprehensive Guide to Quality Management

Quality Management is a discipline focused on ensuring that organizations, products, and services consistently meet or exceed customer expectations. It's a multifaceted field that involves establishing a quality policy, planning and assurance, and quality control and improvement. At its core, Quality Management is about creating a culture of excellence where every member of an organization is committed to delivering value. Individuals may find the pursuit of quality engaging due to its direct impact on customer satisfaction and business success. Furthermore, the problem-solving and analytical aspects of improving processes and systems can be intellectually stimulating and professionally rewarding.

For those new to the concept, imagine a restaurant striving to serve the perfect meal every time. Quality Management would involve everything from sourcing the freshest ingredients and training chefs in precise cooking techniques to ensuring the dining environment is pleasant and service is impeccable. It’s about looking at every step of the process to make it the best it can be. The drive to achieve such high standards and the tangible results of these efforts are often what draw people to this field.

Introduction to Quality Management

This section delves into the fundamental concepts of Quality Management, tracing its historical development and outlining its core tenets. We will explore the contributions of key figures who shaped the field and examine globally recognized standards that guide quality practices today. Understanding these foundational elements is crucial for anyone looking to implement or improve quality initiatives within an organization, regardless of the industry.

Defining Quality Management and Its Historical Roots

Quality Management, at its essence, is a systematic approach to ensuring that all activities within an organization are designed, implemented, and controlled to meet and exceed customer expectations and achieve organizational objectives. It encompasses a wide range of processes and methodologies aimed at consistently delivering high-quality products and services. The concept isn't new; its roots can be traced back to medieval Europe, where craftsmen's guilds established strict standards for product quality.

The Industrial Revolution brought about significant changes, with a shift towards factory systems and an emphasis on inspection to identify and remove defective goods. Early 20th-century thinkers like Frederick Winslow Taylor began to systematically study manufacturing efficiency. A pivotal moment arrived in the 1920s with Walter Shewhart's introduction of statistical sampling techniques and statistical process control, laying the groundwork for modern quality control. This marked a significant evolution from mere inspection to a more proactive approach focused on controlling processes to prevent defects.

The post-World War II era saw a quality revolution, particularly in Japan, which, with the guidance of figures like W. Edwards Deming and Joseph M. Juran, transformed its reputation for shoddy exports into one of global leadership in manufacturing quality. This period saw the development and refinement of many quality management philosophies and tools that are still in use today. By the 1970s, Japanese companies were outcompeting U.S. manufacturers in key sectors, prompting Western businesses to adopt and adapt these quality principles.

Core Principles: Customer Focus and Continuous Improvement

Two of the most fundamental principles underpinning modern Quality Management are customer focus and continuous improvement. Customer focus dictates that the quality of a product or service is ultimately determined by the customer. Organizations must therefore deeply understand their customers' needs and expectations and design their products, services, and processes accordingly. This involves actively seeking customer feedback and using it to drive improvements.

Continuous improvement, often referred to by the Japanese term "Kaizen," is the ongoing effort to enhance processes, products, and services. This principle recognizes that quality is not a static goal but a dynamic journey. It involves all employees in an organization in the pursuit of incremental improvements over time. This relentless pursuit of betterment helps organizations adapt to changing customer needs, improve efficiency, reduce waste, and maintain a competitive edge. Many quality management frameworks, such as Total Quality Management (TQM) and ISO 9001, have these principles at their core.

These principles are interconnected. A strong customer focus provides the direction for continuous improvement efforts, ensuring that improvements are aligned with what customers value. Conversely, a commitment to continuous improvement enables an organization to better meet and exceed customer expectations over time. For example, an organization might gather customer feedback (customer focus) indicating that delivery times are too long. This would then trigger a continuous improvement project to analyze and streamline the delivery process.

Key Contributors: Deming, Juran, and Ishikawa

Several influential thinkers have shaped the field of Quality Management. W. Edwards Deming, an American statistician, is often hailed as a father of modern quality control. He emphasized the importance of management's role in quality, advocating for a systematic approach to problem-solving and continuous improvement, famously encapsulated in his Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle. Deming's 14 Points for Management provided a roadmap for organizations seeking to transform their quality practices. His work was pivotal in Japan's post-war economic miracle.

Joseph M. Juran, another key figure who consulted extensively in Japan, viewed quality as "fitness for use." He stressed the importance of quality planning, quality control, and quality improvement, a concept known as the Juran Trilogy. Juran also highlighted the Pareto principle (the 80/20 rule) in quality, suggesting that a small number of causes often account for the majority of problems. He believed quality should be managed as a core business function, with strong leadership commitment.

Kaoru Ishikawa, a Japanese organizational theorist, made significant contributions, including the popularization of quality circles and the development of the Ishikawa diagram (also known as the fishbone or cause-and-effect diagram). The fishbone diagram is a visual tool used to identify potential causes of a problem, helping teams to brainstorm and analyze issues systematically. Ishikawa emphasized that quality improvement should be a company-wide effort involving all employees.

These courses can help build a foundation in the core concepts championed by these pioneers.

Global Standards: Understanding ISO 9001

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) develops and publishes international standards, and ISO 9001 is the world's most recognized standard for Quality Management Systems (QMS). It provides a framework and a set of principles that organizations can use to ensure they consistently meet customer and regulatory requirements, and to enhance customer satisfaction. First published in 1987, ISO 9001 has undergone several revisions, with the latest version being ISO 9001:2015.

ISO 9001 is based on several quality management principles, including a strong customer focus, the involvement of top management, a process approach, and continual improvement. It is designed to be applicable to any organization, regardless of its size, type, or the products and services it provides. Achieving ISO 9001 certification, while not mandatory in all industries, can enhance an organization's credibility, improve customer satisfaction, increase operational efficiency, and open up new market opportunities. The standard requires organizations to document their QMS, implement its processes, and continually monitor and improve its effectiveness.

The 2015 revision of ISO 9001 introduced some significant changes, including a greater emphasis on risk-based thinking, a new high-level structure (Annex SL) to make it easier to integrate with other management system standards, increased leadership requirements, and a focus on achieving intended results. More recent amendments in 2024 also require organizations to consider the effects of climate change on their QMS. As of 2025, further revisions are anticipated to address the evolving business environment, including aspects like resilience, supply chain management, and sustainability.

For those looking to understand and implement this global standard, the following courses offer valuable insights.

These books provide in-depth knowledge about ISO 9000 standards.

Quality Management Frameworks

Various frameworks provide structured approaches to implementing Quality Management. These frameworks offer principles, methodologies, and tools that organizations can adapt to their specific needs and contexts. This section will explore some of the most prominent frameworks, including Total Quality Management (TQM), Six Sigma, Lean manufacturing, and the Balanced Scorecard, comparing their core ideas and how they contribute to achieving operational excellence.

Total Quality Management (TQM) Principles

Total Quality Management (TQM) is a management philosophy that emphasizes the continuous pursuit of quality in all aspects of an organization's operations, with the ultimate goal of customer satisfaction. It emerged as a significant approach, particularly in the U.S., in response to Japan's manufacturing successes. TQM requires the involvement of all employees, from top leadership to frontline staff, in improving processes, products, and services.

While there isn't a single, universally agreed-upon definition, TQM is generally characterized by a set of core principles. These typically include: a strong customer focus, total employee involvement and empowerment, a process-centered approach, integrated systems, a strategic and systematic approach, continual improvement, fact-based decision-making, and effective communication. Some models also highlight foundational elements like ethics, integrity, and trust as crucial for TQM success.

The "total" in TQM signifies that quality is not just the responsibility of a dedicated quality department but is ingrained in the culture and practices of the entire organization. "Management" implies a focused and systematic effort, driven by leadership, to actively manage and improve quality. TQM aims to prevent defects and errors from occurring in the first place, rather than just detecting and correcting them after the fact.

This book offers a comprehensive introduction to TQM.

Six Sigma Methodologies (DMAIC, DMADV)

Six Sigma is a data-driven quality improvement methodology focused on minimizing defects and variability in processes. Developed by Motorola in the 1980s, it aims to achieve a quality level of no more than 3.4 defects per million opportunities. Six Sigma uses a structured approach and a set of statistical tools to identify and eliminate the root causes of errors. Two primary methodologies are employed within the Six Sigma framework: DMAIC and DMADV.

DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) is used for improving existing processes.

- Define: Clearly define the problem, project goals, and customer (internal and external) requirements.

- Measure: Measure the current process performance and collect relevant data.

- Analyze: Analyze the data to identify root causes of defects and opportunities for improvement.

- Improve: Develop and implement solutions to address the root causes and improve the process.

- Control: Implement controls to sustain the improvements and monitor future process performance.

DMADV (Define, Measure, Analyze, Design, Verify) is used for designing new processes or products, or for redesigning existing ones when incremental improvement is not sufficient.

- Define: Define project goals based on customer demands and enterprise strategy.

- Measure: Measure and identify CTQs (Critical to Quality characteristics), product capabilities, production process capability, and risks.

- Analyze: Analyze to develop and design alternatives, create high-level design and evaluate design capability to select the best design.

- Design: Design details, optimize the design, and plan for design verification. This phase may require simulations.

- Verify: Verify the design, set up pilot runs, implement the production process and hand it over to the process owner(s).

Professionals can become certified in Six Sigma at various levels (e.g., Yellow Belt, Green Belt, Black Belt), indicating their proficiency in applying its methodologies and tools.

These courses provide an introduction to Six Sigma principles and belt certifications.

This book is a well-regarded resource for understanding Six Sigma.

You may also wish to explore this related topic.

Lean Manufacturing Integration

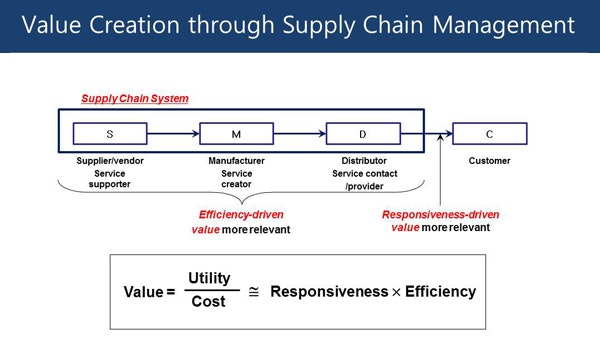

Lean manufacturing, often simply called "Lean," is a production philosophy focused on maximizing customer value while minimizing waste. Originating from the Toyota Production System, Lean identifies seven primary types of waste (often remembered by the acronym TIM WOODS: Transportation, Inventory, Motion, Waiting, Overproduction, Over-processing, Defects). Some modern interpretations add an eighth waste: Non-Utilized Talent. The core idea is to create more value for customers with fewer resources.

Lean principles are highly complementary to Quality Management. By focusing on waste reduction, Lean inherently improves quality by eliminating opportunities for errors and inefficiencies. For instance, reducing excess inventory can expose production problems that were previously hidden. Simplifying processes (reducing motion and over-processing) can lead to fewer mistakes and more consistent output. The emphasis on "flow" and "pull" systems in Lean also contributes to better quality by ensuring that work is done only when needed and in the right sequence.

Many organizations integrate Lean principles with other quality frameworks like Six Sigma, leading to methodologies such as "Lean Six Sigma." This combination leverages Lean's focus on speed and waste reduction with Six Sigma's emphasis on defect reduction and process control. The integration allows organizations to tackle a broader range of improvement opportunities, leading to more significant and sustainable results in both efficiency and quality. The goal is to create processes that are not only high quality but also fast, efficient, and responsive to customer needs.

Consider these courses to learn more about Lean principles and their application.

Explore this topic for a broader understanding of Lean concepts.

Balanced Scorecard Approach

The Balanced Scorecard (BSC) is a strategic planning and management system used to align business activities to the vision and strategy of the organization, improve internal and external communications, and monitor organization performance against strategic goals. Developed by Drs. Robert Kaplan and David Norton, the BSC suggests that we view the organization from four perspectives to develop metrics, collect data, and analyze it relative to these perspectives:

- The Learning and Growth Perspective: This perspective focuses on the intangible assets of an organization, primarily its people, culture, and infrastructure. It addresses questions like: "To achieve our vision, how will we sustain our ability to change and improve?" Key areas include employee skills, information systems, and organizational alignment.

- The Business Process Perspective: This perspective looks at internal operational processes. It asks: "To satisfy our shareholders and customers, what business processes must we excel at?" It focuses on efficiency, quality, and innovation in processes like operations management, customer management, and innovation.

- The Customer Perspective: This perspective considers the organization's performance from the customer's point of view. The central question is: "To achieve our vision, how should we appear to our customers?" Metrics here often relate to customer satisfaction, market share, customer retention, and brand perception.

- The Financial Perspective: This perspective assesses the organization's financial performance and strategic use of financial resources. It addresses the question: "To succeed financially, how should we appear to our shareholders?" Typical metrics include profitability, revenue growth, and return on investment.

While not exclusively a quality management framework, the Balanced Scorecard integrates quality as a key component within its various perspectives, particularly the Customer and Business Process perspectives. By measuring and managing performance across these balanced areas, organizations can ensure that their quality initiatives are aligned with overall strategic objectives and contribute to long-term success. It helps to translate an organization's mission and strategy into a comprehensive set of performance measures that provides the framework for a strategic measurement and management system.

The BSC encourages a more holistic view of organizational performance beyond traditional financial metrics, ensuring that critical non-financial aspects, including quality, are actively managed and improved.

Quality Control Techniques

Quality Control (QC) is a critical component of Quality Management, focusing on the operational techniques and activities used to fulfill requirements for quality. It involves monitoring specific project results to determine if they comply with relevant quality standards and identifying ways to eliminate causes of unsatisfactory performance. This section will detail several widely used QC techniques that empower organizations to maintain and enhance the quality of their products and services through data-driven decision-making.

Statistical Process Control (SPC) Charts

Statistical Process Control (SPC) is a method of quality control which employs statistical methods to monitor and control a process. A key tool in SPC is the control chart, first developed by Walter Shewhart in the 1920s. Control charts are graphs used to study how a process changes over time. Data are plotted in time order. A control chart always has a central line for the average, an upper line for the upper control limit, and a lower line for the lower control limit.

These lines are determined from historical data. By comparing current data to these lines, one can draw conclusions about whether the process variation is consistent (in control) or is unpredictable (out of control, affected by special causes of variation). Control charts help distinguish between common cause variation (inherent in the process) and special cause variation (due to assignable causes). When a process is in control, it is stable and predictable. If special causes are present, the process is unstable, and corrective action is needed to identify and eliminate these causes.

There are various types of control charts designed for different types of data (e.g., X-bar and R charts for variable data, p-charts and c-charts for attribute data). The effective use of SPC charts allows organizations to monitor process stability, identify areas for improvement, reduce variability, and ultimately enhance product or service quality. They are fundamental tools for data-driven decision-making in manufacturing and service industries alike.

This book provides a detailed understanding of statistical quality control.

You might find this topic relevant if you wish to delve deeper into statistical methods.

Root Cause Analysis (Fishbone Diagrams)

Root Cause Analysis (RCA) is a systematic problem-solving method aimed at identifying the fundamental causes of problems or incidents. Instead of merely addressing the symptoms, RCA seeks to find the underlying issues that, if corrected, would prevent recurrence. One popular and effective tool used in RCA is the Fishbone Diagram, also known as the Ishikawa Diagram or Cause-and-Effect Diagram.

Developed by Kaoru Ishikawa, the Fishbone Diagram visually organizes potential causes of a specific problem (the "effect"). The problem statement forms the "head" of the fish, and a central "spine" extends from it. Major categories of causes branch off from the spine like fishbones. Common categories, particularly in manufacturing, include the "6 Ms": Manpower (People), Methods, Machines, Materials, Measurements, and Mother Nature (Environment). Service industries might use categories like the "4 Ss" (Surroundings, Suppliers, Systems, Skills) or "5 Ps" (People, Provisions, Procedures, Place, Patrons).

Teams brainstorm potential causes within each category, often asking "Why?" multiple times (a technique sometimes called the "5 Whys") to drill down to deeper, more fundamental causes. These are then added as smaller "bones" branching off the main category bones. The Fishbone Diagram facilitates a structured brainstorming session, encourages team participation, and helps ensure a comprehensive exploration of potential causes before focusing on solutions.

This course offers practical skills in using quality tools, including those for root cause analysis.

Failure Mode Effects Analysis (FMEA)

Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) is a systematic, proactive method for evaluating a process to identify where and how it might fail and to assess the relative impact of different failures. The goal of FMEA is to identify, prioritize, and limit or eliminate potential failures before they occur. It is a tool used to prevent problems rather than react to them after they happen.

The FMEA process typically involves a cross-functional team that identifies potential failure modes (ways in which a product or process can fail to meet requirements), the potential effects of each failure mode (the consequences for the customer or downstream processes), and the potential causes of each failure mode. For each failure mode, the team assigns severity, occurrence, and detection ratings.

- Severity (S): How serious is the effect if the failure occurs?

- Occurrence (O): How likely is the failure to occur?

- Detection (D): How easily can the failure be detected before it reaches the customer?

These ratings are then multiplied to calculate a Risk Priority Number (RPN = S x O x D). Failure modes with higher RPNs are typically prioritized for corrective action. The team then develops and implements action plans to reduce the risk associated with high-priority failure modes, often by reducing the likelihood of occurrence or improving detection methods. FMEA is a living document and should be reviewed and updated as designs or processes change.

You may wish to explore this topic for more on risk assessment.

Acceptance Sampling Methods

Acceptance sampling is a statistical quality control technique used to determine whether to accept or reject a batch of products based on the inspection of a random sample. Instead of inspecting 100% of the items, which can be costly and time-consuming (and sometimes destructive), a smaller sample is selected and inspected. The results from the sample are then used to make an inference about the quality of the entire lot.

Acceptance sampling plans specify the sample size (n) to be inspected and the acceptance number (c), which is the maximum number of defective items allowed in the sample for the lot to be accepted. If the number of defectives found in the sample is less than or equal to the acceptance number, the lot is accepted. If it exceeds the acceptance number, the lot is rejected (which might mean 100% inspection, rework, or return to the supplier).

There are different types of acceptance sampling plans, including single sampling plans, double sampling plans, and multiple sampling plans. The choice of plan depends on factors such as the cost of inspection, the cost of passing defective items, and the desired level of quality assurance. While acceptance sampling can be a cost-effective way to assess lot quality, it does involve risks: the risk of rejecting a good-quality lot (producer's risk or Type I error) and the risk of accepting a poor-quality lot (consumer's risk or Type II error). These risks are inherent in any sampling procedure and must be considered when designing a sampling plan.

This book provides a comprehensive overview of various quality tools, including sampling methods.

Quality Assurance Systems

Quality Assurance (QA) focuses on providing confidence that quality requirements will be fulfilled. It is a proactive process that aims to prevent defects by focusing on the processes used to make products or deliver services. This section will explore the key components of a robust Quality Assurance system, including the importance of documentation, the role of internal audits, mechanisms for corrective and preventive actions, and the processes involved in obtaining certifications.

Documentation Requirements

Comprehensive and well-organized documentation is a cornerstone of any effective Quality Assurance system. Documentation serves multiple critical purposes: it defines the quality standards and procedures, ensures consistency in operations, provides a basis for training, facilitates audits, and demonstrates compliance with regulatory and customer requirements. Without clear documentation, processes can become inconsistent, leading to variations in quality and potential non-conformances.

Key types of documentation in a QMS typically include a quality manual, which provides an overview of the QMS and its alignment with applicable standards (like ISO 9001). Procedures describe how specific activities are to be performed. Work instructions provide detailed step-by-step guidance for carrying out tasks. Records provide evidence of activities performed and results achieved (e.g., inspection reports, audit findings, training records). Forms are used to collect and record data in a standardized manner.

Effective documentation should be clear, concise, accurate, and readily accessible to those who need it. It should also be controlled, meaning there are processes in place for creating, reviewing, approving, distributing, revising, and archiving documents. Good documentation practices ensure that everyone in the organization understands their roles and responsibilities regarding quality and has the information they need to perform their work correctly and consistently.

Internal Audit Processes

Internal audits are a vital component of a Quality Assurance system, providing a systematic and independent examination to determine whether quality activities and related results comply with planned arrangements and whether these arrangements are implemented effectively and are suitable to achieve objectives. Internal audits are conducted by an organization's own personnel (or by external parties on its behalf) and serve as a management tool for verifying and improving the effectiveness of the QMS.

The internal audit process typically involves several stages: planning the audit (defining scope, objectives, and criteria), preparing for the audit (reviewing relevant documentation, developing checklists), conducting the audit (gathering evidence through interviews, observation, and document review), reporting the audit findings (documenting conformances and non-conformances), and following up on corrective actions. The findings from internal audits provide valuable feedback to management on the performance of the QMS and highlight areas where improvements are needed.

Internal audits should be conducted by personnel who are independent of the area being audited to ensure objectivity. Auditors should be trained in auditing techniques and have a good understanding of the QMS and applicable standards. Regularly scheduled internal audits help ensure ongoing compliance, identify opportunities for improvement, and prepare the organization for external certification audits.

This course is designed for those interested in becoming QMS auditors.

Corrective and Preventive Actions (CAPA)

Corrective and Preventive Actions (CAPA) are essential processes within a Quality Assurance system for addressing and eliminating the causes of existing non-conformities (corrective action) and potential non-conformities (preventive action). The goal of CAPA is to prevent the recurrence or occurrence of problems, thereby continuously improving the QMS and the quality of products and services.

Corrective Action is taken to eliminate the causes of a detected non-conformity or other undesirable situation. The process typically involves:

- Identifying the non-conformity (e.g., through customer complaints, internal audits, process monitoring).

- Investigating the root cause of the non-conformity.

- Developing and implementing actions to eliminate the root cause.

- Verifying the effectiveness of the corrective actions to ensure the problem does not recur.

Preventive Action is taken to eliminate the causes of a potential non-conformity or other undesirable potential situation. This proactive process involves:

- Identifying potential problems or risks (e.g., through FMEA, trend analysis, employee suggestions).

- Analyzing the potential causes of these problems.

- Developing and implementing actions to prevent their occurrence.

- Reviewing the effectiveness of the preventive actions.

A robust CAPA system ensures that problems are not just fixed superficially but are thoroughly investigated to address their underlying causes. It is a critical driver of continuous improvement within a QMS.

Certification Processes

Obtaining certification for a Quality Management System, such as ISO 9001 certification, is a formal process by which an accredited third-party certification body assesses an organization's QMS against the requirements of a specific standard. Certification provides independent verification that the organization has implemented an effective QMS and is committed to quality.

The certification process typically involves several key steps. First, the organization must develop and implement its QMS in accordance with the chosen standard. This includes documenting its processes, training employees, and conducting internal audits and management reviews. Once the QMS is established and has been operational for a period, the organization selects an accredited certification body. The certification body then conducts an audit, often in two stages: a Stage 1 audit (documentation review and readiness assessment) and a Stage 2 audit (on-site assessment of QMS implementation and effectiveness).

If the audit is successful and the organization is found to be in conformance with the standard, the certification body issues a certificate. This certification is typically valid for a set period (e.g., three years for ISO 9001), during which the certification body will conduct periodic surveillance audits to ensure ongoing compliance. At the end of the certification cycle, a recertification audit is required to renew the certificate. Achieving and maintaining certification requires a sustained commitment to the QMS and continuous improvement.

This book can be a useful resource for understanding certification systems.

Career Pathways in Quality Management

A career in Quality Management offers diverse opportunities across various industries, from manufacturing and healthcare to software development and service sectors. Professionals in this field play a crucial role in ensuring that products, services, and processes meet established standards and customer expectations. This section outlines typical career trajectories, from entry-level positions to executive roles, and discusses the importance of certifications in advancing one's career in Quality Management.

For those considering a pivot into this field, or for recent graduates, it's encouraging to know that the skills developed in Quality Management – such as analytical thinking, problem-solving, attention to detail, and communication – are highly transferable and valued. The path may require dedication and continuous learning, but the impact you can make on an organization's success and customer satisfaction can be deeply rewarding. While the journey might present challenges, remember that every expert was once a beginner. Setting realistic expectations and celebrating milestones along the way will be key to a fulfilling career.

Entry-Level Roles (e.g., Quality Technician, Inspector)

Entry-level positions in Quality Management often serve as the gateway to the field, providing foundational experience in quality principles and practices. Roles like Quality Technician or Quality Inspector are common starting points. These professionals are typically responsible for hands-on tasks related to monitoring and verifying quality.

Quality Technicians often work closely with Quality Engineers and Managers. Their duties may include performing inspections of raw materials, in-process components, and finished products using various measurement tools and techniques. They might also be involved in calibrating inspection equipment, collecting and analyzing quality data, assisting with root cause analysis of defects, and maintaining quality documentation. Strong attention to detail, an understanding of basic quality tools, and good record-keeping skills are essential.

Quality Inspectors primarily focus on examining products and materials for defects or deviations from specifications. They follow established inspection procedures, use measuring instruments, and record their findings. Inspectors play a crucial role in preventing defective products from reaching customers. These entry-level roles provide invaluable experience in understanding manufacturing processes, quality standards, and the practical application of quality control techniques. They form the bedrock upon which a successful career in quality can be built.

You may wish to explore these careers if you're interested in entry-level quality roles.

This handbook is a valuable resource for aspiring quality inspectors.

Mid-Career Positions (e.g., Quality Engineer, Quality Manager)

As professionals gain experience and expertise, they can advance to mid-career roles such as Quality Engineer or Quality Manager. These positions involve more responsibility, strategic thinking, and leadership. Quality Engineers are typically involved in designing, implementing, and improving quality systems and processes. They may develop quality plans, conduct FMEAs, analyze quality data to identify trends and areas for improvement, lead problem-solving teams, and work with suppliers to ensure the quality of incoming materials. A strong understanding of statistical methods, quality improvement methodologies (like Six Sigma or Lean), and relevant industry standards is often required.

Quality Managers oversee the overall quality management system of an organization or a specific department. Their responsibilities often include developing and implementing quality policies and procedures, ensuring compliance with standards and regulations, managing the internal audit program, overseeing the CAPA system, liaising with customers and regulatory bodies on quality matters, and leading and mentoring quality staff. Quality Managers need strong leadership, communication, and project management skills, in addition to a comprehensive understanding of quality principles and practices. They play a pivotal role in fostering a culture of quality within the organization.

These roles offer the opportunity to make a significant impact on an organization's performance and customer satisfaction. The average salary for a Quality Manager in the US can be around $76k, according to PayScale, though this can vary based on experience, location, and industry. The University of Minnesota Online indicates salary ranges for Quality Assurance Managers between $55,000-$80,000.

These careers represent typical mid-level paths in Quality Management.

This course can help prepare individuals for management roles in quality.

Executive Roles (e.g., Director of Quality, VP of Quality)

At the executive level, Quality Management professionals can ascend to roles such as Director of Quality or Vice President (VP) of Quality. These senior leadership positions involve setting the strategic direction for quality within the organization and ensuring that the QMS supports overall business objectives. Executives in these roles are responsible for championing a culture of quality throughout the entire company, from the top down.

Directors and VPs of Quality typically have extensive experience and a deep understanding of quality management principles, frameworks, and industry best practices. Their responsibilities often include developing and deploying the corporate quality strategy, establishing quality goals and metrics that align with business goals, overseeing quality assurance and quality control functions across multiple sites or business units, managing relationships with key stakeholders (including regulatory agencies and major customers) on quality-related matters, and driving enterprise-wide continuous improvement initiatives. They are also instrumental in ensuring that the organization adapts to evolving quality standards and customer expectations.

These executive roles require exceptional leadership, strategic thinking, communication, and influencing skills. They must be able to inspire and motivate teams, manage significant budgets, and make high-stakes decisions that impact the organization's reputation and bottom line. A strong business acumen, coupled with technical expertise in quality, is essential for success at this level.

Certifications (ASQ, CQE, etc.)

Professional certifications play a significant role in the Quality Management field, validating an individual's knowledge, skills, and experience. Organizations like the American Society for Quality (ASQ) offer a wide range of globally recognized certifications. These credentials can enhance career prospects, demonstrate commitment to the profession, and often lead to higher earning potential.

Some well-known ASQ certifications include:

- Certified Quality Engineer (CQE): For professionals who understand the principles of product and service quality evaluation and control.

- Certified Quality Auditor (CQA): For professionals who understand the standards and principles of auditing and the auditing techniques of examining, questioning, evaluating, and reporting to determine a quality system's adequacy and deficiencies.

- Certified Manager of Quality/Organizational Excellence (CMQ/OE): For professionals who lead and champion process-improvement initiatives—everywhere from small businesses to multinational corporations—that can have regional or global focus in a variety of service and industrial settings.

- Certified Six Sigma Black Belt (CSSBB): For professionals who can explain Six Sigma philosophies and principles, including supporting systems and tools. A Black Belt should demonstrate team leadership, understand team dynamics, and assign team member roles and responsibilities.

- Certified Quality Inspector (CQI): For quality professionals who, in support of and under the direction of quality engineers, supervisors, or technicians, can use the proven techniques included in the body of knowledge.

Many other organizations and industry-specific bodies also offer relevant certifications. Preparing for and obtaining these certifications often requires dedicated study and practical experience. Online courses and resources can be valuable aids in this preparation process. While a degree provides foundational knowledge, certifications often focus on the practical application of specific quality tools and methodologies, making certified individuals highly sought after by employers.

Consider these courses if you are interested in pursuing certifications.

You may also find this career path interesting if you are focused on auditing.

Educational Requirements

Embarking on a career in Quality Management typically involves a combination of formal education, specialized training, and practical experience. While specific requirements can vary by industry and role, a solid educational foundation is generally expected. This section outlines the common academic pathways, including relevant bachelor's and master's degrees, and highlights the role of professional development courses and certification preparation resources in building the necessary competencies for a successful career in this field.

Relevant Bachelor's Degrees (e.g., Industrial Engineering, Business Administration)

A bachelor's degree is often the minimum educational requirement for many entry-level and mid-management positions in Quality Management. Several fields of study can provide a strong foundation. A Bachelor of Science in Industrial Engineering is highly relevant, as it focuses on designing and improving systems and processes, which is central to quality. Curricula often include courses in statistics, operations research, production planning, and quality control.

A bachelor's degree in Business Administration or Management can also be a suitable pathway, particularly if it includes a concentration or coursework in operations management, supply chain management, or quality management. These programs provide a broader understanding of business functions, which is valuable for Quality Managers who need to align quality initiatives with overall business strategy. Some universities offer specialized Bachelor's degrees in Quality Management or Manufacturing Management with a quality focus. These programs provide in-depth knowledge of quality principles, tools, and systems. Other relevant undergraduate degrees might include fields like general engineering, statistics, or even specific scientific disciplines depending on the industry (e.g., chemistry or biology for pharmaceutical quality).

Regardless of the specific major, coursework in statistics, data analysis, problem-solving, and communication will be highly beneficial. Many online programs are also available, offering flexibility for working professionals or those seeking to transition into the field. OpenCourser provides a platform to explore various business and engineering degrees and courses that can lead to a career in Quality Management.

Specialized Master's Programs

For those seeking advanced knowledge and leadership roles in Quality Management, pursuing a specialized master's degree can be a valuable investment. Master's programs often delve deeper into advanced quality methodologies, strategic quality planning, organizational leadership, and research in quality. Common degrees include a Master of Science (MS) in Quality Management, Industrial Engineering (with a quality specialization), Operations Management, or an MBA with a concentration in Quality Management or Operations.

These graduate programs typically equip students with advanced analytical skills, a strategic perspective on quality, and the ability to lead complex quality improvement initiatives. Coursework might cover topics such as advanced statistical process control, design of experiments, reliability engineering, Lean Six Sigma Black Belt methodologies, supply chain quality management, and quality leadership. Many programs also involve a capstone project or thesis, allowing students to apply their learning to real-world quality challenges.

A master's degree can open doors to higher-level management and consulting positions and may be preferred or required for certain specialized roles or industries. It can also provide a pathway for individuals with undergraduate degrees in other fields to transition into Quality Management. As with bachelor's programs, many universities offer flexible online master's options.

Professional Development Courses

Continuous learning is crucial in the ever-evolving field of Quality Management. Professional development courses offer a flexible and targeted way for individuals to acquire new skills, stay updated on the latest trends and standards, and enhance their existing knowledge. These courses can range from short online modules focusing on specific tools or techniques to more comprehensive programs leading to certificates.

Online learning platforms like OpenCourser are invaluable resources for finding relevant professional development courses. Learners can find courses on topics such as ISO 9001 implementation, specific quality control techniques (like SPC or FMEA), Lean principles, Six Sigma methodologies at various belt levels, auditing skills, and risk management. These courses are suitable for individuals at all career stages, from those new to the field seeking foundational knowledge to experienced professionals looking to specialize or refresh their skills.

Many online courses offer certificates upon completion, which can be a valuable addition to a resume. They allow learners to study at their own pace and often provide practical, job-relevant skills that can be immediately applied in the workplace. Furthermore, professional development courses can help individuals prepare for formal certification exams offered by organizations like ASQ.

The following are some introductory courses that can serve as excellent starting points for professional development in quality management.

Certification Preparation Resources

As discussed earlier, professional certifications (like ASQ's CQE, CQA, CMQ/OE) are highly valued in the Quality Management field. Preparing for these rigorous exams requires dedicated effort and access to quality study materials. Numerous resources are available to help candidates prepare effectively, including online courses specifically designed for certification preparation.

These preparation courses often cover the specific Body of Knowledge (BoK) for each certification, providing in-depth explanations of concepts, practice questions, and simulated exams. They can help candidates identify their strengths and weaknesses, focus their study efforts, and become familiar with the exam format. Beyond dedicated prep courses, textbooks, study guides, and practice exam software are also common resources.

Many online platforms offer courses that align with the content of various quality certifications. For instance, courses on Six Sigma can help prepare for Green Belt or Black Belt certifications, while courses on ISO 9001 auditing can be beneficial for aspiring Certified Quality Auditors. OpenCourser's extensive catalog can help individuals find courses that match their certification goals. Additionally, joining study groups, participating in online forums, and seeking mentorship from certified professionals can also enhance preparation efforts.

These courses are specifically geared towards those preparing for quality management certifications or seeking to master key quality standards.

Technological Impact on Quality Management

Technology is rapidly transforming the landscape of Quality Management. From automated inspection systems to advanced data analytics, technological innovations are providing new tools and capabilities to enhance quality processes, improve efficiency, and enable more proactive quality control. This section will explore some of the key technological advancements impacting the field, including automation, Big Data, Artificial Intelligence (AI), and Blockchain.

Automated Quality Control Systems

Automation is playing an increasingly significant role in Quality Control. Automated Quality Control (AQC) systems utilize technology to perform inspections, measurements, and tests with minimal human intervention. This can range from simple sensor-based checks on a production line to sophisticated machine vision systems capable of detecting minute defects at high speeds.

The benefits of AQC are numerous. Automation can significantly increase the speed and efficiency of inspection processes, allowing for 100% inspection where manual methods might only permit sampling. It can also improve the accuracy and consistency of measurements, reducing human error and subjectivity. Automated systems can operate continuously, 24/7, without fatigue, leading to greater throughput and productivity. Furthermore, AQC systems can automatically collect and record quality data, providing a rich dataset for analysis and process improvement.

Examples of AQC include coordinate measuring machines (CMMs) for precise dimensional inspection, automated optical inspection (AOI) systems in electronics manufacturing, and robotic systems equipped with sensors for various quality checks. As automation technologies become more advanced and cost-effective, their adoption in quality control is expected to continue growing across diverse industries.

Big Data Analytics Applications

The proliferation of sensors, interconnected devices (IoT), and digital systems has led to an explosion in the volume, velocity, and variety of data available to organizations – commonly referred to as Big Data. In Quality Management, Big Data analytics offers powerful capabilities to extract meaningful insights from these vast datasets, enabling more informed decision-making and proactive quality improvements.

By analyzing large volumes of historical and real-time data from various sources (e.g., production processes, supplier performance, customer feedback, field failures), organizations can identify patterns, trends, and correlations that might not be apparent with traditional analytical methods. This can help in predicting potential quality issues before they occur, identifying the root causes of defects more accurately, optimizing process parameters for better quality outcomes, and understanding customer preferences and pain points in greater detail.

For example, manufacturers can use Big Data analytics to monitor equipment health and predict maintenance needs, thereby preventing breakdowns that could lead to quality problems. Retailers can analyze customer purchase patterns and social media sentiment to identify emerging quality concerns. The ability to harness Big Data effectively is becoming a key competitive differentiator in achieving superior quality performance.

This course provides insights into how data analytics can be applied in a quality context.

AI in Predictive Quality Analysis

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are taking quality analysis to the next level by enabling predictive quality capabilities. AI algorithms can learn from historical quality data to identify complex patterns and build predictive models that forecast the likelihood of future quality events, such as defects, failures, or non-conformances.

Predictive quality analysis allows organizations to move from a reactive or even proactive stance to a truly predictive one. Instead of waiting for a problem to occur or trying to prevent known failure modes, AI can identify leading indicators of potential issues that may not yet be apparent to human operators or traditional statistical methods. This allows for early intervention to prevent problems from materializing, thereby reducing scrap, rework, warranty costs, and customer dissatisfaction.

Applications of AI in predictive quality include using machine learning to analyze sensor data from manufacturing equipment to predict when a component is likely to fail, using natural language processing (NLP) to analyze customer feedback and service reports to identify emerging product issues, and using computer vision powered by AI to detect subtle defects in images or videos with greater accuracy than human inspectors. As AI technology matures, its role in transforming quality management practices will only continue to expand.

Blockchain for Supply Chain Traceability

Blockchain technology, originally known for its application in cryptocurrencies, is finding new uses in enhancing supply chain traceability and quality assurance. A blockchain is a distributed, immutable ledger that can securely record transactions and track assets. In the context of supply chains, this means creating a transparent and tamper-proof record of a product's journey from raw materials to the end consumer.

Improved traceability through blockchain can have significant benefits for quality management. It allows companies to quickly identify the source of defects or contamination if a problem arises, facilitating targeted recalls and minimizing the impact on consumers. It can also help verify the authenticity of products, combating counterfeiting, which is a major quality and safety concern in many industries (e.g., pharmaceuticals, luxury goods). Furthermore, blockchain can be used to store and share quality-related information, such as inspection certificates, test results, and compliance documentation, in a secure and auditable manner.

For example, in the food industry, blockchain can provide consumers with verifiable information about the origin, handling, and safety of food products. In manufacturing, it can track the provenance of components and ensure that they meet quality specifications. While still an emerging technology in this space, blockchain holds considerable promise for improving transparency, accountability, and trust in complex supply chains, thereby contributing to better overall quality.

This course can provide foundational knowledge in supply chain management, which is increasingly impacted by technologies like blockchain.

Global Quality Standards

In an increasingly interconnected global marketplace, adherence to internationally recognized quality standards is crucial for organizations looking to compete effectively, ensure customer satisfaction, and meet regulatory requirements. This section will delve into key global quality standards, focusing on updates to ISO 9001, industry-specific standards like IATF 16949 for the automotive sector, the cultural nuances that impact global quality practices, and the compliance challenges faced in emerging markets.

ISO 9001:2015 Updates and Beyond

ISO 9001:2015 is the current version of the world's leading Quality Management System standard. Key changes introduced in the 2015 revision included a high-level structure (Annex SL) for easier integration with other management system standards, a greater emphasis on risk-based thinking, increased leadership engagement, and a stronger focus on achieving planned results and customer satisfaction. The term "product" was expanded to "products and services" to make the standard more explicitly applicable to service industries.

The standard also introduced new clauses related to understanding the "context of the organization" and the "needs and expectations of interested parties," encouraging a broader view of factors that can impact the QMS. The requirement for a specific "management representative" was removed, with those responsibilities now falling to top management, although they can still be delegated. Preventive action was effectively replaced by the broader concept of addressing risks and opportunities. Importantly, organizations are not required to restructure their own QMS documentation to mirror the ISO 9001:2015 clause structure.

Looking ahead, ISO standards are periodically reviewed and updated to ensure they remain relevant. Minor amendments were made to ISO 9001 in 2024 to incorporate considerations related to climate change. Furthermore, the technical committee responsible for ISO 9001 (ISO/TC 176 SC2) has voted in favor of a revision, anticipated around 2025, to address evolving business environments, including changes in complexity, dynamics, and the use of new technologies. Key areas for adjustment are expected to include resilience, supply chain management, change management, sustainability, risk management, and organizational knowledge.

These courses focus on understanding and implementing ISO 9001.

Industry-Specific Standards (e.g., IATF 16949)

While ISO 9001 provides a generic framework for quality management applicable to any organization, many industries have developed specific quality standards tailored to their unique requirements and risks. These industry-specific standards often build upon the foundation of ISO 9001, adding more detailed or stringent requirements relevant to that sector. One prominent example is IATF 16949, the international quality management standard for the automotive industry. Developed by the International Automotive Task Force (IATF), it aligns with and incorporates the entirety of ISO 9001:2015 but includes supplemental automotive-specific requirements. Compliance with IATF 16949 is often a prerequisite for suppliers wishing to do business with major automotive manufacturers.

Other examples of industry-specific standards include AS9100 for the aerospace industry, ISO 13485 for medical devices, and various GMP (Good Manufacturing Practice) regulations for pharmaceuticals and food. These standards address the particular quality and safety concerns inherent in their respective sectors. Organizations operating in these industries must typically comply with both ISO 9001 (or its equivalent as a base) and the relevant industry-specific standard. This often requires a more specialized QMS and a deeper understanding of the specific regulatory and customer expectations within that field.

Cultural Considerations in Global Quality

Implementing and maintaining quality management systems in a global context requires sensitivity to cultural differences. What constitutes "quality" and how it is best achieved can be influenced by national and regional cultures. Communication styles, approaches to problem-solving, attitudes towards hierarchy and authority, and levels of employee involvement can all vary significantly across cultures, impacting the effectiveness of quality initiatives.

For instance, in some cultures, direct criticism or open disagreement in a group setting may be avoided, which can affect the dynamics of quality circles or root cause analysis sessions. In other cultures, a strong deference to authority might mean that employees are less likely to proactively identify or report quality issues. Multinational corporations need to be aware of these cultural nuances and adapt their quality management approaches accordingly. This might involve tailoring training programs, modifying communication strategies, and empowering local teams to adapt global quality policies to their specific cultural contexts.

A "one-size-fits-all" approach to global quality management is rarely effective. Successful global organizations often develop a core set of quality principles and standards that are globally consistent, while allowing for flexibility in how these are implemented at the local level. Building cross-cultural understanding and communication skills within quality teams is also crucial for navigating these complexities.

Compliance Challenges in Emerging Markets

Operating in emerging markets can present unique compliance challenges for quality management. These markets may have developing regulatory frameworks, less established infrastructure, and varying levels of technical expertise and quality awareness. This can make it more difficult to ensure consistent product quality and compliance with international standards.

Specific challenges can include:

- Supply Chain Complexity: Sourcing materials and components in emerging markets may involve dealing with a large number of smaller, less sophisticated suppliers, making supplier quality management more challenging.

- Regulatory Environment: Regulations may be less clear, subject to frequent change, or inconsistently enforced, creating uncertainty for businesses.

- Skills Gap: There may be a shortage of skilled labor with experience in modern quality management practices and technologies.

- Infrastructure Limitations: Inadequate transportation, communication, or energy infrastructure can impact production consistency and product distribution.

- Counterfeiting and Intellectual Property: Protecting products from counterfeiting and intellectual property theft can be a significant concern related to quality and brand reputation.

Overcoming these challenges requires a robust and adaptable QMS, strong local partnerships, investment in training and development, due diligence in supplier selection, and a thorough understanding of the local operating environment. Companies that successfully navigate these complexities can tap into significant growth opportunities in these dynamic markets.

Ethical Considerations in Quality Management

Ethical conduct is intrinsically linked to the principles of Quality Management. A commitment to quality inherently implies a commitment to doing the right thing for customers, employees, and society. However, quality professionals can sometimes face ethical dilemmas where business pressures may conflict with quality ideals. This section explores some key ethical considerations in Quality Management, including balancing product safety with cost, protecting whistleblowers, integrating sustainability, and ensuring social responsibility.

Product Safety vs. Cost Tradeoffs

One of the most critical ethical dilemmas in Quality Management involves balancing product safety with cost considerations. Organizations are often under pressure to reduce costs to remain competitive. However, cutting corners on design, materials, testing, or manufacturing processes to save money can compromise product safety, potentially leading to harm to consumers, reputational damage, legal liabilities, and loss of public trust.

Ethical Quality Management prioritizes safety above all else. This means designing products with safety in mind from the outset, rigorously testing them to identify and mitigate potential hazards, and ensuring that manufacturing processes consistently produce safe products. While cost is a valid business consideration, it should never come at the expense of safety. Quality professionals have an ethical obligation to advocate for safety, even if it means challenging decisions that could prioritize short-term cost savings over long-term safety and customer well-being.

This requires a strong ethical culture within the organization, where safety concerns can be raised and addressed without fear of reprisal. It also involves transparent communication with customers about product risks and proper usage. Ultimately, investing in safety is not just an ethical imperative but also a sound business strategy, as the costs of safety failures (recalls, lawsuits, brand damage) can far outweigh the costs of prevention.

This course touches upon quality and risk management in the context of supplier relationships, which can involve safety considerations.

Whistleblower Protections

Whistleblowers, individuals who report unethical or illegal activities within an organization, can play a crucial role in upholding quality and safety standards. They may bring attention to issues such as an employer cutting corners on safety protocols, falsifying quality data, or ignoring known defects. However, whistleblowers often face the risk of retaliation, including demotion, harassment, or termination.

Ethical organizations foster a culture where employees feel safe and encouraged to report concerns internally, without fear of reprisal. This includes establishing clear and accessible channels for reporting, ensuring that all reports are taken seriously and investigated thoroughly, and protecting those who come forward in good faith. Many countries have laws that provide legal protection for whistleblowers, but the effectiveness of these laws can vary, and a strong internal culture of ethical conduct is often the best defense.

For Quality Management, an environment that supports whistleblowing is vital. Quality professionals themselves may sometimes be in a position where they need to report concerns that are not being adequately addressed through normal channels. A culture of openness and accountability, where issues can be freely discussed and resolved, is essential for preventing quality failures and ensuring that ethical considerations are prioritized.

Sustainability Integration

Sustainability, which encompasses environmental, social, and economic considerations, is increasingly becoming an integral part of Quality Management. Customers, investors, and regulators are placing greater emphasis on organizations' environmental impact and social responsibility. Integrating sustainability into the QMS means considering the entire lifecycle of a product or service, from raw material extraction and manufacturing to use and disposal, with the aim of minimizing negative impacts and maximizing positive contributions.

From an environmental perspective, this can involve designing products for durability and recyclability, reducing energy consumption and waste in operations, minimizing pollution, and sourcing materials from sustainable sources. From a social perspective, it can include ensuring fair labor practices in the supply chain, promoting diversity and inclusion, and contributing positively to local communities. Economic sustainability involves ensuring the long-term viability of the business while also contributing to broader economic well-being.

Many quality principles, such as process efficiency, waste reduction (a core tenet of Lean), and continuous improvement, align naturally with sustainability goals. By broadening the definition of "quality" to include these sustainability dimensions, organizations can create more resilient and responsible businesses that meet the evolving expectations of stakeholders. Standards like ISO 14001 (Environmental Management) can be integrated with ISO 9001 to create a more comprehensive management system.

This course can provide insights into how lean principles, which emphasize waste reduction, can support sustainability goals.

Social Responsibility Reporting

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) involves a company's commitment to operate in an ethical and sustainable manner and to contribute to societal well-being. Social responsibility reporting is the practice of publicly communicating an organization's performance on CSR initiatives, including those related to quality, environmental impact, labor practices, community engagement, and ethical conduct. This transparency helps build trust with stakeholders, including customers, employees, investors, and the wider community.

Quality Management plays a key role in CSR. Ensuring product quality and safety is a fundamental social responsibility. Beyond this, quality principles like customer focus, employee involvement, and continuous improvement can be applied to enhance CSR performance. For example, focusing on employee well-being and development (an aspect of social responsibility) can lead to a more engaged and quality-conscious workforce. Similarly, ensuring ethical sourcing and fair labor practices in the supply chain is both a quality and a CSR concern.

Many organizations now publish annual CSR or sustainability reports, often using frameworks like the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) standards. These reports provide data and narratives on the company's CSR goals, activities, and performance. Accurate and transparent reporting on quality-related CSR aspects, such as product safety records, customer satisfaction levels, and environmental compliance, demonstrates a commitment to accountability and continuous improvement in these critical areas.

Frequently Asked Questions

This section addresses some common questions that individuals, especially those new to the field or considering a career change, may have about Quality Management. The answers aim to provide concise and actionable information to help you better understand the profession and its requirements.

What are the essential skills for a successful career in Quality Management?

A successful career in Quality Management requires a blend of technical and soft skills. Strong analytical and problem-solving abilities are crucial for identifying issues, analyzing data, and developing effective solutions. Attention to detail is paramount, as quality professionals must ensure that products, services, and processes meet precise standards. Excellent communication skills, both written and verbal, are necessary for documenting procedures, reporting findings, and collaborating with diverse teams and stakeholders.

Technical skills often include a good understanding of statistical methods, quality control tools (like SPC, FMEA, Fishbone diagrams), and relevant quality standards (like ISO 9001). Familiarity with quality management software and data analysis tools can also be very beneficial. Project management skills are important for leading improvement initiatives.

On the soft skills side, leadership, teamwork, and the ability to influence others are key, especially for management roles. Adaptability and a commitment to continuous learning are also vital, as the field of quality is constantly evolving with new technologies and methodologies. A proactive and customer-focused mindset is fundamental to driving a culture of quality.

Is a certification valuable even if I don't have an engineering degree?

Yes, certifications in Quality Management can be highly valuable even without an engineering degree. While an engineering background can be beneficial, especially in manufacturing or technical industries, many quality roles and principles are applicable across diverse sectors, including services, healthcare, and software. Quality Management is a multidisciplinary field, and individuals from various academic backgrounds (such as business, science, or even liberal arts with relevant experience) can build successful careers.

Certifications like ASQ's Certified Manager of Quality/Organizational Excellence (CMQ/OE), Certified Quality Auditor (CQA), or various Six Sigma belts demonstrate a specific body of knowledge and competence in quality principles and practices. They can significantly enhance your credibility, marketability, and earning potential, regardless of your undergraduate major. Many certifications focus on methodologies and tools that are transferable across industries. Employers often value the demonstrated commitment to the quality profession that a certification represents.

If you lack an engineering degree but are interested in Quality Management, gaining practical experience, taking relevant courses (many of which are available online through platforms like OpenCourser), and then pursuing certifications can be an excellent strategy for career entry or advancement.

Are there remote work opportunities in Quality Management?

The availability of remote work opportunities in Quality Management has been growing, particularly with advancements in technology and shifts in work culture. However, the extent of remote work often depends on the specific role and industry. Roles that are heavily involved in documentation, data analysis, QMS development, auditing (especially desk audits or remote audits), training, and consulting can often be performed remotely, at least partially.

For example, a Quality Management System Specialist developing documentation or a Quality Data Analyst might work effectively from a remote location. Some aspects of auditing can also be done remotely by reviewing documents and records online and conducting interviews via video conferencing. However, roles that require hands-on inspection of physical products, direct observation of manufacturing processes, or on-site troubleshooting are less likely to be fully remote. This includes many Quality Inspector, Quality Technician, and some Quality Engineer positions in manufacturing environments.

The trend towards digitalization in quality, including the use of cloud-based QMS software and remote collaboration tools, is likely to expand remote work possibilities further. Job seekers interested in remote Quality Management roles should look for positions that emphasize skills in data analysis, system management, and virtual communication, and in industries that are more amenable to remote operations.

How is automation impacting jobs in the quality sector?

Automation is bringing significant changes to jobs in the quality sector, but it's more of a transformation than a simple replacement of human roles. Automated Quality Control systems, as discussed earlier, can perform many routine inspection and testing tasks faster, more consistently, and sometimes more accurately than humans. This means that the demand for purely manual inspection roles may decrease over time.

However, automation also creates new opportunities and shifts the focus of quality professionals towards higher-value activities. There will be a need for individuals who can design, implement, maintain, and manage these automated systems. Quality professionals will increasingly focus on analyzing the vast amounts of data generated by automated systems to identify trends, predict issues, and drive process improvements. Skills in data science, AI, and robotics will become more valuable in the quality field.

Furthermore, human oversight, critical thinking, problem-solving, and the ability to manage complex quality systems remain essential. Automation can free up quality personnel from repetitive tasks, allowing them to concentrate on strategic initiatives, root cause analysis of complex problems, supplier quality development, customer interaction, and fostering a culture of quality. So, while some job tasks will change, the overall importance of skilled quality professionals is likely to remain high, albeit with an evolving skill set.

What does a typical career progression in Quality Management look like?

A typical career progression in Quality Management often starts with entry-level roles focused on operational tasks and gradually moves towards positions with greater responsibility, strategic input, and leadership. A common pathway might begin with a role like Quality Inspector or Quality Technician, gaining hands-on experience with quality control processes, inspection techniques, and data collection.

With experience and perhaps further education or certification, one might progress to a Quality Engineer role. Quality Engineers are often involved in designing quality systems, analyzing data, solving problems, and leading improvement projects. From there, individuals can move into Quality Management positions, such as Quality Supervisor or Quality Manager, overseeing quality functions, managing teams, and ensuring compliance with standards. Average salaries for Quality Managers can be around $76,000, with ranges potentially extending from $55,000 to $80,000 or higher depending on factors like industry and location.

Further advancement can lead to senior leadership roles like Director of Quality or VP of Quality, where individuals are responsible for the overall quality strategy and performance of the organization. Alternatively, some quality professionals may choose to specialize in areas like auditing (becoming a Lead Auditor), Six Sigma (as a Master Black Belt), or consulting. The path can vary based on industry, company size, and individual career goals. Continuous learning and obtaining relevant certifications often play a key role in facilitating career progression.

What are the global demand trends for quality management specialists?

The global demand for quality management specialists remains robust and is expected to grow, driven by several factors. Increasing customer expectations for high-quality products and services, coupled with more stringent regulatory requirements across many industries, necessitate a strong focus on quality. Globalization and complex supply chains also increase the need for professionals who can manage quality across diverse operations and ensure consistency.

Industries such as manufacturing (especially automotive, aerospace, electronics, and medical devices), healthcare, pharmaceuticals, food and beverage, and software development consistently seek quality professionals. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), overall employment of industrial production managers, a category that can include quality management roles, is projected to show little or no change from 2022 to 2032. However, specific niches within quality may see different growth rates. For instance, roles requiring expertise in data analytics, automation, and emerging technologies related to quality are likely to be in higher demand. The BLS also projects growth for general and operations managers, some of whom may have quality-related responsibilities.

Emerging markets are also contributing to the demand as they industrialize and seek to compete on quality in the global marketplace. The emphasis on continuous improvement, risk management, and operational excellence in modern business practices ensures that quality management skills will continue to be valuable. Professionals who stay updated with the latest methodologies, technologies, and industry standards will be well-positioned to meet this ongoing demand.

Further Resources and Useful Links

To continue your exploration of Quality Management, the following resources may be helpful:

- The American Society for Quality (ASQ) is a global community of people passionate about quality, who use the tools, their ideas and expertise to make our world work better. ASQ provides training, certifications, and a wealth of resources on quality management.

- The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) develops and publishes international standards, including ISO 9001. Their website offers detailed information about these standards.

- For those looking to find online courses to build their knowledge, OpenCourser offers a vast catalog of courses from various providers. You can browse categories such as Project Management and Industrial Engineering for relevant programs.

- The OpenCourser Learner's Guide provides valuable tips on how to make the most of online learning, create a study plan, and stay motivated.